Noronha skink

| Noronha skink | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Trachylepis |

| Species: | T. atlantica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Trachylepis atlantica (Schmidt, 1945)

| |

| |

| Location of Fernando de Noronha, the island to which the Noronha skink is endemic.[2] | |

| Synonyms[fn 8] | |

| |

The Noronha skink[13] (Trachylepis atlantica) is a species of skink from the island of Fernando de Noronha off northeastern Brazil. It is covered with dark and light spots on the upperparts and is usually about 7 to 10 cm (3 to 4 in) in length. The tail is long and muscular, but breaks off easily. Very common throughout Fernando de Noronha, it is an opportunistic feeder, eating both insects and plant material, including nectar from the Erythrina velutina tree, as well as other material ranging from cookie crumbs to eggs of its own species. Introduced predators such as feral cats prey on it and several parasitic worms infect it.

Perhaps seen by Amerigo Vespucci in 1503, it was first formally described in 1839. Its subsequent taxonomic history has been complex, riddled with confusion with Trachylepis maculata and other species, homonyms, and other problems. The species is classified in the otherwise mostly African genus Trachylepis and is thought to have reached its island from Africa by rafting. The enigmatic Trachylepis tschudii, supposedly from Peru, may well be the same species.

Discovery and taxonomy[]

In an early account of what may be Fernando de Noronha, purportedly based on a voyage by Amerigo Vespucci in 1503, the island was said to be inhabited by "lizards with two tails", which is thought be a reference to the Noronha skink.[14] The tail is long and fragile, and it breaks easily, like that of many skinks and other lizards, following which it may regenerate. However, when it does not completely break off, a new tail may nevertheless grow out of the broken part, so that the tail appears forked.[14]

19th century[]

The species was first formally described by John Edward Gray in 1839,[3] based on two specimens collected by HMS Chanticleer before 1838.[15] He introduced the names Tiliqua punctata, for the Noronha skink, and Tiliqua maculata, for a species from Guyana, among many others.[3] Six years later, he transferred both to the genus Euprepis.[5] In 1887, George Boulenger placed both in the genus Mabuya (misspelled "Mabuia") and considered them identical, using the name "Mabuia punctata" for the species, which was said to occur both on Fernando de Noronha and in Guyana. He also included Mabouya punctatissima O'Shaughnessy, 1874, purportedly from South Africa, as a synonym.[16] In 1874, A.W.E. O'Shaughnessy described the new species Mabouya punctatissima on the basis of a specimen, purchased from a Mr. Parzudaki, which had been labeled as coming from the Cape of Good Hope, a location O'Shaughnessy considered "very doubtful".[17] G.A. Boulenger, in 1887 synonymized it under Mabuia punctata (the Noronha skink) without comment,[7] a position followed by H. Travassos with some doubt. The latter wrote that the description of punctatissima suggested to him that punctatissima and the Noronha skink are morphologically different, but that Boulenger's examination of the type and the uncertainty of the type locality inclined him to favor the synonymy.[18] In 2002, P. Mausfeld and D. Vrcibradic re-examined the holotype, which is the only known specimen. It is similar to T. atlantica, but larger, and lacks well-developed keels on its dorsal scales. Therefore, they suggested that it was not the same as T. atlantica and that its original locality may have been correct. Although it may represent a valid species of southern African Trachylepis, the name Trachylepis punctatissima is preoccupied by Euprepes punctatissimus A. Smith, 1849, also currently placed in Trachylepis.[19]

20th century[]

In 1900, L.G. Andersson claimed that Gray's name punctata was preoccupied by Lacerta punctata Linnaeus, 1758, which he identified as . He therefore replaced the name punctata with its junior synonym maculata, using the name Mabuya maculata for the skink of Fernando de Noronha.[20] Linnaeus's Lacerta punctata in fact refers to the Asian species , not to Mabuya homalocephala, but Gray's name punctata remains invalid regardless.[21] In 1931, C.E. and M.D. Burt resurrected the name Mabuya punctata (now spelled correctly) for the Noronha skink, noting that it was "apparently a very distinct species", but did not mention maculata,[9] and in 1935, E.R. Dunn disputed Boulenger's conclusion as to the synonymy of punctata and maculata and, in apparent ignorance of Andersson's work, restored the name Mabuya punctata for the Noronha skink.[22] He wrote that the Noronha skink was very distinct from other American Mabuya and more similar in some respects to African species.[23]

