Naval history of Japan

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

The naval history of Japan began with early interactions with states on the Asian continent in the 3rd century BCE during the Yayoi period. It reached a pre-modern peak of activity during the 16th century, a time of cultural exchange with European powers and extensive trade with the Asian continent. After over two centuries of self-imposed seclusion under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan's naval technologies became outdated compared to Western navies. The country was forced to abandon its maritime restrictions by American intervention with the Perry Expedition in 1854. This and other events led to the Meiji Restoration, a period of frantic modernization and industrialization accompanied by the re-ascendance of the Emperor's rule and colonialism with the Empire of Japan. Japan became the first industrialized Asian country in 1868, by 1920 the Imperial Japanese Navy was the third largest navy in the world and arguably the most modern at the brink of World War II.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had a history of successes, sometimes against much more powerful foes as in the 1894–1895 Sino-Japanese War, the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War, and early naval battles during World War II. In 1945, towards the end of the conflict, the navy was almost completely destroyed by the United States Navy. Japan's current navy is a branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) called the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF). In 2015, the JMSDF was ranked by Credit Suisse as the 4th most powerful military in the world.[1] However, it is still denied any offensive role by the nation's post-war Constitution and public opinion.

Prehistory[]

Japan was connected to the Asian continent via land bridges during the glacial maximum of the last Ice Age around 20,000 BCE.[2] This allowed for the transmission of flora and fauna, including the establishment of the Jōmon culture. The land bridges disappeared in the Jōmon period around 10,000 BCE.[2] After that period however, Japan became an isolated island territory, depending entirely on sporadic naval activity for its interactions with the continent. The shortest seapath to the continent (besides the inhospitable northern path from Hokkaidō to Sakhalin) then involved two stretches of open water about 50 kilometers wide, between the Korean peninsula and the island of Tsushima, and then from Tsushima to the major island of Kyūshū.

Various influences have also been suggested from the direction of the Pacific Ocean, as various cultural and even genetic traits seem to point to partial Pacific origins, possibly in relation with the Austronesian expansion.

Early historical period[]

Ambassadorial visits to Japan by the later Northern Chinese dynasties Wei and Jin (Encounters of the Eastern Barbarians, Wei Chronicles) recorded that some Japanese people claimed to be descendants of Taibo of Wu, refugees after the fall of the Wu state in the 5th century BCE. History books do have records of Wu Taibo sending 4000 males and 4000 females to Japan.[5]

Yayoi Period[]

The first major naval contacts occurred in the Yayoi period in the 3rd century BCE, when rice-farming and metallurgy were introduced, from the continent.

The 14 AD incursion of Silla (新羅, Shiragi in Japanese), one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, is the earliest Japanese military action recorded in Samguk Sagi. According to that record, Wa (the proto-Japanese nation) sent one hundred ships and led an incursion on the coastal area of Silla before being driven off.

Yamato Period[]

During the Yamato period, Japan had intense naval interaction with the Asian continent, largely centered around diplomacy and trade with China, the Korean kingdoms, and other continental states, since at latest the beginning of the Kofun period in the 3rd century. According to a mythological account in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, Empress Jingū is claimed to have invaded Korea in the 3rd century, and to have returned victorious after three years. Whether a Japanese political entity actually ruled a part of Korea in ancient times is debated, but considered unlikely for that time period.[3]

Other than the expedition of Empress Jingū, battle of Hakusukinoe (白村江), one of the earliest historical events in Japan's naval history took place in 663. Japan sent 32,000 troops and possibly as many as 1,000 ships to Korea to support the declining Baekje kingdom (百済国; contemporary records suggest that Baekje and Yamato Japan were allies, and that their royal/imperial families were possibly related) against Silla and Tang-dynasty China. They were defeated by the T'ang-Silla combined force.

Medieval period[]

Naval battles of a very large scale, fought between Japanese clans and involving more than 1000 warships, are recorded from the 12th century. The decisive battle of the Genpei War, and one of the most famous and important naval battles in pre-modern Japanese history, was the 1185 battle of Dan-no-ura, which was fought between the fleets of the Minamoto and Taira clans. These battles consisted first of long-range archery exchanges, then giving way to hand-to-hand combat with swords and daggers. Ships were used largely as floating platforms for what were largely land-based melee tactics.

Mongol invasions (1274–1281)[]

The first major references to Japanese naval actions against other Asian powers occur in the accounts of the Mongol invasions of Japan by Kublai Khan in 1281. Japan had no navy which could seriously challenge the Mongol navy, so most of the action took place on Japanese land. Groups of samurai, transported on small coastal boats, are recorded to have boarded, taken over and burned several ships of the Mongol navy.

