Murder of Joe Campos Torres

Jose Campos Torres | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | José Campos Torres December 20, 1953 |

| Died | May 5, 1977 (aged 23) Houston, Texas |

| Cause of death | Blunt-force trauma |

| Body discovered | Floating in the Buffalo Bayou Houston, Texas |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation | Glass contractor |

| Known for | Police murder victim |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Military career | |

| Buried | 29°55′53″N 95°27′02″W / 29.931250°N 95.450472°W |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1974–1976 |

| Rank | |

| Website | Solidarity Walk Houston |

José Campos Torres (December 20, 1953 – May 5, 1977) was a 23-year-old Mexican-American and veteran who was beaten by several Houston Police Department (HPD) officers, which subsequently led to his death. He had been brutally assaulted by a group of on-duty police officers on May 5, 1977, after being arrested for disorderly conduct at a bar in Houston's Mexican-American East End neighborhood.

After Torres' arrest at the bar, the officers took him to the city jail for booking. But his injuries were so extensive that a supervisor instead ordered the officers to take Torres to a local hospital for immediate medical treatment. The officers did not comply with the order, and three days later, his severely beaten dead body was found floating in the Buffalo Bayou, a creek on the outskirts of downtown Houston.

Following the discovery of Torres' body, two of the arresting officers, Terry W. Denson and Stephen Orlando, were charged with murder. Three other officers were fired from the HPD by Police Chief B.G. Bond, but no criminal charges were brought against them. A rookie officer who was present at the scenes of Torres' torture and drowning was a key witness for the prosecution. Denson and Orlando were convicted at the state level for Torres' death, and found guilty of negligent homicide (a misdemeanor). An all-white jury sentenced the officers to one year's probation and a one dollar fine.

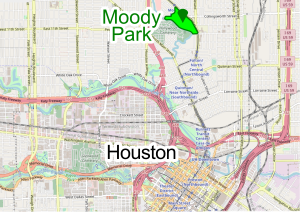

The racial composition of the jury, and the minimized criminal convictions and sentencing sparked community outrage, leading to multiple protests[2] and the 1978 Moody Park Riot.[3] His death led to negotiations between advocacy-based non-profits and HPD officials, which resulted in the addition of policies that addressed police-community racial relations.

Following the State of Texas' controversial convictions of the two former officers, the Torres case was reviewed at the federal level by the U.S. Department of Justice, which led to three of the officers' federal convictions for violating Torres' civil rights.

Torres' murder generated significant newspaper coverage across the United States. Initially, it focused on his assault and drowning, but soon it turned its attention to the historic racism, lack of HPD over-watch and the recurring absence of state and federal investigations. Later, a locally produced documentary appeared, entitled The Case of Joe Campos Torres, which focused on the history of police misconduct in Houston. In the year following his death, a poetic song by vocalist and activist Gil Scott-Heron appeared, titled "Poem for José Campos Torres", reflecting the struggles surrounding racism and police brutality.

Background[]

José Campos Torres was born to José Luna Torres Jr. in a poor family of Mexican descent. The family resided in a barrio in Houston, Texas. Torres achieved only an eighth-grade education. It is believed that a side effect of the poverty he experienced is what led to his constant struggle with his social demeanor.[4][5]

According to family and friends, Torres' dream was to run and own a karate school. He wanted to open the school near his East End neighborhood, allowing him to teach young people the art of self-defense. To pursue his dream, he realized that he needed a General Education Diploma (GED), a driver's license, and a job, preferably as a lineman with a telephone company.[4][6]

Richard Vargas, Torres' longtime friend, said that when Torres was 23 years old, he still felt emotionally lost, and was fighting a sporadic problem with alcohol. Torres would occasionally become very intoxicated, and his friends and family said that it was this that would trigger his aggression, in wanting to fight. Torres' younger brothers, Gilbert, 20 and Ray, 16 acknowledged that Torres had an occasional problem with alcohol abuse. "Alcohol really got to him sometimes." Vargas said, "Sometimes when he drank a lot he wanted to fight ... I didn't like to be around Joe when he was drinking. When he got drunk, he'd start practicing his karate. He'd yell and kick and punch at the air." When Torres was a teenager he got into a lot of fights, and yet he had confided to Vargas that he knew that the fighting would get him nowhere.[7]

