Miami Vice (film)

| Miami Vice | |

|---|---|

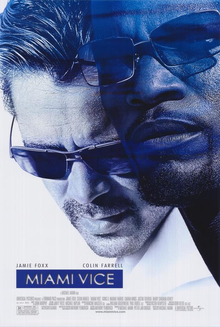

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Mann |

| Screenplay by | Michael Mann |

| Based on | Miami Vice by Anthony Yerkovich |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dion Beebe |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | John Murphy |

Production company | Forward Pass |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 132 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $135 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $164.2 million[2] |

Miami Vice is a 2006 action thriller film written and directed by Michael Mann. The film is an adaptation of the 1980s television series of the same name, on which Mann was an executive producer.

The film stars Colin Farrell as Crockett and Jamie Foxx as Tubbs, as well as Gong Li, Justin Theroux, Naomie Harris, Ciarán Hinds, Barry Shabaka Henley, Luis Tosar, and John Ortiz, with supporting roles by Isaach De Bankolé, Eddie Marsan and others. The film follows Miami-Dade Police Department (MDPD) detectives James "Sonny" Crockett and Ricardo "Rico" Tubbs, who go undercover to fight drug trafficking operations.

Miami Vice premiered in Westwood, California, on July 20, 2006, prior to its wide release on July 28, 2006, and was also released in Germany on August 24, 2006. The film received mixed reviews, praise went to Mann's directing and visual style while the storyline and characterization received some criticism. It grossed $164.2 million worldwide on a reported $135 million budget.

Plot[]

While working an undercover prostitute sting operation in a nightclub to arrest a pimp named Neptune, Miami-Dade Police detectives James "Sonny" Crockett and Ricardo "Rico" Tubbs receive a frantic phone call from their former informant Alonzo Stevens. Stevens reveals that he's leaving town, and, believing his wife Leonetta to be in immediate danger, asks Rico to check on her. Crockett learns that Stevens was working as an informant for the FBI but has been compromised.

Crockett and Tubbs quickly contact FBI Special Agent in Charge John Fujima and warn him about Stevens' safety. Tracking down Stevens through a vehicle transponder and aerial surveillance, Crockett and Tubbs stop him along I-95. Stevens reveals that a Colombian cartel had become aware that Russian undercovers (now dead) were working with the FBI, and had threatened to murder Leonetta via a C-4 necklace bomb if he didn't confess. Rico, learning of Leonetta's death by telephone call, tells Alonzo that he doesn't have to go home. Hearing this, the grief-stricken Stevens commits suicide by walking in front of an oncoming semi truck.

En route to the murder scene, Sonny and Rico receive a call from Lt. Martin Castillo and are instructed to stay away. He tells them to meet him downtown, where they are introduced in person to John Fujima, head of the Florida Joint Inter-Agency Task Force between the FBI, the DEA, and ICE. Crockett and Tubbs berate Fujima for the errors committed and inquire as to why the MDPD wasn't involved. Fujima reveals that the Colombian group part of the A.U.C. is highly sophisticated and run by José Yero, initially thought to be the cartel's leader. Fujima enlists Crockett and Tubbs, making them Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force deputies, to help, and they continue the investigation by looking into go-fast boats coming from the Caribbean, delivering loads of narcotics from the Colombians. They then use their Miami informant contacts to set up a meet and greet with the cartel.

Posing as drug smugglers, Sonny and Rico offer their services to Yero, the cartel's security and intelligence man. After a high tension meeting, they pass screening and are introduced to Arcángel de Jesús Montoya, transnational drug trafficking kingpin. In the course of their investigation, Crockett and Tubbs learn that the cartel is using the Aryan Brotherhood to distribute drugs, and is supplying them with state-of-the-art weaponry (which they had used to kill the Russian undercovers). Meanwhile, Crockett tries to gather further evidence from Montoya's financial adviser and lover, Isabella, but ends up starting a secret romance while on a trip with her by speedboat to Cuba. Tubbs begins to fear for the team's safety with Crockett's fling. Those fears are soon realized as Trudy, the unit's intelligence agent and Rico's girlfriend, is kidnapped by the Aryan Brotherhood by Yero's order, who never trusted Crockett and Tubbs. The Aryan Brotherhood demand for Crockett and Tubbs to deliver the cartel's load directly to them. With Lt. Castillo's help, the unit triangulates Trudy's location to a mobile home in a trailer park and perform a rescue, but she is critically injured when Tubbs fails to evacuate her before a bomb is remotely detonated by Yero. Soon afterwards, Yero reveals Isabella's betrayal to Montoya and captures her. In the showdown, Crockett and Tubbs face off against Yero, his men, and the Aryan Brotherhood at the port of Miami.

