Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

| |

| |

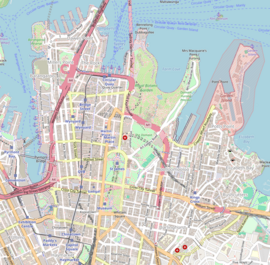

Location in Sydney central business district | |

| Established | 1991 |

|---|---|

| Location | George Street, Sydney, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°51′36″S 151°12′32″E / 33.860019°S 151.208999°ECoordinates: 33°51′36″S 151°12′32″E / 33.860019°S 151.208999°E |

| Type | Contemporary art |

| Collections | Raminging, Maningrida, Arnott's, Smorgon |

| Collection size | 4,500 |

| Visitors | 1,206,243 (2016)[2] |

| Founder | John Power; University of Sydney |

| Director | |

| Chairperson | Lorraine Tarabay |

| Curator | Lara Strongman |

| Architect | Sam Marshall |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | mca |

The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), located in George Street in Sydney's The Rocks neighbourhood, is a museum solely dedicated to exhibiting, interpreting and collecting contemporary art, both from across Australia and around the world. It is housed in the Art Deco-style[3] former Maritime Services Board Building on the western edge of Circular Quay.

While the museum as an institution was established in 1991, its roots go back a half-century earlier. Expatriate Australian artist JW Power provided for a museum of contemporary art to be established in Sydney in his 1943 will, bequeathing both money and works from his collection to the University of Sydney, his alma mater. The works, along with others acquired with the money, were exhibited mainly as a travelling collection in the decades afterward, stored in two different university buildings, until the MSB building became available.

At first it was known as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. The new museum rapidly outgrew its space, and after two proposed expansions failed, a design by local architect Sam Marshall met with sufficient approval to raise money for its construction. From 2010 the building underwent an A$58 million expansion and re-development,[4] reopening in March 2012 as the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia.[5][6]

Power's original intent was for the museum to exhibit contemporary art from all over the world, with work by Australian artists shown only if it was relevant to the other works, but its focus has since changed primarily to Australian art. The museum's collection contains over 4,000 works by Australian artists acquired since 1989. They span all art forms with strong holdings in painting, photography, sculpture, works on paper and moving image, as well as significant representation of works by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists. The museum runs programs to engage the interest of youth and disabled communities in appreciating and making art.

History[]

Maritime Services Board (MSB) Building[]

The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia is located just south of the landing spot of the First Fleet. The site originally housed two Commissariat Stores. Joseph Foveaux designed the first, built in 1809 following the previous year's Rum Rebellion. The second, facing George Street North, was built in 1813 under Governor Lachlan Macquarie's authority; both used convict labour.[7]

The state government assumed control of the Commissariat Stores in 1901 and leased them to commercial tenants. In 1937, the Circular Quay Planning Committee recommended the buildings be demolished to build a new office for the Maritime Services Board (MSB), which had been displaced by the Circular Quay Railway. Demolition was completed in 1939; construction was halted the following due to World War II. Work resumed in 1944 and the offices opened eight years later.[7]

Power Gallery of Contemporary Art[]

The establishment of the MCA was mandated in the will of Australian expatriate artist JW Power (1881–1943), who bequeathed his personal fortune to the University of Sydney with the express purpose of informing and educating Australians in the contemporary visual arts.[citation needed]

In December 1970 the University of Sydney also received the Seymour Bequest for the purposes of a performing arts centre, and sought to combine the two bequests into an arts complex that would include within it the Seymour Centre and the Power Institute facilities, including a home for the Power Gallery.[8][9] The Seymour Centre was opened in 1975 without designs for the Power Institute of Fine Arts being integrated into the final building.[citation needed]

This collection of artworks took the form of the 'Power Gallery of Contemporary Art', a travelling collection without a permanent address. Between John Power's death and the eventual establishment of the museum, the collection was mainly housed in the University of Sydney's Fisher Library during the 1970s. It was exhibited in the Madsen Building on campus between 1980 and 1989.[9]

Museum of Contemporary Art[]

With the relocation of the Maritime Services Board (MSB) from the 1949 built five-storey building to larger premises in 1989, the building and site was donated by the Government of New South Wales to the Museum of Contemporary Art.[10] Funded by the University of Sydney and the Power Bequest, restoration and refurbishment of the building commenced in 1990 under the direction of Andrew Anderson of Peddle Thorp/John Holland Interiors and in November 1991 the Museum of Contemporary Art officially opened.

