North Sea Continental Shelf cases

| North Sea Continental Shelf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | International Court of Justice |

| Full case name | North Sea Continental Shelf (Federal Republic of Germany/Netherlands) |

| Decided | February 20, 1969 |

| Case opinions | |

| Declaration attached to Judgment: Muhammad Zafrulla Khan Declaration attached to Judgment: César Bengzon | |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | José Bustamante y Rivero (President) (Vice President) Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice Kōtarō Tanaka Philip Jessup Muhammad Zafrulla Khan Luis Padilla Nervo César Bengzon Manfred Lachs Mosler (ad hoc for Germany) Max Sørensen (ad hoc for The Netherlands) |

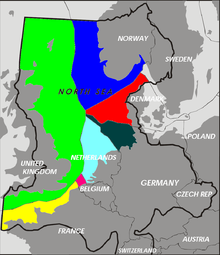

Germany v Denmark and the Netherlands [1969] ICJ 1 (also known as The North Sea Continental Shelf cases) were a series of disputes that came to the International Court of Justice in 1969. They involved agreements among Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands regarding the "delimitation" of areas—rich in oil and gas—of the continental shelf in the North Sea.

Facts[]

Germany's North Sea coast is concave, while the Netherlands' and Denmark's coasts are convex. If the delimitation had been determined by the equidistance rule ("drawing a line each point of which is equally distant from each shore"), Germany would have received a smaller portion of the resource-rich shelf relative to the two other states. Thus Germany argued that the length of the coastlines be used to determine the delimitation.[1] Germany wanted the ICJ to apportion the Continental Shelf to the proportion of the size of the state's adjacent land, which Germany found to be 'a just and equitable share', and not by the rule of equidistance.

Relevant is that Denmark and The Netherlands, having ratified the 1958 Geneva Continental Shelf Convention, whereas the Federal Republic of Germany did not, wished that Article 6, p. 2 (equidistance principle) were to be applied.

Article 6

- Where the same continental shelf is adjacent to the territories of two or more States whose coasts are opposite each other, the boundary of the continental shelf appertaining to such States shall be determined by agreement between them. In the absence of agreement, and unless another boundary line is justified by special circumstances, the boundary is the median line, every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured.

- Where the same continental shelf is adjacent to the territories of two adjacent States, the boundary of the continental shelf shall be determined by agreement between them. In the absence of agreement, and unless another boundary line is justified by special circumstances, the boundary shall be determined by application of the principle of equidistance from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured.

- In delimiting the boundaries of the continental shelf, any lines which are drawn in accordance with the principles set out in paragraphs 1 and 2 of this article should be defined with reference to charts and geographical features as they exist at a particular date, and reference should be made to fixed permanent identifiable points on the land.

Judgment[]

An important question the Court answered was if the equidistance principle was, at the date of the ruling, a customary international law binding on all States. The Court argued that it is indeed possible for Conventions, while only contractual in origin, to pass into the corpus of international law, and thus become binding for countries which have never become parties to the Convention. However, the Court notes that 'this result is not lightly to be regarded as having been attained' (para 71). For the aforegoing to happen, it would first be necessary that the provision should be of a fundamentally norm creating character, i.e. a general rule of law. In case, the obligation of the equidistance method came second, after the primary obligation to effect delimitation by agreement. The court decides this is an unusual preface for it to be a general rule of law. Furthermore, the Court took in notion that the scope and meaning relating to the equidistance as embodied in Article 6 remained unclear. In para 74, the Court argues that while the passage of any considerable period of time is not a requirement, it is an indispensable requirement that within the period in question State practice should have been both extensive and virtually uniform in the sense of the provision invoked.

Moreover, as stated in para 77, the practice must also, as a subjective element, stem from a notion of opinio juris sive necessitatis. In other words, the States concerned must feel they are conforming to what amounts to a legal obligation.

The Court ultimately urged the parties to "abat[e] the effects of an incidental special feature [Germany's concave coast] from which an unjustifiable difference of treatment could result." In subsequent negotiations, the states granted to Germany most of the additional shelf it sought.[2] The cases are viewed as an example of "equity praeter legem"—that is, equity "beyond the law"—when a judge supplements the law with equitable rules necessary to decide the case at hand.[3]

See also[]

Notes[]

- North Sea

- Continental shelves of Europe

- International Court of Justice cases

- 1969 in international relations

- 1969 in case law

- Denmark–Germany border

- Germany–Netherlands border

- 1969 in Denmark

- 1969 in Germany

- 1969 in the Netherlands

- International law