Torres' father said that his son spent two years in the United States Army. During his military service, he was accepted to the United States Army Rangers, undergoing training at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. While in training, he was separated from the service in September 1976, under a 'general discharge.' It was reported that his abuse of alcohol and anger outbursts are what ultimately led to his early release from the U.S. Army. His brother Gilbert said, "Before the service, Joe was bum and a drifter, but after he got out he really cut down on the drinking ... The normal Joe was different from the drunk Joe." He said, "The drunk Joe got rowdy easy and he [take] things the wrong way sometimes."[7][8][9][10]

Just two weeks before his death, Torres found employment as a glass contractor, earning $2.75 an hour. Vargas said that Torres had difficulty staying employed ever since his discharge from the U.S. Army. He said that Torres resented his being restricted to tedious, low paying jobs due to his low education level and nominal military skills. Even though Torres had received training in the military as a telecommunications lineman, not having his GED and a driver's license were barriers to employment with a potential telecommunications provider.[7][10]

Vargas said, Torres' true passions were physical fitness and the art of karate. After his return from the U.S. Army he was working to receive a black belt (expert) rating in karate. In addition to his progress in karate, he also underwent weight training and jogged, frequently attaching weights to his feet.[7][11]

Incident[]

Shortly before midnight on May 5, 1977, Torres was at the Club 21, a bar in Houston's predominantly Hispanic East End neighborhood, wearing his army fatigues and military boots. He had apparently been drinking, and police officers arrived, arresting him for disorderly conduct. The six officers who responded took Torres to "The Hole", a spot behind a warehouse overlooking Houston's Buffalo Bayou, and beat him there. The officers then took Torres to the city jail, who refused to process him due to his injuries. A supervisor ordered to take him to Ben Taub Hospital, but instead of doing so, the officers took him back to "The Hole", and pushed him off a wharf into the water. Torres's body was found three days later.[12]

Trials[]

Officers Terry W. Denson and Stephen Orlando were tried on state murder charges.[13] They were convicted of negligent homicide and received one year of probation and a one dollar fine.[14] In 1978, Denson, Orlando and fired officer Joseph Janish were subsequently convicted of federal civil rights violations, and served nine months in prison.

Moody Park Riot[]

| 1978 Moody Park Riot | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Moody Park; Houston, Texas | ||||

| Date | May 7–8, 1978 | |||

| Location | Moody Park; Houston, Texas, U.S. 29°47′32″N 95°21′51″W / 29.79231°N 95.36425°W | |||

| Caused by | Reaction to light sentencing of police officers in the murder of Joe Campos Torres | |||

| Goals | • Civil rights • Ending police brutality • Ending police racism | |||

| Methods | • Arson • Assault • Looting • Rioting • Shooting • Property damage | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

| ||||

| Number | ||||

| ||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||

| ||||

| "Free The Moody Park 3" legal fund started | ||||

On the one year anniversary of José Campos Torres' murder a riot was started at Moody Park located in Houston's Near Northside neighborhood.[15] The riot broke out on the evening of Saturday, May 7, 1978, at approximately 7:30 pm, once a Cinco de Mayo fiesta event ended at the park. Between five and six thousand people attended the celebration.[16]

It was the greatest miscarriage of public trust by police officers in my 27 years of wearing a badge.

