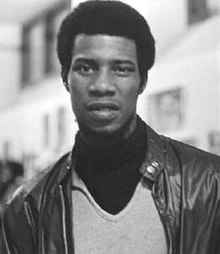

Michael Tabor (activist)

Michael Aloysius Tabor | |

|---|---|

Michael Aloysius Tabor | |

| Born | Michael Aloysius Tabor December 13, 1946 Harlem, New York, US |

| Died | October 17, 2010 (aged 63) |

| Other names | Cetewayo |

| Occupation | Activist |

| Years active | 1970–72 |

| Organization | Black Panther Party |

| Spouse(s) | Connie Matthews(?–1972) Priscilla Matanda(?–2010) |

| Children | 4 |

Michael Aloysius Tabor (December 13, 1946 – October 17, 2010) was an American member of the Black Panther Party who was charged and tried as part of an alleged conspiracy to bomb public buildings in New York City and kill members of the New York Police Department. Four months into the trial Tabor and another defendant fled to Algeria. Despite his ultimate acquittal on all charges, Tabor remained in exile in Africa until his death, never returning to the United States.

Tabor was born on December 13, 1946, in Harlem and joined the Black Panther Party while in his teens. He took the name Cetewayo, a 19th century Zulu king.[1] In 1969, he authored the pamphlet Capitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide.[2] In 1970, Tabor and 12 other members of the Black Panthers were charged for allegedly plotting to kill police officers and to plant bombs in New York City commercial and public buildings, including the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx. Support for the prosecution's case came from undercover officers who claimed that the defendants had developed plans for a series of bombings and had conducted classes to instruct those participating in the plot how to construct explosive devices.[3]

Together with fellow defendant Richard Moore, Tabor failed to appear at their trial in February 1971, forfeited $150,000 in bail and were declared fugitives. Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton called Moore and Tabor "enemies of the people" for evading justice while on trial and putting the other defendants and the party at risk.[4] Connie Matthews, Newton's former secretary and Tabor's wife, also left the country and was said to have taken valuable records with her.[4] The two finally surfaced in Algeria the following month together with Eldridge Cleaver.[5]

The New York Times published a lengthy letter from Moore on the day before the verdicts were read explaining that they had fled the U.S. because they feared that their lives were at risk.[6] On May 13, 1971, after an eight-month-long trial, the jury in New York Supreme Court in Manhattan delivered an acquittal on all 156 counts.[7] In a statement issued from Algiers, Tabor stated that the trial represented "an attempted railroad and that the defendants' rights were flagrantly violated" and said that he was "overjoyed that the brothers are free".[3]

Algeria expelled Tabor and he and Matthews moved to Zambia in 1972, where Mike hosted a drive-time radio show on 105.1, "The Happy World of 5 FM" in Lusaka Zambia, and was known for his rhyming introduction in a deep baritone, "Rhyming the time at the sound of the chime" at which point he would ring a small bell that he always kept by his side. Mike told others in Lusaka that he had been a Communications Director for the Black Panthers, and that he came to Zambia in the 70s because it was the seat of the African National Congress or ANC. Tabor wrote about politics. Despite repeated requests, Tabor refused to return to the United States. He died at age 63 in Lusaka, Zambia, on October 17, 2010, due to complications of multiple strokes. He was survived by his second wife, Priscilla Matanda, as well as by a daughter and three sons.[3]

References[]

- ^ http://www.abujacity.com/abuja_and_beyond/2010/10/michael-tabor-former-panther-dies.html

- ^ "Capitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hevesi, Dennis. "Michael Tabor, Black Panther Who Fled to Algeria, Dies at 63", The New York Times, October 23, 2010. Accessed October 27, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asbury, Edith Evans. "Newton Denounces 2 Missing Panthers", The New York Times, February 10, 1971. Accessed October 27, 2010.

- ^ Staff. "RADICALS: Destroying the Panther Myth", Time, March 22, 1971. Accessed October 27, 2010.

- ^ Moore, Richard. "A Black Panther Speaks", The New York Times, May 12, 1971. Accessed October 27, 2010.

- ^ Asbury, Edith Evans. "Black Panther Party Members Freed After Being Cleared of Charges; 13 PANTHERS HERE FOUND NOT GUILTY ON ALL 12 COUNTS", The New York Times, May 14, 1971. Accessed October 27, 2010.

- 1946 births

- 2010 deaths

- Members of the Black Panther Party

- People from Harlem

- American emigrants to Zambia

- American expatriates in Algeria

- Activists from New York City