Wakō piracy (13th–16th century)[]

During the following centuries, wakō pirates actively plundered the coast of the Chinese Empire. Though the term wakō translates directly to "Japanese pirates", Japanese were far from the only sailors to harass shipping and ports in China and other parts of Asia in this period, and the term thus more accurately includes non-Japanese pirates as well. The first raid by wakō on record occurred in the summer of 1223, on the south coast of Goryeo. At the peak of wakō activity around the end of the 14th century, fleets of 300 to 500 ships, transporting several hundred horsemen and several thousand soldiers, would raid the coast of China[6]. For the next half-century, sailing principally from Iki Island and Tsushima, they engulfed coastal regions of the southern half of Goryeo. Between 1376 and 1385, no fewer than 174 instances of pirate raids were recorded in Korea. However, when Joseon dynasty was founded in Korea, wakō took a massive hit in one of their main homeland of Tsushima during the Ōei Invasion. The peak of wakō activity was during the 1550s, when tens of thousands of pirates raided the Chinese coast in what is called the Jiajing wakō raids, but the wakō at this time were mostly Chinese. Wakō piracy ended for the most part in the 1580s with its interdiction by Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Official trading missions, such as the Tenryūji-bune, were also sent to China around 1341.

Sengoku period (15th–16th century)[]

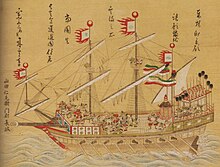

Various daimyō clans undertook major naval building efforts in the 16th century, during the Sengoku period, when feudal rulers vying for supremacy built vast coastal navies of several hundred ships. The largest of these ships were called atakebune. Around that time, Japan seems to have developed one of the first ironclad warships in history, when Oda Nobunaga, a Japanese daimyō, had six iron-covered Ō-atakebune ("Great Atakebune") made in 1576 [7]. These ships were called tekkōsen (鉄甲船), literally "iron armored ships", and were armed with multiple cannons and large caliber rifles to defeat the large, but all wooden, vessels of the enemy. With these ships, Nobunaga defeated the Mōri clan navy at the mouth of the Kizu River, near Osaka in 1578, and began a successful naval blockade. The Ō-atakebune are regarded as floating fortresses rather than true warships, however, and were only used in coastal actions.

European contacts[]

This section may contain material unrelated or insufficiently related to its topic. (August 2016) |

The first Europeans reached Japan in 1543 on Chinese junks, and Portuguese ships started to arrive in Japan soon after. At that time, there was already trade exchanges between Portugal and Goa (since around 1515), consisting in 3 to 4 carracks leaving Lisbon with silver to purchase cotton and spices in India. Out of these, only one carrack went on to China in order to purchase silk, also in exchange for Portuguese silver. Accordingly, the cargo of the first Portuguese ships (usually about 4 smaller-sized ships every year) arriving in Japan almost entirely consisted of Chinese goods (silk, porcelain). The Japanese were very much looking forward to acquiring such goods, but had been prohibited from any contacts with by the Emperor of China, as a punishment for wakō pirate raids. The Portuguese (who were called Nanban, lit. Southern Barbarians) therefore found the opportunity to act as intermediaries in Asian trade.

From the time of the acquisition of Macau in 1557, and their formal recognition as trade partners by the Chinese, the Portuguese started to regulate trade to Japan, by selling to the highest bidder the annual "captaincy" () to Japan, in effect conferring exclusive trading rights for a single carrack bound for Japan every year. The carracks were very large ships, usually between 1000 and 1500 tons, about double or triple the size of a large galleon or junk.

That trade continued with few interruptions until 1638, when it was prohibited on the grounds that the priests and missionaries associated with the Portuguese traders were perceived as posing a threat to the shogunate's power and the nation's stability.

Portuguese trade was progressively more and more challenged by Chinese smugglers, Japanese Red Seal Ships from around 1592 (about ten ships every year), Spanish ships from Manila from around 1600 (about one ship a year), the Dutch from 1609, and the English from 1613 (about one ship per year). Some Japanese are known to have travelled abroad on foreign ships as well, such as Christopher and Cosmas who crossed the Pacific on a Spanish galleon as early as 1587, and then sailed to Europe with Thomas Cavendish.

The Dutch, who, rather than Nanban were called Kōmō (紅毛), lit. "Red Hair" by the Japanese, first arrived in Japan in 1600, on board the Liefde. Their pilot was William Adams, the first Englishman to reach Japan. In 1605, two of the Liefde's crew were sent to Pattani by Tokugawa Ieyasu, to invite Dutch trade to Japan. The head of the Pattani Dutch trading post, , refused on the grounds that he was too busy dealing with Portuguese opposition in Southeast Asia. In 1609, however, the Dutchman Jacques Specx arrived with two ships in Hirado, and through Adams obtained trading privileges from Ieyasu.