Extensions made in 2010–2012 were to a design by Sydney architect Sam Marshall. The new extension, called the Mordant Wing, opened in March 2012.[1][11] The wing was named after the chairperson of the museum's board, Simon Mordant (2010–2020). In July 2020, Lorraine Tarabay took over the role of chairperson.[12]

The MCA is a not-for-profit, charitable organisation which receives ongoing funding and support from the NSW State Government through Arts NSW and the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council. Every year, the MCA raises approximately 70 per cent of its income from a variety of sources such as exhibitions and events, sponsorship, donations and venue hire.[13]

Architecture[]

The museum building has two wings: a main section housed in the former Maritime Services Board (MSB) building, and the newer Mordant Wing on the museum's northern end.[citation needed]

The architecture of the Museum of Contemporary Art has drawn criticism and praise from both Australian and international commentators, mainly over the buildings' contrasting facades.[14][15] The six-storey former MSB building is an example of the Inter-War Stripped Classicism[7] style of government offices of this era, with Art Deco detailing. It is clad with sandstone and carved with naval iconography. Pink granite frames its major entrances. A series of New South Wales stones, such as Wombeyan marble, were used for internal decoration.[7] The building itself is heritage listed at both the state and federal levels.[16][17]

The building's former offices were renovated into a more open space with movable walls to accommodate exhibition requirements, with some rooms left intact as archival spaces. The inadequacy of the renovated MSB building as a gallery space, including circulation and accessibility issues, prompted plans for further renovations.[18] In 1997, an international competition was launched for redesigns of the site.[19] The Japanese architectural studio SANAA won, but its plans were abandoned after site investigations revealed the archaeological remains of a colonial dockyard beneath the museum's car park.[1] Plans by Sauerbruch Hutton, winners of a 2000 competition, were also abandoned following public outcry over the proposed demolition of the MSB building.[1]

In 2002, Director Elizabeth Ann Macgregor began developing plans for an extension to the museum site. In conjunction with Simon Mordant, investment banker and Chairman of the Museum of Contemporary Art from 2007, Macgregor selected Sydney-based architect Sam Marshall for the project.[19] The $53 million cost came from several sources.[18] Mordant donated $15 million, with an additional $13 million from the federal and NSW State Governments. Private benefactors donated another $7.5 million.[20]

Construction began in 2010 as a collaborative work between Marshall and the NSW Government's Architect Office; it was completed in March 2012. A new wing, named after Simon Mordant, was constructed in a Cubist architectural style, appearing as a series of overlapping white, black, and brown boxes that contrasts with the Art Deco MSB building.[14] The wing added 4,500 square metres (48,000 sq ft) in floor space,[19] including a café, sculpture terrace and two harbour-side function venues. The renovations additionally supplied the new National Centre for Creative Learning with multimedia and digital studios, as well as a 117-seat lecture theatre.[1] The dual entranceways of the new museum wing additionally connected George Street and Circular Quay for the first time.[20]

Collections[]

What is now the museum's main collection emerged from the Power Collection in the original founding of the museum. The museum's initial acquisitions policy, based on the will of John Power, sought to acquire mainly international contemporary art whilst only "very occasionally" purchasing Australian art as complementary to its foreign collection.[21] From 2002, the museum has shifted to increase its emphasis on Australian artists and currently holds over 4,500 works.[22]

The Ramingining Collection[]

The Ramingining collection, purchased in 1984–1985, comprises more than 250 works by over 80 Yolŋu artists.[23] The collection contains bark paintings, woven objects, sculpture and cultural objects such as spears and tools.[24][23] The collection was originally acquired by the University of Sydney for the Power Collection following the 1984 exhibition Objects and Representations from Ramingining, curated by Djon Mundine for the Power Gallery of Contemporary Art.[23][25]