During the firefight, Crockett begins to call in backup. When Isabella sees his police shield and radio, she realizes that he's a cop. Betrayed, Isabella wrestles with Crockett until he subdues her. Tubbs guns down Yero as he attempts to shoot his way to safety. After the gunfight, Crockett takes Isabella to a police safehouse and insists she will have to leave without him. Isabella tells him "time is luck," holding out hope the fling can continue, but he tells her they "have run out of time."

Crockett arranges for Isabella to leave the country and return home in Cuba, thus avoiding arrest. Meanwhile, Tubbs is keeping watch on Trudy in hospital as she begins to awaken from her coma.

Cast[]

| Character | Original series | 2006 movie |

|---|---|---|

| Detective James 'Sonny' Crockett | Don Johnson | Colin Farrell |

| Detective Ricardo 'Rico' Tubbs | Philip Michael Thomas | Jamie Foxx |

| Detective Trudy Joplin | Olivia Brown | Naomie Harris |

| Detective Gina Calabrese | Saundra Santiago | Elizabeth Rodriguez |

| Detective Stan Switek | Michael Talbott | Domenick Lombardozzi |

| Detective Larry Zito | John Diehl | Justin Theroux |

| Lieutenant Martin Castillo | Edward James Olmos | Barry Shabaka Henley |

Newly created characters[]

- Gong Li as Isabella

- Luis Tosar as Arcángel de Jesús Montoya

- John Ortiz as José Yero

- Ciarán Hinds as FBI Agent John Fujima

- Isaach De Bankolé as 'Neptune'

- John Hawkes as Alonzo Stevens

- Tom Towles as Coleman

- Eddie Marsan as Nicholas

Production[]

Development[]

Jamie Foxx brought up the idea of a Miami Vice film to Michael Mann during a party for Ali. This led Michael Mann to revisit the series he helped create.[4]

Like Collateral, which also starred Foxx, most of the film was shot with the Thomson Viper Filmstream Camera, while Super 35 was used for high-speed and underwater shots. Cinematographer Dion Beebe was also Collateral's cinematographer.[5]

The suits that Jamie Foxx wore in the film were designed by noted fashion designer Ozwald Boateng. He had worked with Foxx in the past and caught Mann's eye, who then asked him to work on the film.[6] Michael Kaplan was responsible for the costume design overall.

Filming[]

The film was shot on location in the Caribbean, Uruguay, Paraguay (Ciudad del Este),[7] and South Florida. Uruguay locations included the seaside resort Atlántida standing in for Havana,[8] the old building of the Carrasco International Airport, and the Rambla waterfront avenue and the Old City in Montevideo. Seven days of filming were lost to hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma.[9] The delays led to a budget of what some insiders claimed to be over $150 million, though Universal Pictures says it cost $135 million.[3] Several crew members criticized Mann's decisions during production, which featured sudden script changes, filming in unsafe weather conditions, and choosing locations that "even the police avoid, drafting gang members to work as security".[3]

Foxx was also characterized as unpleasant to work with. He refused to fly commercially, forcing Universal to give him a private jet. He also wouldn't participate in scenes on boats or planes. After gunshots were fired on set in the Dominican Republic on October 24, 2005, Foxx packed up and refused to return; this forced Mann to re-write the film's ending, which some crew members characterized as less dramatic than the original.[3] Foxx, who won an Academy Award after signing to do Miami Vice, was also reputed to complain about co-star Farrell's larger salary, which Foxx felt didn't reflect his new status as an Oscar winner; consequently, reports Slate: "Foxx got a big raise while Farrell took a bit of a cut." Slate also reported that Foxx demanded top billing after winning an Oscar.[3]

Mann wanted a film that was as real as it was stylish and even put Farrell in jeopardy by bringing him along (with real FBI drug squads) to drug busts so the actor could build up the character of Crockett even more. It was later revealed that Mann faked these busts.[10]

Sal Magluta, the drug trafficker identified by Tubbs as running go-fast boats in the film's opening scenes, is in fact one of Miami's real-life reputed "Cocaine Cowboys"[11] and is currently serving a life sentence for money laundering.[12]

The first teaser trailer to appear for the film featured the Linkin Park and Jay-Z song "Numb/Encore". This trailer was attached to the release of King Kong in theaters. For several months before its release, the official web site hosted the first teaser trailer for download as a High-Definition WMV download.

