Neural basis of self

The neural basis of self is the idea of using modern concepts of neuroscience to describe and understand the biological processes that underlie humans' perception of self-understanding. The neural basis of self is closely related to the psychology of self with a deeper foundation in neurobiology.

Experimental techniques[]

In order to understand how the human mind makes the human perception of self, there are different experimental techniques. One of the more common methods of determining brain areas that pertain to different mental processes is by using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. fMRI data is often used to determine activation levels in portions of the brain. fMRI measures blood flow in the brain. Areas with higher blood flow as shown on fMRI scans are said to be activated. This is due to the assumption that portions of the brain receiving increased blood flow are being used more heavily during the moment of scanning.[1] Positron emission tomography is another method used to study brain activity.[2]

Self-awareness[]

Anatomy[]

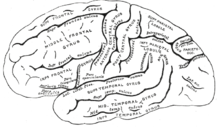

Two areas of the brain that are important in retrieving self-knowledge are the medial prefrontal cortex and the medial posterior parietal cortex.[3] The posterior cingulate cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex are thought to combine to provide humans with the ability to self-reflect. The insular cortex is also thought to be involved in the process of self-reference.[4]

Embodiment[]

The sense of embodiment is critical to a person's conception of self. Embodiment is the understanding of the physical body and its relation to oneself.[5] The study of human embodiment currently has a large impact on the study of human cognition as a whole. The current study of embodiment suggests that sensory input and experiences impact human's overall perception. This idea somewhat challenges previous ideas of human cognition because it challenges the idea of the human mind being innate.[6]

There are two portions of the brain that have recently been found to have a large importance on a person's perception of self. The temporoparietal junction, located in the cortex is one of these brain regions. The temporoparietal junction is thought to integrate sensory information. The second portion of the brain thought to be involved in perception of embodiment is the extrastriate body area. The extrastriate body area is located in the lateral occipitotemporal cortex. When people are shown images of body parts, the extrastriate body area is activated. The temporoparietal junction is involved in sensory integration processes while the extrastriate body area deals mainly with thoughts of and exposure to human body parts. It has been found that the brain responds to stimuli that involve embodiment differently from stimuli that involve . During task performance tests, a person's body position (whether he or she is sitting or laying face up) affects how the extrastriate body area is activated. The temporoparietal junction, however, is not affected by a person's particular body position. The temporoparietal junction deals with disembodied rather than embodied self-location, explaining why a person's physical position does not affect its activation. Self-location as related to a person's sense of embodiment is related to his or her actual location in space.[5]

Autobiographical memories[]

The information people remember as autobiographical memory is essential to their perception of self. These memories form the way people feel about themselves. The left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex are involved in the memory of autobiographical information.[7]

Morality[]

Morality is an extremely important defining factor for humans. It often defines or contributes to people's choices or actions, defining who a person is. Making moral decisions, much like other neural processes has a clear biological basis. The anterior and medial prefrontal cortex and the superior temporal sulcus are activated when people feel guilt, compassion, or embarrassment. Guilt and passion activate the mesolimbic pathway, and indignation and disgust are activated by the amygdala. There is clearly a network involved with the ideas of morality.[8]

Views of self[]

In order to explain how a human views him or herself, two different conceptual views of self-perception exist: the individualist and collectivistic views of self. The individualistic view of self involves people's perception of themselves as a stand-alone individual. This is thought of as a somewhat permanent perception of oneself that is unaffected by environmental and temporary cues and influences. People who view themselves in an individualistic sense describe themselves with personality traits that are permanent descriptions unrelated to particular situations. The collectivistic view of self, however, involves people's perception of themselves as members of a group or in a particular situation. The view people have of themselves in a collectivistic sense is entirely dependent on the situation they are in and the group with which they are interacting. These two ideas of self are also called self-construal styles.[9] There is neurobiological evidence supporting these two definitions of self-construal styles. fMRI data has been used to understand the biology of both the individualistic and collectivistic view of self. Certain people tend to view themselves in almost exclusively a collectivistic sense or an individualistic sense. When people have to describe themselves in a collectivistic way (as a part of a group), those who tend to view themselves collectivistically show greater fMRI activation in the medial prefrontal cortex than those who view themselves individualistically. The reverse is true when people describe themselves individualistically.[9]

Impaired views of self[]

The study of the human mind in diseased states provides valuable insight into how the mind works in healthy individuals. A multitude of diseases are studied to understand altered perceptions of self and what causes these impairments.