Karl Patterson Schmidt, in 1945, agreed with Dunn's conclusion that maculata and punctata of Gray were not the same, but he noted Andersson's point that punctata was preoccupied and therefore introduced the new name Mabuya atlantica to replace punctata.[10] The next year, H. Travassos, disagreeing with Dunn and unaware of Andersson's and Schmidt's contributions,[24] considered both of Gray's names to be synonymous and restored the name Mabuya punctata for the Noronha skink.[25] He also considered Mabouya punctatissima and Trachylepis (Xystrolepis) punctata Tschudi, 1845, described from Peru, as synonyms of this species.[26] In 1948, he acknowledged the preoccupation of punctata noted by Andersson and accordingly retired Mabuya punctata in favor of Mabuya maculata, as Andersson had done.[27] The name Mabuya maculata remained in general usage for the Noronha skink in subsequent decades, though some have used Mabuya punctata, "not ... aware of the last nomenclatural changes."[20]

21st century[]

In 2002, P. Mausfeld and D. Vrcibradic published a note on the nomenclature of the Noronha skink informed by a re-examination of Gray's original type specimens; despite extensive attempts to correctly name the species, they were apparently the first to do so since Boulenger in 1887.[28] Based on differences in the number of scales, (lamellae on the lower sides of the digits), and keels (longitudinal ridges) on the dorsal scales (located on the upperparts), as well as the separation of the parietal scales (on the head behind the eyes) in maculata,[28] they concluded that the two were not, after all, identical, and that Schmidt's name Mabuya atlantica should therefore be used.[19] Mausfeld and Vrcibradic considered Mabouya punctatissima to represent a different species on the basis of morphological differences,[28] but were unable to resolve the status of Trachylepis (Xystrolepis) punctata.[20]

In the same year, Mausfeld and others conducted a molecular phylogenetic study on the Noronha skink, using the mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA genes, and showed that the species is more closely related to African than to South American Mabuya species,[29] as previously suggested on the basis of morphological similarities.[30] They split the old genus Mabuya into four genera for geographically discrete clades, including Euprepis for the African–Noronha clade, thus renaming the Noronha species to Euprepis atlanticus.[11] In 2003, A.M. Bauer found that the name Euprepis had been incorrectly applied to this clade and that Trachylepis was correct instead, so that the Noronha skink is currently referred to as Trachylepis atlantica.[31][fn 6] Additional molecular phylogenetic studies published in 2003 and 2006 confirmed the relationship between the Noronha skink and African Trachylepis.[32]

In 2009, Miralles and others reviewed the taxon maculata and concluded that the animal now known as Trachylepis maculata also belongs in the African clade, but they were unable to determine whether or not it is indigenous to Guyana.[33] They also reviewed Trachylepis (Xystrolepis) punctata and replaced it with Trachylepis tschudii because the older name was preoccupied by Linnaeus's and Gray's punctata.[12] Although they were unable to resolve the identity of T. tschudii, which is still known from a single specimen, they believed that it is most likely the same species as the Noronha skink; it may be either a representative of an undiscovered Amazonian population of the latter or simply a mislabeled animal from Fernando de Noronha.[34]

Description[]

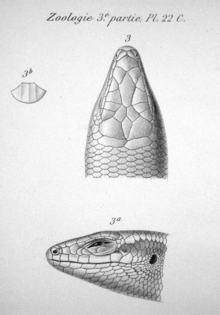

The Noronha skink is thought to be about 7–10 cm in length; it is covered with light and dark spots and the skinks vary in color. While there are no longitudinal stripes, there can be detailed patterning on their backs and stomachs as well. Their underbelly contains yellowish or grayish scales. The eyelids also range from white to yellow. The scales on this species are known to be different at various locations on the skinks body. Its tail is long and muscular and has the ability to break off and regrow.