In 1996, the Ramingining Collection was displayed at the MCA. The Native Born: Objects and Representations from Ramingining, Arnhem Land., its first exhibition, was curated by Djon Mundine.[23] Four years later, it was displayed in the entrance galleries in the Yolnu Science: Objects and Representations from Ramingining, Arnhem Land exhibition to coincide with the Olympics,[23] curated by Djon Mundine and Linda Michael.[23]

The Maningrida Collection[]

Formed by Diane Moon in 1990,[26] the Maningrida Collection contains 560 works from the Maningrida community in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.[24] Ownership of the pieces belongs to the Maningrida people, with the collection subject to a unique cultural agreement between the museum and the community.[24] The collection includes sculpture, woven objects and bark paintings.[24] The museum works with Indigenous researchers, curators and artists and Maningrida Arts and Culture to document and research objects within the collection.[27] The cultural agreement between both parties is renegotiated regularly to ensure a positive relationship.[28]

In 2018, the MCA in association with Maningrida Arts and Culture held the John Mawurndjul: I am the old and new exhibition of works by John Mawurndjul.[28] More than 130,000 people attended;[28] it was additionally displayed at eight regional Australian galleries.[29] Two works by John Mawurndjul, Nawarramulmul (Shooting Star Spirit, 1988) and Ngalyod (Female Rainbow Serpent, 1988), were the first artworks acquired for the dedicated MCA collection in 1989.[29]

The Arnott's Collection[]

The Arnott's Collection was formed following the donation of 285 bark paintings by the Arnott family in 1993.[30] The collection featured in Djon Mundine's 2008 exhibition They are meditating: bark paintings from the MCA's Arnott's Collection.[31]

The Smorgon Collection[]

The Smorgon Collection was donated to the MCA in 1995 by philanthropists Loti and Victor Smorgon.[24] It contains 149 contemporary Australian works[24] from the 1980s and 1990s.[32] In 2012, a donation by Loti went to build a sculpture terrace on the museum's fourth level, subsequently named for her.[33]

Selected temporary exhibitions[]

- Pipilotti Rist – ‘Sip My Ocean’ (2018)

- Grayson Perry – ‘My Pretty Little Art Career’ (2016)

- Yoko Ono – ‘War is Over! (if you want it)’ (2013)

- Anish Kapoor (2013)

- Annie Leibovitz – ‘A Photographer’s Life 1990–2005’ (2011)

- Yayoi Kusama – ‘Mirrored Years’ (2009)

- Patricia Piccinini – ‘Call of the Wild’ (2002)

- Cindy Sherman – ‘Retrospective’ (1999)

- Marina Abramović – ‘objects, performance, video, sound’ (1998)

- Keith Haring (1996)

- Andy Warhol – 'Portraits’ (1994)

Primavera Exhibition[]

Primavera: The Belinda Jackson Exhibit, Australia's longest running exhibition, has been staged annually since 1992 in honour of Edward and Cynthia Jackson's daughter Belinda, a jewellery maker.[34] It exhibits the work of Australian artists aged 35 or younger for several summer months.[35] Primavera provides the opportunity for artists not yet established to have their work displayed in a large institution.[36] The exhibition often utilises guest curators, although curatorial staff from the Museum of Contemporary Art have also worked on past Primaveras.[37] Each yearly exhibit is designed with a unique theme. In 2011, as a result of the museum renovations, the Primavera exhibit was held off-site. Artworks from the exhibition were displayed in various places around the museum and throughout The Rocks area of Sydney.[37]

Tate x MCA Collaboration[]

In 2015, a five-year collaborative project was announced between the Tate Galleries of Britain and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia for the mutual acquisition of contemporary Australian artworks.[38] The project is aimed at increasing the reputation of Australian art internationally. Funded by a $2.75 million donation from the Qantas Foundation, the galleries have acquired 23 pieces by 16 major Australian artists, many of which have been displayed at both institutions.[39]

The National[]

The National: New Australian Art exhibition was launched in 2017 and held jointly at the Art Gallery of NSW, Carriageworks and the MCA. It was designed to "reflect the diversity of cultural, political and social perspectives that preoccupy [Australian] artists". The National was designed in three iterations, with the later ones in 2019 and 2021, exhibiting the work of 150 Australian artists.[40]

Programs[]

