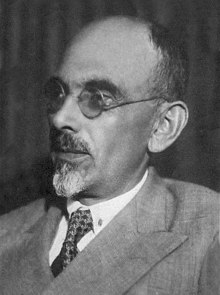

Mikheil Javakhishvili

Mikheil Javakhishvili | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | მიხეილ ჯავახიშვილი |

| Born | 8 November 1880 Tserakvi, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 30 September 1937 (aged 56) Tbilisi, Georgian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | writer, novelist |

| Language | Georgian |

| Nationality | Georgian |

| Genre | Critical Realism |

| Notable works |

|

Mikheil Javakhishvili (Georgian: მიხეილ ჯავახიშვილი; birth surname: Adamashvili ადამაშვილი) (08 November 1880 – 30 September 1937) was a Georgian novelist who is regarded as one of the top twentieth-century Georgian writers. His first story appeared in 1903, but then the writer lapsed into a long pause before returning to writing in the early 1920s. His recalcitrance to the Soviet ideological pressure cost him life: he was executed during the Great Purge and his writings were banned for nearly twenty years. In the words of the modern British scholar of Russian and Georgian literature, Donald Rayfield, "his vivid story-telling, straight in medias res, his buoyant humour, subtle irony, and moral courage merit comparison with those of Stendhal, Guy de Maupassant, and Émile Zola. In modern Georgian prose only Konstantine Gamsakhurdia could aspire to the same international level."[1]

Early life and career[]

He was born as Mikheil Adamashvili in the village of Tserakvi in what is now the Kvemo Kartli region, Georgia (then part of Imperial Russia). The mishmash with his real family name was later explained by writer himself. According to him, his grandparent, born as Javakhishvili (noble family from the province Kartli) killed a man, therefore had to flee to Kakheti where he took a new name Toklikishvili. Mikheil's grandfather Adam returned in Kartli. His son Saba was registered as Adamashvili. Mikheil was also wearing this name in his youth but later he returned the family name of ancestors-Javakhishvili. He enrolled into the Yalta College of Horticulture and Viticulture, but a family tragedy forced him to abandon his studies: robbers killed his mother and sister, and his father died shortly thereafter. Returning to Georgia in 1901, he worked at a copper smeltery in Kakheti. His first story was published in 1903 under the penname of Javakhishvili, followed by a series of journalistic articles critical of the Russian authorities. In 1906, the Tsarist political repressions forced him to retire to France, where he studied art and political economy at the University of Paris. After the extensive travels to Switzerland, Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, the United States, Germany and Turkey from 1908 to 1909, he clandestinely returned to his homeland only to be arrested and exiled from Georgia in 1910.[2] He returned in 1917 and, after almost fifteen years of pause, resumed writing. In 1921, he joined the National Democratic Party of Georgia and was in opposition to the Soviet government established in Georgia the same year. In 1923, during the Bolshevik crackdown on the party, Javakhishvili was arrested and sentenced to death, but was exonerated through the mediation of the Georgian Union of Writers and released after six months of imprisonment. Javakhishvili's reconciliation with the Soviet regime was only superficial and his relations with the new authorities remained uneasy.

Best works[]

Javakhishvili skillfully incorporated folk phraseology into the normalized narrative language. In his best writings, the novelist combines the devastating realism and characteristic humorous touches with underlying pessimism and anarchy to contrast country and city life, tsarist and Soviet times. His plots, sometimes overtly rebellious, violent, and sexually passionate, intersect traditional taboos and belie any reconciliation with the new world and have a common ground: the rise of the Georgian kulak, the life of the Georgian aristocratic intellectual and dilettante, and the impact on them both of the revolutionary upheaval of 1917 and the Bolshevik takeover of 1921.

In his most typical and influential novella, Jaqo's Dispossessed (ჯაყოს ხიზნები; Jakos Khiznebi), first published in 1924, Javakhishvili contrasts the swashbuckling, grasping, and swindler Jaqo with his victim, Prince Teimuraz Khevistavi, the amiable intellectual and ineffectual philanthropist whom his trustee, Jaqo, robs of his fortune, his beautiful and beloved wife Margo, and even of his sanity. In the person of Teimuraz, we follow the decline and fall of the old nobility, the disillusionment in the revolution and demoralization following the fall of a short-lived independent Georgia. Another major work, the satirical Kvachi Kvachantiradze (კვაჭი კვაჭანტირაძე; 1924), was dramatized in 1927 for Sandro Akhmeteli's Rustaveli Theater, but the project was aborted when the leading pro-Bolshevik critics denounced it as pornography (the play has since been lost). In his 1926 novel The White Collar (თეთრი საყელო), Javakhishvili describes the fate of the freedom-loving and stoical Georgian mountaineers – Khevsurs – in the new Soviet reality. The Tbilisian Elizbar, irritated to despise by his highly sexed, but stupid cosmopolitan wife, Tsutskia, withdraws into the Khevsuretian highlands and while prospecting for copper falls in love and marries a strongly traditional but loving and vivacious Khevsur clanswoman Khatuna. Although welcomed and befriended by the local mountainous community, Elizbar, longing to return to the city's life (symbolized in the story by The White Collar), brings Khatuna to Tbilisi and abandons his highlander friends and in-laws in the face of a forthcoming disaster preceded by the Khevsur armed resistance to the Soviets.[3]

