Neferneferuaten

| Neferneferuaten | |

|---|---|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | c 1334–1332 BC (Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt) |

| Predecessor | Smenkhkare |

| Successor | Tutankhamun |

| Consort | if Nefertiti: Akhenaten if Meritaten: Smenkhkare |

| Died | c. 1332 BC |

Ankhkheperure-Merit-Neferkheperure/Waenre/Aten Neferneferuaten was a name used to refer to a female pharaoh who reigned toward the end of the Amarna Period during the Eighteenth Dynasty. She is suggested to have been either Meritaten or, more likely, Nefertiti.

The archaeological evidence relates to a woman who reigned as pharaoh toward the end of the Amarna Period during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Her sex is confirmed by feminine traces occasionally found in the name and by the epithet Akhet-en-hyes ("Effective for her husband"), incorporated into one version of her second cartouche.[1][2][3]

She is to be distinguished from the king who used the name Ankhkheperure Smenkhkare-Djeser Kheperu, but without epithets appearing in either cartouche.

If this person is Nefertiti ruling as sole pharaoh, it has been theorized by Egyptologist and Archaeologist Dr. Zahi Hawass that her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.[4]

General chronology[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

As illustrated in a 2011 Metropolitan Museum of Art[5] symposium on Horemheb, the general chronology of the late Eighteenth Dynasty is:

| King | Approx years |

|---|---|

| Akhenaten | 17 years |

| Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten | 2 years |

| Ankhkheperure Smenkhkare | 2 years |

| Tutankhaten/Tutankhamen | 9 years |

| Ay | 4 years |

| Horemheb | 14 years |

There is no broad consensus as to the succession order of Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten. With little dated evidence to fix their reigns with any certainty, the order depends on how the evidence is interpreted. Many encyclopedic sources and atlases will show Smenkhkare succeeding Akhenaten on the basis of tradition dating back to 1845, and some still conflate Smenkhkare with Neferneferuaten.

The period from the 13th year of Akhenaten's reign to the ascension of Tutankhaten is very murky. The reigns of Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten were very brief and left little monumental or inscriptional evidence to draw a clear picture of political events. Adding to this, Neferneferuaten shares her prenomen, or throne name, with Smenkhkare, and her nomen (or birth name) with Nefertiti/Nefertiti-Neferneferuaten making identification very difficult at times.

The Egyptians themselves tried to hide the evidence of the kings reigning during the Amarna from us.[original research?] Neferneferuaten's successor seems to have denied her a king's burial and, later, in the reign of Horemheb, the entire Amarna period began to be regarded as anathema and the reigns of the Amarna period pharaohs from Akhenaten to Ay were expunged from history as these kings' total regnal years were assigned to Horemheb. The result is that 3,300 years later, scholars would have to piece together events and even resurrect the players bit by bit with the evidence sometimes limited to palimpsest.

With the evidence so murky and equivocal, at one time or another, the name, sex, identity, and even the existence of Neferneferuaten has been a matter of debate among Egyptologists. The lack of unique names continues to cause problems in books and papers written before the early 1980s: an object might be characterized as bearing the name of Smenkhkare, when if in fact, the name was "Ankhkheperure", it could be related to one of two people.

Manetho[]

Manetho was a priest in the time of the Ptolemies in the third century BC. His Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt) divided the rulers into dynasties, which forms the basis of the modern system of dating Ancient Egypt. His work has been lost and is known only in fragmentary form from later writers quoting his work. As a result of the suppression of the Amarna kings, Manetho is the sole ancient record available.

Manetho's Epitome, a summary of his work, describes the late Eighteenth Dynasty succession as "Amenophis for 30 years 10 months",[6] who seems likely to be Amenhotep III. Then "his son Orus for 36 years 5 months", this is often seen as a corruption of the name Horemheb with the entire Amarna period attributed to him, but others see Orus as Akhenaten. Next comes "his daughter Acencheres for 12 years 1 month then her brother Rathotis for 9 years". Acencheres is Ankhkheperure according to Gabolde,[7] with a transcription error assumed which converted 2 years, 1 month into the 12 years, 1 month reported (Africanus and Eusebius cite 32 and 16 years for this person) by the addition of 10 years. Most agree that Rathotis refers to Tutankhamun; therefore, the succession order also supports Acencheres as Ankhkheperure. Rathotis is followed by "his son Acencheres for 12 years 5 months, his son Acencheres II for 12 years 3 months",[6] which are inexplicable and demonstrate the limits to which Manetho may be relied upon.

Key evidence[]

There are several items central to the slow unveiling regarding the existence, gender, and identity of Neferneferuaten. These continue to be key elements to various theories today.

- The name of King Ankheprure Smenkhkare-Djeserkheperu was known as far back as 1845 from the tomb of Meryre II. There, he and Meritaten, bearing the title Great Royal Wife, are shown rewarding the tomb's owner. The names of the king have since been cut out but had been recorded by Lepsius c. 1850.[8] A different scene on a different wall depicts the famous Durbar scene, which is dated to regnal year 12.

- A calcite "globular vase" from the tomb of Tutankhamun bears the full double cartouche of Akhenaten alongside the full double cartouche of Smenkhkare. It is the only object to carry both names side by side.[9]

These can be taken to represent that the two were coregents, as was thought to be the case initially, however, the scene in the tomb of Meryre is not dated and Akhenaten is neither depicted nor mentioned in it. It is not known with certainty when the tomb owner died or if he may have lived on to serve a new king. The jar also seems to indicate a coregency, but may be a case of one king associating himself with a predecessor. The simple association of names is not always indicative of a coregency.[10] As with many things of this period, the evidence is suggestive, but not conclusive.

- Indisputable images for Smenkhkare are rare. Aside from the tomb of Meryre II, the adjacent image showing an Amarna king and queen in a garden is often attributed to him. It is completely without inscription, but since they do not look like Tutankhamun nor his queen, they are often assumed to be Smenkhkare and Meritaten, but Akhenaten and Nefertiti are sometimes put forth as well.

- A single wine docket, 'Year 1, wine of the house of Smenkhkare', indicates he probably had a short reign.[11] Another dated to Year 1 from 'The House of Smenkhkare (deceased)'[12] originally, was interpreted to indicate that he died during the harvest of his first year; more recently it has been proposed to mean his estate was still producing wine in the first year of his successor.

- There are several rings with most of his name intact.[13] One example is Item UC23800 in the Petrie Museum. The ring clearly shows the "djeser" and "kherperu" elements of and a portion of the 'ka' glyph.

- Line drawings of a block depicting the nearly complete names of King Smenkhkare and Meritaten as Great Royal Wife were recorded before the block was lost.

A number of items in Tutankhamun's tomb (KV62) were originally intended for Neferneferuaten. Among them Carter 261p(1), a stunning gold pectoral depicting the goddess Nut. Other items include the stone sarcophagus, mummy wrappings, royal figurines; canopic items (chest, coffinettes, and jar stoppers), various bracelets and even shabti figures. Some items are believed to have been at least originally intended for a woman based on the style even when a name cannot be restored. Research by Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves since 2001 has suggested that even the famous gold mask may have originally been intended for Neferneferuaten since her royal name in a cartouche, Ankhkheperure, was found partly erased, on Tutankhamun's funerary mask.[14][15]

- Where named depictions of Smenkhkare are rare, there are no known depictions for Neferneferuaten.

