Morris Brown College

| |

Former names | Morris Brown Colored College |

|---|---|

| Motto | To God and Truth |

| Type | Private historically black[1] liberal arts college |

| Established | January 5, 1881 |

Religious affiliation | African Methodist Episcopal Church[2] |

| President | Kevin James[3] |

| Students | 42 (fall 2020) |

| Location | Atlanta , Georgia , United States[2] 33°45′17″N 84°24′32″W / 33.754778°N 84.408931°WCoordinates: 33°45′17″N 84°24′32″W / 33.754778°N 84.408931°W |

| Campus | 21-acre (84,984.0 m2), Urban[2] |

| Colors | Purple and Black |

| Nickname | Brownites |

| Sports | Discontinued 2003 |

| Mascot | Wolverines and Lady Wolverines |

| Website | www |

| |

Morris Brown College (MBC) is a private Methodist historically black liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded January 5, 1881, Morris Brown is the first educational institution in Georgia to be owned and operated entirely by African Americans.

History[]

Establishment[]

The Morris Brown Colored College (its original name) was founded on January 5, 1881 by African Americans affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the United States. It was named to honor the denomination's second bishop, Morris Brown, originally from Charleston, South Carolina.

After the end of the American Civil war, the AME Church sent numerous missionaries to the South to found new churches. They planted many new AME congregations in Georgia and other states, where hundreds of thousands of freedmen joined this independent black denomination.

On January 5, 1881, the North Georgia Annual Conference of the AME Church passed a resolution to establish an educational institution in Atlanta for the moral, spiritual, and intellectual growth of Negro boys and girls. The school chartered and opened October 15, 1885, with 107 students and nine teachers. Morris Brown was the first educational institution in Georgia to be owned and operated entirely by African Americans.[4] By 1898 the school had 14 faculty, 422 students, and 18 graduates.[5] For more than a century, the college enrolled many students from poor backgrounds, large numbers of whom returned to their hometowns as teachers, as education was a mission of high priority.

Fountain Hall, originally known as Stone Hall when occupied by Atlanta University, was completed in 1882. After Atlanta University consolidated its facilities, it leased the building to Morris Brown College, which renamed it as Fountain Hall. It is closely associated with the history of Morris Brown College and has been designated as a National Historic Landmark.[6]

Morris Brown College's Herndon Stadium was the site of the field hockey competitions during the 1996 Summer Olympics. The stadium is designed to seat 15,000 spectators.[2]

Embezzlement prosecution[]

By the early 2000s, eighty percent of the school's 2,500 students received financial aid from the federal government, totaling $8 million annually. Under the federal government's grant-in-aid, a college student financial aid program, accredited universities requested the Department of Education to reimburse grants in aid based on the enrollment of financially qualified students for each semester/quarter hour.

The university's registrar and accountable fiscal officer are required to jointly certify the students enrolled as full and/or part-time graduate or undergraduate students. The university also has to annually certify to its accreditation body that it is conducting an academic semester (or quarter) that the accreditor approved for overall semester/quarter length, and actual number of in-classroom clock-hours per semester (or quarter) hour to be awarded, in each classroom course offered.

A federal criminal case was filed against the former president, Dolores Cross, and the financial aid director (the accountable fiscal officer), Parvesh Singh, alleging that they had, on behalf of the university, submitted to the Department of Education (the grant administrator) false declarations of enrollment of students for certain semesters. The charges said that in the specified semesters, the students identified in the declarations had not, in fact, been enrolled. Since the grant-in-aid program's structure required the federal funds received to be applied to each individual enrolled student's account, the two school officers committed their second offense of embezzlement when they unlawfully applied these funds directly to ineligible college costs, such as salaries for personal staff, instead of applying the funds to offset individual students' enrollment expenses.