Music[]

The original Miami Vice television series composer, Jan Hammer was not asked to compose the soundtrack; Michael Mann did not want to use the theme song.[13] Furthermore, Mann did not want any association with the TV series. Fans of the series e-mailed Universal thousands of letters to include the theme, but ultimately Mann said no.[13] As Hammer put it: "I was completely surprised they didn't have a remake of it. I think it's a matter of being too cool for school."[13]

Phil Collins' famous hit "In the Air Tonight", which was featured in the television series' pilot episode, is featured in the original film as a cover done by Miami-based rock band Nonpoint[14] during the closing credits and on the soundtrack. Mann's "Director's Edit" released on DVD places the song in the film just prior to the climactic gun battle as suggested by members of the production crew during post-production.[15]

- Nonpoint - "In the Air Tonight"

- Moby featuring Patti LaBelle - "One of These Mornings"

- Mogwai - "We're No Here"

- Nina Simone - "Sinnerman (Felix da Housecat's Heavenly House Mix)"

- Mogwai - "Auto Rock"

- Manzanita - "Arranca"

- India.Arie - "Ready for Love"

- Goldfrapp - "Strict Machine"

- Emilio Estefan - "Pennies in My Pocket"

- King Britt - "New World in My View"

- Blue Foundation - "Sweep"

- Moby - "Anthem"

- Freaky Chakra - "Blacklight Fantasy"

- John Murphy - "Mercado Nuevo"

- John Murphy - "Who Are You"

- King Britt & Tim Motzer - "Ramblas"

- Klaus Badelt & Mark Batson - "A-500"

The RZA was supposed to contribute to the film's score but dropped out for unknown reasons.[16][17] Atlanta based producers Organized Noize were brought in to take RZA's place instead.

The music included on the soundtrack has several differences from what was featured in the film:[citation needed]

- Of the first four songs featured in the film's first sequence in The Mansion nightclub, three are on the soundtrack and Nina Simone's "Sinnerman" is the only song to be featured in its original form. Jay-Z and Linkin Park's "Numb/Encore" is not found on the soundtrack despite being featured in both of the film's trailers and being the first song in the film. Furthermore, the version of Goldfrapp's "Strict Machine" is the We Are Glitter remix of the song, and both it and Freaky Chakra's "Blacklight Fantasy" are edits from Sasha's mix album Fundacion NYC. Neither version appears on the soundtrack.

- Clips of two Audioslave songs, "Wide Awake" and "Shape of Things to Come", are featured in the film, but the songs do not appear on the soundtrack. This was possibly because the two songs were brand new and were set to be featured on Audioslave's new album Revelations, which had a release date close to the film.

- The version of Moby's "Anthem" on the soundtrack does not appear in the film. Instead, prominent placement is given to Moby's "Cinematic Version" of the song.

- King Britt's "New World in My View" is featured in the film but is missing the spoken-word lyrics of Sister Gertrude. The song plays instrumentally in the background at one point in the film.

Release[]

Theatrical run[]

Miami Vice opened at No. 1 in the United States, knocking Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest out of the number one position at the box office that weekend, after Pirates led the box office for almost a full month.[18] In its opening weekend, the film grossed over $25.7 million at 3,021 theaters nationwide, with an average gross of $8,515 per theater.[19] The film would go on to earn $63.5 million in Canada and the US.[19] Miami Vice would fare better internationally. The film aired in 77 countries overseas, grossing $100,344,039 in its international run.[20] Overall the film grossed $164 million worldwide against a reported $135 million budget.[19]

Home release[]

Miami Vice was released to DVD on December 12, 2006. It contained many extra features the theatrical version did not include, as well as an extended cut of the film itself, titled "the Director's Cut, with a running time of 140 minutes.[21] It was one of the first HD DVD/DVD combo discs to be released by Universal Studios and one of the best-selling DVDs of 2006.[22] It debuted in third place (behind Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest and Superman Returns) and managed to sell over a million copies in its first week alone.[23] As of February 11, 2007, Miami Vice had grossed over $36.45 million in rentals.[24]