- Of particular interest is a box (Carter 001k) (right, originally one long piece) inscribed with the following:

King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Living in Truth, Lord of the Two Lands, Neferkheperure-Waenre

Son of Re, Living in Truth, Lord of Crowns, Akhenaten, Great in his duration

King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, Ankhkheperure Mery-Neferkheperre

Son of Re, Lord of Crowns, Neferneferuaten Mery-Waenre

Great Royal Spouse, Meritaten, May she Live Forever

- The most definitive inscription attesting to Neferneferuaten is a long hieratic inscription or graffito in the tomb of Pairi ():

Regnal year 3, third month of Inundation, day 10. The King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands Ankhkheperure Beloved of Aten, the Son of Re Neferneferuaten Beloved of Waenre. Giving worship to Amun, kissing the ground to Wenennefer by the lay priest, scribe of the divine offerings of Amun in the Mansion [temple] of Ankhkheperure in Thebes, Pawah, born to Yotefseneb. He says:

- "My wish is to see you, O lord of persea trees! May your throat take the north wind, that you may give satiety without eating and drunkenness without drinking. My wish is to look at you, that my heart might rejoice, O Amun, protector of the poor man: you are the father of the one who has no mother and the husband of the widow. Pleasant is the utterance of your name: it is like the taste of life . . . [etc.]

- "Come back to us, O lord of continuity. You were here before anything had come into being, and you will be here when they are gone. As you caused me to see the darkness that is yours to give, make light for me so that I can see you . . .

- "O Amun, O great lord who can be found by seeking him, may you drive off fear! Set rejoicing in people's heart(s). Joyful is the one who sees you, O Amun: he is in festival every day!"

- For the Ka of the lay priest and scribe of the temple of Amun in the Mansion of Ankhkheperure, Pawah, born to Yotefseneb: "For your Ka! Spend a nice day amongst your townsmen." His brother, the outline draftsman Batchay of the Mansion of Ankhkheperure.[16]

Nicholas Reeves concludes from this Year 3 inscription by Pawah in Pairi's tomb below:

- What we glimpse in the...graffito is a demoralized Amun priest-hood, but one which, following the recent [religious] persecution [of Akhenaten], is again operating officially and, more, surprisingly, within the mortuary temple of the heretic's co-ruler. The Amarna revolution had clearly entered a new phase—perhaps because earthly power was now vested in the hands not of Akhenaten himself but of this same mysterious co-regent, Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten, who was taking a decidedly softer line" toward the Amun priest-hood.[17]

Therefore, Neferneferuaten might have been the Amarna-era ruler who first reached an accommodation with the Amun priests and reinstated the cult of Amun—rather than Tutankhamun as previously thought—since her own mortuary temple was located in Thebes—the religious capital of the Amun priesthood and Amun priests were now working within it, however, Egypt's political administration was still situated at Amarna rather than Thebes under Neferneferuaten's reign.

Female king[]

For some time the accepted interpretation of the evidence was that Smenkhkare served as coregent with Akhenaten beginning about year 15 using the throne name Ankhkheperure. At some point, perhaps to start his sole reign, he changed his name to Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten. An alternative view held that Nefertiti was King Neferneferuaten, in some versions she is also masquerading as a male using the name Smenkhkare.

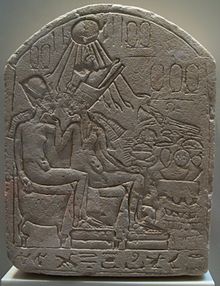

Things remained in this state until the early 1970s when English Egyptologist John Harris noted in a series of papers, the existence of versions of the first cartouche that seemed to include feminine indicators.[18] These were linked with a few items including a statuette found in Tutankhamun’s tomb depicting a king whose appearance was particularly feminine, even for Amarna art which seems to favor androgyny.[19] There are several stele depicting a king along with someone else—often wearing a king's crown—in various familiar, almost intimate scenes. All of them are unfinished or uninscribed and some are defaced. These include:

- An unfinished stele (#17813, Berlin) depicts two royal figures in a familiar, if not intimate, pose. One figure wears the double crown, while the other wears a headpiece which is similar to that from the familiar Nefertiti bust, but is the Khepresh or "blue crown" worn by a king.

- Aidan Dodson cites this stele to support the idea that Nefertiti may have acted at one point as someone with the status of a coregent as indicated by the crown, but not entitled to full pharaonic honors such as the double cartouche.

- Berlin 25574 depicts what clearly seems to be Akhenaten and Nefertiti wearing her flat top headpiece. They are accompanied by four empty cartouches—enough for two kings—one of which seems to have been squeezed in.

A female sovereign, usually identified as Nefertiti, wearing the blue crown of the pharaohs, while affectionately pouring water to Akhenaten, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Altes Museum, Berlin

A female sovereign, usually identified as Nefertiti, wearing the blue crown of the pharaohs, while affectionately pouring water to Akhenaten, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Altes Museum, Berlin- Reeves sees this as an important item in the case for Nefertiti. When the stele was started, she was queen and thus portrayed with the flat top headpiece. She was elevated to coregent shortly afterward and a fourth cartouche was squeezed in to accommodate two kings.[20]

- Flinders Petrie discovered seven limestone fragments of a private stele in 1891, now in the Petrie Museum, U.C.410 sometimes called the Coregency Stela.[21] One side bears the double cartouche of Akhenaten alongside that of Ankhkheperure mery-Waenre Neferneferuaten Akhet-en-hyes ("effective for her husband"), which had been carved over the single cartouche of Nefertiti.[22]

The clues may point to a female coregent, but the unique situation of succeeding kings using identical throne names may have resulted in a great deal of confusion.

A paper by Rolf Krauss of the Egyptian Museum, Berlin speculated a middle way by suggesting that while Smenkhkare/Neferneferuaten was a man, his wife Meritaten might have ruled with the feminine prenomen ‘Ankh-et-kheperure’ after Akhenaten’s death and before Smenkhkare's accession.[1] Smenkhkare then takes the masculine form of her prenomen upon gaining the throne through marriage to her.[23] While this was a step forward in establishing a feminine king, it also sparked a new debate regarding which evidence related to Meritaten and which to Smenkhkare.

Cutting the knot[]

(93) Ankhkheperure desired (f) of Neferkheperure (Akhenaten)

(94) Ankh-et-kheprure (f) desired (f) of Wa-en-Re (using indicators in the name and epithet)

(95) Ankhkheeprure desired of Wa-en-Re

From Tell el Amarna, Flinders Petrie; 1894

In 1988, James P. Allen proposed that it was possible to separate Smenkhkare from Neferneferuaten.[22] He pointed out the name 'Ankhkheperure' was rendered differently depending on whether it was associated with Smenkhkare or Neferneferuaten. When coupled with Neferneferuaten, the prenomen included an epithet referring to Akhenaten such as 'desired of Wa en Re'. There were no occasions where the ‘long’ versions of the prenomen occurred alongside the nomen 'Smenkhkare', nor was the ‘short’ version ever found associated with the nomen 'Neferneferuaten'.

