Nicky Hopkins

Nicky Hopkins | |

|---|---|

Hopkins in 1973 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Nicholas Christian Hopkins |

| Born | 24 February 1944 Perivale, Middlesex, England, UK |

| Died | 6 September 1994 (aged 50) Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Genres | Rock and roll, boogie woogie, blues |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | Keyboards |

| Years active | 1960–1994 |

| Labels | Fontana |

| Associated acts | Screaming Lord Sutch and the Savages, Cliff Bennett and the Rebel Rousers, Cyril Davies All Stars, Jerry Garcia Band, The Kinks, The Rolling Stones, The Jeff Beck Group, Sweet Thursday, The Beatles, Steve Miller Band, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Who, Badfinger, Night, Donovan |

Nicholas Christian Hopkins (24 February 1944 – 6 September 1994) was an English pianist and organist. Hopkins recorded and performed on many British and American pop and rock music releases from the 1960s through the 1990s including many songs by The Rolling Stones, The Kinks and The Who.[1]

Early life[]

Nicholas Christian Hopkins was born in Perivale, Middlesex, England, on 24 February 1944. He began playing the piano at the age of three. He attended Sudbury Primary School in Perrin Road[2] and Wembley County Grammar School,[3] which now forms part of Alperton Community School, and was initially tutored by a local piano teacher; in his teens he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music in London.[4] He suffered from Crohn's disease for most of his life.[5]

His poor health and repeated surgery later made it difficult for him to tour, and he worked mainly as a session musician for most of his career.[6] Hopkins' studies were interrupted in 1960 when he left school at 16 to become the pianist with Screaming Lord Sutch's Savages until, two years later, he and fellow Savages Bernie Watson, Rick Brown (aka Ricky Fenson) and Carlo Little joined the renowned blues harmonica player Cyril Davies, who had just left Blues Incorporated, and became the Cyril Davies (R&B) All-Stars.[4] Hopkins played piano on their first single, Davies's much-admired theme tune "Country Line Special".[7] However, he was forced to leave the All Stars in May 1963 for a series of operations that almost cost him his life and he was bed-ridden for 19 months in his late teenage years. During Hopkins's convalescence Davies died of leukemia and the All Stars disbanded.[4] Hopkins's frail health led him to concentrate on working as a session musician instead of joining bands, although he left his mark performing with a wide variety of famous bands.[8] He quickly became one of London's most in-demand session pianists and performed on many hit recordings from this period.

With The Rolling Stones[]

Hopkins played with the Rolling Stones on all their studio albums from Between the Buttons in 1967 through Tattoo You in 1981, excepting for Some Girls (1978). Among his contributions, he supplied the prominent piano parts on "We Love You" and "She's a Rainbow" (both 1967), "Sympathy for the Devil" and "No Expectations" (1968), "Monkey Man" (1969), "Sway" (1971), "Loving Cup" and "Ventilator Blues" (1972), "Angie" (1973), "Time Waits for No One" (1974) and "Waiting on a Friend" (recorded 1972, released in 1981). When working with the band during their critical and commercial zenith in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Hopkins tended to be employed on a wide range of slower ballads, uptempo rockers and acoustic material; conversely, longtime de facto Stones keyboardist Ian Stewart only played on traditional major key blues rock numbers of his choice, while Billy Preston often featured on soul- and funk-influenced tunes. Hopkins's work with the Rolling Stones is perhaps most prominent on their 1972 studio album, Exile on Main St., where he contributed in a variety of musical styles.

Along with Ry Cooder, Mick Jagger, Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts, Hopkins released the 1972 album Jamming with Edward! It was recorded in 1969, during the Stones' Let It Bleed sessions, when guitarist Keith Richards was not present in the studio. The eponymous "Edward" was an alias of Nicky Hopkins derived from studio banter with Brian Jones. It was incorporated into the title of an outstanding Hopkins instrumental performance ("Edward, the Mad Shirt Grinder") released on Shady Grove in December 1969. Hopkins also contributed to the Jamming With Edward! cover art.