The Museum of Contemporary Art holds a number of public programs over its calendar year, including an Indigenous learning program and an 'Art + Dementia' research program.[41]

The Bella program[]

The Bella program was established in 1993[42] by patrons Edward and Cynthia Jackson and the Jackson family.[43] The program season previously coincided with the Primavera exhibition, however the addition of the National Centre for Creative Learning and funding from private benefactors in 2012 allowed for the Bella program to be run year-round. Tailored for young people[44] the program focuses on issues of access to contemporary art for people with disabilities, and socially and financially disadvantaged individuals. The program offers sessions in the galleries and hands-on workshops.[43]

In 2011, the Bella program collaborated with Good Vibrations, a touring interactive art project for young people and adults with disabilities.[43] The caravan, designed by artists Bruce Odland and Michael Luck Schneider,[44] is fitted with technical devices that create sensory responses to sights, sounds and vibrations.[43]

The dedicated Bella Room was installed in the National Centre for Creative learning in 2012. Each year a new artist is commissioned to produce a work in the Bella Room concerned with a different type of disability.[44] The room offers a sensory environment in which students, led by artist educators, can interact with art.[42]

Genext[]

'GENEXT' has been held since 2005 as an public engagement program aimed at young people aged from 12 to 18, run by MCA's Youth Committee. GENEXT is an after-hours program that includes activities such as live music, discussions, and art workshops.[45] It is held four times annually, and included over 16,000 participants over the course of its first ten years of operation.[46]

In collaboration with the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Museum of Contemporary Art takes part in the Sydney Festival and the Biennale of Sydney, an event held partially online in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[47]

MCA Zine Fair[]

The annual MCA Zine Fair, first held in 2008, is organised in conjunction with the Sydney Writers' Festival. Held on the front lawn of the MCA, the free fair features over 50 stalls of new and established zine artists.[48]

The Artful: Art and Dementia[]

In 2016, The Artful: Art and Dementia program was launched as a three-year research collaboration between the MCA, the Brain and Mind Centre, the University of Sydney and Dementia Australia with the goal of establishing a link between art and enhanced neuroplasticity.[49] The program continues annually.[citation needed]

The six-week program includes a tour of selected works throughout the museum, weekly two-hour creative art making sessions with trained artist-educators and an 'Artful at home' package containing materials for art making at home. The final week of the program is an exhibition session, in which participant's friends and family are invited to view their art.[49] In 2020, the program launched an online digital toolkit to enable offsite participation.[50]

Access and environs[]

The nearest station to the MCA is Circular Quay station, Circular Quay. Paid parking is available within five minutes walk of the museum.

Transport connections[]

| Service | Station/Stop | Lines/Routes served | Distance

from the Museum of Contemporary Art |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sydney Buses |

Circular Quay, Young St, Stand D |

333, 333N, 392, 394, 396, 397, 399, L94 | 400 metres (5-minute walk)[51] |

| Circular Quay, Alfred St, Stand A |

304, 339, 343, 373, 374, 377 | 400 metres (5-minute walk)[52] | |

| Argyle Pl at Lower Fort St | 311 | 400 metres (6-minute walk)[53] | |

| Circular Quay, Alfred St, Stand B |

333, 392, 394, 396, 397, 399, L94, X94, X97 | 450 metres (6-minute walk)[54] | |

| Exchange Square, Bridge St |

115 | 500 metres (6-minute walk)[55] | |

| Sydney Light Rail |

Circular Quay |

L2 ■, L3 ■ | 280 metres (3-minute walk)[56] |

| Bridge St |

L2 ■, L3 ■ | 550 metres (7-minute walk)[57] | |

| Wynyard |

L2 ■, L3 ■ | 850 metres (11-minute walk)[58] | |

| Sydney Trains |

Circular Quay |

T2 ■, T3 ■, T4 ■, T7 ■, T8 ■ | 300 metres (4-minute walk)[59] |

| Wynyard |

Central Coast and Newcastle Line ■, T1 ■, T2 ■, | 700 metres (9-minute walk)[60] | |

| Sydney Ferries |

Circular Quay ferry wharf |

F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, F7, F8, F9 | 300 metres (4-minute walk)[61] |

See also[]