In 2002, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools revoked the college's accreditation because of its financial problems. Cross and Singh were charged in December 2004 in a 34-count indictment that accused them of defrauding the university, the U.S. Department of Education, and hundreds of students. The pair, who had first worked together at a college in Chicago, Illinois, were convicted of using the names of hundreds of students, ex-students, and people who were never enrolled in order to obtain financial aid funds that they applied for other purposes.[7]

During the time Cross held the college presidency, from November 1998 through February 2002, Singh obtained about 1,800 payments from federally insured loans and Pell grants for these students, who had no idea they would be responsible for paying off the loans, the indictment said.[8] Singh pleaded guilty to one count of embezzlement. Singh, 64, was sentenced to five years of probation and 18 months of home confinement.[7]

At the time of the 2004 indictment, Cross was teaching at DePaul University in Chicago.[9] On May 1, 2006, Cross pleaded guilty to fraud by embezzlement.[10] She agreed to pay $11,000 to the Department of Education in restitution.

On January 3, 2007, Cross was sentenced to five years of probation and one year of home confinement for the fraud. Cross, 70 years old, suffers from sleep apnea and has had a series of small strokes, factors the judge took into consideration. An additional factor the judge considered for each person was that they did not use the embezzled funds for personal profit, but to prop up the school's poor finances.[7] The initial indictment said Cross had used the funds to finance personal trips for herself, her family, and friends.[11]

The prosecutor, U.S. Attorney David Nahmias, said at the sentencing: "When the defendants arrived at Morris Brown, the college was already in serious financial condition. Thereafter, these defendants misappropriated ... money in fairly complicated ways in what appears to have been a misguided and ultimately criminal attempt to keep Morris Brown afloat."[12]

Rebuilding[]

At its peak before accreditation issues, the college had approximately 2,500 students enrolled.[13]

In 2004, Dr. Samuel D. Jolley, who had been the school's president from 1993 to 1997, agreed to return to the presidency to help the college's attempts to recover. The school hoped to have 107 students in fall 2006, the same number when the school opened in 1881, but failed to meet that goal.[10] Tuition in the fall semester of 2006 was $3,500, but without accreditation, students cannot obtain federal or state financial aid for their tuition and other school expenses.

By February 2007, MBC had 54 students in two degree programs, supported by 7 faculty and staff employees.[14] After the sentencing of two former administrators, the chair of the college's board of trustees, Bishop William Phillips DeVeaux, issued a press release stating the college would move forward and that "This sad chapter in the college's history is now closed."[12]

In addition to civil lawsuits filed by former and current students, Morris Brown faced a civil suit for defaulting on a $13 million property bond, a case that could have led to foreclosure on some of the college's most historic buildings, including its administration building. The complaint asked for $10.7 million in principal owed on the loan agreement, $1.5 million in interest, and a per diem of $2,100 for each day Morris Brown does not pay.

In December 2008, the City of Atlanta disconnected water service to the college because of an overdue water bill.[15] The debt was paid and the service restored.

Radio personality Tom Joyner made several offers to buy the troubled college from 2002 through 2004, during the worst of the accreditation and fraud crises. In 2003, his charitable foundation gave the school $1 million to assist with its immediate needs.[9]

The school faced foreclosure in September 2012.[16] The college filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in an attempt to prevent foreclosure and sale of the school at auction.[17]

In June 2013, Morris Brown's board of trustees rejected a $9.7 million offer from the city of Atlanta. However, negotiations continued and mid-year in 2014 Morris Brown reached an agreement with Invest Atlanta, Atlanta's economic development agency.[18] The offer eliminated the school's $35 million debt by purchasing the 37 acres on which the college sits, paying the school's creditors, and paying $480,000 in back pay owed to professors and staff. The college will be able to retain use of several historic buildings for educational purposes. The city's administration wishes to revitalize the area around Morris Brown; the site of the new Atlanta Falcons stadium is just east of the campus. Mayor Kasim Reed said that the city has no interest in operating the school, and that it would be illegal for them to do so.[19]

Several of Morris Brown's buildings are in an extreme state of disrepair and have been heavily damaged, including Herndon Stadium, the Middleton Twin Towers dorm, Gaines Hall, and Furber Cottage. Gaines Hall was heavily damaged by a two-alarm fire in August 2015.[20] Mayor Reed indicated in August 2015 that he would like to see the city help preserve the building.[21]

As of fall 2018, the college had less than 50 students enrolled. The college received approximately 2,000 applications but interest dropped significantly once applicants were notified they can not receive financial aid because the college was not accredited.[22][13]