As the adjacent image shows, the differences in the feminine and standard forms are minimal: an extra feminine 't' glyph either in the name or epithet (or both as in #94) that can be lost over time or simply misread especially on smaller items. Following Allen, without regard to the feminine indicators, all three of these names would refer to King Neferneferuaten since they include epithets and associate her with Akhenaten ('desired of Wa-en re / Neferkheperure').

In a 1994 paper, Allen suggested that the different rendering of the names may well indicate two individuals not a single person: "..the evidence itself does not demand an identification of Smenkh-ka-re with Nefer-neferu-aton, and in fact the insistence that the two sets of names must belong to a single individual only weakens each case."[2]

Allen noted another nuance in the names: the reed (jtn) glyph in 'Neferneferuaten' always is reversed to face the seated-woman determinative at the end of the name when associated with the Nefertiti form. Except for a unique case, the reed is not reversed when used with Ankhkheperure. This can be taken to indicate Neferneferuaten is also an individual apart from Nefertiti based on the general difference, or to indicate they are the same person on the basis of the unique rendering in the presence of the seated-person determinative (see below).

Later, the French Egyptologist Marc Gabolde noted that several items from the tomb of Tutankhamun, which had been originally inscribed for Neferneferuaten and read as "...desired of Ahkenaten" were originally inscribed as Akhet-en-hyes or "effective for her husband".[24] His reading was later confirmed by James Allen.

The use of epithets (or lack of them) to identify the king referenced in an inscription eventually became widely accepted among scholars and regularly cited in their work [25] although a case for exempting a particular inscription or instance will occasionally be argued to support a larger hypothesis. As the Smenkhkare versus Neferneferuaten debate subsided, the door was opening for new interpretations for the evidence.

Possible sole reign[]

Allen later showed that Neferneferuaten's epithets were of three types or sets. They were usually in the form of "desired of ...", but were occasionally replaced by "effective for her husband". In a few cases, the names can be followed by 'justified' using feminine attributes.[2] The term 'justified' (maet kheru) is a common indicator that the person referenced is dead. A similar reference associated with Hatshepsut in the tomb of Penyati is taken to indicate she had recently died.[26] Finally, a few of her cartouches bear unique epithets not associated with Akhenaten at all. These include "desired of the Aten" and "The Ruler".[2]

Dr. Allen concluded that the strong affiliation with Akhenaten in the epithets and the number of them made it likely that Neferneferuaten had been his coregent and therefore, preceded Smenkhkare.[2] The "effective..." epithets, then represent a period during which Akhenaten was incapacitated, but may also date from a time after Akhenaten’s death.[27] Finally, the less common 'Akhenaten-less' versions represented a period of sole reign for Neferneferuaten.

James Allen also offered a possible explanation for the use of the same throne name by two successive kings.[2] He suggested that the almost constant references to Akhenaten, in particular the 'desired of Akhenaten' versions, may be proclamations of legitimacy on the part of Neferneferuaten. That is, the epithets are being used to announce or proclaim her as Akhenaten's chosen successor or coregent. One implication then, is there may have been resistance to the choice of Neferneferuaten, or such resistance was anticipated. This appears to be supported by her funerary items being usurped to deny her a king's burial.

Allen suggested that adopting the name Ankhkheperure was "to emphasize the legitimacy of Smenkh-ka-re's claim against that of Akhenaton's "chosen" (/mr/) coregent".[2] That is, a division in the royal house put Smenkhkare on the throne as a rival king to Neferneferuaten. This was offered as a simple and logical reading of the evidence to explain the nature of the epithets, the use of identical prenomens by successive kings and that she was denied a royal burial. With no dated evidence of rival or contemporaneous kings though, it remains conjecture.

The prenomen (left column) and nomen (right column) forms for Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten[2][28][29][30]

Note that aside from rings, the feminine form Ankh-et-kheperure, as yet, is never found in a royal cartouche. At one point, one or more mery Akhet-en-hyes (effective for her husband) had been read as "desired of Akhenaten" probably on the basis of the bird glyph.The fourth set are from the hieratic inscription from the tomb of Pairi (TT139) which seems to have a feminine marker in the nomen's epithet. In the last nomen, the leading reed is reversed as it always is in the cartouche of Nefertiti-Neferneferuaten.

Identity of Neferneferuaten[]

By the late twentieth century, there was "'a fair degree of consensus'"[31] that Neferneferuaten was a female king and Smenkhkare a separate male king, particularly among specialists of the period,[32] although the public and the internet references still often commingle the two. Many Egyptologists believe she also served as coregent on the basis of the stela and epithets, with advocates for Meritaten being notable exceptions. A sole reign seems very likely, given that the Pairi inscription is dated using her regnal years. Opinion is more divided on the placement and nature of the reign of Smenkhkare.

The focus now shifts to the identity of Neferneferuaten, with each candidate having its own advocate(s), a debate which may never be settled to the satisfaction of all.

Nefertiti[]

Nefertiti was an early candidate for King Neferneferuaten, first proposed in 1973 by J. R. Harris.[33] One theory from the 1970s held that Nefertiti was masquerading as the male King Smenkhkare,[34] a view still held by a few—as late as 2001 by Reeves [20] and until 2004 by Dodson.[35]

The apparent use of her name made her an obvious candidate even before Neferneferuaten's gender was firmly established. Remains of painted plaster bearing the kingly names of Neferneferuaten found in the Northern Palace, long believed to be the residence of Nefertiti, supports the association of Nefertiti as the king.[36]

Nefertiti was well in the forefront during her husband's reign and even depicted engaging in kingly activities such as smiting the enemies of Egypt (see image, right).[37] The core premise is that her prominence and attendant power in the Amarna period was almost unprecedented for a queen which makes her the most likely and most able female to succeed Akhenaten.[20][38][39]

The Coregency Stela (UC 410), mentioned earlier, might resolve the question if it were not so badly damaged. The name Neferneferuaten replaced Nefertiti's name on it. How the image of Nefertiti was changed to match the new inscription could settle matters if her image was not missing. If her entire image was replaced it would mean Nefertiti was replaced by someone else called King Neferneferuaten and perhaps that she died. If just a new crown was added to her image, it would argue quite strongly that Nefertiti adopted a new name and title.[40] As it is, the scene seems to be another of the royal family including at least Meritaten. Replacing the name Nefertiti with the name King Neferneferuaten in a depiction of the royal family, still seems to favor Nefertiti as the new king.

The primary argument against Nefertiti has been that she likely died sometime after year 12, the last dated depiction of her. Typically, when someone disappears from inscriptions and depictions, the simplest explanation is that they died. Evidence suggesting this includes:

- Pieces of a shabti—a funerary figure—may indicate her title at death was Great Royal Wife. The shabti is in two pieces with a piece fitting between them assumed. One piece bears her name, Nefertiti-Neferneferuaten, the other the title Great Royal Wife.

- Wine dockets from her estate decline and cease after year 13.[43] Dockets from later years mention only a Queen.

- The floor of the royal tomb intended for her, although apparently not used, shows signs of cuts being started for the final placement of her coffin.[38]

- Meritaten's title as chief queen alongside Akhenaten's name in Tutankhamun's tomb indicates she replaced Nefertiti as in that role. This also seems to be indicated by her designation as "mistress" of the royal house in Amarna Letter EA 11.

This theory has been shown to be incorrect, however, since Nefertiti is now known to have still been alive in Year 16 of Akhenaten—the second-to-last year of her husband's reign.