— Harry Robinson, Former Houston Police Chief, Houston History Magazine[17]

Police arrived at the park in response to a call for an incident of disorderly conduct. It remains unclear on how the riot started. Some reports reflect that the officers were making a few arrests and this is when people in the event began yelling, "No you are not taking them" and "You'll kill them the way you killed José Campos Torres". The crowd's initial yelling immediately lead people to begin chanting in unison "Justice for Joe Torres" "Viva Joe Torres" and "A Chicano's life is worth more than a dollar!" The crowd then began throwing bottles and rocks at the officers.[16][18][19]

The Fulton Village shopping center's stores at 2900 Fulton street, were looted and set on fire. Abe Weiner, an owner of a department store in the shopping center, said it took the fire department over an hour to respond to his emergency 9-1-1 call for help. Three large buildings and two smaller ones in the shopping center were looted and stripped by fires.[20] The rioting escalated to over a ten-block area adjacent to Moody Park. A total of six stores and one gasoline station were set on fire.[16][18][21]

Officers were promptly deployed in riot gear to try and control the gathering of approximately 1,500 people according to police (other estimates reflect 150–300) who took part in the riot.[22] Some rioters had flipped cars over and set them on fire, fourteen of the eighteen smashed and burned cars were police cars.[18] The property damage of businesses and police vehicles reached $500,000. At least 28 people were taken into custody after the violence started in the predominantly Mexican-American neighborhood. The incident and all the fires were finally under control at 3:00 am.[16][23]

Houston police officer Tommy A. Britt suffered a broken leg when hit by a car while trying to close off one of the streets involved in the riot. The driver Rogelio Castillo did not pull over, but was apprehended a few blocks away from the incident.[24] The first news reporters to arrive at the scene were KPRC-TV reporter Jack Cato, and reporter/photographer Phil Archer. Both were beaten and stabbed.[25] Cato suffered a punctured lung from a stab wound in the lower back. Archer was hit in the face with a brick and then stabbed in the left hip while lying unconscious on the pavement. Rioters attempted to smash the camera he was carrying. It was later recovered, badly damaged. Cato managed to bring out the video shot during the attack which shows some of the rioters surrounding a burning Houston Fire Department ambulance supervisor's car.[24] The riot's violence left a total of five police officers, two news personnel and eight rioters injured and hospitalized. None of the fifteen hospitalized people died due to their injuries.[17][26][27]

Apology[]

In June 2021, police chief Troy Finner apologized to the Torres family, calling the killing "straight-up murder."[28]

Popular culture[]

Books[]

Author Dwight Watson dedicated the chapter "The Storm Clouds of Change: The Death of José Campos Torres and the Emergence of Triracial Politics in Houston" in the book Race and the Houston Police Department, 1930–1990 A Change Did Come. The chapter covers the impact of Torres' murder on society and changes in Houston's policing policies.[29][30]

It brought people who were very conservative and very quiet to become very vocal and very political and people began to hold the police accountable.[31]

— Dwight Watson, "Moody Park–The Aftermath", interview by Houston Public Media

Music[]

Poem for José Campos Torres[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Vocalist and activist Gil Scott-Heron, known as the "Godfather of Rap" and for his sociology charged spoken word performances in the '70s. Scott-Heron's best-known recording is the 1971 released "The Revolution Will Not be Televised", this artwork characterizes unashamed consumerism.[32][33]

Scott-Heron's artistry based on self-fortitude and resentment of racism spanned across racial cultures and was popular among both African-Americans and Latinos. In 1978, the year following Torres' murder, he targeted community awareness of the murder and created a poetic song focusing on America's systemic abuse of Asian-Americans, African-Americans and Hispanics in the heartfelt "Poem for José Campos Torres."[32][34] The song was released as track 4 of the album titled; The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron.[35]

Scott-Heron saw Torres as a brother and made his familial tie to Torres in the lyrics, here is a quote from the song:[36]

♪ But brother Torres, common ancient bloodline brother Torres is dead ♪

♪ I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this ♪

♪ I had said I wasn't going to write no more words down ♪

♪ About people kicking us when we're down ♪

♪ About racist dogs that attack us and drive us down, drag us down and beat us down ♪

♪ But the dogs are in the street ♪— Gil Scott-Heron, "Poem for José Campos Torres", Album: The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron

El Ballad De José Campos Torres[]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