Its overall head shape is small, and the layout of its face is interesting as its nostrils are towards the lateral parts of its head. The mouth contains a small set of teeth and its tongue is thin. This skink is known for its ground foraging capabilities. It has an extremely broad diet and will eat anything from human leftovers to its own feces or eggs. Occasionally, the skink can be found preying on dead birds or fish. The Noronha skink also tends to climb about 12 m high on mulungu tree’s to eat and pollinate surrounding flowers. This skink is a very opportunistic forager and in turn is extremely versatile.[35] The hindlimbs are longer and stronger than the forelimbs, which are small. The tail is longer than the body and is muscular but very brittle. It is nearly cylindrical in form and tapers towards the end.[36]

In reptiles, features of the scales are important in distinguishing among species and groups of species. In the Noronha skink, the supranasal scales (located above the nose) are in contact, as are the prefrontal scales (behind the nose) in most individuals. The two frontoparietal scales (above and slightly behind the eyes) are not fused. Unlike in T. maculata, the parietal scales (behind the frontoparietals) are in contact with each other. There are four supraocular scales (above the eyes) in almost all specimens and five supraciliary scales (immediately above the eyes, below the supraoculars). The dorsal scales (on the upperparts) have three keels, two fewer than in T. maculata. There are 34 to 40 (mode 38) midbody scales (counted around the body midway between the fore- and hindlimbs), 58 to 69 (mode 63–64) dorsal, and 66 to 78 (mode 70) ventral scales (on the underparts).[37] Mabuya species and T. maculata generally have fewer midbody scales (up to 34).[38] There are 21 to 29 subdigital lamellae under the fourth toe, more than in T. maculata, which has 18.[39] The Noronha skink has 26 (located before the sacrum), similar to most Trachylepis, but unlike American Mabuya, which have at least 28.[40]

Although there is substantial variation in measurements within the species, no discrete groups can be detected and it is not possible to separate the sexes unambiguously using measurements alone.[41] Among 15 male and 21 female T. atlantica collected in 2006, snout to vent length was 80.6 to 103.1 mm (3.17 to 4.06 in), averaging 95.3 mm (3.75 in), in males and 65.3 to 88.1 mm (2.57 to 3.47 in), averaging 78.3 mm (3.08 in), in females and body mass was 10.2 to 26.0 g (0.36 to 0.92 oz), averaging 19.0 g (0.67 oz), in males and 6.0 to 15.0 g (0.21 to 0.53 oz), averaging 10.0 g (0.35 oz), in females. Males are significantly larger than females.[42] In 100 specimens collected in 1876,[43] head length was 12.0 to 18.9 mm (0.47 to 0.74 in), averaging 14.8 mm (0.58 in); head width was 7 to 14.4 mm (0.28 to 0.57 in), averaging 9 mm (0.35 in), and tail length was 93 to 170 mm (3.7 to 6.7 in), averaging 117 mm.[39][fn 9]

Origin[]

It is unclear exactly where the skink originated from and it is believed that their classification could be incorrect to this day. Phylogenetic analyses, including those of mitochondrial and nuclear gene analysis, has determined that the Noronha skink is a descendant of the African species Trachylepis. Morphological similarities also support this. It is thought that the skink could have arrived the Fernando de Noronha archipelago via rafting on vegetation from southwestern Africa via the current of Benguela and the Southern Equatorial current. Alfred Russel Wallace suggested this hypothesis in 1888. The journey from Africa to Fernando de Noronha would take approximately 139 days. This seems like too long of a period for the skink to survival and so it is more likely that the skink floated from island to island; thus, their origin is unclear, but they clearly date back to historical times. The South American and Caribbean Mabuya skinks also form a clade derived from Africa as well. Transatlantic colonization events in Africa that are mentioned are believed to have occurred within the last 9 million years.

In early accounts of Fernando de Noronha, purportedly based on a voyage led by Amerigo Vespucci in 1503, the island was said to possibly inhabited by a “lizards with two tails”, which may be referencing the Noronha skink. The tail was described as extremely long and fragile. Similar to other lizards, the tail revealed regenerative abilities. However, if the tail is not completely broken off and only part is remaining, then the new tail may grow from the broken piece. Thus, this potentially forking and explaining the two tailed phenomenon described above.

Habitat[]

The Noronha skink is endemic to an Archipelago off Northeast Brazil, entitled Fernando de Noronha. It is the most abundant terrestrial vertebrate (1). These lizards are found to prefer desert habitats, and this drastically affects their food preferences. Fernando de Noronha is known for lacking predators of these skinks, thus explaining their high abundance(1). The skinks also bury in the rocks of this desert habitat. Although nocturnal, during the day they can be found climbing, basking in the sun, and laying on rocks. The Noronha skink is also found in human dwellings and inside peoples homes. (2) Most commonly, this skink is found on the ground, however, they are also capable of climbing. As Fernando de Noronha has a dry season, it is known that the skinks avoid reproductive activities during this period.