Hopkins was added to the Rolling Stones touring line-up for the 1971 Good-Bye Britain Tour, as well as the 1972 North American tour and the 1973 Pacific tour. He contemplated forming his own band with multi-instrumentalist Pete Sears and drummer Prairie Prince around this time but decided against it after the Stones tour. Hopkins failed to make the Rolling Stones' 1973 European tour due to ill health and, aside from a guest appearance in 1978, did not play again with the Stones live on stage.

With The Kinks[]

Hopkins was invited in 1965 by producer Shel Talmy to record with The Kinks. He recorded 4 studio albums: The Kink Kontroversy (1965), Face to Face (1966), Something Else by The Kinks (1967) and The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (1968).

The relationship between Hopkins and the Kinks deteriorated after the release of The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, however. Hopkins maintained that "about seventy percent" of the keyboard work on the album was his, and was incensed when Ray Davies apparently credited himself for the majority of the keyboard playing.[9]

Despite Hopkins's grudge against him, Davies spoke positively of his contributions in a New York Times interview in 1995, a few months after Hopkins death:

Nicky, unlike lesser musicians, didn't try to show off; he would only play when necessary. But he had the ability to turn an ordinary track into a gem – slotting in the right chord at the right time or dropping a set of triplets around the back beat, just enough to make you want to dance. On a ballad, he could sense which notes to wrap around the song without being obtrusive. He managed to give "Days," for instance, a mysterious religious quality without being sentimental or pious.

Nicky and I were hardly bosom buddies. We socialized only on coffee breaks and in between takes. In many ways, I was still in awe of the man who in 1963 had played with the Cyril Davies All Stars on the classic British R & B record, "Country Line Special." I was surprised to learn that Nicky came from Wembley, just outside of London. With his style, he should have been from New Orleans, or Memphis.

… His best work in his short spell with the Kinks was on the album Face to Face. I had written a song called "Session Man," inspired partly by Nicky. Shel Talmy asked Nicky to throw in "something classy" at the beginning of the track. Nicky responded by playing a classical- style harpsichord part. When we recorded "Sunny Afternoon," Shel insisted that Nicky copy my plodding piano style. Other musicians would have been insulted but Nicky seemed to get inside my style, and he played exactly as I would have. No ego. Perhaps that was his secret.[8]

With The Who[]

Hopkins was first invited to join The Who by Shel Talmy in 1965, while recording their debut album My Generation. Due to his ill health, he never performed with the band on stage and appeared only sporadically in the next decade, performing select tracks on Who's Next (1971), before making a full return in 1975 on The Who by Numbers.

Hopkins, given his long association with The Who, was a key instrumentalist on the soundtrack for the 1975 Ken Russell film, Tommy. Hopkins played piano on most of the tracks, and is acknowledged in the album's liner notes for his work on the arrangements for most of the songs.

Solo albums and soundtrack work[]

In 1966, Hopkins released The Revolutionary Piano of Nicky Hopkins, produced by Shel Talmy. Hopkins next solo project released was The Tin Man Was a Dreamer in 1973 under the aegis of producer David Briggs, best known for his work with Neil Young and Spirit. Other musicians appearing on the album include George Harrison (credited as "George O'Hara"), Mick Taylor of the Rolling Stones and Prairie Prince. Re-released by Columbia in 2004, the album features rare Hopkins vocal performances. His second solo album, entitled , was also released in 1975. Appearing on the album are Hopkins (lead vocals and all keyboards), David Tedstone (guitars), Michael Kennedy (guitars), Rick Wills (bass), and Eric Dillon (drums and percussion), with back-up vocals from Kathi McDonald, Lea Santo-Robertie, Doug Duffey and Dolly. A third album, Long Journey Home, has remained unreleased. He also released three soundtrack albums in Japan between 1992 and 1993, The Fugitive, Patio and Namiki Family.

