Novel in Scotland

The novel in Scotland includes all long prose fiction published in Scotland and by Scottish authors since the development of the literary format in the eighteenth century. The novel was soon a major element of Scottish literary and critical life. Tobias Smollett's picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle mean that he is often seen as Scotland's first novelist. Other Scots who contributed to the development of the novel in the eighteenth century include Henry Mackenzie and John Moore.

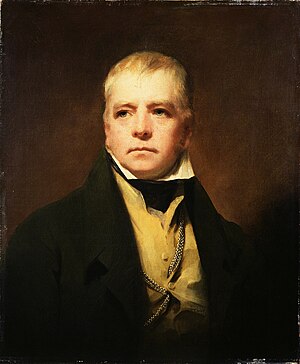

There was a tradition of moral and domestic fiction in the early nineteenth century that included the work of Elizabeth Hamilton, Mary Brunton and Christian Johnstone. The outstanding literary figure of the early nineteenth century was Walter Scott, whose Waverley is often called the first historical novel. He had a major worldwide influence. His success led to a publishing boom in Scotland. Major figures that benefited included James Hogg, John Galt, John Gibson Lockhart, John Wilson and Susan Ferrier. In the mid-nineteenth century major literary figures that contributed to the development of the novel included David Macbeth Moir, John Stuart Blackie, William Edmondstoune Aytoun and Margaret Oliphant. In the late nineteenth century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations, including Robert Louis Stevenson and Arthur Conan Doyle, whose Sherlock Holmes stories helped found the tradition of detective fiction. In the last two decades of the century the "kailyard school" (cabbage patch) depicted Scotland in a rural and nostalgic fashion, often seen as a "failure of nerve" in dealing with the rapid changes that had swept across Scotland in the industrial revolution. Figures associated with the movement include Ian Maclaren, S. R. Crockett and J. M. Barrie, best known for his creation of Peter Pan, which helped develop the genre of fantasy, as did the work of George MacDonald.

Among the most important novels of the early twentieth century was The House with the Green Shutters by George Douglas Brown, which broke with the Kailyard tradition. John Buchan played a major role in the creation of the modern thriller with The Thirty-Nine Steps and Greenmantle. The Scottish literary Renaissance attempted to introduce modernism into art and create of a distinctive national literature. It increasingly focused on the novel. Major figures included Neil Gunn, George Blake, A. J. Cronin, Eric Linklater and Lewis Grassic Gibbon. There were also a large number of female authors associated with the movement, who included Catherine Carswell, Willa Muir, Nan Shepherd and Naomi Mitchison. Many major Scottish post-war novelists, such as Robin Jenkins, Jessie Kesson, Muriel Spark, Alexander Trocchi and James Kennaway spent most of their lives outside Scotland, but often dealt with Scottish themes. Successful mass-market works included the action novels of Alistair MacLean and the historical fiction of Dorothy Dunnett. A younger generation of novelists that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s included Allan Massie, Shena Mackay and Alan Spence. Working class identity continued to be explored by Archie Hind, Alan Sharp, George Friel and William McIlvanney.

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, with figures including Alasdair Gray, James Kelman, Irvine Welsh, Alan Warner, Janice Galloway, A. L. Kennedy, Iain Banks, Candia McWilliam, Frank Kuppner and Andrew O'Hagan. In genre fiction Iain Banks, writing as Iain M. Banks, produced ground-breaking science fiction and Scottish crime fiction has been a major area of growth with the success of novelists including Frederic Lindsay, Quintin Jardine, Val McDermid, Denise Mina, Christopher Brookmyre, and particularly Ian Rankin and his Inspector Rebus novels.[1]

Eighteenth century[]

The novel in its modern form developed rapidly in the eighteenth century and was soon a major element of Scottish literary and critical life. There was a demand in Scotland for the newest novels including Robinson Crusoe (1719), Pamela (1740), Tom Jones (1749) and Evelina (1788). There were weekly reviews of novels in periodicals, the most important of which were The Monthly Review and The Critical Review. Lending libraries were established in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen. Private manor libraries were established in estate houses. The universities began to acquire novels and they became part of the curriculum.[2] By the 1770s about thirty novels were being printed in Britain and Ireland every year and there is plentiful evidence that they were being read, particularly by women and students in Scotland. Scotland and Scottish authors made a modest contribution to this early development. About forty full length prose books were printed in Scotland before 1800. One of the earliest was the anonymously authored Select Collection of Oriental Tales (1776).[3]