In 2019, Morris Brown College was approved as an institute of higher learning by the Georgia Nonpublic Postsecondary Education Commission (GNPEC). The approval is a notable step towards regaining full accreditation.[23] In 2021, the college became beneficiaries of a $30 million investment that partners them with Hilton to establish a new hotel on campus and reestablish a hospitality management degree program to train Brownites[24][25] and its application for accreditation candidacy through the Transnational Association of Christian Colleges and Schools (TRACS) was approved, allowing the college to once again receive federal financial aid and other funds.[26]

Academics[]

Morris Brown offers baccalaureate degrees in Management, Entrepreneurship, and Technology (for traditional students) and Organizational Management and Leadership (for Adult Degree matriculants).[2]

Accreditation[]

Morris Brown has been unaccredited since 2003.[27] Until 2003, Morris Brown was accredited by a regional accreditor, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). Morris Brown was more than $23 million in debt and was on probation in 2001 with SACS for shoddy bookkeeping and a shortage of professors with advanced degrees. In December 2002, SACS revoked Morris Brown's accreditation. Almost eight years later, the college settled its nearly $10 million debt with the Department of Education.[28]

In March 2019, the college's leaders announced that the college was applying for accreditation through the Transnational Association of Christian Colleges and Schools (TRACS) within 12 to 18 months.[29] The college's application for candidacy was accepted by TRACS in early 2021, enabling the college to once again receive federal financial aid and other funding.[26]

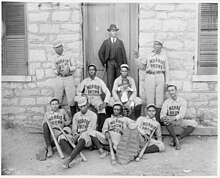

Athletics[]

In the early 2000s, the college briefly had an independent NCAA Division I athletics program.[30] Prior to the Division I transition, the college was a founding and active member of the NCAA Division II Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference between 1913 and 2000.[31]

The Morris Brown Wolverines football program played at Herndon Stadium on campus until the athletic program was discontinued in 2003. Despite an inactive athletics program, Morris Brown has continued its homecoming tradition every fall semester on campus.[32]

The Marching Wolverines[]

Morris Brown College was well known for its popular and sizable marching band program, "The Marching Wolverines", and danceline "Bubblin Brown Sugar." Both were strongly featured in the 2002 box office hit Drumline and invited to perform at the first Honda Battle of the Bands event in 2003.[33] In 2006, the rappers OutKast released a song named "Morris Brown" that featured the marching band.

Due to accreditation problems at the college in the 2000s, the band program eventually discontinued.

Notable alumni[]

- Hosea Williams – civil rights activist

- Nene Leakes – American television personality and entrepreneur

- Jean Carn – jazz and pop singer

- Kimberly Alexander – member of the Georgia House of Representatives

- Carl Wayne Gilliard – member of the Georgia House of Representatives[34]

- Carrie Thomas Jordan – educator

- James Alan McPherson – Historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning author

- Billy Nicks – former head football coach of Morris Brown and Prairie View A&M University

- Sommore – comedian and member of the Queens of Comedy

- Charles W. Chappelle – attended late 1880s; Aviation pioneer, international businessman, president of the African-American Union, electrical engineer and architect/construction

- Donzella James – former member of the Georgia State Senate

- Beverly Harvard – first black female police chief of Atlanta[35]

- George Atkinson – former NFL defensive back for the Oakland Raiders

- Solomon Brannan – former AFL defensive back for the Kansas Chiefs and New York Jets

- Ezell Brown – Educational entrepreneur, founder of Education Online Services Corporation

- Donte Curry – former NFL linebacker for Carolina Panthers and Detroit Lions

- Tommy Hart – former NFL defensive end for the San Francisco 49ers

- Alfred Jenkins – former NFL and WFL wide receiver Atlanta Falcons 1975–1983 and Birmingham Americans 1974

- Ezra Johnson – former NFL defensive end for the Green Bay Packers and Indianapolis Colts

- Greg Grant – former NBA player

- Howard Simon Mwikuta – former kicker for the Dallas Cowboys and the first native-born African to play in the NFL[36][37]

- Teck Holmes – Castmate on MTV's The Real World: Hawaii, actor, and TV personality[38]

References[]

- ^ "List of HBCUs – White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities". 2007-08-16. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Visitor". Morris Brown College. Archived from the original on 2008-01-08. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^ "Dr. Kevin James named 19th President of Morris Brown College". Morris Brown College (Press release). May 18, 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "Morris Brown College founded". The African American Registry website. Archived from the original on 2007-12-01.