The crowning merit of Javakhishvili's work – the novel Arsena of Marabda (არსენა მარაბდელი) – was composed between 1933 and 1936. The writer spent years on research and rewriting a Russian as well as a Georgian version of the novel. The plot is based on the life of a real historical figure, the brigand Arsena Odzelashvili, who is also a favorite hero of Georgian folklore. Javakhishvili focuses on the tragic necessity that makes the chivalrous peasant Arsena to degenerate into the typical 19th-century bandit. Although the story of an outlaw fighting against the gentry was considered "ideologically correct", the "left" critics were suspicious of Javakhishvili's recognizable parallels between Imperial Russia and the Soviet state. Javakhishvili put many of his thoughts into Arsena's mouth. One example is his famous phrase: "Russia is galloping after Europe and the bleeding body it is dragging after it on a rope is Georgia". The work won great popularity from the common reader and bitter attacks from the Communist critics and proletarian writers who accused him of corruption, misrepresentation, slander, and subversion; even the fact that his nephew worked as a tram conductor in Greece was used against him.[4]

Political views and last years[]

Because of his patriotic views Javakhishvili was arrested and exiled several times even during the era of Imperial Russia. After the crash of The First Georgian Democratic Republic and annexing of the country by the , he always was under special surveillance because of his views and former membership of National-Democratic Party. In 1924 he had been suspected of participating in the patriotic rebellion and was imprisoned and after series of interrogations and tortures proscribed to death. He survived only because of the "kind mood" of Sergo Orjonikidze, who was personally asked by Javakhishvili's close friends historian Pavle Ingorokva and physician . Although relations between writer and governing regime were always tense, in 1930, Javakhishvili clashed with , president of the Union of Writers and People's Commissar for Education, suspected to be Trotskyist, after the latter's ban on the classics of Georgian literature. Upon Lavrenty Beria's coming to power, the ban was revoked, and Javakhishvili for a short time gained favor. His Arsena of Marabda was republished, and both dramatized and filmed. However, he was not able to escape bitter criticism from the Bolsheviks even after he published, in 1936, the moderate A Woman's Burden (ქალის ტვირთი), an attempt at a Socialist realist novel. That was a story of a revolutionary but bourgeoisie woman, Ketevan, whose lover, a Bolshevik underground worker Zurab, persuades her to marry a Tsarist gendarme officer, Avsharov, whom she is to kill. The Soviet ideologist condemned the novel, claiming that it illustrated Bolsheviks as pure terrorists and made gendarmes too chivalrous. Soon, Beria resented Javakhishvili's refusal to seek his advice over the representation of Bolshevik activities in pre-revolutionary Georgia. Furthermore, Javakhishvili was suspected of warning the writer Grigol Robakidze of impending arrest and assisting him in defecting to Germany back in 1930. The matters went to a head when, in 1936, he was accused of praising the French author André Gide whose Retour de l'URSS and the book's praise of Georgian writers reclassified both Gide and Javakhishvili into enemies. On 22 July 1937, when the poet Paolo Iashvili shot himself in the Union of Writers building, and the Union's session went on to pass a resolution denouncing the poet's move as an anti-Soviet provocation, Javakhishvili was the sole person present to praise the poet's courage. Four days later, on 26 July, the presidium of the Union voted: "Mikheil Javakhishvili, as an enemy of the people, a spy and diversant, is to be expelled from the Union of Writers and physically annihilated." His friends and colleagues, including those already in prison, were forced to incriminate Javakhishvili as a counter-revolutionary terrorist. Only the critic left the Union's session in protest rather than give his consent to the resolution. The novelist was arrested on 14 August 1937 and tortured in the presence of Beria until he signed a "confession". He was shot on 30 September 1937. His property was confiscated, and his archives destroyed, his brother shot, and his widow sent into exile. Javakhisvhili remained censored until the late 1950s when he was rehabilitated and republished.[5] Some episodes from his biography like those from Dimitri Shevardnadze were further used by Tengiz Abuladze in his film Repentance (მონანიება).

Bibliography[]

Novels[]

- (1924) კვაჭი კვაჭანტირაძე; English translation: Kvachi Kvachantiradze (2015)

- (1925) ჯაყოს ხიზნები; English translation:Jaqo's Dispossessed

- (1926) თეთრი საყელო; English translation: The White Collar

- (1928) გივი შადური; English translation:Giwi Shaduri

- (1932) არსენა მარაბდელი; English translation:Arsena of Marabda

- (1936) ქალის ტვირთი; English translation:A Woman's Burden

Novellas[]

- (1923) ტყის კაცი; English translation: Man of the Forest

- (1925) ლამბალო და ყაშა; English translation:

- (1927) კურდღელი; English translation:

- (1928) დამპატიჟე; English translation:

- (1928) მიწის ყივილი; English translation:

- (1929) ფინჯანი; English translation: A Cup

- პატარა დედაკაცი; English translation:

Short stories[]

- (1903)

- Shoemaker Gabo (1904)

- The Kurka's wedding

- Eka

- Night of the Autumn

- Melted chain

- People's Law

- Metal sieve

- Teties

- Golden Teeth

- Ownerless

- Velvet dress

- Award

- Mususi

- (1925)

- Grandfather Dimo (1926)

- Two suns (1927)

- Five stories

- Nine Virgos (1935)

- Follower

- Two teeth

- An Avenger

- The Third

Gallery[]

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mikheil Javakhishvili. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mikheil Javakhishvili |

- ^ Rayfield, Donald (2000), The Literature of Georgia: A History: 2nd edition, p. 224. Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1163-5.

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (ed., 2007), Javakhishvili, Mikhail. Dictionary of Georgian National Biography. Retrieved on May 27, 2007.

- ^ Rayfield, p. 222-3.

- ^ Rayfield, p. 223.

- ^ Rayfield, p. 224.

External links[]

- (in Georgian) Anthology of Georgian Literature: Mikheil Javakhishvili. National Parliamentary Library of Georgia.

- 1880 births

- 1937 deaths

- Historical novelists from Georgia (country)

- Male writers from Georgia (country)

- Soviet rehabilitations

- Great Purge victims from Georgia (country)

- People from Marneuli