The Dutch also engaged in piracy and naval combat to weaken Portuguese and Spanish shipping in the Pacific, and ultimately became the only Westerners to be allowed access to Japan. For two centuries beginning in 1638, they were restricted to the island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor.

Invasions of Korea and the Ryūkyūs[]

In 1592 and again in 1598, Toyotomi Hideyoshi organized invasions of Korea using some 9,200 ships.[4] From the beginning of the War in 1592, the supreme commander of Hideyoshi's fleet was Kuki Yoshitaka, whose flagship was the 33 meter-long Nihonmaru. Subordinate commanders included Wakisaka Yasuharu and Katō Yoshiaki. After their experience in the Ōei Invasion and other operations against Japanese pirates, the Chinese and Korean navies were more skilled than the Japanese. They relied throughout upon large numbers of smaller ships whose crews would attempt to board the enemy. Boarding was the main tactic of almost all navies until the modern era, and Japanese samurai excelled in close combat. The Japanese commonly used many light, swift, boarding ships called Kobaya in an array that resembled a rapid school of fish following the leading boat. This tactic's advantage was that once they succeeded in boarding one ship, they could hop aboard other enemy ships in the vicinity, in a wildfire fashion.

Japanese ships at the time were built with wooden planks and steel nails, which rusted in seawater after some time in service. The ships were built in a curved pentagonal shape with light wood for maximum speeds for their boarding tactics, but it undermined their capability to quickly change direction. Also, they were somewhat susceptible to capsizing in choppy seas and seastorms. The hulls of Japanese ships were not strong enough to support the weight and recoil of cannons. Rarely did Japanese ships have cannons, and those that did usually hung them from overhead beams with ropes and cloth. Instead, the Japanese relied heavily on their muskets and blades.

The Korean Navy attacked a Japanese transportation fleet effectively and caused extensive damage. Won Gyun and Yi Sun-sin at the Battle of Okpo has destroyed the Japanese convoy, and their failure enabled Korean resistance in Jeolla province, in the south-east of Korea, to continue. Wakisaka Yasuharu was ordered to dispatch a 1,200 man navy during the Keicho Invasion and annihilated the invading Korean navy led by Won Kyun during a counterattack in July 1597 (Battle of Chilcheollyang). Korean Admiral Yi Eokgi and Won Gyun of Korea were killed in this combat. Hansan Island was occupied by Japan, consolidating the Japanese hold on the west coast of Korea. To prevent Japan from invading China by way of the Korean peninsula west coast, China sent naval forces.[5]

In August 1597, the Japanese Navy was ordered to occupy the Jeolla.[6] After the Joseon Navy gave a damage Japan Navy in the Battle of Myeongnyang, withdrew North of the Korean peninsula. Jeolla was finally occupied by the Japanese Navy, and the Gang Hang became the captive. Remnants of the Korean navy led by Yi Sun-sin joined the Ming Chinese fleet under Chen Lin's forces and continued to attack Japanese supply lines. Towards the end of the war, as the remaining Japanese tried to withdraw from Korea, they were beset by Korean and Chinese forces.[7] To rescue his comrades, Shimazu Yoshihiro attacked the allied fleet. At the Battle of Noryang, Shimazu defeated Chinese general Chen Lin. And the Japanese army succeeded in escape from the Korean Peninsula[8][9] Yi Sun-sin was killed in this action.[10]

Japan's failure to gain control of the sea, and their resulting difficulty in resupplying troops on land, was one of the major reasons for the invasion's ultimate failure. After the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the main proponent of the invasion, the Japanese ceased attacks on Korea.

Invasion of the Ryūkyūs[]

In 1609, Shimazu Tadatsune, Lord of Satsuma, invaded the southern islands of Ryūkyū (modern Okinawa) with a fleet of 13 junks and 2,500 samurai, thereby establishing suzerainty over the islands. They faced little opposition from the Ryukyuans, who lacked any significant military capabilities, and who were ordered by King Shō Nei to surrender peacefully rather than suffer the loss of precious lives.[11]

Oceanic trade (16th–17th century)[]

Japan built her first large ocean-going warships at the beginning of the 17th century, following contacts with the Western nations during the Nanban trade period.