- ^ Hawkins, John R., ed. (1898). "Our Schools from Latest Reports". The Educator. Educational Department of the A.M.E. Church. 1 (no. 1): 47.

- ^ "Stone Hall, Atlanta University". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Former college president gets probation for $3.4M embezzlement". Associated Press. 3 January 2007. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ Fain, Paul (10 December 2004). "Federal Indictment Accuses Former Morris Brown President and Aid Officer of $5-Million Fraud". Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Powell, Tracie (30 December 2004). "Former Morris Brown College president, financial aid director indicted for fraud". Black Issues in Higher Education. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Romano, Lois (1 May 2006). "Morris Brown College". Washington Post. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Ex-President of Morris Brown College Pleads Guilty". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 1 May 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ex-president of Morris Brown gets probation". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. 4 January 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "'We're still here': Morris Brown College president, alums talk about the institution's slow road back to prominence – The Atlanta Voice". The Atlanta Voice – Atlanta GA News. 28 June 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ Jones, Andrea (2007-02-24). "Morris Brown Marks 126 Years". Metro News, 1B. Atlanta Journal Constitution.

- ^ "Water Shut Off At Historic Atlanta College For Unpaid Bill". WSB-TV. December 21, 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ Ernie Suggs (August 24, 2012). "With foreclosure looming, Morris Brown College on the brink". Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Morris Brown College seeks federal protection, hopes to prevent auction of campus". Atlanta Journal Constitution. August 25, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ Leslie, Katie. "Invest Atlanta approves purchase of Morris Brown College". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ "Morris Brown trustees turn down taxpayer money". Associated Press. June 8, 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Atlanta Preservation Center". Atlantapreservationcenter.com.

- ^ "Reed: We are going to find a way to preserve Gaines Hall". Atlanta Business Chronicle.

- ^ Wheatley, Thomas (13 April 2017). "Morris Brown College used to enroll 2,500 students. Today, there are 40". Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Morris Brown has been approved as an institute of higher learning".

- ^ https://www.bizjournals.com/atlanta/news/2021/02/25/hilton-morris-brown-college-build-30-million-hotel.html?ana=newsbreak

- ^ "Morris Brown College receives $30 million investment for hotel development project | the Atlanta Voice". 3 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Whitford, Emma (April 14, 2021). "Morris Brown Earns Accreditation Candidacy After 19 Years". Inside Higher Ed.

- ^ Thomas Wheatley (April 2017). "Morris Brown College used to enroll 2,500 students. Today, there are 40". Atlanta Magazine. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Associated Press (August 23, 2011). "Morris Brown pays off debt to US government". Retrieved August 23, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Downey, Maureen. "Blog: Morris Brown: Can this college be saved? Leader says it can". AJC – Atlanta Journal Constitution.

- ^ "Morris Brown College is surviving, hoping to thrive again". 21 October 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "On Road to Losin' for Morris Brown". Associated Press. 16 December 2001. Retrieved 28 February 2019 – via LA Times.

- ^ "And it don't stop: Morris Brown College homecoming 2016". November 2016.

- ^ "Band – Morris Brown College". Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Representative Carl Wayne Gilliard".

- ^ "Beverly Harvard: Atlanta's first black female police chief".

- ^ "Who Was the NFL's Biggest African Star?". 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Touchdown: Many Africans have taken the NFL by storm".

- ^ "Teck Holmes".

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morris Brown College. |

| Archives at | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| How to use archival material |

- Official website

- "Digital Collection: Morris Brown College Photographs". RADAR. Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

- "Digital Collection: Morris Brown College Yearbooks". RADAR. Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

- "Digital Collection: The Wolverine Observer (student newspaper)". RADAR. Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

- "Digital Collection: Morris Brown College Catalog". RADAR. Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

- Morris Brown College

- African Methodist Episcopal Church

- Historically black universities and colleges in the United States

- Universities and colleges affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church

- Private universities and colleges in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Unaccredited institutions of higher learning in the United States

- Educational institutions established in 1881

- Universities and colleges in Atlanta

- Old Fourth Ward

- 1881 establishments in Georgia (U.S. state)

- English Avenue and Vine City