The Noronha archipelago belongs to the Brazilian state of Pernambuco and is in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 21 volcanic islands and the climate, as previously state, varies between dry and wet seasons, but is overall classified as tropical. It is also known for being a UNESCO world heritage site and is home to several endemic reptiles and species of birds.

The species is thought to have a body temperature around 90 degrees Fahrenheit, which is a few degrees higher than the typical environmental temperature. During the day, however, the body temperature can peak up to 100 degrees and then lower as the sun goes down. The lizard is most commonly found basking in the early morning. During the act of foraging, the lizard is thought to move about 28.4% of the time which indicates it is one of the more active lizards of its family (28.4% is very high).

Diet[]

The Noronha skink is an opportunistic omnivore[45] and "thrives on anything edible".[35] Analysis of stomach contents indicates that it mainly eats plant material, at least during the dry period,[46] but it also feeds on insects, including larvae, termites (Isoptera), ants (Formicidae), and beetles (Coleoptera).[42] Its prey is mostly mobile, rather than sedentary,[47] which is consistent with the relatively high proportion of time it spends moving.[48] Related skink species eat mostly insects, but island populations may often be more herbivorous. Animal prey averages 6.9 mm3 in volume, less than in most other Trachylepis.[46]

When the mulungu tree Erythrina velutina blooms during the dry season, Noronha skinks climb up to 12 m (39 ft) to reach the inflorescences of the tree and to eat the nectar by inserting their heads into the flowers.[35] They probably use the nectar both for its sugar and water content.[49] In this way, the skinks aid in pollinating the tree, as they acquire pollen on their scales and leave pollen on stigmas when visiting a flower.[50] Pollination is rare behavior among lizards, but occurs most frequently in island species.[35] Humans have introduced additional food sources to the island, including Acacia seeds, feces of the rock cavy (Kerodon rupestris), carrion flies, juvenile Hemidactylus mabouya, and even cookie crumbs given by tourists.[51] The availability of these additional food sources may increase the abundance of the skink.[52] In 1887, H. N. Ridley observed Noronha skinks eating banana skins and yolk from doves' eggs.[53] Several cases of cannibalism have been reported, involving skinks eating eggs, juveniles, and the tail of an adult.[54]

Noronha Skinks eat a wide variety of foods, partially contributing to their large presence on the island. They are commonly found to consume arthropods, conspecific eggs, human leftovers, plant materials, and dead vertebrates. Because of their dry desert habitat, when food sources like arthropod’s are scarce, skinks increase their plant intake. Dry season offers prime intraspecific competition for resources until new resources emerge. Occasionally, the skink will eat its own feces as well if needed.

Ecology and behavior[]

The Noronha skink is very abundant throughout Fernando de Noronha,[55] even occurring commonly in houses,[57] and also occurs on the smaller islands that surround the main island of the archipelago.[58] Its abundance may be a result of the absence of ecologically similar competitors.[59] Apart from T. atlantica, the reptile fauna of Fernando de Noronha consists of the indigenous amphisbaenian Amphisbaena ridleyi and two introduced lizards, the gecko Hemidactylus mabouia and the tegu Tupinambis merianae.[2]

The species is found in several microhabitats, but most often on rocks.[56] Although predominantly ground-dwelling, it is a good climber.[49]

Trachylepis atlantica is active during the day. Its body temperature averages 32 °C (90 °F), a few degrees higher than the environment temperature. During the day, body temperature peaks at up to 38 °C (100 °F) around midday and is lower earlier and later. In the early morning, the lizard may bask in the sun. During foraging, it spends about 28.4% of its time moving on average, a relatively high value for Trachylepis.[56] A geologist who visited the island in 1876[60] noted that the skink is curious and bold: While seated upon the bare rocks I have often observed these little animals watching me, apparently with as much curiosity as I watched them, turning their heads from side to side as if in an effort to be wise. If I kept quiet for a few minutes they would creep up to me and finally upon me; if I moved, they ran down the faces of the rocks, and turning, stuck their heads above the edges to watch me.[61]

Intraspecific Competition[]