Nefertiti in regnal year 16[]

In December 2012, the Leuven Archaeological Mission announced the discovery of a hieratic inscription in a limestone quarry that mentions a building project in Amarna. The text is said to be badly damaged, but a doctoral student read the text to indicate a date from regnal year sixteen of Akhenaten and noted that it mentions Nefertiti as Akhenaten's chief wife.[44] The full inscription was not officially published or studied at that time—but parts of it have been published and they clearly demonstrate that Nefertiti, Akhenaten's chief queen, was still alive late in Year 16 of Akhenaten's reign. The inscription is dated explicitly to Year 16 III Akhet day 15 of Akhenaten's own reign and mentions, in the same breath, the presence of Queen Nefertiti—or the "Great Royal Wife, His Beloved, Lady of the Two Lands, Neferneferuaten Nefertiti"—in its third line.[45] The barely-legible five-line text, found in a limestone quarry at Deir el-Bersha, was deciphered and interpreted [46] (the inscription was found in a limestone quarry at Dayr Abū Ḥinnis, just north of Dayr al-Barshā, which is north of Amarna.)[47]

The inscription has now been fully published in a 2014 journal article and Nefertiti's existence late in Akhenaten's reign has been verified.[48] Her name, gender, and location in time could all argue quite strongly for Nefertiti to be the female ruler known as Neferneferuaten.[49] This would also affect various details of the Amarna succession theories proposed. For instance, some Egyptologists, such as Dodson, propose that Neferneferuaten was a coregent for some three years followed by another three years as sole ruler.[50] The inscription would argue against a coregency of more than about a year—if any exists at all—since the inscription attests to Nefertiti's position as Akhenaten's queen just before the start of Akhenaten's final year. Van der Perre writes concerning the discovery of Nefertiti in Akhenaten's Year 16 (this king's second-to-last year):

- ....the existing evidence suggests that at some point Nefertiti assumed the royal office under the name of Ankh(et)kheperure Neferneferuaten. There are slender indications that she could have been Akhenaten's co-regent. This could not have happened before Akhenaten’s 16th regnal year, however, since the quarry inscription at Dayr Abū Ḥinnis still gives the known names and titles of the queen as a Great Royal Wife [of Akhenaten]. The most likely sequel to these events is that Nefertiti eventually adopted the prenomen of her predecessor, Ankhkheperure [Smenkhkare], and combined it with her own name Neferneferuaten. References to her husband were added in her epithets, to confirm the legitimacy of her reign. As time passed, her epithets evolved. After Akhenaten's death, these references to his name were still used, suggesting a deified position of the king. Later in her reign, however, the queen changed the epithets to “Beloved of Aten” and to “the ruler,”....After reigning for three years, Nefertiti disappeared; she probably died....[and Tutankhamun, who was now eight, succeeded her].[51]

This would indicate that Neferneferuaten had an independent reign as an eighteenth dynasty pharaoh after the death of Akhenaten in his seventeenth year.

Sunset theory[]

Even among Egyptologists who advocate Nefertiti as Neferneferuaten, the exact nature of her reign can vary. Reeves sees Nefertiti ruling independently for some time before Tutankhamun and has identified her as Dahamunzu of the Hittite letter-writing episode. In support, Reeves makes clear that Nefertiti did not disappear and is seen in the last years of Akhenaten in the form of the various stelae. The shabti is explained as a votive placed in the tomb of someone close to Nefertiti, such as Meketaten, at a time before she was elevated.[20]

Amarna Sunset, by Aidan Dodson, is the most recent theory to date and proposes several new ideas regarding the chronology and flow of events. Based on the grounds of its location and state of completion, Dodson thinks that the depiction of Smenkhkare in the tomb of Meryre cannot date to later than Year 13/14 or Year 14/15 of Akhenaten at the latest.[52] If accepted, Smenkhkare cannot have had an independent reign and thus, Neferneferuaten must have come after him,[53] the result being that Smenkhkare's reign is entirely that of a coregent, ending about a year later, in Year 14 or 15 of Akhenaten's reign.

Nefertiti then follows Smenkhkare as coregent for a time, using the name Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten. Dodson concludes that Nefertiti was the mother of Tutankhaten, so after Akhenaten dies she continues as regent/coregent to Tutankhaten. Dodson proposes that, in that role, Neferneferuaten helped guide the reformation in the early years of Tutankhaten and conjectures that her turn around is the result of her 'rapid adjustment to political reality'. To support the Nefertiti-Tutankhamun coregency, he cites jar handles found bearing her cartouche and others bearing those of Tutankhaten found in Northern Sinai.[54]

The regnal years attested for Neferneferuaten—two plus a fraction—are not enough to allow for a short coregency with Akhenaten plus an independent reign or another coregency with Tutankhaten. Dodson accounts for this by suggesting that Nefertiti counted her years only after Akhenaten's death which is a generally held view put forth by Murnane to account for the lack of double dates in the New Kingdom,[55] even when a coregency is known to exist. Dodson then speculates that she may later have shared Tutankhamun's regnal dating, in effect deferring senior status at least nominally to him.[56]

Several interesting ideas worthy of consideration are offered, but the central assumption that Nefertiti was mother to Tutankhaten, has since been proven false. DNA evidence published a year after the book concluded that Tutankhaten's parents were sibling children of Amenhotep III, which Nefertiti was not.[57]

Marc Gabolde contends that Tutankhaten never reigned for more than a few months at Amarna. He notes that while Akhenaten, Neferneferuaten, and even Smenkhkare are attested as kings in Amarna, evidence for Tutankhaten is limited to some bezel rings. That is, evidence typically associated with a royal residence is lacking: there are no stamped bricks, reliefs, or paintings; he is not mentioned or depicted in any private tombs, cult stela, royal depictions, or documents; the result is that there is no evidence of King Tutankhaten in Amarna at all. Ring bezels and scarabs bearing his name found, only show the city was still inhabited during his reign.[58] With Neferneferuaten scarcely attested outside Amarna and Tutankaten scarcely attested at Amarna, a coregency or regency seems unlikely.

Regarding the jar sealings, excavators working the Tell el-Borg site note that the two amphorae bearing the cartouche of Neferneferuaten were found in a garbage pit 200 meters away from the location where the two cartouches of Nebkheperure (Tutankhaten) were found. Additionally, sealings and small objects such as bezel rings from many Eighteenth Dynasty characters including Akhenaten, Ay, Queen Tiye, and Horemheb are all present at the site.[59] Egyptologists excavating the site conclude: "Consequently, linking Tutankhamun and Neferneferuaten politically, based on the discovery of their names on amphorae at Tell el-Borg, is unwarranted."[60]

Meritaten[]

Meritaten as a candidate for Neferneferuaten seems to be the most fluid, taking many forms depending on the views of the Egyptologist. She had been put forth by Rolf Krauss in 1973 to explain the feminine traces in the prenomen and epithets of Ankhkheprure and to conform to Manetho's description of a Akenkheres as a daughter of Oros.[1] Although few Egyptologists endorsed the whole hypothesis, many did accept her at times as the probable or possible candidate for a female Ankhkheprure ruling for a time after Smenkhkare's death and perhaps, as regent to Tutankhaten.[61]

The primary argument against Meritaten either as Krauss's pro tempore Ankh-et-kheprure before marriage to Smenkhkare or as Akhenaten's coregent King Neferneferuaten is that she is well attested as wife and queen to Smenkhkare. For her to have later ruled as king means necessarily, and perhaps incredibly for her subjects, that she stepped down from King to the role of King's Wife.[62] This view places Smenkhkare after Neferneferuaten, which requires the Meryre depiction to be drawn 5–6 years after the 'Durbar' depiction it is alongside, and several years after work on tombs had stopped.

