No man's land

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

No man's land is waste or unowned land or an uninhabited or desolate area[1] that may be under dispute between parties who leave it unoccupied out of fear or uncertainty. The term was originally used to define a contested territory or a dumping ground for refuse between fiefdoms.[2] In modern times, it is commonly associated with World War I to describe the area of land between two enemy trench systems, not controlled by either side.[3][1] The term is also used metaphorically, to refer to an ambiguous, anomalous, or indefinite area, in regards to an application, situation,[4] or jurisdiction.[5][6] It has sometimes been used to name a specific place.[1]

Origin[]

According to Alasdair Pinkerton, an expert in human geography at Royal Holloway, University of London, the term is first mentioned in Domesday Book in the 11th century, to describe parcels of land that were just beyond the London city walls.[7] The Oxford English Dictionary contains a reference to the term dating back to 1320, spelled nonesmanneslond, to describe a territory that was disputed or involved in a legal disagreement.[1][2][8] The same term was later used as the name for the piece of land outside the north wall of London that was assigned as the place of execution.[8] The term is also applied in nautical use to a space amidships, originally between the forecastle and the booms in a square-rigged vessel where various ropes, tackle, block, and other supplies were stored.[1][9] In the United Kingdom, several places called No Man's Land denoted "extra-parochial spaces that were beyond the rule of the church, beyond the rule of different fiefdoms that were handed out by the king … ribbons of land between these different regimes of power".[7]

Examples[]

World War I[]

The British Army did not widely employ the term when the Regular Army arrived in France in August 1914, soon after the outbreak of World War I.[10] The terms used most frequently at the start of the war to describe the area between the trench lines included 'between the trenches' or 'between the lines'.[10] The term 'no man's land' was first used in a military context by soldier and historian Ernest Swinton in his short story "The Point of View".[2] Swinton used the term in war correspondence on the Western Front, with specific mention of the terms with respect to the Race to the Sea in late 1914.[10] The Anglo-German Christmas truce of 1914 brought the term into common use, and thereafter it appeared frequently in official communiqués, newspaper reports, and personnel correspondences of the members of the British Expeditionary Force.[10]

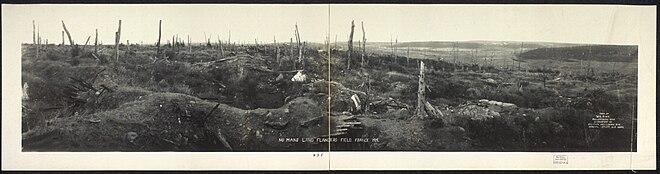

In World War I, no man's land often ranged from several hundred yards to in some cases less than 10 yards.[11] Heavily defended by machine guns, mortars, artillery, and riflemen on both sides, it was often extensively cratered, and was riddled with barbed wire, rudimentary improvised land mines, as well as corpses and wounded soldiers who were unable to make it through the hail of bullets, explosions, and flames. The area was sometimes contaminated by chemical weapons. It was open to fire from the opposing trenches and hard going generally slowed any attempted advance.

Not only were soldiers forced to cross no man's land when advancing, and as the case might be when retreating, but after an attack the stretcher bearers had to enter it to bring in the wounded. No man's land remained a regular feature of the battlefield until near the end of World War I, when mechanised weapons (i.e., tanks) made entrenched lines less of an obstacle.

Effects from World War I no man's lands persist today, for example at Verdun in France, where the Zone Rouge (Red Zone) contains unexploded ordnance, and is poisoned beyond habitation by arsenic, chlorine, and phosgene. The zone is sealed off completely and still deemed too dangerous for civilians to return: "The area is still considered to be very poisoned, so the French government planted an enormous forest of black pines, like a living sarcophagus", comments Alasdair Pinkerton, a researcher at Royal Holloway University of London, who compared the zone to the nuclear disaster site at Chernobyl, similarly encased in a "concrete sarcophagus".[7]

Cold War[]

During the Cold War, one example of "no man's land" was the territory close to the Iron Curtain. Officially the territory belonged to the Eastern Bloc countries, but over the entire Iron Curtain there were several wide tracts of uninhabited land, several hundred meters in width, containing watch towers, minefields, unexploded bombs, and other such debris. Would-be escapees from Eastern Bloc countries who successfully scaled the border fortifications could still be apprehended or shot by border guards in the zone.

The U.S. Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba is separated from Cuba proper by an area called the Cactus Curtain. In late 1961, the Cuban Army had its troops plant an 8-mile (13 km) barrier of Opuntia cactus along the northeastern section of the 28-kilometre (17 mi) fence surrounding the base to prevent economic migrants fleeing from Cuba from resettling in the United States.[12] This was dubbed the "Cactus Curtain", an allusion to Europe's Iron Curtain[13] and the Bamboo Curtain in East Asia. U.S. and Cuban troops placed some 55,000 land mines across the no man's land, creating the second-largest minefield in the world, and the largest in the Americas. On 16 May 1996, President Bill Clinton ordered the U.S. land mines to be removed and replaced with motion and sound sensors to detect intruders. The Cuban government has not removed the corresponding minefield on its side of the border.[citation needed]

Israel–Jordan[]

The 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and Transjordan were signed in Rhodes with the help of UN mediation on 3 April 1949.[14] Armistice lines were determined in November 1948. Between the lines territory was left that was defined as no man's land.[15][16] Such areas existed in Jerusalem in the area between the western and southern parts of the Walls of Jerusalem and Musrara.[17] A strip of land north and south of Latrun was also known as "no man's land" because it was not controlled by either Israel or Jordan in 1948–1967.[18]

Current no man's land[]

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone was established between North Korea and South Korea at the end of the Korean War in 1953.

- The Agreement on Disengagement signed by Israel and Syria after the Yom Kippur War in 1974 established a United Nations Disengagement Observer Force-patrolled buffer zone in the Golan Heights, including Quneitra.

- United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus (The Green Line) and abandoned Varosha has acted as a no man's land between Cyprus and Turkish-occupied Northern Cyprus since 1974.

See also[]

References[]

- Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "no man's land". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. 256795. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Persico p. 68

- ^ Coleman p. 268

- ^ "No-man's land definition and meaning". www.collinsdictionary.com.

- ^ "Definition of NO-MAN'S-LAND". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ "Portraits of No-Man's-Land". artsandculture.google.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Adventures in No Man's Land". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levenback p. 95

- ^ Hendrickson, Robert Facts on File Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins (2008)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Payne, David (8 July 2008). "No Man's Land". Western Front Association. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ Hamilton, John (2003), Trench Fighting of World War I, ABDO, p. 8, ISBN 1-57765-916-3

- ^ "Guantanamo Bay Naval Base and Ecological Crises". Trade and Environment Database. American University. Archived from the original on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ "Yankees Besieged". TIME. 1962-03-16. Archived from the original on 2010-08-28.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2017-06-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2012-09-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-09-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Hasson, Nir (30 October 2011). "Reclaiming Jerusalem's No-man's-land". Archived from the original on 9 February 2014 – via Haaretz.

- ^ "Palestinians for Peace and Democracy". www.p4pd.org. Archived from the original on 2014-11-11.

- Bibliography

- Coleman, Julie (2008). A History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries. 3. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-954937-0.

- Persico, Joseph E. (2005). Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918 World War I and Its Violent Climax. Random House. ISBN 0-375-76045-8.

- Land warfare

- Metaphors referring to places

- Territorial disputes

- Trench warfare