Other groups[]

In 1967, he joined The Jeff Beck Group. Intended as a vehicle for former Yardbirds guitarist Jeff Beck, the band also included vocalist Rod Stewart, bassist Ronnie Wood and drummer Micky Waller.[10] He remained with the ensemble through its dissolution in August 1969, performing on Truth (1968) and Beck-Ola (1969). He also began to record for several San Franciscan groups, including the New Riders of the Purple Sage, the Steve Miller Band and Jefferson Airplane, with whom he recorded the album Volunteers and also performed in the Woodstock Festival. From 1969 to 1970, Hopkins was a full member of Quicksilver Messenger Service, appearing on Shady Grove (1969), Just for Love (1970) and What About Me (1970). In 1975, he contributed to the Solid Silver reunion album as a session musician.

By this point Hopkins was one of Britain's best-known session players, particularly through his work with the Rolling Stones and after playing electric piano on The Beatles' "Revolution" – a rare occasion when an outside rock musician appeared on a Beatles recording. Further raising his profile, he contributed to several Harry Nilsson albums in the early 1970s, including Nilsson Schmilsson and Son of Schmilsson, and recordings by Donovan.

In 1969, Hopkins was a member of the short-lived Sweet Thursday, a quintet comprising Hopkins, Alun Davies (who worked with Cat Stevens), Jon Mark, Harvey Burns and Brian Odgers. The band completed their eponymous debut album; however, the project was doomed from the start. Their American record label, Tetragrammaton Records, abruptly declared bankruptcy[11][12] (by legend, the same day the album was released)[13] with promotion and a possible tour never happening.

In August 1975, he joined the Jerry Garcia Band, envisaged as a major creative vehicle for the guitarist during the mid-seventies hiatus of the Grateful Dead. His increasing use of alcohol precipitated several erratic live performances, resulting in him leaving the group by mutual agreement after a December 31 appearance.[14] During 1979-1989, he was playing and touring with Los Angeles-based Night, who had a hit with a cover of Walter Egan's "Hot Summer Nights". In addition to recording with the Beatles in 1968, Hopkins worked with each of the four when they went solo. Between 1970 and 1975, he appeared on many projects by John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, making key contributions to their critically acclaimed respective solo albums Imagine, Living in the Material World and Ringo. He worked only once with Paul McCartney, on the latter's 1989 album Flowers in the Dirt.

Hopkins also performed with Graham Parker's backing band the Rumour after their keyboardist Bob Andrews left the band.[15]

Later life[]

Hopkins lived in Mill Valley, California, for several years. During this time he worked with several local bands and continued to record in San Francisco. One of his complaints throughout his career was that he did not receive royalties from any of his recording sessions, because of his status at the time as merely a "hired hand", as opposed to pop stars with agents. He received songwriting credit for his work with the Jeff Beck Group, including an instrumental, "Girl From Mill Valley", on the 1969 album Beck-Ola. His precarious health, a consequence of Crohn's disease and its complications, made touring very difficult, limiting him largely to brilliant studio work. Only Quicksilver Messenger Service, through its manager Ron Polte, who went to great lengths to treat his musicians fairly, as well as with assent of the band's members, included Hopkins in an ownership stake.[16] Towards the end of his life Hopkins worked as a composer and orchestrator of film scores, with considerable success in Japan.

In the early 1980s, Hopkins credited the Church of Scientology-affiliated Narconon rehabilitation program with vanquishing his drug and alcohol addictions; he ultimately remained a Scientologist for the rest of his life.[17] As a result of his religious affiliation, he contributed to several of L. Ron Hubbard's musical recordings.

Death[]

Hopkins died on 6 September 1994, at the age of 50, in Nashville, Tennessee, from complications resulting from intestinal surgery related to his lifelong battle with Crohn's disease. At the time of his death, he was working on his autobiography with Ray Coleman.[18]

Legacy and recognition[]

Songwriter and musician Julian Dawson collaborated with Hopkins on one recording, the pianist's last, in spring 1994, a few months before his death. After Ray Coleman's death, the connection led to Dawson working on a definitive biography of Hopkins, first published by Random House in German in 2010, followed in 2011 by the English-language version with the title And on Piano … Nicky Hopkins (a hardback in the UK via Desert Hearts, and a paperback in North America via Backstage Books/Plus One Press).