Because these lizards are thought to have no predators, this implies high levels of intraspecific competition; the competition is over food resources, habitat occupation, and mating. The intraspecific competition also contributes to the broad diet of the skink. The skinks have been found to chase and prey on other lizards, such as the House gecko, especially in the dry season. These geckos are often found on the ground and low branches. These skinks display the unique behavior of pollinating flowers. This is an extremely rare trait in lizards. The skink was found to seek nectar in flowers of the leguminous mulungu tree at Fernando de Noronha Archipelago. This is a tree that blossoms during the dry season and the flower’s nectar is filled with nutrients. The pollen from the flowers is thought to stick to the Noronha skink’s scales and this is how it spreads the pollen (somewhat incidentally). The scales of the skink will rub on the anthers or stigmas of other flowers, causing the act of pollination.[49] It is thought that the skink pursues these flowers for energy purposes, diluted sugars, and water content purposes.

Reproduction[]

Noronha Skinks nest in logs and trees. Their nests are often confined. Eggs may stick together within a nest. These eggs are somewhat elongated from a spherical shape, with their size ranging about 16–18mm wide and 29–33mm high. After hatching, the skinks have the same coloration as and similar appearance to the adult skinks. Females are thought to lay 15–18 eggs in each clutch. This skink is known to practice sexual reproduction but means of courtship and mating are yet to be researched and determined. It is thought that the intraspecific competition may relate to mating tactics utilized by males. Survival rates during incubation and shortly afterward are also unclear, but it is thought that between 8–11 of the 15-18 eggs laid actually hatch and survive.

Nothing is known about its reproduction except that skinks studied in late October and early November, during the dry season, showed little evidence of reproductive activity.[62] The Noronha skink is oviparous (egg-laying), like many Trachylepis,[11] but unlike Mabuya, which are all viviparous (giving live birth).[63]

Predators and Parasites[]

The Noronha skink probably lacked predators before Fernando de Noronha was discovered by humans, but several species that arrived since do prey on it,[57] most commonly the cat (Felis catus) and cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis).[45] These may negatively affect skink abundance at some localities on the island, but do not threaten the species with extinction or threatened status.[64] The Argentine black and white tegu lizard, Tupinambis merianae, and three introduced rodents, the house mouse (Mus musculus), brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) and black rat (Rattus rattus), have also been observed to eat Noronha skinks,[54] but the rodents, particularly the house mouse, may have been scavenging on already dead skinks.[45]

According to a 2006 study, the Noronha skink is infected by several parasitic worms, most frequently by the nematode . Another nematode, , is much rarer. Other rare parasites include two trematodes— and an undetermined species of —and an undetermined species of Oochoristica, a cestode.[65] S. spinicauda is usually only found in teiid lizards; it may have entered the archipelago when Tupinambis merianae, a teiid, was introduced to the island[66] in 1960.[65] Among nematodes, previous studies in 1956 and 1957 had only reported M. alvarengai and from the skink; the presence of S. spinicauda could explain the rarity of M. alvarengai and absence of T. alvarengai in Noronha skinks observed in 2006.[66]

Conservation[]

The reptile is thought to be stable in terms of population trends and not under any threat of extinction. However, the climate is rapidly changing, so this could change at any point in time. Although environmental changes do not affect the species in particular, the density of the species is at risk of decreasing should the environment change drastically as well as if tourism trends or more invasive animals are introduced. Additionally, the urbanization of surrounding areas to the lizards habitat could be detrimental.

Interaction with Humans[]

As humans are now able to access more parts of the world than ever before, human interaction with these skinks is complex. Humans have introduced new foods into the Noronha skink’s diet, such as crumbs and trash waste. There are two theories proposed as to how humans have affected the skinks population in Fernando de Noronha. The first hypothesizes that lizard densities were originally low and once humans started to live in the same area and colonize the area, an increase in food resources led to a boom in the skink population. The second states that lizard density was high prior to human presence and this hypothesis is supported by the lack of predators in their habitat.

Noronha skinks lack defensive mechanisms due to the lack of predation in their natural habitat. Therefore, introducing more species into Norohona’s skinks natural habitats may be harmful to the species well being. Human activity is a direct cause of Noronha skinks’ shrinking population, as human’s pets like cats prey on this species. Human activities that contribute to climate change also affect the skinks as the species thrive in tropical climates. Similarly, deforestation poses a danger to the Noronha skinks’ special well-being.