The counter to this view comes from Marc Gabolde, who offers political necessity as the reason for Meritaten's demotion.[63] He sees the box (Carter 001k tomb naming her alongside Akhenaten and Neferneferuaten) as depicting Meritaten in simultaneous roles using the name Neferneferuaten as coregent and using her birth name in the role of royal wife to Akhenaten.[64] He has also proposed that the Meryre drawing was executed in advance of an anticipated coronation, which ended up not taking place due to his death.[58]

Most Egyptologists see two names, indicating two individual people, as the simplest and more likely view.[9][65] Most name changes in the Amarna period involved people incorporating -Aten into their name or removing an increasingly offensive -Amun element. Merit-Aten would have had no such need, nor would she need to adopt pharaonic airs such as a double cartouche simply to act on behalf of her husband.

Since Nefertiti has now been confirmed to be living as late as Year 16 of Akhenaten's reign in a 2014 journal paper, however, the Meritaten theory becomes less likely because she would no longer be the most likely living person to be using either the name Neferneferuaten nor "Effective for her husband" as the epithet of a ruling female pharaoh. Secondly, both Aidan Dodson and the late Bill Murnane have stressed that the female ruler Neferneferuaten and Meritaten/Meryetaten cannot be the same person. As Dodson writes:

- ...the next issue is clearly her [i.e., Neferneferuaten's] origins. Cases have been made for her being the former Nefertiti (Harris, Samson and others), Meryetaten (Krauss 1978; Gabolde 1998) and most recently Neferneferuaten-tasherit, [the] fourth daughter of Akheneten (Allen 2006). Of these, Meryetaten’s candidature seems fatally undermined by the existence of the KV62 box fragment JE61500, which gives the names and titles of Akhenaten, Neferneferuaten and Meryetaten as clearly separate individuals.[66][67]

Meritaten as Dakhamunzu theory[]

- See also Dakhamunzu

Marc Gabolde is perhaps the most outspoken and steadfast advocate of Meritaten as King Neferneferuaten. Most recently, he has proposed that Meritaten was raised to coregent of Akhenaten in his final years. She succeeds him as interregnum regent using the name Ankhkheprure, and is the queen of the Dakhamunzu affair with the Hittites.[Note 1] Her ploy succeeds and the Hittite prince Zannanza travels to Egypt and marries her to claim the throne. He adopts the name Smenkhkare,[Note 2] and her throne name. After his death, she adopts full pharoanic prerogatives to continue to rule as King Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten. Since Tutankamun was alive and of royal lineage, Meritaten's actions almost certainly must be taken as intending to prevent his ascension.[68]

The traditional view has long been that the plot took place after the death of Tutankhamun and that Ankhesenamun is the queen, largely based on the fact that she did eventually marry a "servant," Ay. Miller points out that "‘servant’ is likely used in a disparaging manner, rather than literally, and probably with reference to real persons who indeed were being put forth as candidates." If the reference to a 'servant' no longer exclusively indicates Ay, then Meritaten and Nefertiti become candidates as well, since neither has sons known to us.[69]

The Smenkhkare/Zannanza version garners little support among Egyptologists. With the presence of Tutankhamun, Miller points out Meritaten "would presumably have needed the backing of some powerful supporter(s) to carry out such a scheme as the tahamunzu episode, one is left with the question of why this supporter would have chosen to throw his weight behind such a daring scheme".[70] For the plot to succeed, it assumes the young Meritaten with her co-conspirators successfully deceived Suppiluliuma and his envoys (for there was a royal male - Tutankhamun - though not actually her son) and that the plot remained secret during the period of letter writing and Zannanza's travel to Egypt. It assumes the other elements of Egyptian society remained idle with a female interregnum on the throne and a royal male standing by while this played out. On the Hittite side, it assumes that Suppiluliuma was not only willing to risk the consequences if the plot were uncovered, but rather than merely shrewd, Suppiluliuma was ruthless in the extreme and willing to risk the life of his son on a precarious endeavor where he suspected trickery.[71]

Details for the Dakhamunzu/Zannanza affair are entirely from Hittite sources written many years after the events. As Miller states, they were "written in full knowledge of the scheme’s dismal failure, and one cannot dismiss the possibility that Mursili is revising history to some extent, placing full responsibility for the fiasco on the Egyptians, absolving his father of any blame for his failed gamble, giving the impression that he had done everything in his power to ensure that the way was free for Zannanza to take the Egyptian throne."[72]

Neferneferuaten-tasherit[]

In 2006, James Allen proposed a new reading of events.[62] Citing the evidence above, he finds it likely Nefertiti died after year 13. About that time, Akhenaten began attempting to father his own grandchildren. Meritaten and Ankhesenpaaten appear with their daughters in reliefs from Amarna which originally depicted Kiya with her daughter.[73] Meritaten-tasherit and Ankhesenpaaten-tasherit bear the titles 'King’s daughter of his body, his desired...' and 'born of King’s daughter of his body, his desired...'. It is a matter of some debate whether this means Akhenaten actually fathered his own grandchildren, but Allen accepts the titles at face value as a simpler explanation than 'phantom' children being invented to fill space.[74]

When Meritaten gave birth to a girl, Akhenaten may have then tried with Meketaten, whose death in childbirth is depicted in the royal tombs. Though the titles are missing for the infant, it seems certain it also was a girl.[75] Still without a male heir, Akhenaten next tried with Ankhesenpaaten who also bears him a girl (also with titles attesting to Akhenaten as father). His next youngest daughter, Neferneferuaten-tasherit was almost certainly too young, so:

Insofar as can be determined, the primary element in the nomen of a pharaoh always corresponds to the name he (or she) bore before coming to the throne; from the Eighteenth Dynasty onward, epithets were usually added to this name in the pharaoh’s cartouche, but Akhenaten provides the only example of a complete and consistent change of the nomen’s primary element, and even he used his birth name, Amenhotep, at his accession. The evidence of this tradition argues that the coregent bore the name Neferneferuaten before her coronation, and since it now seems clear that the coregent was not Nefertiti, she must have been the only other woman known by that name: Akhenaten’s fourth daughter, Neferneferuaten Jr.[76]

Allen explains the 'tasherit' portion of her name may have been dropped, either because it would be unseemly to have a King using 'the lesser' in their name, or it may have already been dropped when Nefertiti died.[76]

Neferneferuaten-tasherit's age is the first objection often raised. She is thought to have been about ten at the time of Akhenaten's death,[77] but Allen suggests that some daughters may have been older than generally calculated based on their first depicted appearance. Meketaten is believed to have been born about year 4 when is she first depicted. If that is the case, she would only have been ten or eleven when she died in childbirth around year 14,[77] which is a couple of years shy of the age when girls typically become able to conceive at age 13 (Akhenaten and his daughters may have suffered from a hereditary genetic condition called aromatase excess syndrome, which resulted in gynecomastia in males and premature sexual development in females,[78] making childbirth at 11 less improbable).