Autism[]

Autism is a disorder in which those affected experience impaired social interactions, communication, and behaviors.[10] A new approach to studying autism is to focus on individuals’ perception of self rather than understanding the individual's social interactions. A common thought is that understanding of the differences between the self and others are impaired. However, the exact biological mechanism of self-understanding in autistic children is currently unknown. It has been found that there are significant differences in brain activation in self and other situations in autistic children when compared to children who do not have autism. In adults who do not have autism, during self-recognition tasks, the inferior frontal gyrus and the inferior parietal lobule in the right hemisphere are activated. Children who do not have autism show activation in these areas when performing face processing tasks for their own faces and those of others. Children with autism, however, only show activation in these areas when recognizing their own faces. The activation in the inferior frontal gyrus is less in children with autism than in those who do not have autism.[11]

Schizophrenia[]

The cortical midline structure is extremely important in the understanding of the self, especially during the task of self-reflection. Many researchers believe that self-reference plays a role in the expression of psychoses. The disturbance of the individual's self may be underlying the manifestation of these psychoses. Occurrences such as hallucinations and delusions may originate with disruptions of a person's perception of the self. Understanding the differences in those who have psychoses and those who do not can aid in diagnoses and treatment of those diseases. Those who are prone to psychoses such as schizophrenia, when describing positive traits about themselves show increased activation in the left insula, right dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, and left ventromedial prefrontal cortex. When they use negative traits to describe themselves, those who are prone to psychoses show higher activation in the bilateral insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and right dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.[4]

After strokes[]

Sometimes after strokes patients' perception of self changes. Often after a stroke, patients report their perception of self in more negative terms than before their stroke. [12]

Aging[]

It has been found that humans’ ideas of themselves are established early in life but that the perception can change as others ideas are combined with their own. There are differences in the areas activated during self-knowledge retrieval between adults and children. This suggests a difference in self-knowledge neurobiologically due to normal aging. The prefrontal cortex and the medial posterior parietal cortex have been found to be activated when adults perform self-knowledge retrieval processes. Tests consist of presenting subjects with self-description phrases and allowing the subject to respond yes or no depending on whether or not the phrase describes him or herself. During this task, patients brains are fMRI scanned. These results can then be compared to fMRI data of the same patients when they are asked if the same phrases describe another individual, such as a well-known fictional character. The medial prefrontal cortex is activated more strongly for subjects when they are describing themselves than when they are describing others. However, children show greater medial prefrontal cortex activation than adults when performing self-knowledge retrieval tasks. Additionally, children and adults activate different specific regions in the medial prefrontal cortex. Adults activate the posterior precuneus more while children activate the anterior precuneus and the posterior cingulate.[3] The understanding of the areas of the brain most frequently activated in children and adults can also provide information about how children, adolescents, and adults view themselves differently. Older children more significantly activate the medial prefrontal cortex because they deal with introspection much less frequently than adults and adolescents. Children have decreased specificity in skills than adults, so they show greater activation during spatial tasks. This is explained by the idea that with increased expertise in a task, decreased interest in wide spatial parameters occurs. When a person is an expert, he or she is able to be more focused in his or her performance. The difference in performance between adults and children is thought to be attributable to different perceptions of the self whether it is more introspective or more concerned with the surroundings and environment.[3]

References[]

- ^ About Functional MRI. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-01-09. Retrieved 2012-01-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed November 21, 2011. - ^ Damasio AR, Grabowski TJ, Bechara A, et al. Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self-generated emotions. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(10):1049-1056.

- ^ a b c Pfeifer, J. H., Lieberman, M. D., & Dapretto, M. (2007). "I know you are but what am I?!": Neural bases of self- and social knowledge retrieval in children and adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(8), 1323-1337.

- ^ a b Modinos G, Renken R, Ormel J, Aleman A. Self-reflection and the psychosis-prone brain: an fMRI study. Neuropsychology [serial online]. May 2011;25(3):295-305. Available from: MEDLINE with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Arzy, S., Thut, G., Mohr, C., Michel, C. M., & Blanke, O. (2006). Neural basis of embodiment: Distinct contributions of temporoparietal junction and extrastriate body area. Journal of Neuroscience, 26(31), 8074-8081.

- ^ Pezzulo G, Barsalou LW, Cangelosi A, Fischer MH, McRae K, Spivey MJ. The mechanics of embodiment: a dialog on embodiment and computational modeling. Frontiers In Psychology.2:5-5.

- ^ Botzung, A., Denkova, E., Ciuciu, P., Scheiber, C., & Manning, L. (2008). The neural bases of the constructive nature of autobiographical memories studied with a self-paced fMRI design. Memory, 16(4), 351-363.

- ^ Moll, J., de Oliveira-Souza, R., Garrido, G. J., Bramati, I. E., Caparelli-Daquer, E. M. A., Paiva, M., et al. (2007). The self as a moral agent: Link-ling the neural bases of social agency and moral sensitivity. Social Neuroscience, 2(3-4), 336-352.

- ^ a b Chiao, J. Y., Harada, T., Komeda, H., Li, Z., Mano, Y., Saito, D., et al. (2009). Neural Basis of Individualistic and Collectivistic Views of Self. Human Brain Mapping, 30(9), 2813-2820.

- ^ Carayol J, Schellenberg GD, Dombroski B, Genin E, Rousseau F, Dawson G. Autism risk assessment in siblings of affected children using sex-specific genetic scores. Molecular Autism.2(1):17-17.

- ^ Uddin, L. Q., Davies, M. S., Scott, A. A., Zaidel, E., Bookheimer, S. Y., Iacoboni, M., et al. (2008). Neural Basis of Self and Other Representation in Autism: An fMRI Study of Self-Face Recognition. PLoS ONE, 3(10).

- ^ Ellis-Hill CS, Horn S. Change in identity and self-concept: a new theoretical approach to recovery following a stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2000;14(3):279-287.

- Self

- Conceptions of self

- Neuroscience books