Notes[]

- ^ Preoccupied by Lacerta punctata Linnaeus, 1758 (=).[4]

- ^ Preoccupied by Lacerta punctata Linnaeus, 1758 (=Lygosoma punctatum) and Tiliqua punctata Gray, 1839 (=Trachylepis atlantica).[6]

- ^ Sic. Included maculata Gray and Mabouya punctatissima O'Shaughnessy, 1872, as junior synonyms.[7]

- ^ In error; Mabuya maculata (currently Trachylepis maculata) is a species distinct from Trachylepis atlantica.[8]

- ^ Nomen novum (replacement name) for punctata Gray, 1839, not Linnaeus, 1758.[10]

- ^ a b Bauer, 2003, p. 5, corrected the generic name from Euprepis to Trachylepis, but did not explicitly use the name combination Trachylepis atlantica, which was first used by Ananjeva et al., 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Nomen novum for punctata Tschudi, 1845, not Linnaeus, 1758, or Gray, 1839; identity uncertain (see text).[12]

- ^ In this list of synonyms, new combinations (the first use of a given combination of a genus and species name) are indicated by a colon between the name combination and the authority which first used the combination. No colon is used when the name is entirely new.

- ^ Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, table 1, list the average tail length as 11 mm, an obvious error. The actual average tail length in Travassos's dataset[44] is 117 mm.

References[]

- ^ Colli, G.R., Fenker, J., Tedeschi, L., Bataus, Y.S.L., Uhlig, V.M., Silveira, A.L., da Rocha, C., Nogueira, C. de C., Werneck, F., de Moura, G.J.B., Winck, G., Kiefer, M., de Freitas, M.A., Ribeiro Junior, M.A., Hoogmoed, M.S., Tinôco, M.S.T., Valadão, R., Cardoso Vieira, R., Perez Maciel, R., Gomes Faria, R., Recoder, R., Ávila, R., Torquato da Silva, S., de Barcelos Ribeiro, S. & Avila-Pires, T.C.S. 2019. Trachylepis atlantica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T120689136A134890404. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T120689136A134890404.pt. Downloaded on 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Rocha et al., 2009, p. 450

- ^ a b c Gray, 1839, p. 289

- ^ Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, p. 293; Bauer, 2003, p. 4

- ^ a b Gray, 1845, p. 111

- ^ Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, p. 293; Miralles et al., 2009, p. 57

- ^ a b Boulenger, 1887, p. 160

- ^ Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, pp. 292, 294

- ^ a b Burt and Burt, 1931, p. 302

- ^ a b Schmidt, 1945, p. 45

- ^ a b c Mausfeld et al., 2002, p. 290

- ^ a b Miralles et al., 2009, p. 57

- ^ Rocha et al., 2009, p. 450; Sazima et al., 2005, p. 185–186; Silva et al., 2005, p. 62

- ^ a b Carleton and Olson, 1999, p. 48

- ^ Schmidt, 1945, p. 45; Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, p. 292

- ^ Boulenger, 1887, pp. 160–161

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, 1874, p. 300.

- ^ Travassos, 1946, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, p. 292

- ^ Bauer, 2003, p. 4

- ^ Dunn, 1935, pp. 535–536

- ^ Dunn, 1935, p. 536

- ^ Travassos, 1948, p. 201

- ^ Travassos, 1946, pp. 6–7

- ^ Travassos, 1946, pp. 7–8

- ^ Travassos, 1948, p. 206

- ^ a b c Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, p. 293

- ^ Mausfeld et al., 2002, p. 281

- ^ Whiting et al., 2006, pp. 720–721

- ^ Bauer, 2003, p. 5

- ^ Carranza and Arnold, 2003; Whiting et al., 2006

- ^ Miralles et al., 2009, p. 62

- ^ Miralles et al., 2009, p. 58

- ^ a b c d e Sazima et al., 2005, p. 186

- ^ Travassos, 1946, p. 8

- ^ Travassos, 1946, pp. 26–28; summarized in Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, table 1; nomenclature from Avila-Pires, 1995, pp. 9–10; Schleich et al., 1996, p. 372

- ^ Dunn, 1935, p. 536; Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, pp. 293–294; Miralles et al., 2009, p. 65

- ^ a b Travassos, 1946, pp. 26–28; summarized in Mausfeld and Vrcibradic, 2002, table 1