Tobias Smollett (1721–71) was a poet, essayist, satirist and playwright, but is best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748) and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751) for which he is often seen as Scotland's first novelist.[4] His most influential novel was his last, the epistolary novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771).[5] His work would be a major influence on later novelists such as Thackeray and Dickens.[3] Other eighteenth-century novelists included Henry Mackenzie (1745–1821), whose major work The Man of Feeling (1771) was a sentimental novel dealing with human emotions, influenced by Samuel Richardson and Lawrence Sterne and the thinking of philosopher David Hume. His later novels, The Man of the World (1773) and Julia de Roubigné (1777) were set in the wilds of America and in France respectively, with the character of the title of the latter being the first female protagonist throughout a Scottish novel.[6] Physician John Moore's novel Zeluco (1789) focused on an anti-hero, the Italian nobleman of the title, and was a major influence on the work of Byron.[7]

Nineteenth century[]

As elsewhere in the British Isles there was a tradition of moral and domestic fiction in the early nineteenth century. It did not flourish to the same extent in Scotland, but did produce a number of significant publications. These included Elizabeth Hamilton's (1756?–1816), Cottagers of Glenburnie (1808), Mary Brunton's (1778–1818) Discipline (1814) and Christian Johnstone's Clan-Albin (1815).[8]

The outstanding literary figure of the early nineteenth century was Walter Scott (1771–1832). Having begun as a ballad collector and poet, his first prose work, Waverley in 1814, often called the first historical novel, launched a highly successful career as a novelist.[9] His first nine novels dealt with Scottish history, particularly of the Highlands and Borders and included Rob Roy (1817) and The Heart of Midlothian (1818). Beginning with Ivanhoe (1820) he turned to English history and began the European vogue for his work. He was created a baronet by George IV in 1820, the first literary figure to receive the honour. His work helped to solidify the respectability of the novel as literature[10] and did more than any other figure to define and popularise Scottish cultural identity in the nineteenth century.[11] He is considered the first novelist writing in English to enjoy an international career in his own lifetime,[12] having a major influence on novelists in Italy, France, Russia and the US as well as Great Britain.[10]

Scott's success led to a publishing boom in Scotland that benefited his imitators and rivals. Scottish publishing increased threefold as a proportion of all publishing in Great Britain, reaching a peak of 15 per cent in 1822–25. Many novels were original serialised in periodicals, which included The Edinburgh Review, founded in 1802 and Blackwood's Magazine, founded in 1817, both of which were owned by Scott's publisher Blackwoods.[8] Together they had a major impact on the development of British literature in the era of Romanticism, helping to solidify the literary respectability of the novel.[13][14]

The major figures that benefited from this boom included James Hogg (1770–1835), whose best known work is The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824), which dealt with the themes of Presbyterian religion and Satanic possession, evoking the landscape of Edinburgh and its surrounding environment.[15] John Galt's (1779–1839) most famous work was Annals of the Parish (1821), given in the form of a diary kept by a rural minister over a fifty-year period and allowing Galt to make observations about the changes in Scottish society.[16] Walter Scott's son-in-law John Gibson Lockhart (1794–1854), is most noted for his Life of Adam Blair (1822) which focuses on the contest between desire and guilt.[16] The lawyer and critic John Wilson, as Christopher North, published novels including Lights and Shadows of Scottish Life (1822), The Trials of Margaret Lyndsay (1823) and The Foresters (1825), which investigate individual psychology.[17] The only major female novelist to emerge in the aftermath of Scott's success was Susan Ferrier (1782–1854), whose novels Marriage (1818), The Inheritance (1824) and Destiny (1831), continued the domestic tradition.[8]