On August 26, 2008, Universal Studios released the "Unrated Director's Edition" of Miami Vice on Blu-ray.[25][26]

Critical reception[]

On the film-review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Miami Vice holds a 46% approval rating based on 224 reviews, with an average rating of 5.6/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Miami Vice is beautifully shot but the lead characters lack the charisma of their TV series counterparts, and the underdeveloped story is well below the standards of Michael Mann's better films."[27] On Metacritic it holds a 65, representing "generally favorable reviews".[28]

It received positive notices from major publications including Rolling Stone,[29] Empire,[30] Variety,[31] Newsweek,[32] New York,[33] The Village Voice,[34] The Boston Globe,[35] Entertainment Weekly,[36] and film critic Richard Roeper on the television program Ebert & Roeper.[37] The New York Times critic Manohla Dargis declared it "glorious entertainment" in her year-end wrap-up and praised its innovative use of digital photography.[38]

The film received negative reviews from The Washington Post[39] and the Los Angeles Times, focusing in part on comparisons with the 1980s series and on the plot.[40]

It was included in the top ten of 2006 by Scott Foundas (LA Weekly) at #7, and by Manohla Dargis at #8.[41] Additionally, in November 2009, the critics of Time Out New York chose Miami Vice as #35 of the fifty best films of the decade, saying:

Writer-director Michael Mann brilliantly rethinks the seminal 1980s TV series on which he made his name. The hi-def videography gives a tactile, scorching sense of the characters' surroundings, and Colin Farrell and Gong Li's doomed love affair bears the full tragic brunt of Mann's mesmerizing on-the-fly narrative.[42]

Miami Vice was named the 95th best action film of all time in a 2014 Time Out poll of film critics, directors, actors and stunt actors.[43][44]

In 2016, critic Steven Hyden wrote that Miami Vice had developed "a burgeoning reputation as a cult favorite, especially among younger critics and filmmakers who consider it a touchstone in their love of movies." He wrote that the focus on "gloomy atmosphere and visual sensation" over plot and dialogue (much of which, he wrote, was "incomprehensible") made the film a visual meditation on "failure and futility" that was "one of the most expensive art films ever made."[45] In Senses of Cinema, French director and critic praised the film's digital aesthetic, extreme pace, and philosophical undertones; he called Miami Vice "a radical work that does not give up its author's formal and stylistic ambitions" and "an inspired synthesis of impressionism and hyper-realism," and said the film "has also just laid the foundations for a new order of action films."[46]

Director Harmony Korine cited Miami Vice as a major influence on his 2012 film Spring Breakers. "The reason I love [Mann's] movies, and that movie in particular," Korine said, "is I could feel the place. When I watch that film, I don't even pay attention to what they're saying or the storyline. I love the colors, I love the texture."[47]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Miami Vice (2006)". American Film Institute. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Miami Vice (2006)". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Fleeing the Scene". Slate. July 13, 2006.

- ^ "Black Entertainment | Black News | Urban News |Hip Hop News". EURweb.com. July 28, 2006. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ "Miami Vice in HD". Digitalcontentproducer.com. May 23, 2006. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ "Eurweb". Eurweb.com. June 19, 2006. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- ^ "Shooting Locations for Vice". Atlantis International. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011.

- ^ "Shooting locations in Uruguay". Movieshootinglocations.uruguayphotos.eu. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ Snyder, Gabriel (January 15, 2006). "'Vice' feels the squeeze: Timing a little off for Mann's latest project". Variety. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ See Miami Vice DVD featurette