On 8 September 2018, the Nicky Hopkins "piano" park bench memorial, crowdfunded through PledgeMusic, was unveiled in Perivale Park near Hopkins' birthplace.[19] The campaign offered the opportunity for pledgers to have their name inscribed on the bench and contribute towards funding a music scholarship at London’s Royal Academy of Music, where Hopkins himself won a scholarship in the 1950s. Names that have pledged in the campaign include Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Charlie Watts, Ronnie Wood, Bill Wyman, Yoko Ono Lennon, Roger Daltrey, Jimmy Page, Hossam Ramzy, Johnnie Walker and Kenney Jones. A quote about Hopkins by Bob Harris appears on the bench.[20][21]

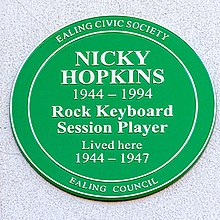

On what would have been Hopkins's 75th birthday (24 February 2019), the Nicky Hopkins Scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music was created, and on 19 October 2019, a commemorative plaque on his childhood home, 38 Jordan Road, Perivale, donated by the , was unveiled.[22] [23]

Discography[]

Solo albums[]

- The Revolutionary Piano of Nicky Hopkins (1966, Produced by Shel Talmy)

- The Tin Man Was a Dreamer (1973)

- (1975)

- Long Journey Home (unreleased)

Soundtracks[]

- The Fugitive (1992)

- Patio (1992)

- Namiki Family (1993)

Selected performances[]

- The Kinks, The Kink Kontroversy (1965), Face to Face (1966), Something Else by The Kinks (1967) and The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (1968).

- The Who, My Generation (1965), "The Song Is Over" and "Getting in Tune" of Who's Next (1971), The Who by Numbers (1975)

- The Rolling Stones, "We Love You" (1967), also "In Another Land" and "She's a Rainbow" of the Their Satanic Majesties Request album (1967); "Sympathy for the Devil" (1968), "Street Fighting Man" (1968), "Gimme Shelter" (1969), "Monkey Man" (1969), "Sway" (1971); "Tumbling Dice" and many others on Exile on Main St. album (1972); "Angie" (1973), "Time Waits for No One" (1974), "Fool to Cry" (1976), "Waiting on a Friend" (recorded 1972, released 1981)

- Jeff Beck, "Blues De Luxe", "Morning Dew" (1967), Truth (1967), and Hopkins's own self-penned "Girl From Mill Valley", on Beck-Ola (1969)

- Cat Stevens, "Matthew and Son" of the Matthew and Son album (1967).

- The Easybeats, "Heaven & Hell", and an unreleased album titled Good Times (1967)[24]

- The Beatles, "Revolution" (single version) (1968)

- Jackie Lomax, "Sour Milk Sea" (1968)[25]

- The Move, "Hey Grandma", "Mist on a Monday Morning", "Wild Tiger Woman" (all 1968)

- The Raisins, "Sahara", "Under the Plump Pears" (1968)

- Jefferson Airplane, "Volunteers" (1969), "Wooden Ships" (1969), "Eskimo Blue Day" (1969), "Hey Fredrick" (1969), whole Woodstock Festival set.

- Steve Miller Band, "Kow Kow", "Baby's House" (which Hopkins co-wrote with Miller) (1969)

- Donovan, "Barabajagal" (1969)

- Quicksilver Messenger Service, Shady Grove (composer of "Edward, the Mad Shirt Grinder") (1969), Just for Love (1970) and What About Me (composer of "Spindrifter") (1970)

- P. J. Proby, Reflections of Your Face (Amory Kane) from "Three Week Hero" (1969)

- The Iveys, See-Saw Granpa (Pete Ham) from Maybe Tomorrow (1969)

- John Lennon, "Jealous Guy", "How Do You Sleep?" and "Oh Yoko!" of Imagine album ( 1971 ), "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" (1971); Walls and Bridges album (1974).