William Adams[]

In 1604, Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu ordered William Adams and his companions to build Japan's first Western-style sailing ship at Itō, on the east coast of the Izu Peninsula. An 80-ton vessel was completed and the shōgun ordered a larger ship, 120 tons, to be built the following year (both were slightly smaller than the Liefde, the ship in which William Adams came to Japan, which was 150 tons). According to Adams, Ieyasu "came aboard to see it, and the sight whereof gave him great content". The ship, named San Buena Ventura, was lent to shipwrecked Spanish sailors for their return to Mexico in 1610.

Hasekura Tsunenaga[]

In 1613, the daimyō of Sendai, in agreement with the Tokugawa shogunate, built Date Maru, a 500-ton galleon-type ship that transported a Japanese embassy to the Americas, and then continued to Europe.

Red Seal ships[]

From 1604, about 350 Red seal ships, usually armed and incorporating some Western technologies, were authorized by the shogunate, mainly for Southeast Asian trade. Japanese ships and samurai helped in the defense of Malacca on the side of the Portuguese against the Dutch Admiral Cornelis Matelief in 1606. Several armed ships of the Japanese adventurer Yamada Nagamasa would play a military role in the wars and court politics of Siam. William Adams, who participated in the Red Seal ship trade, would comment that "the people of this land (Japan) are very stout seamen".

Planned invasion of the Philippines[]

The Tokugawa shogunate had, for some time, planned to invade the Philippines in order to eradicate Spanish expansionism in Asia, and its support of Christians within Japan. In November 1637 it notified Nicolas Couckebacker, the head of the Dutch East India Company in Japan, of its intentions. About 10,000 samurai were prepared for the expedition, and the Dutch agreed to provide four warships and two yachts to support the Japanese ships against Spanish galleons. The plans were cancelled at the last minute with the advent of the Christian Shimabara Rebellion in Japan in December 1637.[12] [13]

Seclusion (1640–1840)[]

The Dutch's cooperation on these, and other matters, would help ensure they were the only Westerners allowed in Japan for the next two centuries. Following these events, the shogunate imposed a system of maritime restrictions (海禁, kaikin), which forbade contacts with foreigners outside of designated channels and areas, banned Christianity, and prohibited the construction of ocean-going ships on pain of death. The size of ships was restricted by law, and design specifications limiting seaworthiness (such as the provision for a gaping hole in the aft of the hull) were implemented. Sailors who happened to be stranded in foreign countries were prohibited from returning to Japan on pain of death.

A tiny Dutch delegation in Dejima, Nagasaki was the only allowed contact with the West, from which the Japanese were kept partly informed of western scientific and technological advances, establishing a body of knowledge known as Rangaku. Extensive contacts with Korea and China were maintained through the Tsushima Domain, the Ryūkyū Kingdom under Satsuma's dominion, and the trading posts at Nagasaki. The Matsumae Domain on Hokkaidō managed contacts with the native Ainu peoples, and with Imperial Russia.

Many isolated attempts to end Japan's seclusion were made by expanding Western powers during the 19th century. American, Russian and French ships all attempted to engage in relationship with Japan, but were rejected.

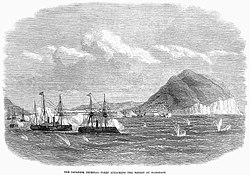

These largely unsuccessful attempts continued until, on July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the U.S. Navy with four warships: Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga, and Susquehanna steamed into the Bay of Edo (Tokyo) and displayed the threatening power of his ships' Paixhans guns. He demanded that Japan open to trade with the West. These ships became known as the kurofune, or Black Ships.

Barely one month after Perry, the Russian Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin arrived in Nagasaki on August 12, 1853. He made a demonstration of a steam engine on his ship the Pallada, which led to Japan's first manufacture of a steam engine, created by Tanaka Hisashige.

The following year, Perry returned with seven ships and forced the shōgun to sign the "Treaty of Peace and Amity", establishing formal diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States, known as the Convention of Kanagawa (March 31, 1854). Within five years Japan had signed similar treaties with other western countries. The Harris Treaty was signed with the United States on July 29, 1858. These treaties were widely regarded by Japanese intellectuals as unequal, having been forced on Japan through gunboat diplomacy, and as a sign of the West's desire to incorporate Japan into the imperialism that had been taking hold of the continent. Among other measures, they gave the Western nations unequivocal control of tariffs on imports and the right of extraterritoriality to all their visiting nationals. They would remain a sticking point in Japan's relations with the West up to the start of the 20th century.

Modernization: Bakumatsu period (1853–1868)[]

The study of Western shipbuilding techniques resumed in the 1840s. This process intensified along with the increased activity of Western shipping along the coasts of Japan, due to the China trade and the development of whaling.