- ^ Weaver, Jay (May 5, 2012). "Miami woman freed from life sentence in 'Willie and Sal' drug-murder hit". Miami Herald. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "Reputed 'cocaine cowboy' makes prison deal: Sentencing in July will be for money laundering conspiracy and $1-million in restitution". St. Petersburg State Times. Associated Press. June 17, 2003. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Friedman, Roger (July 25, 2006). "Miami Vice Theme: Axed, but Alive". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (July 26, 2006). "'Miami Vice' makes series of changes". USA Today. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Flerman, Daniel (July 21, 2006). "Miami Heat". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "The United States Chess Federation - Interview with RZA". Main.uschess.org. October 9, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- ^ "Miami Vice". ignore Magazine. 2009. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Klatell, James M. (July 30, 2006). "'Miami Vice' Sinks 'Pirates'". CBS News. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Miami Vice (2006)". boxofficemojo. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ "Miami Vice Foreign Totals". boxofficemojo. December 16, 2007. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Williams, Ben (September 3, 2008). "Miami Vice Blu-ray Review". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ "Universal Planning More Than 100 HD DVDs". ComingSoon.net. January 25, 2007. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ C.S. Strowbridge (December 16, 2006). "10 Million People Purchase Pirate DVDs This Week". The Numbers News. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ "Miami Vice (2006) - DVD / Home Video Rentals". BoxOfficeMojo. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Gibbs, Tom (August 25, 2008). "Miami Vice, Blu-ray (2008, Original release 2006)". Audiophile Audition. Archived from the original on July 24, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Miami Vice (Unrated Director's Edition) Blu-ray (2006)". Amazon.com. 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Miami Vice (2006)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Miami Vice (2006): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Travers, Peter (July 20, 2006). "Miami Vice: Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Braund, Simon. "Review of Miami Vice". Empire Reviews Central. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (July 23, 2006). "Miami Vice". Variety. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Ansen, David (July 31, 2006). "Lukewarm Waters". Newsweek Entertainment. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Edelstein, David (July 24, 2006). "Sea, Sun, and Hungry Sex". New York. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (July 18, 2006). "Undercover of the Night". The Village Voice. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Morris, Wesley (July 28, 2006). "'Vice' Grip". The Boston Globe. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (July 26, 2006). "Miami Vice (2006)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ "Miami Vice Review". At the Movies. 2006. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (December 24, 2006). "Not for the Faint of Heart or Lazy of Thought". The New York Times. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Hunter, Stephen (July 28, 2006). "'Miami Vice': Way Cool Then, Now Not So Hot". Washington Post. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (July 28, 2006). "'Miami Vice'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ "Metacritic 2008 Film Critic Top Ten Lists 2006". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 3, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2009.

- ^ "The TONY top 50 movies of the decade". Time Out New York. No. 739. November 26 – December 2, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ "The 100 best action movies". Time Out. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "The 100 best action movies: 100-91". Time Out. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (July 21, 2016). "Why It Took 10 Years For Michael Mann's 'Miami Vice' To Get Its Due". Uproxx.

- ^ Thoret, Jean-Baptiste (February 2007). Translated by Shafto, Sally. "Gravity of the Flux: Michael Mann's Miami Vice". Senses of Cinema (42).

- ^ Lim, Dennis (September 7, 2012). "Venice Film Festival: James Franco and Harmony Korine on 'Spring Breakers'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Miami Vice (film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Miami Vice. |

- Official website

- Miami Vice at IMDb

- Miami Vice at AllMovie

- Miami Vice at Box Office Mojo

- Miami Vice script

- Miami Vice soundtrack questions, answers and other information

- Thomson Viper Camera

- Miami Vice 2006 Movie Production Notes

- Articles

- Miami Beach USA Miami Vice: Fashion Trend-Setter Again?

- Entertainment Weekly's cover story on the making of the film

- Interview: Michael Mann & The Cast Miami Vice

- Senses of Cinema essay

- 2006 films

- English-language films

- Miami Vice

- 2006 action thriller films

- 2006 crime drama films

- 2006 crime thriller films

- 2000s buddy cop films

- 2000s crime action films

- American action thriller films

- American buddy cop films

- American buddy drama films

- American crime action films

- American crime drama films

- American crime thriller films

- American films

- American neo-noir films

- American police detective films

- German action thriller films

- German crime action films

- German crime drama films

- German crime thriller films

- German films

- German neo-noir films

- Fictional portrayals of the Miami-Dade Police Department

- Films about Colombian drug cartels

- Films about the Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Films about organized crime in the United States

- Films based on television series

- Films directed by Michael Mann

- Films scored by John Murphy (composer)

- Films set in Colombia

- Films set in Havana

- Films set in Miami

- Films shot in Brazil

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in the Dominican Republic

- Films shot in Havana

- Films shot in Miami

- Films shot in Paraguay

- Films shot in Uruguay