Allen suggests that perhaps Meketaten's first appearance—and perhaps that of the other daughters—was on the occasion of being weaned at age three in which case her age at death would be the more likely 13 or 14, an argument Dodson also adopts in Amarna Sunset. Likewise, since Ankhesenpaaten bore a child late in Akhenaten's reign, if Neferneferuaten-tasherit was born a year or so after her sister, then Neferneferuaten-tasherit may have been as old as 13 by the end of Akhenaten's reign.[79] The later use of the "effective..." epithets may indicate that she too, was eventually old enough to act as wife to her father, supporting the older age.

Central to the theory is that Akhenaten was being driven to produce a male heir that results in attempts to father his own grandchildren.[79] If the grandchildren are not his or are indeed fictitious, with no progression through his daughters to arrive at Neferneferuaten-tasherit, his choice of her as coregent at least remains a mystery, if not less likely. Without grandchildren, there is less to support the older age estimates. Her age alone need not disqualify her, since it is the same age at which Tutankhaten ascended the throne, but a ten-year-old girl seems unlikely to many.

The strong point of the theory rests with her name: it does not rely on someone changing their name in some awkward fashion to assume the role of Neferneferuaten. She is a less attractive candidate now that the Year 16 graffito for Queen Nefertiti has been verified.

Smenkhkare and the Amarna succession[]

The evidence clearly indicates that Smenkhkare existed and that he was invested with some degree of pharoanic power at some point and died shortly afterwards. Beyond that little else can be said with any certainty at all. As a result, proponents of one theory can assign him a place in time and role with little to argue against it while others can take a wholly different perspective.

For instance, Dodson cites the Meryre depiction to relegate him to a short-lived coregent circa Year 15, with little firm evidence to argue against it. Gabolde cites the Smenkhkare wine docket to support the idea that Smenkhkare must have succeeded Akhenaten. Finally, Allen has used the wine docket and strong association of Neferneferuaten with Akhenaten in her epithets and on stelae to speculate that both may have succeeded Akhenaten, with one as a rival king. An Allen-Dodson hybrid could see Tutankhamun succeeding Akhenaten directly as rival to Neferneferuaten. There are almost as many theories and putative chronologies as there are Egyptologists interested in the period.

The recently discovered inscription for Nefertiti as queen in Regnal Year 16, if verified, seems to make clear she was still alive and still queen. What Egyptologists will make of it remains to be seen, but with proof of her alive in Year 16, it could be seen as supporting her candidacy as Neferneferuaten. On the other hand, advocates for Smenkhkare may make the case that since she is attested as queen just before the start of Akhenaten's final regnal year, then Smenkhkare is more likely to be Akhenaten's successor.

The exact succession cannot be resolved without evidence to more clearly fix Smenkhkare's place in time and role (coregent only or king). If, as the evidence suggests, he was very short-lived, such clarification is not likely to be forthcoming. The result is that the Amarna Succession is dictated by the underlying theory on the identity of King Ankhkheperure-mery Neferkheperure Neferneferuaten-mery Wa en Re.

Reuse of Neferneferuaten's funerary equipment for Tutankhamun's burial[]

According to Nicholas Reeves, almost 80% of Tutankhamun's burial equipment was derived from Neferneferuaten's original funerary goods, including his famous gold mask, middle coffin, canopic coffinettes, several of the gilded shrine panels, the shabti-figures, the boxes and chests, the royal jewelry, etc.[81][82] In 2015, Reeves published evidence showing that an earlier cartouche on Tutankhamun's famous gold mask read, "Ankheperure mery-Neferkheperure" or (Ankheperure beloved of Akhenaten); therefore, the mask originally was made for Nefertiti, Akhenaten's chief queen, who used the royal name Ankheperure when she assumed the throne after her husband's death.[83]

This development implies that either Neferneferuaten was deposed in a struggle for power, possibly deprived of a royal burial—and buried as a queen—or that she was buried with a different set of king's funerary equipment—possibly Akhenaten's own funerary equipment—by Tutankhamun's officials since Tutankhamun succeeded her as king.[84]

Summary[]

There is also little that can be said with certainty about the life and reign of Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten. Most Egyptologists accept that she was a woman and an individual apart from Smenkhkare. Many specialists in the period believe the epigraphic evidence strongly indicates she acted for a time as Akhenaten's coregent.[20][39][62] Whether she reigned before or after Smenkhkare depends on the underlying theory as to her identity.

Based on the Pairi inscription dated to her Third Regnal Year, it appears she enjoyed a sole reign. How much of her reign was as coregent and how much as sole ruler, is a matter of debate and speculation. The same tomb inscription mentions an Amun temple in Thebes, perhaps a mortuary complex, which would seem to indicate that the Amun proscription had abated and the traditional religion was being restored toward the end of her reign.[30][39][62] Since much of her funeral equipment was used in Tutankhamen's burial, it seems fairly certain she was denied a pharaonic burial by her successor.[30][39][62] The reasons for this remain speculation, as does a regency with Tutankhaten.

With so much evidence expunged first by Neferneferuaten's successor, then the entire Amarna period by Horemheb, and later in earnest by the kings of the Nineteenth Dynasty, the exact details of events may never be known. The highly equivocal nature of the evidence often renders it suggestive of something, while falling short of proving it. The various steles, for instance, strongly suggest a female coregent but offer nothing conclusive as to her identity.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Krauss, Rolf. Das Ende der Amarnazeit (The End of the Amarna Period); 1978, Hildesheim; pp.43–47

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Allen, James P. (1994). Nefertiti and Smenkh-ka-re. Göttinger Miszellen 141. pp. 7–17.

- ^ M. Gabolde, ‘Under a Deep Blue Starry Sky’, in P. Brand (ed.), "Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane.", Leiden: E. J. Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 17-21

- ^ Badger Utopia (11 August 2017), Nefertiti - Mummy Queen of Mystery, retrieved 30 October 2017

- ^ A Syposium of Horemhab: General and King of Egypt See the first 8 minutes of this 2011 Metropolitan Museum of Art presentation. As the video notes, the order and dates are "under discussion".

- ^ Jump up to: a b MANETHO, The Loeb Classical Library; 1940, English translation by W. G. Waddell, p 102-103

- ^ Gabolde, Marc. D’Akhenaton à Tout-ânkhamon, 1998; pp.145-185

Some internet theories equate Achencheres with Akhenaten. - ^ de Garies Davies, N. 1905. The Rock Tombs of El Amarna, Part II: The Tombs of Panehesy and Meryra II. Archaeological Survey of Egypt. F. L. Griffith. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. See Line Drawing from 'The Rock Tombs of El Amarna'. Lepsius rendering of the names is lower right, and were originally in the upper right where Meritaten's cartouche is quite clearly shown.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allen, James P., "The Amarna Succession", in "Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane", p.2

- ^ Murnane, W.; (1977) Ancient Egyptian Coregencies, pp.213–15

- ^ Pendlebury, J. D. S. ; The City of Akhenaten (1951), Part III, p.164

- ^ Pendlebury, J. D. S. ; The City of Akhenaten (1951), Part III, pl lxxxvi and xcvii

- ^ Petrie, W M Flinders (1894). Tell el Amarna. pp. pl. XV. 103–104.