- Architecture of Sydney

- List of art museums and galleries in Australia

- List of museums in Sydney

- Sydney Cove West Archaeological Precinct

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Craswell, Penny (12 April 2012). "The reimagined Museum of Contemporary Art". ArchitectureAU. Architecture Media Pty Ltd. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Visitor Figures 2016" (PDF). The Art Newspaper Review. April 2017. p. 14. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art". Sydney Architecture. n.d. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art to reopen in 2012". World Interior Design Network. Australia. 26 May 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Brownell, Ginanne (20 March 2012). "A Makeover for Contemporary Art in Sydney". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Kneen, Dale (Summer 2012). "Starchitects in Our Eyes". High Life. British Airways: 16–17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Architects, Tanner (October 2008). "Museum of Contemporary Art, Circular Quay: Redevelopment and Expansion Heritage Impacts Statement". NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Archibald, J. F; Haynes, John (11 January 1969). "Art bequests (11 January 1969)". The Bulletin. 091 (4635). Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Murphy, Bernice (1993). Museum of contemporary art : vision & context. Sydney: Museum of contemporary art. p. 105. ISBN 976-8097-22-1. OCLC 443910300.

- ^ Stephensen, PR (1966). The History & Description of Sydney Harbour. Rigby. p. 160. ISBN 0589502433.

- ^ "The MCA's new Mordant Wing". Artist Profile. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Kembrey, Melanie (30 April 2020). "Lorraine Tarabay named next chair of Museum of Contemporary Art". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ "About the MCA". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lines of division: The new MCA in Sydney". Australian Design Review. 8 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Aston, Heath (3 March 2012). "MCA's chequered reception". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Heritage and Conservation Register". www.shfa.nsw.gov.au. Property NSW. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Maritime Services Board Building (former), 136–140 George St, The Rocks, NSW, Australia (Place ID 102747)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. 21 October 1980. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brownell, Ginanne (20 March 2012). "A Makeover for Contemporary Art in Sydney". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Humphries, Oscar (May 2012). "A New Horizon: the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney reopened in March following an 18-month redevelopment. Its transformation further enlivens the cultural landscape of Australia, and is the latest development in the increasingly international profile of Australian art". Apollo. 175: 62–65 – via Gale Academic Onefile.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Phillips, Juanita (May 2010). "Major Facelift to Make Sydney's MCA World Class: Work Will Begin next Month on a Major Upgrade of Sydney's Museum of Contemporary Art". ABC News NSW. Anne Maria Nicholson, Anthony Albanese, Kristina Keneally, and Elizabeth Ann Macgregor. doi:10.3316/tvnews.ten20101801895 (inactive 24 July 2021). Retrieved 28 August 2021.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2021 (link)

- ^ Murphy, Bernice (1993). Museum of contemporary art : vision & context. Sydney: Museum of contemporary art. p. 93. ISBN 976-8097-22-1. OCLC 443910300.

- ^ "The 'outsider' steering the MCA through the crisis". Australian Financial Review. 30 April 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Liberiou, Katrina (2021). "Crossing Paths with the Ramingining Collection". In Conway, Rebecca (ed.). Djalkiri: Yolŋu Art, Collaborations and Collections. Sydney: Sydney University Press. pp. 202–211. ISBN 9781743327272.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Wallace, Sue‐anne (2000). "From campus to city: university museums in Australia". Museum International. 52 (3): 32–37. doi:10.1111/1468-0033.00270. ISSN 1350-0775. S2CID 145320336. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Jagodzińska, Katarzyna (2018). "Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney". Art Museums in Australia (PDF). Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press. p. 214. ISBN 9788323343363. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Australia, National Museum of (8 June 2011). "Understanding Museums – Transforming culture". nma.gov.au. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation Maningrida (2020). "Maningrida Arts & Culture: Annual Report 2019–20" (PDF). Maningrida Arts & Culture. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation Maningrida (2019). "Maningrida Arts & Culture: Annual Report 2018–19" (PDF). Maningrida Arts and Culture. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Charles Darwin University Australia (2021). "Charles Darwin University Art Gallery presents John Mawurndjul: I am the old and the new" (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Eccles, Jeremy (March 2011). "Bardayal 'Lofty' Nadjamerrek AO". Art Monthly Australia. 237: 26–29. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via Informit.