From 1852, the government of the shōgun (the Late Tokugawa shogunate or "Bakumatsu") was warned by the Netherlands of the plans of Commodore Perry. Three months after Perry's first visit in 1853, the Bakufu cancelled the law prohibiting the construction of large ships (大船建造禁止令), and started organizing the construction of a fleet of Western-style sail warships, such as the Hōō Maru, the or the Asahi Maru, usually asking each fief to build their own modern ships. These ships were built using Dutch sailing manuals, and the know-how of a few returnees from the West, such as Nakahama Manjirō. Also with the help of Nakahama Manjirō, the Satsuma fief built Japan's first steam ship, the Unkoumaru (雲行丸) in 1855.[14] The Bakufu also established defensive coastal fortifications, such as at Odaiba.

[]

As soon as Japan agreed to open up to foreign influence, the Tokugawa shōgun government initiated an active policy of assimilation of Western naval technologies. In 1855, with Dutch assistance, the shogunate acquired its first steam warship, the Kankō Maru, which was used for training, and established the Nagasaki Naval Training Center. In 1857, it acquired its first screw-driven steam warship, the Kanrin Maru.

In 1860, the Kanrin Maru was sailed to the United States by a group of Japanese, with the assistance of a single US Navy officer John M. Brooke, to deliver the first Japanese embassy to the United States.

Naval students were sent abroad to study Western naval techniques. The Bakufu had initially planned on ordering ships and sending students to the United States, but the American Civil War led to a cancellation of plans. Instead, in 1862 the Bakufu placed its warship orders with the Netherlands and decided to send 15 trainees there. The students, led by (内田恒次郎), left Nagasaki on September 11, 1862, and arrived in Rotterdam on April 18, 1863, for a stay of 3 years. They included such figures as the future Admiral Enomoto Takeaki, (沢太郎左衛門), (赤松則良), (田口俊平), (津田真一郎) and the philosopher Nishi Amane. This started a tradition of foreign-educated future leaders such Admirals Tōgō and, later, Yamamoto.

In 1863, Japan completed her first domestically-built steam warship, the Chiyodagata, a 140-ton gunboat commissioned into the Tokugawa Navy (Japan's first steamship was the Unkoumaru -雲行丸- built by the fief of Satsuma in 1855). The ship was manufactured by the future industrial giant, Ishikawajima, thus initiating Japan's efforts to acquire and fully develop shipbuilding capabilities.

Following the humiliations at the hands of foreign navies in the Bombardment of Kagoshima in 1863, and the Battle of Shimonoseki in 1864, the shogunate stepped up efforts to modernize, relying more and more on French and British assistance. In 1865, the French naval engineer Léonce Verny was hired to build Japan's first modern naval arsenals, at Yokosuka and Nagasaki. More ships were imported, such as the Jho Sho Maru, the and the Kagoshima, all commissioned by Thomas Blake Glover and built in Aberdeen.

By the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867, the Japanese navy already possessed eight Western-style steam warships around the flagship Kaiyō Maru which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin War, under the command of Admiral Enomoto. The conflict culminated with the Naval Battle of Hakodate in 1869, Japan's first large-scale modern naval battle.

In 1869, Japan acquired its first ocean-going ironclad warship, the Kōtetsu, ordered by the Bakufu but received by the new Imperial government, barely ten years after such ships were first introduced in the West with the launch of the French La Gloire.

[]

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) (Japanese: 大日本帝国海軍) was the navy of Japan between 1868 and until 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's defeat and surrender in World War II.

From 1868, the restored Meiji Emperor continued with reforms to industrialize and militarize Japan in order to prevent it from being overwhelmed by the United States and European powers. The Imperial Japanese Navy was formally established in 1869. The new government drafted a very ambitious plan to create a Navy with 200 ships, organized into 10 fleets, but the plan was abandoned within a year due to lack of resources. Internally, domestic rebellions, and especially the Satsuma Rebellion (1877) forced the government to focus on land warfare. Naval policy, expressed by the slogan Shusei Kokubō (守勢国防, "Static Defense"), focused on coastal defenses, a standing army, and a coastal Navy, leading to a military organization under the Rikushu Kaiju (Jp:陸主海従, Army first, Navy second) principle.

During the 1870s and 1880s, the Japanese Navy remained an essentially coastal defense force, although the Meiji government continued to modernize it. In 1870 an Imperial decree determined that the British Navy should be the model for development, and the second British naval mission to Japan, the Douglas Mission (1873–79) led by Archibald Lucius Douglas laid the foundations of naval officer training and education. (See Ian Gow, 'The Douglas Mission (1873–79) and Meiji Naval Education' in J. E. Hoare ed., Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits Volume III, Japan Library 1999.) Tōgō Heihachirō was trained by the British navy.