- New Riders of the Purple Sage, Powerglide (1972)

- Carly Simon, No Secrets (1972)

- Jamming with Edward (jam session with Ry Cooder, Mick Jagger, Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts (recorded 1969, released 1972)

- Harry Nilsson, Son of Schmilsson (1972)

- George Harrison, "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)" (1973),[26] Living in the Material World album (1973)

- Ringo Starr, "Photograph" (1973), "You're Sixteen" (1973), "No No Song" (1974)

- Joe Cocker, "You Are So Beautiful" (1974)

- Marc Bolan, "Jasper C. Debussy" (recorded 1966–67, released 1974)

- Peter Frampton, "Waterfall" and "Sail Away" from Somethin's Happening (1974)

- Jerry Garcia Band, Let It Rock: The Jerry Garcia Collection, Vol. 2 (1975), Garcia Live Volume Five (1975)

- Jerry Garcia, Reflections (1976)

- Art Garfunkel, Breakaway (1975)

- Rod Stewart, "You're in My Heart (The Final Acclaim)" (1977)

- Badfinger, "Airwaves" (1979)

- Graham Parker, Another Grey Area (1982)

- Paul McCartney, "That Day Is Done" (1989)

- The Dogs D'Amour, "Hurricane", "Trail of Tears", and "Princes Valium" from the Errol Flynn/King of the Thieves album (1989)

- Spinal Tap, "Rainy Day Sun" on the Break like the Wind album (1991)

- The Jayhawks, "Two Angels" and "Martin's Song"[27] on the Hollywood Town Hall album (1992)

- Joe Walsh, "Guilty of the Crime" from the album A Future to This Life: Robocop – The Series Soundtrack (1994)

- Gene Clark (various recordings)

- Brewer & Shipley

- Izzy Stradlin and the Ju Ju Hounds (album)

- Additional Amory Kane works

Collaborations[]

With Art Garfunkel

- Breakaway (Columbia Records, 1975)

- Lefty (Columbia Records, 1988)

With Carly Simon

- No Secrets (Elektra Records, 1972)

With Ronnie Wood

- 1234 (Columbia Records, 1981)

With Peter Frampton

- Somethin's Happening (A&M Records, 1974)

With Jackie Lomax

- Is This What You Want? (Apple Records, 1969)

With Martha Reeves

- Martha Reeves (MCA Records, 1974)

With Donovan

- Essence to Essence (Epic Records, 1973)

With Joe Cocker

- I Can Stand a Little Rain (A&M Records, 1974)

- Jamaica Say You Will (A&M Records, 1975)

With Paul McCartney

- Flowers in the Dirt (Parlophone Records, 1989)

With Belinda Carlisle

- Belinda (I.R.S. Records, 1986)

With Rod Stewart

- Foot Loose & Fancy Free (Warner Bros. Records, 1977)

- Blondes Have More Fun (Warner Bros. Records, 1978)

- Every Beat of My Heart (Warner Bros. Records, 1986)

With Bill Wyman

- Stone Alone (Atlantic Records, 1976)

With Matthew Sweet

- Altered Beast (Zoo Entertainment, 1993)

With Ringo Starr

- Ringo (Apple Records, 1973)

- Goodnight Vienna (Apple Records, 1974)

With Dusty Springfield

- White Heat (Casablanca Records, 1982)

With George Harrison

- Living in the Material World (Apple Records, 1973)

- Dark Horse (Apple Records, 1974)

- Extra Texture (Read All About It) (Apple Records, 1975)

With Carl Wilson

- Youngblood (Caribou Records, 1983)

With Carole Bayer Sager

- Carole Bayer Sager (Elektra Records, 1977)

With Jennifer Warnes

- Jennifer Warnes (Arista Records, 1977)

With Harry Nilsson

- Son of Schmilsson (RCA Records, 1972)

With John Lennon

- Imagine (Apple Records, 1971)

- Walls and Bridges (Apple Records, 1974)

With Adam Bomb

- New York Times (Hopkins played on "NY Child" "Cheyenne" "Heaven Come to me") produced by Jack Douglas recorded in 1990 & published in 2001

References[]

- ^ Welch, Chris (9 September 1994). "Obituary: Nicky Hopkins". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Dawson, Julian (2011). And On Piano...Nicky Hopkins. Desert Hearts. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-898948-12-4.