(0:53 - 5:29) |

Charanga Cakewalk is the stage name for Michael Ramos, a self-described Latino Chicano Mexican who is also a citizen of the world. Ramos, from Austin, TX, is an instrumental artist who passes a distinguishing sound of Latino music onto the next generation of artistry. Ramos has played numerous instruments in studios and on-tours for John Mellencamp, Patty Griffin, Los Lonely Boys, Paul Simon and multiple notable artist.[37][38] His artwork is self-styled as Cumbia-Tronic that soars between absorbed Electronic Dance and cultivated genres of Cumbia, Ranchera, Folklorica, and Garage Rock.[39][40]

In March 2006, Charanga Cakewalk released the album Chicano Zen. The album has multiple instrumental songs, track 11 the closing song is the instrumental titled: "El Ballad de José Campos Torres", with a synth, accordion and piano drift inspired by the life of Torres:[41][42]

So many people think of what happened to José Campos Torres, but I got [to] thinking about him as a person, who he was, what he felt, how he lived.[43]

— Michael Ramos, The Zen of Revolution

Moody Park Riot (José Campos Torres)[]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

In 2014 Nuño Records published, via SoundCloud, the song "Moody Park Riot (José Campos Torres)" written by Juan Nuño performed by Jesse James at Houston, TX. The lyrics depict Torres' beating and drowning along with events tied to the 1978 Moody Park Riot.[44]

Television[]

Interview with Janie Torres[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Art Browning hosted a television interview with Torres' little sister Janie Torres. The episode, produced by Green Watch Television (GWTV), is titled: "Joe Campos Torres, 40 years ago", first aired: Wednesday, April 26, 2017, duration: 24 min. When Browning asked about her thoughts on the establishment of Black Lives Matter she replied:[45]

"Wow I was amazed, it was something that was so well, well over due for the people" she continued, "Justice is equal, justice is what we deserve that's all we want, we don't want anymore any less."

— Janie Torres, "Joe Campos Torres, 40 years ago" (interview)

At the closing of the interview, Janie Torres, who was only a 10-year-old when her brother's life was taken, announced plans for an annual solidarity walk in memory of her brother. The walk is targeted across all generations with the focus on awareness of police racism across the nation. The second annual walk and rally occurred on May 6, 2017, in Houston, Texas. Janie plans on continuing to hold the walks annually, to be held on the yearly anniversaries of her brother's murder. For social awareness she has posted the walk on a Facebook homepage; "Joe Campos Torres Solidarity Walk For Past & Future Generations".[45]

Films[]

The Case of Joe Campos Torres[]

The documentary The Case of Joe Campos Torres recounts the calendar of events and ensuing community-protest assemblies, community/police department discussions, along with the legal actions taken by the Torres family against the Houston Police Department and the City of Houston.[46][47]

Filmed around Houston, the documentary records the Latino communities reaction to what they witnessed as an act of racial injustice against their population. The documentary, approximately 30 – 40 minutes in length, replays raw footage taken from local news station's archives. The footage is used as a reminder to viewers that before video cameras were able to bring police misconduct to light, the family of Torres had to rely on community support to help them find justice.[48]

The film was produced in 1977 by Tony Bruni and Houston's KPRC-TV, Channel 2. Carlos Calbillo both wrote and edited the film and it was reported by John Quiñones, who is now with ABC News and hosts the series What Would You Do?.[48]

See also[]

- Death of Freddie Gray

- Death of John Hernandez

- Chad Holley

- Killing of Santos Rodriguez

- Wilmington Ten

- List of killings by law enforcement officers in the U.S.

- Police brutality in the United States

- Houston riot of 1917

References[]