During the 1880s, France took the lead in influence, due to its "Jeune École" doctrine favoring small, fast warships, especially cruisers and torpedo boats, against bigger units. The Meiji government issued its First Naval Expansion bill in 1882, requiring the construction of 48 warships, of which 22 were to be torpedo boats. The naval successes of the French Navy against China in the Sino-French War of 1883–85 seemed to validate the potential of torpedo boats, an approach which was also attractive to the limited resources of Japan. In 1885, the new Navy slogan became Kaikoku Nippon (海国日本, "Maritime Japan").

In 1886, the leading French Navy engineer Émile Bertin was hired for four years to reinforce the Japanese Navy, and to direct the construction of the arsenals of Kure and Sasebo. He developed the Sankeikan class of three cruisers, which are named after Three Views of Japan, featuring a single but powerful main gun, the 12.6 inch Canet gun.

This period also allowed Japan to adopt new technologies such as torpedoes, torpedo-boats and mines, which were actively promoted by the French Navy (Howe, p281). Japan acquired its first torpedoes in 1884, and established a "Torpedo Training Center" at Yokosuka in 1886.

Sino-Japanese War[]

Japan continued the modernization of its navy, especially as China was also building a powerful modern fleet with foreign, especially German, assistance, and the pressure was building between the two countries to take control of Korea. The Sino-Japanese war was officially declared on August 1, 1894, though some naval fighting had already taken place.

The Japanese navy devastated Qing's northern fleet off the mouth of the Yalu River at the Battle of Yalu River on September 17, 1894, in which the Chinese fleet lost 8 out of 12 warships. Although Japan turned out victorious, the two large German-made battleships of the Chinese Navy remained almost impervious to Japanese guns, highlighting the need for bigger capital ships in the Japanese Navy (the Ting Yuan was finally sunk by torpedoes, and the Chen-Yuan was captured with little damage). The next step of the Imperial Japanese Navy's expansion would thus involve a combination of heavily armed large warships, with smaller and innovative offensive units permitting aggressive tactics.

The Imperial Japanese Navy further intervened in China in 1900, by participating together with Western Powers to the suppression of the Chinese Boxer Rebellion. The Navy supplied the largest number of warships (18, out of a total of 50 warships), and delivered the largest contingent of Army and Navy troops among the intervening nations (20,840 soldiers, out of total of 54,000).

Russo-Japanese War[]

Following the First Sino-Japanese War, and the humiliation of the forced return of the Liaotung peninsula to China under Russian pressure (the "Triple Intervention"), Japan began to build up its military strength in preparation for further confrontations. Japan promulgated a ten-year naval build-up program, under the slogan "Perseverance and determination" (Jp:臥薪嘗胆, Gashinshoutan), in which it commissioned 109 warships, for a total of 200,000 tons, and increased its Navy personnel from 15,100 to 40,800.

These dispositions culminated with the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). The Japanese battleship Mikasa was the flagship of Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō. At the Battle of Tsushima, the Mikasa led the combined Japanese fleet into what has been called "the most decisive naval battle in history".[8] The Russian fleet was almost completely annihilated: out of 38 Russian ships, 21 were sunk, 7 captured, 6 disarmed, 4,545 Russian servicemen died and 6,106 were taken prisoner. On the other hand, the Japanese only lost 117 men and 3 torpedo boats.

World War II[]

In the years before World War II the IJN began to structure itself specifically to fight the United States. A long stretch of militaristic expansion and the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 had alienated the United States, and the country was seen as a rival of Japan.

To achieve Japan’s expansionist policies, the Imperial Japanese Navy also had to fight off the largest navies in the world (The 1922 Washington Naval Treaty allotted a 5/5/3 ratio for the navies of Great Britain, the United States and Japan). She was therefore numerically inferior and her industrial base for expansion was limited (in particular compared to the United States). Her battle tactics therefore tended to rely on technical superiority (fewer, but faster, more powerful ships), and aggressive tactics (daring and speedy attacks overwhelming the enemy, a recipe for success in her previous conflicts). The Naval Treaties also provided an unintentional boost to Japan because the numerical restrictions on battleships prompted them to build more aircraft carriers to try to compensate for the United States' larger battleship fleet[citation needed].