- ^ Reeves 2014, p. 511.

- ^ James Seidel, Tutankhamun’s mask: Evidence of an erased name points to the fate of heretic queen Nefertiti, 26 November 2015, News Corp

- ^ Murnane, W; Texts from the Amarna Period, Atlanta: Scholars Press (1995). Note: Gardiner, JEA 14 (1928), pp. 10–11 and pls. 5–6;, Reeves (False Prophet, 2001. p.163) and Murnane all give the date as 10th Day, Month 3, Akhet. Dodson (2009) reports the date as "unequivocally" 3rd day, Month 4, Akhet. The difference is 23 days.

- ^ Reeves, C. Nicholas; Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet; 2001. p.164

- ^ J. R. Harris, Neferneferuaten, "Göttinger Miszellen" 4 (1973), 15-17;

Neferneferuaten Rediviva, "Acta Orientalia" 35 (1973), 5-13;

Neferneferuaten Regnans, "Acta Orientalia" 36 (1974), 11-21;

Akhenaten or Nefertiti?, "Acta Orientalia" 38 (1977), 5-10. - ^ Burton, Harry (Photographer). "Statuette of the king upon a leopard". Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation: The Howard Carter Archives. Griffith Institute. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Reeves, C. Nicholas; Akhenaten, Egypt's False Prophet; (2001) Thames and Hudson

- ^ Pendlebury J., Samson, J. et al; City of Akhenaten, Part III (1951)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allen, James P. , Two Altered Inscriptions of the Late Amarna Period, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 25 (1988); pp.117-121.

- ^ In fact, portions of Krauss's hypothesis may have been put forward twice previously. See Reeves, Nicholas; Orientalistische Literaturzeitung, vol. 78, no. 6 (1983)

- ^ Gabolde, Marc (1998). "D'Akhenaton à Tout-ânkhamon": 147–62, 213–219. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Allen (1994); Gabolde (1998); Eaton-Krauss and Krauss(2001); Hornung (2006); von Beckerath (1997); Allen (2006); Krauss (2007); Murnane (2001)

They otherwise hold very different views on the succession, chronology, and identity of Neferneferuaten. - ^ Murnane, W; (1977) p.42

- ^ Gabolde, Marc. D’Akhenaton à Tout-ânkhamon, 1998; pp.156-157; This involves Isis' relationship with Osiris.

- ^ Dodson, A; Amarna Sunset (2009), appendix 3

- ^ Allen, James P.; The Amarna Succession (2006); in P. Brand (ed.), "Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane"; Archived from the original

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Giles, 2001

- ^ Miller, J; Amarna Age Chronology and the Identity of Nibhururiya in Altoriental. Forsch. 34 (2007); p 272

- ^ e.g. Murnane, J.; The End of the Amarna Periode Once Again, (2001); Allen, J 1998, 2006; Gabolde, M.; Das Ende der Amarnazeit, (2001); Hornung, E; The New Kingdom in Ancient Egyptian Chronology (2006); Miller, J. Amarna Age Chronology (2007); Dodson A.; Amarna Sunset (2009).

- ^ Harris, J.R. Neferneferuaten Rediviva; 1973 in "Acta Orientalia" 35 pp. 5–13

Harris, J.R. Neferneferuaten Regnans; 1973 in Göttinger Miszellen 4 pp. 15–17 - ^ Samson, J; City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti; Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1972; ISBN 978-0856680007

- ^ Dodson & Hilton (2004); p 285

- ^ Dodson, A; Amarna Sunset (2009) p. 43

- ^ Giles, Frederick. J., Ikhnaton Legend and History; 1970; Associated University Press; 1972 US; p 59

- ^ Jump up to: a b Giles, F; 1972

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Dodson, A; Amarna Sunset, The American University in Cairo Press, 2009

- ^ Dodson, A; (2009); p. 43

- ^ Martin, G. T., The Rock Tombs of El-'Amarna. Part VII. The Royal Tomb at El-'Amarna, 1974. The Objects. (Vol. I.) London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- ^ Bovot, J.-L. (1999). Un chaouabti pour deux reines amarniennes?. Égypte Afrique et Orient 13. pp. 31–34.

- ^ Aldred, Cyril (1988). Akhenaten: King of Egypt. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27621-8.

- ^ Dayr al-Barsha Project Press Release, Dec 2012; http://www.dayralbarsha.com/node/124 Archived 19 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Athena Van der Perre, "Nofretetes (vorerst) letzte dokumentierte Erwähnung," (Nefertiti's (now) latest documented attestation) in: Im Licht von Amarna - 100 Jahre Fund der Nofretete. [Katalog zur Ausstellung Berlin, 7 December 2012 – 13 April 2013]. (7 December 2012 – 13 April 2013) Petersberg, pp.195-197

- ^ Dayr al-Barsha Project featured in new exhibit 'Im Licht von Amarna' at the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung in Berlin Archived 19 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine 12 June 2012

- ^ Christian Bayer, "Ein Gott für Aegypten - Nofretete, Echnaton und der Sonnenkult von Amarna" Epoc, 04-2012. - pp.12-19

- ^ Athena van der Perre, The Year 16 graffito of Akhenaten in Dayr Abū Ḥinnis. A Contribution to the Study of the Later Years of Nefertiti, Journal of Egyptian History (JEH) 7 (2014), pp.72-73 & 76-77

- ^ van der Perre, JEH 7 (2014) pp.82-87 & 96-102

- ^ Dodson, A; (2009) p. 50

- ^ A. van der Perre, JEH 7 (2014), pp.101-102

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Amarna Sunset:the late-Amarna succession revisited in Beyond the Horizon. Studies in Egyptian Art, Archaeology and History and history in Honour of Barry J. Kemp, ed. S, Ikram and A. Dodson, pp.32-33 Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquites, 2009.

- ^ Dodson, Amarna Sunset 2009, pp. 27-29

- ^ Dodson, Amarna Sunset 2009, p. 51, 45-46

- ^ Murnane, W.; Ancient Egypt Coregencies (1977) p 31-32

- ^ Dodson, Amarna Sunset 2009, pp.45-46

- ^ JAMA. 2010 Feb 17; Ancestry and pathology in King Tutankhamun's family; Hawass Z, Gad YZ, Ismail S, Khairat R, Fathalla D, Hasan N, Ahmed A, Elleithy H, Ball M, Gaballah F, Wasef S, Fateen M, Amer H, Gostner P, Selim A, Zink A, Pusch CM. Source Supreme Council of Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=185393

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gabolde, M; Ancient Near East Forum, Dec 2007

- ^ Hoffemeir, Van Dijk. "New Light on the Amarna Period from North Sinai".

- ^ Hoffemeir, Van Dijk; New Light on the Amarna Period" (2010) pp.201-202

- ^ J. Tyldesley, Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt, 2006, Thames & Hudson, pp.136-137;

also Gabolde, M,; Under a Deep Blue Starry Sky, P. Brand (ed.), in "Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane", (2006) pp.17-21 - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Allen, James P.; The Amarna Succession (2006); in P. Brand (ed.), "Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane"; Archived from the original Archived 1 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gabolde, Marc. D’Akhenaton à Tout-ânkhamon, 1998; pp.178–183

- ^ Gabolde, Marc. D’Akhenaton à Tout-ânkhamon, 1998; pp.187-226

- ^ Murnane, W.; The End of the Amarna Period Once Again, 2001

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Amarna Sunset:the late-Amarna succession revisited in Beyond the Horizon. Studies in Egyptian Art, Archaeology and History and history in Honour of Barry J. Kemp, ed. S, Ikram and A. Dodson, p.32 Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquites, 2009.