- ^ "Homage to Wembley session musician who played with The Beatles. – What's on – Brent & Kilburn Times". Kilburntimes.co.uk. 3 June 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Nicky Hopkins - Biography". Nickyhopkins.com. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Janovitz, Bill (2014). Rocks Off: 50 Tracks That Tell the Story of the Rolling Stones. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-857-90790-5.

- ^ "Hopkins Forsakes Studios For Solo". Billboard: 21. 16 June 1973. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ Bodganov, Vladimir; et al. (2003). All Music Guide to the Blues (3rd ed.). Backbeat Books. p. 140. ISBN 0-87930-736-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ray Davies on Nicky Hopkins, from The New York Times, on January 1, 1995". Kindakinks.net. 1 January 1995. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Dawson, Julian (2011). And on Piano … Nicky Hopkins. Backstage Press. pp. 82–83

- ^ Hoffmann, Frank W. (ed.) (rev. 2005). Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound, p. 83. CRC Press. ISBN 0-415-93835-X

- ^ |Callahan, Mike; Eyries, Patrice & Edwards, Dave (25 March 2008). "Tetragrammaton Album Discography". Both Sides Now Publications. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Deep Purple [1969]: Review". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ George-Warren, Holly; Romanowski, Patricia; Pareles, Jon, eds. (2001). The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (3rd ed.). Fireside Books. p. 608. ISBN 0-7432-0120-5.

- ^ Jackson, Blair (2000). Garcia: An American Life, pp. 269–70. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-029199-7.

- ^ Cabin, Geoff. "The Musical Obsessions of Andrew Bodnar". Rock Beat International. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Quicksilver Messenger Service manager Ron Polte dies in Mill Valley at 84, Marin Independent Journal, Paul Liberatore, September 16, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Book Review: and on the piano..Nicky Hopkins-The Life of Rock's Greatest Session Man". Nodepression.com. 30 September 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (10 September 1994). "Nicky Hopkins, 50, Studio Keyboardist In Rock Recording". The New York Times. p. 26. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Musical memorial unveiled for keyboard star Nicky Hopkins". Ealing News Extra. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ Richards, Sam (7 September 2018). "Memorial unveiled to rock pianist Nicky Hopkins". Uncut Magazine. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ Miller, Frederica (23 May 2018). "This brilliant but forgotten Ealing rocker played with The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and David Bowie". Get West London. p. 26. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Cann, Ged (24 September 2019). "We bet you can't name the Ealing pianist who played with The Beatles". My London. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ "Green Plaque Unveiled For Ealing Musician". London: EalingToday.co.uk. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "MILESAGO – The Easybeats". Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8), p. 206.

- ^ Leng, Simon (2006). While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, p. 126. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 1-4234-0609-5.

- ^ Drakoulias, George (2011). Hollywood Town Hall (booklet). The Jayhawks. American Recordings. pp. 9–11. 88697 72731 2.

External links[]

- 1944 births

- 1994 deaths

- English rock keyboardists

- English rock pianists

- English session musicians

- Quicksilver Messenger Service members

- Plastic Ono Band members

- British expatriates in the United States

- People from Harlesden

- English organists

- British male organists

- Fontana Records artists

- 20th-century British pianists

- 20th-century English musicians

- Steve Miller Band members

- All-Stars (band) members

- Screaming Lord Sutch and the Savages members

- English Scientologists

- People with Crohn's disease

- Cliff Bennett and the Rebel Rousers members

- Jerry Garcia Band members

- Lord Sutch and Heavy Friends members

- 20th-century British male musicians