- ^ Administration, National Cemetery. "Nationwide Gravesite Locator". gravelocator.cem.va.gov. United States of America, Veterans Administration. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ KPRC-TV (1977). "Protests Against Police Brutality (1977)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ KPRC-TV (1978). "Moody Park Riot (1978)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Nolan, Joe; Reyes, Raul (May 15, 1977). "Interactive: Joe Campos Torres | Torres Friends say he had his dreams—and his drawbacks". Houston Chronicle. Vol. 76, no. 212. Hearst Newspapers, LLC. p. 1. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ Katz, Donald (2001). "The "Misdemeanor Murder" of Joe Campos Torres". The Valley of the Fallen and Other Places (1st ed.). New York: AtRandom.com. ISBN 0679647228. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ "Abilene Reporter-News from Abilene, Texas | Murder Charges Filed Against Police Officer". United Press (UP). Houston (UP): Newspapers.com. May 12, 1977. p. 45. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Nolan, Joe; Reyes, Raul (May 15, 1977). "Interactive: Joe Campos Torres | Torres Friends say he had his dreams—and his drawbacks". Houston Chronicle. Vol. 76, no. 212. Hearst Newspapers, LLC. p. 12. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ Salinas, Lupe S. (July 1, 2015). U.S. Latinos and Criminal Injustice. Michigan State University Press. p. 236. ISBN 9781628952353. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Steven Harmon (2002). "Criminal Justice in the 1970s". The Rise of Judicial Management in the U.S. District Court, Southern District of Texas, 1955-2000. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780820327280.

- ^ a b Curtis, Tom (September 1977). "Texas Monthly | Support Your Local Police (or else)". Domain : The Lifestyle Magazine of Texas Monthly. Emmis Communications. 5 (9): 85. ISSN 0148-7736. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ Mendoza, Lydia; Nicolopulos, James; Strachwitz, Chris (1993). Lydia Mendoza a Family Autobiography (in Spanish). Houston, Tex.: Arte Público. p. 353. ISBN 9781558850668. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ^ "Nation: End of the Rope". Time. April 17, 1978. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ KPRC-TV (1977). "Grand Jury Investigation into the Death of José Campos Torres (1977)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Jack (May 8, 2008). "Echos of Moody Park: 30 years later". KUHF-FM. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ KPRC-TV (1978). "Moody Park Riot (1978)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Houston history: An ugly Cinco de Mayo celebration". ABC13 Houston. HOUSTON (KTRK): ABC Inc. KTRK-TV Houston. May 6, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Block, Robinson (January 2, 2012). "Moody Park: From the Riots to the Future for the Northside Community". Houston History Magazine. 9 (3): 20–22. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ a b c Williams, Jack (May 7, 2008). "Moody Park Part 2- The Riot | Houston Public Media". Houston Public Media. University of Houston. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ Márquez, John D. (2014). "Neoliberalism and Its Aftermath". Black-Brown Solidarity: Racial Politics in the New Gulf South. University of Texas Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780292753891.

... all while chanting slogans like "Viva Joe Torres!" "Justice for Joe Torres!" and "A Chicano's life is worth more than a dollar!"

- ^ "Moody Park Riot (1978)" [film]. KRPC-TV. The Texas Archive of Moving Image.

- ^ Boyd, John (April 28, 2015). "Remembering Joe Campos Torres and Houston's Moody Park riots". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

Image 9 of 37 - Caption

- ^ León, Arnoldo De (2001). "XI Moderation and Inclusions, 1975 -1980s". Ethnicity in the Sunbelt : Mexican Americans in Houston (1st Texas A & M University Press ed.). College Station: Texas A & M University Press. p. 211. ISBN 9781585441495. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

The mob of about 1,500 according to police (other estimates say 150-300) ...

- ^ Cory, Bruce (May 15, 1979). "2 Who Incited '78 Houston Riot Fined, Put on 5-Year Probation". Washington Post. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ a b KPRC-TV

- ^ KPRC-TV (1978). "KPRC Newsmen Injured During Moody Park Riot (1978)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ ABC Inc., KTRK-TV Houston, ed. (October 22, 2017) [1978]. Moody Park Riots ABC13 Coverage (Television production). Houston, TX: ABC 13. Event occurs at 11:55. Retrieved December 9, 2017 – via Mashpedia.

Police are talking with the District Attorney on what charges need to be filed in connection with the disturbance. Charges have already been filed against Rogelio Castillo in connection with the incident, in which the police officer was struck by the car.

- ^ Jo Ann Zuiga; S.K. Bardwell (October 19, 1998). "10/19/98 Houston Chronicle Article on Pedro Oregon Navarro Shooting". www.lulac.net. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

... lack of punishment prompted the Moody Park riot, which sent 15 people to the hospital.