- ^ Greer et al., 2000, table 1

- ^ Travassos, 1946, p. 51

- ^ a b c Rocha et al., 2009, p. 454

- ^ Travassos, 1946, pp. 2–3

- ^ Travassos, 1946, pp. 26–28

- ^ a b c Silva et al., 2005, p. 63

- ^ a b Rocha et al., 2009, p. 457

- ^ Rocha et al., 2009, p. 455

- ^ Rocha et al., 2009, p. 456

- ^ a b c Sazima et al., 2005, p. 191

- ^ Sazima et al., 2009, p. 26

- ^ Gasparini et al., 2007, p. 30

- ^ Gasparini et al., 2007, p. 32

- ^ Ridley, 1888a, p. 46

- ^ a b Silva et al., 2005, table 1

- ^ a b Carleton and Olson, 1999, p. 48; Rocha et al., 2009, p. 450; Gasparini et al., 2007, p. 31; Silva et al., 2005, p. 62

- ^ a b c Rocha et al., 2009, p. 453

- ^ a b Silva et al., 2005, p. 62

- ^ Ridley, 1888b, p. 476

- ^ Rocha et al., 2009, p. 458

- ^ Branner, 1888, p. 861

- ^ Branner, 1888, pp. 866–867

- ^ Rocha et al., 2009, pp. 452, 457

- ^ Mausfeld et al., 2002, p. 289

- ^ Silva et al., 2005, p. 63; Gasparini et al., 2007, p. 32

- ^ a b Ramalho et al., 2009, p. 1026

- ^ a b Ramalho et al., 2009, p. 1027

External links[]

Literature cited[]

- Ananjeva, N. B.; Orlov, N. L.; Khalikov, R. G.; Darevsky, I. S.; and Barabanov, A.; 2006. The reptiles of northern Eurasia: taxonomic diversity, distribution, conservation status. Series faunistica 47. Pensoft Publishers, 245 pp. ISBN 978-954-642-269-9

- Avila-Pires, T. C. S.; 1995. Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299:1–706

- Bauer, A. M.; 2003. On the identity of Lacerta punctata Linnaeus 1758, the type species of the genus Euprepis Wagler 1830, and the generic assignment of Afro-Malagasy skinks. African Journal of Herpetology 52:1–7

- Boulenger, G. A.; 1887. Catalogue of the Lizards in the British Museum (Natural History). Second edition. Vol. III. Lacertidae, Gerrosauridae, Scincidae, Anelytropidae, Dibamidae, Chamaeleonidae. London: published by order of the Trustees of the British Museum, 575 pp.

- Branner, J. C.; 1888. Notes on the fauna of the islands of Fernando de Noronha (subscription required). American Naturalist 22(262):861–871

- Burt, C. E.; and Burt, M. D.; 1931. South American lizards in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 61:227–395

- Carleton, M. D.; and Olson, S. L.; 1999. Amerigo Vespucci and the rat of Fernando de Noronha: a new genus and species of Rodentia (Muridae, Sigmodontinae) from a volcanic island off Brazil's continental shelf. American Museum Novitates 3256:1–59

- Carranza, S.; and Arnold, N. E.; 2003. Investigating the origin of transoceanic distributions: mtDNA shows Mabuya lizards (Reptilia, Scincidae) crossed the Atlantic twice (subscription required). Systematics and Biodiversity 1(2):275–282

- DIELE-VIEGAS, L. M., T. FILADELFO, L. A. DE MENEZES, G. COELHO, C. LICARIAO, AND C. F. DUARTE ROCHA 2020. Trachylepis atlantica (Noronha Skink). Toe Loss. Herpetological Review. 51:133-134.

- Dunn, E. R.; 1935. Notes on American Mabuyas (subscription required). Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 87:533–557

- Finley, R. B., Jr.; 1945. Notes on lizards from Fernando Noronha (subscription required). Copeia 1945(3):162–164.

- Gasparini, J.L., Peloso, P.L. and Sazima, I. 2007. New opportunities and hazards brought by humans to the island habitat of the skink Euprepis atlanticus. Herpetological Bulletin 100:30–33

- Gray, J. E.; 1839. Catalogue of the slender-tongued saurians, with the description of many new genera and species. Annals and Magazine of Natural History (1)2:287–293

- Gray, J. E.; 1845. Catalogue of the specimens of lizards in the collection of the British Museum. London: published by order of the Trustees of the British Museum, 289 pp.