The Imperial Japanese Navy was administered by the Ministry of the Navy of Japan and controlled by the Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff at Imperial General Headquarters. In order to combat the numerically superior American navy, the IJN devoted large amounts of resources to creating a force superior in quality to any navy at the time. Consequently, at the beginning of World War II, Japan probably had the most sophisticated Navy in the world.[9] Betting on the speedy success of aggressive tactics, Japan did not invest significantly on defensive organization such as protecting her long shipping lines against enemy submarines, which she never managed to do, particularly under-investing in anti-submarine escort ships and escort aircraft carriers.

The Japanese Navy enjoyed spectacular success during the first part of the hostilities, but American forces ultimately managed to gain the upper hand through decrypting the Japanese naval codes, exploiting the aforementioned Japanese neglect of fleet defense, technological upgrades to its air and naval forces, superior personnel management such as routinely reassigning accomplished combat pilots to provide experienced training of new recruits, and a vastly stronger industrial output. Japan's reluctance to use their submarine fleet for commerce raiding and failure to secure their communications also added to their defeat. During the last phase of the war the Imperial Japanese Navy resorted to a series of desperate measures, including Kamikaze (suicide) actions, which ultimately not only proved futile in repelling the Allies, but encouraged those enemies to use their newly developed atomic bombs to defeat Japan without the anticipated costly battles against so fanatical a defence.

Maritime Self-Defense Force[]

Following Japan's surrender to the Allied Forces at the conclusion of World War II, and the subsequent allied occupation, Japan's entire imperial military was dissolved with the 1947 constitution. The constitution states "The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes." Japan only had a National Security Force and was totally reliant on the USA for protection. However, by 1954 the Self-Defense Forces Act (Act No. 165 of 1954) reorganized the National Security Force as the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF) and The Coastal Safety Force was reorganized as the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), the de facto Japanese Navy.[15][16] The Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) was established as a new branch of the JSDF. General Keizō Hayashi was appointed as the first Chairman of Joint Staff Council—professional head of the three branches.[17] Its offensive capabilities are still restricted due to the nation's constitution.

The post-war Japanese economic miracle enabled Japan to regain great power and leading Maritime power status.[18][19][20] By 1992, the Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) had an authorized strength of 46,000 and maintained some 44,400 personnel and operated 155 major combatants, including thirteen submarines, sixty-four destroyers and frigates, forty-three mine warfare ships and boats, eleven patrol craft, and six amphibious ships. It also flew some 205 fixed-wing aircraft and 134 helicopters. Most of these aircraft were used in antisubmarine and mine warfare operations. By 2015, the JSDF was ranked by Credit Suisse as the 4th most powerful military in the world.[1]

See also[]

- Strike South Group

- Fleet Faction – Navy political group

- Treaty Faction – Navy political group

- May 15 Incident – coup d'état with Navy support

- Imperial Way Faction

- Japanese nationalism

References[]

- Boxer, C. R. (1993) "The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650", ISBN 1-85754-035-2

- Delorme, Pierre, Les Grandes Batailles de l'Histoire, Port-Arthur 1904, Socomer Editions (French)

- Dull, Paul S. (1978) A Battle History of The Imperial Japanese Navy ISBN 0-85059-295-X

- Evans, David C. & Peattie, Mark R. (1997) Kaigun: strategy, tactics, and technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941 Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland ISBN 0-87021-192-7

- Gardiner, Robert (editor) (2001) Steam, Steel and Shellfire, The Steam Warship 1815–1905, ISBN 0-7858-1413-2

- Howe, Christopher (1996) The origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy, Development and technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War, The University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-35485-7

- Ireland, Bernard (1996) Jane's Battleships of the 20th Century ISBN 0-00-470997-7

- Lyon, D. J. (1976) World War II warships, Excalibur Books ISBN 0-85613-220-9

- Nagazumi, Yōko (永積洋子) Red Seal Ships (朱印船), ISBN 4-642-06659-4 (Japanese)

- Tōgō Shrine and Tōgō Association (東郷神社・東郷会), Togo Heihachiro in images, illustrated Meiji Navy (図説東郷平八郎、目で見る明治の海軍), (Japanese)

- Japanese submarines 潜水艦大作戦, Jinbutsu publishing (新人物従来社) (Japanese)

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b O’Sullivan, Michael; Subramanian, Krithika (2015-10-17). The End of Globalization or a more Multipolar World? (Report). Credit Suisse AG. Archived from the original on 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Campbell, Allen; Nobel, David S (1993). Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha. p. 1186. ISBN 406205938X.

- ^ Joanna Rurarz (2014). Historia Korei (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog. p. 89. ISBN 9788363778866.