- ^ "Houston chief calls 1977 police killing 'straight-up murder'". Associated Press. June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Macías, Francisco (May 5, 2015). "Remembering José "Joe" Campos Torres's Last Cinco de Mayo". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ Watson, Dwight (2005). Race and the Houston police department, 1930-1990 : a change did come (1st ed.). College Station, Texas: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 9781585444373. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Jack (May 8, 2008). "Moody Park- The Aftermath". Houston Public Media. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Contreras, Felix (May 8, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron Dies: Rhymes For La Revolución". NPR. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Stephen (November 16, 2009). "The legendary godfather of rap returns". Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ "Antiwar Songs (AWS) - José Campos Torres". Antiwarsongs. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ "Mind of Gil Scott-Heron". amazon.com. Tvt. January 30, 2001. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron – Jose Campos Torres Lyrics | Genius Lyrics". Retrieved December 16, 2017.

José Campos Torres | Produced by Gil Scott-Heron | Album The Mind of Gil Scott Heron

- ^ "Chicano Zen by Charanga Cakewalk on Apple Music". itunes.apple.com. Apple Inc. March 28, 2006. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Chuck, ed. (April 1, 2006). "Reviews - Singles". Billboard. Vol. 118, no. 13. New York, NY: Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. 46. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Acosta, Belinda (May 12, 2006). "Charanga Cakewalk | Record Review". Austin Chronicle Corp. Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ "Summer Sessions 2007 (Visit the Getty)". www.getty.edu. Los Angeles, CA.: J. Paul Getty Trust. 2007. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

Prior to forming his "cumbia-tronic" project, Ramos played keyboards and accordion for artists like John Mellencamp, Patty Griffin, Paul Simon, and the Rembrandts.

- ^ "Charanga Cakewalk - Chicano Zen". Discogs. 2006. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

Track:11, Title: El Ballad De Jose Campos Torres, Duration: 4:50

- ^ "El Ballad de Jose Campos Torres". napster.com. March 28, 2006. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Marsh, Dave (August 18, 2006). "The Zen of Revolution: Michael Ramos' Charanga Cakewalk". Austin Chronicle Corp. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ "Moody Park Riot (Jose Campos Torres) | written by Juan Nuno performed by Jesse James at Houston". soundcloud.com. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Browning, Art (May 3, 2017). "Joe Campos Torres, 40 years ago (GWTV 2017-04-26) Greenwatch TV". Houston, TX: Green Watch Television (GWTV). Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ "May 8: The Case of Joe Campos Torres (Film)". doscentavos.net. May 2, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ "Shared Histories Film Screening and Panel Discussion: The Case of Joe Campos Torres". Arts Hound. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Ruiz, Raymond (July 28, 2011). ""The Case of Joe Campos Torres" debuts to a packed house - The Venture". The Venture. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

External links[]

- Joe Campos Torres Solidarity Walk For Past & Future Generations Facebook page

- Press Conference about Moody Park Riot (1978), Texas Archive of the Moving Image

- Police misconduct in the United States

- Race riots in the United States

- 1954 births

- May 1977 crimes

- 1977 deaths

- 1977 in Texas

- 1977 murders in the United States

- American manslaughter victims

- American murder victims

- American people of Mexican descent

- Civil rights protests in the United States

- Crimes in Houston

- Deaths by person in the United States

- Deaths in police custody in the United States

- History of Houston

- History of racism in Texas

- Houston Police Department

- Houston Police Department officers

- Law enforcement in Texas

- Manslaughter victims

- May 1977 events in the United States

- Mass media-related controversies in the United States

- Mexican-American culture in Houston

- Mexican-American history

- Murder in Texas

- Murdered Mexican Americans

- People from Houston

- People murdered by law enforcement officers in the United States

- People murdered in Texas

- Police misconduct

- Protests in the United States

- Race and crime in the United States

- Racially motivated violence against Hispanic and Latino Americans

- Racially motivated violence in the United States

- Riots and civil disorder in Texas

- United States Army soldiers

- 1970s in Houston