- ^ Sprague, Quentin (2016). "Making in translation: the intercultural broker in indigenous Australian art". Doctor of Philosophy Thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong: 1–353. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Bojic, Zoja (2012). "Art curatorship within and outside museum". ICOM SEE Singidunum University CIK: 1–93. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "MCA Commemorates Arts Benefactor Loti Smorgon on Art.Base.BASE". Art.Base (Press release). Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. 21 August 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Michael (December 2016). "A Transfer of Stimulus and Creativity: 25 Years of 'Primavera'". Art Monthly Australasia. 295: 54–65. ISSN 1033-4025 – via Informit.

- ^ Fortescue, Elizabeth (15 December 2016). "Cynthia Jackson looks back on 25 years of the Primavera exhibition, which celebrates her daughter's life". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ O'Toole, Phil (December 1997). "Primavera: The Belinda Jackson Exhibition of Young Artists". Eyeline. 35: 37–38. ISSN 0818-8734 – via Informit.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Novak, Karolina (2013). Marianne Hulsbosch. "Examining Museum Education Kits Using a Cultural Capital Lens: The Positioning of Visual Arts Teachers and Their Students Within Museum Education Kits". The International Journal of the Inclusive Museum. 5 (3): 37–49. doi:10.18848/1835-2014/CGP/v05i03/58323. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Tate (24 May 2019). "MCA, Tate and Qantas announce three new Australian artwork acquisitions – Press Release" (Press release). Tate. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Eccles, Jeremy (January 2017). "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia/Tate Project". Eyeline. 86: 62–65. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via Informit.

- ^ Yip, Andrew (2017). "The National 2017: New Australian Art: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Carriageworks, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 30 March – 16 July 2017". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art. 17: 256–260. doi:10.1080/14434318.2017.1450065. S2CID 194997479 – via Taylor and Francis Online.

- ^ "Artful: Art and Dementia report | MCA Australia | MCA Australia". www.mca.com.au. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cann, Richard (May 2012). "MCA brings art education into the digital age". Education. 93: 17. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d McMillen, Rebecca (2011). "Diverse audiences: disability access and the art museum". Pacific Journal. 6: 65–73. hdl:11418/510. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via Fresno Pacific University.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McDonald, Gay (2012). "Engaging art museum audiences: the MCA's National Centre for Creative Learning". Art and Australia. 49: 403–405 – via Gale Academic Onefile.

- ^ Boyce, Brooke (2018). "Evaluating with the next Generation". Patternmakers.

- ^ "Genext Turns 10! on Art.Base.BASE". Art.Base (Press release). Museum of Contemporary Art. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ "The End of the Art World as We Know It". Hyperallergic. 4 April 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Cox, Debbie (August 2009). Marjorie Currie. "Zooming into the world of comics, graphic novels and zines". National Library of Australia Gateways. 100. Retrieved 28 August 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Howarth, Lynne C. (2019). "Dementia Friendly Memory Institutions: Designing a Future for Remembering". The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion. 4: 20–41.

- ^ Morris, Linda (26 February 2020). "Artpacks designed to empower dementia sufferers become national tool". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Young St, Stand D". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Young St, Stand D. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Alfred St, Stand A". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Alfred St, Stand A. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Argyle Pl at Lower Fort St". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Argyle Pl at Lower Fort St. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Alfred St, Stand B". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Alfred St, Stand B. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Exchange Square, Bridge St". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Exchange Square, Bridge St. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Bridge Street". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Bridge Street. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Wynyard". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Wynyard. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Wynyard". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Wynyard. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Wharf 4". Museum of Contemporary Art Australia to Circular Quay, Wharf 4. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. |

- Museum of Contemporary Art official website

- Museum of Contemporary Art Artabase page[dead link]

- "Commissariat Stores". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]. (Building that formerly occupied site, demolished 1939.)

- Contemporary art galleries in Australia

- Art Deco architecture in Sydney

- Art museums and galleries in Sydney

- Art museums established in 1991

- 1991 establishments in Australia

- The Rocks, New South Wales

- New South Wales places listed on the defunct Register of the National Estate

- Sydney central business district