- ^ Nagoya UniversityThe Naval Organization in the Korean Expedition of the Toyotomi Régime[permanent dead link]

- ^ History of Ming (列傳第二百八外國一 朝鮮) Vol.208 Korea[1] [2] "萬暦 二十五年(1597)七月(July) "七月,倭奪梁山、三浪,遂入慶州,侵閒山。夜襲恭山島,統制元均風靡,遂失閒山要害。閒山島在朝鮮西海口,右障南原,為全羅外藩。一失守則沿海無備,天津、登萊皆可揚帆而至。而我水兵三千,甫抵旅順。

- ^ [3] Archived 2012-04-15 at the Wayback Machine Japanese History Laboratory, Faculty of Letters, Kobe University

- ^ 「征韓録(Sei-kan-roku)」(Public Record of Shimazu clan that Shimazu Hiromichi(島津 久通) wrote in 1671) 巻六(Vol6) "日本の軍兵悉く討果すべきの時至れりと悦んで、即副総兵陳蚕・郭子竜・遊撃馬文喚・李金・張良将等に相計て、陸兵五千、水兵三千を師ゐ、朝鮮の大将李統制、沈理が勢を合わせ、彼此都合一万三千余兵、全羅道順天の海口鼓金と云所に陣し、戦艦数百艘を艤ひして、何様一戦に大功をなすべきと待懸たり。"

- ^ History of Ming (列傳第二百八外國一 朝鮮) Vol.208 Korea[4] "石曼子(Shimazu)引舟師救行長(Konishi Yukinaga), 陳璘(Chen Lin)邀擊敗之"

- ^ 「征韓録(Sei-kan-roku)」 巻六(Vol6) "外立花・寺沢・宗・高橋氏の軍兵、火花を散して相戦ひける間に五家の面々は、順天の城を逃出、南海の外海を廻りて引退く。".

- ^ Naver Battle of Noryang - Dusan EnCyber

- ^ Kerr, George H. (2000). Okinawa: the History of an Island People. (revised ed.) Boston: Tuttle Publishing.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen R. (1996). The Samurai: a military history. Routledge. p. 260. ISBN 1-873410-38-7.

- ^ Murdoch, James (2004). A History of Japan. Routledge. p. 648. ISBN 0-415-15416-2.

- ^ Technology of edo ISBN 4-410-13886-3, p37

- ^ Takei, Tomohisa (2008). "Japan Maritime Self Defense Force in the New Maritime Era" (PDF). Hatou. 34: 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2018.

- ^ 武居智久 (2008). 海洋新時代における海上自衛隊 [Japan Maritime Self Defense Force in the New Maritime Era] (PDF). 波涛 (in Japanese). 波涛編集委員会. 34: 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2018.

- ^ "Japan Self-Defense Force | Defending Japan". Defendingjapan.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ^ "The Seven Great Powers". American-Interest. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ T. V. Paul; James J. Wirtz; Michel Fortmann (2005). "Great+power" Balance of Power. United States of America: State University of New York Press, 2005. pp. 59, 282. ISBN 0-7914-6401-6. Accordingly, the great powers after the Cold War are Britain, China, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, and the United States p.59

- ^ Baron, Joshua (January 22, 2014). Great Power Peace and American Primacy: The Origins and Future of a New International Order. United States: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-137-29948-7.

- ^ Video footage of the Sino-Japanese war: Video (external link).

- ^ :魏略:「倭人自謂太伯之後。」 /晉書:「自謂太伯之後,又言上古使詣中國,皆自稱大夫。」 列傳第六十七 四夷 /資治通鑑:「今日本又云呉太伯之後,蓋呉亡,其支庶入海為倭。」

- ^ Nagazumi Red Seal Ships, p21

- ^ THE FIRST IRONCLADS In Japanese: [10], [11]. Also in English: [12]: "Iron clad ships, however, were not new to Japan and Hideyoshi; Oda Nobunaga, in fact, had many iron clad ships in his fleet." (referring to the anteriority of Japanese ironclads (1578) to the Korean Turtle ships (1592)). In Western sources, Japanese ironclads are described in CR Boxer "The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650", p122, quoting the account of the Italian Jesuit Organtino visiting Japan in 1578. Nobunaga's ironclad fleet is also described in "A History of Japan, 1334-1615", Georges Samson, p309 ISBN 0-8047-0525-9. Korea's "ironclad Turtle ships" were invented by Admiral Yi Sun-sin (1545–1598), and are first documented in 1592. Incidentally, Korea's iron plates only covered the roof (to prevent intrusion), and not the sides of their ships. The first Western ironclads date to 1859 with the French Gloire ("Steam, Steel and Shellfire").

- ^ Corbett Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 2:333

- ^ Howe, p286

External links[]

- Naval history of Japan