- Greer, A. E.; Arnold, C.; and Arnold, E. N.; 2000. The systematic significance of the number of presacral vertebrae in the scincid lizard genus Mabuya (subscription required). Amphibia-Reptilia 21:121–126

- Lyra, M. L. & M. Vences 2018. Preliminary assessment of mitochondrial variation in the insular endemic, biogeographically enigmatic Noronha skink, Trachylepis atlantica (Squamata: Scincidae). pp. Salamandra 54 (3): 229-232

- Mausfeld, P.; and Vrcibradic, D.; 2002. On the nomenclature of the skink (Mabuya) endemic to the western Atlantic archipelago of Fernando de Noronha, Brazil (subscription required). Journal of Herpetology 36(2):292–295

- Mausfeld, P.; Schmitz, A.; Böhme, W.; Misof, B.; Vrcibradic, D.; and Duarte, C. F.; 2002. Phylogenetic affinities of Mabuya atlantica Schmidt, 1945, endemic to the Atlantic Ocean archipelago of Fernando de Noronha (Brazil): Necessity of partitioning the genus Mabuya Fitzinger, 1826 (Scincidae: Lygosominae) (subscription required). Zoologischer Anzeiger 241:281–293

- Miralles, A.; Chaparro, J. C.; and Harvey, M. B.; 2009. Three rare and enigmatic South American skinks (first page only). Zootaxa 2012:47–68

- O'Shaughnessy, A. M. E.; 1874. Descriptions of new species of Scincidae in the collection of the British Museum. Annals and Magazine of Natural History (4)13:298–301

- Ramalho, A. C. O.; Silva, R. J. da; Schwartz, H. O.; Péres, A. K. (2009). "Helminths from an introduced species (Tupinambis merianae), and two endemic species (Trachylepis atlantica and Amphisbaena ridleyi) from Fernando de Noronha archipelago, Brazil". Journal of Parasitology. 95 (4): 1026–1028. doi:10.1645/GE-1689.1. JSTOR 27735698.

- Ridley, H. N.; 1888a. A visit to Fernando do Noronha. The Zoologist (3)12(134):41–49

- Ridley, H. N.; 1888b. Notes on the zoology of Fernando Noronha. Journal of the Linnean Society: Zoology 20:473–570

- Rocha, C. F. D.; Vrcibradic, D.; Menezes, V. A.; and Ariani, C. V.; 2009. Ecology and natural history of the easternmost native lizard species in South America, Trachylepis atlantica (Scincidae), from the Fernando de Noronha archipelago, Brazil (subscription required). Journal of Herpetology 43(3):450–459

- Sazima, Ivan; Sazima, Cristina; Sazima, Marlies (2005). "Little dragons prefer flowers to maidens: a lizard that laps nectar and pollinates trees". Biota Neotropica. 5 (1): 185–192. doi:10.1590/S1676-06032005000100018.

- Sazima, I.; Sazima, C.; and Sazima, M.; 2009. A catch-all leguminous tree: Erythrina velutina visited and pollinated by vertebrates at an oceanic island (subscription required). Australian Journal of Botany 57:26–30

- Schleich, H.-H.; Kästle, W.; and Kabisch, K.; 1996. Amphibians and reptiles of North Africa: biology, systematics, field guide. Koeltz Scientific Books, 630 pp. ISBN 978-3-87429-377-8

- Schmidt, K. P.; 1945. A new name for a Brazilian Mabuya. Copeia 1945(1):45

- Silva, J. M., Jr.; Péres, A. K., Jr.; and Sazima, I.; 2005. Euprepis atlanticus (Noronha Skink). Predation. Herpetological Review 36:62–63

- Travassos, H.; 1946. Estudo da variação de Mabuya punctata (Gray, 1839). Boletim do Museu Nacional (Zoologia) 60:1–56 (in Portuguese)

- Travassos, H.; 1948. Nota sobre a "Mabuya" da Ilha Fernando de Noronha (Squamata, Scincidae). Revista Brasileira de Biologia 8:201–208 (in Portuguese)

- Whiting, A. S.; Sites, J. W.; Pellegrino, K. C. M.; and Rodrigues, M. T.; 2006. Comparing alignment methods for inferring the history of the new world lizard genus Mabuya (Squamata: Scincidae) (subscription required). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 38:719–730

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Trachylepis

- Reptiles of Brazil

- Endemic fauna of Brazil

- Fernando de Noronha

- Reptiles described in 1945

- Taxa named by Karl Patterson Schmidt