- ^ William J. Murnane, The End of the Amarna Period Once Again’, Orientalistische Literaturzeitung (OLZ) Vol. 96 (2001), p.21

- ^ Miller, J; Amarna Age Chronology (2007) p.275; to wit Gabolde 1998; 2001; 2002

- ^ Miller, J.; The Amarna Age Chronology (2007) p.261

- ^ Miller, J.; The Amarna Age Chronology (2007) p.275 n104

- ^ Miller, J.; The Amarna Age Chronology (2007) pp.260-261; Miller believes Suppiluliuma was indeed that "brutal [and] unscrupulous"; implicitly he must have been much less aware of the state of affairs at Amarna court than Neferneferuaten was of minutiae regarding Suppiluliuma such as his affiliation with the Hittite sun god. p.273 n94

- ^ Miller, J.; Amarna Age Chronology (2007) p.262

- ^ Roeder, Amarna-Reliefs aus Hermopolis, pls. 19 (234-VI) and 106 (451-VIIA). Also D. Redford, Studies on Akhenaten at Thebes, II, JARCE 12 (1975), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Allen, J, Amarna Succession (2006); p 9-10, p9 n. 34

- ^ van Dijk, Jacobus; The Death of Meketaten in Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane; (2006) pp 7-8

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allen; Amarna Succession; p15

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tyldesley, Joyce. Nefertiti: Egypt's Sun Queen; Penguin; 1998; ISBN 0-670-86998-8

- ^ Irwin M. Braverman; et al. (2009). "Akhenaten and the Strange Physiques of Egypt's 18th Dynasty". Ann Intern Med. 150 (8): 556–60. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00010. PMID 19380856. S2CID 24766974.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allen, James P.; The Amarna Succession in "Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane"

- ^ Was King Tut's Tomb Built for a Woman?, retrieved 24 October 2017

- ^ Nicholas Reeves Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered BES 19 (2014), pp.511-522

- ^ Peter Hessler, Inspection of King Tut's Tomb Reveals Hints of Hidden Chambers National Geographic, 28 September 2015

- ^ Nicholas Reeves, The Gold Mask of Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten, Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, Vol.7 No.4, (December 2015) pp.77-79 & click download this PDF file

- ^ Nicholas Reeves,Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered BES 19 (2014), pp.523-524

Notes[]

- ^

Briefly, an Egyptian queen writes to Suppiluliuma asking for him to send a son for her to marry for she has no sons. In marrying her, the son will become King of Egypt. The Hittite king is wary and sends an envoy to verify the lack of a male heir. The queen writes back, rebuking Suppiluliuma for suggesting she lied about a son and indicates she is loath to marry a "servant" (as she was being pressed to do).

A key element in the Hittite sources is that Zannanza died not long after departing. It has been supposed that he was murdered at the border of Egypt (Brier) to thwart the plot. As there is no evidence as to when or where he died nor that he was murdered, Gabolde believes that he completed the trip and died only after ascending the throne as Smenkhkare.

The traditional view has been that Tutankhamun's widow is the queen in question because she had no sons and eventually was married to a "servant", Ay. Reeves has long held that the queen was Nefertiti, who was The Queen par excellence of the period. - ^ Gabolde and others have long noted that the name Smenkhkare-Djeser Kheperu with the theophoric element of Re and somewhat lofty epithet seems much more like a throne name than a birth name. A name change does seem likely to many even if he is Egyptian. The change may have been simply adopting the 'Holy of Manifestations' epithet or changing the theophoric element to 'Re' to gain acceptance from both Atenists and traditionalists.

Further reading[]

Each of the leading candidates have their own proponents among Egyptologists, whose work can be consulted for more information and many more details for a given candidate. Several of the works of Nicholas Reeves and Aidan Dodson advocate for Nefertiti as Neferneferuaten. Marc Gabolde has written several papers and at least one book (in French) supporting Meritaten. James Allen's previous work in this area primarily dealt with establishing the female gender of Neferneferuaten and then as an individual apart from Smenkhkare. His paper on "The Amarna Succession" is his first theory as to identity of King Neferneferuaten, having previously cited Nefertiti or Meritaten as the probable or possible identity depending on the state of the evidence.

- Aldred, Cyril, Akhenaten, King of Egypt (Thames & Hudson, 1988).

- Aldred, Cyril (1973). Akhenaten and Nefertiti. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Aldred, Cyril (1984). The Egyptians. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Allen, James P. (2006). "The Amarna Succession" (PDF). Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2008.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- Dodson, Aidan. Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation. The American University in Cairo Press. 2009, ISBN 978-977-416-304-3

- Freed, Rita E., Yvonne J. Markowitz, and Sue H. D'Auria (ed.) (1999). Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten - Nefertiti - Tutankhamen. Bulfinch Press. ISBN 0-8212-2620-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gabolde, Marc, Under a Deep Blue Starry Sky in "Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane"; Gabolde - Starry Sky

- Giles, Frederick. J., Ikhnaton Legend and History (1970, Associated University Press, 1972 US)

- Giles, Frederick. J. The Amarna Age: Egypt (Australian Centre for Egyptology, 2001)

- Hornung, Erik, Akhenaten and the Religion of Light, translated by David Lorton, Cornell University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8014-3658-3)

- Miller, Jared; Amarna Age Chronology and the Identity of Nibhururiya in the Light of a Newly Reconstructed Hittite Text (2007); Altoriental. Forsch. 34 (2007) 2, 252–293

- Redford, Donald B., Akhenaten: The Heretic King (Princeton University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-691-03567-9)

- Redford, Donald B.;Akhenaten: The Heretic King (1984) Princeton University Press

- Reeves, C. Nicholas., Akhenaten, Egypt's False Prophet (Thames & Hudson, 2001).

- Reeves, C. Nicholas., The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames & Hudson, 1 November 1990, ISBN 0-500-05058-9 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-500-27810-5 (paperback)

- Reeves, Nicholas (2014). "Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered". In A. Oppenheim; O. Goelet (eds.). The Art and Culture of Ancient Egypt. Studies in Honor of Dorothea Arnold.

- Theis, Christoffer Der Brief der Königin Daḫamunzu an den hethitischen König Šuppiluliuma I. im Lichte von Reisegeschwindigkeiten und Zeitabläufen, in: Thomas R. Kämmerer (Hrsg.): Identities and Societies in the Ancient East-Mediterranean Regions. Comparative Approaches. Henning Graf Reventlow Memorial Volume (= AAMO 1, AOAT 390/1). Münster 2011, S. 301–331

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Nefertiti: Egypt's Sun Queen. Penguin. 1998. ISBN 0-670-86998-8

- The Amarna Project

- 1330s BC deaths

- 14th-century BC births

- 14th-century BC Pharaohs

- 14th-century BC women rulers

- Amarna Period

- Atenism

- Historical negationism in ancient Egypt

- Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt

- Female pharaohs