In the mid-nineteenth century major literary figures that contributed to the development of the novel included David Macbeth Moir (1798–1851), John Stuart Blackie (1809–95) and William Edmondstoune Aytoun (1813–65).[16] Margaret Oliphant (1828–97) produced over a hundred novels, many of them historical or studies of manners set in Scotland and England,[18] including The Minister's Wife (1886) and Kirsteen (1890). Her series the Chronicles of Carlingford has been compared with the best work of Anthony Trollope.[19]

In the late nineteenth century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations. Robert Louis Stevenson's (1850–94) work included the urban Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), which explored the psychological consequences of modernity. Stevenson was also crucial to the further development of the historical novel with historical adventures in books like Kidnapped (1886) and Treasure Island (1893) and particularly The Master of Ballantrae (1888), which used historical backgrounds as a mechanism for exploring modern concerns through allegory.[18] Arthur Conan Doyle's (1859–1930) Sherlock Holmes stories produced the archetypal detective figure and helped found the tradition of detective fiction.[18]

In the last two decades of the century the "kailyard school" (cabbage patch) depicted Scotland in a rural and nostalgic fashion, often seen as a "failure of nerve" in dealing with the rapid changes that had swept across Scotland in the industrial revolution. Figures associated with the movement include Ian Maclaren (1850–1907), S. R. Crockett (1859–1914) and most famously J. M. Barrie (1860–1937), best known for his creation of Peter Pan, which helped develop the genre of fantasy.[18] Also important in the development of fantasy was the work of George MacDonald (1824–1905) whose produced children's novels, including The Princess and the Goblin (1872) and At the Back of the North Wind (1872), realistic novels of Scottish life, but also Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women (1858) and later Lilith: A Romance (1895), which would be an important influence on the work of both C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien.[18]

Early twentieth century[]

Among the most important novels of the early twentieth century was The House with the Green Shutters (1901) by George Douglas Brown (1869–1902), a realist work that broke with the Kailyard tradition to depict modern Scottish society, using Scots language and disregarding nostalgia.[18] Also important was the work of John Buchan (1875–1940), who played a major role in the creation of the modern thriller with The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915) and Greenmantle (1916). His prolific output included the historical novel Witchwood (1927), set in seventeenth-century Scotland, and the posthumously published Sick Heart River (1941), a study of physiological breakdown in the wilderness of Canada (of which Buchan was governor-general from 1936 until his death). His work was an important link between the tradition of Scot and Stevenson and the Scottish Renaissance.[20]

The Scottish literary Renaissance was an attempt to introduce modernism into art and to create a distinctive national literature. In its early stages the movement was mainly focused on poetry, but increasingly concentrated on the novel, particularly after the 1930s when its major figure Hugh MacDiarmid was living in isolation in Shetland and its leadership moved to novelist Neil Gunn (1891–1973). Gunn's novels, beginning with The Grey Coast (1926), and including Highland River (1937) and The Green Isle of the Great Deep (1943), were largely written in English and not the Scots preferred by MacDiarmid, focused on the Highlands of his birth and were notable for their narrative experimentation.[20] Other major figures associated with the movement include George Blake (1893–1961), A. J. Cronin (1896–1981), Eric Linklater (1899–1974) and Lewis Grassic Gibbon (1901–1935). There were also a large number of female authors associated with the movement, who demonstrated a growing feminine consciousness. They included Catherine Carswell (1879–1946), Willa Muir (1890–1970),[20] Nan Shepherd (1893–1981)[1] and most prolifically Naomi Mitchison (1897–1999).[20] All were born within a fifteen-year period and, although they cannot be described as members of a single school, they all pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues.[1] Physician A. J. Cronin is now often seen as sentimental, but his early work, particularly his first novel Hatter's Castle (1931) and his most successful The Citadel (1937) were a deliberate reaction against the Kailyard tradition, exposing the hardships and vicissitudes of the lives of ordinary people,[21] He was the most translated Scottish author in the twentieth century.[22] George Blake pioneered the exploration of the experiences of the working class in his major works such as The Shipbuilders (1935). Eric Linklater produced comedies of the absurd including Juan in America (1931) dealing with prohibition America, and a critique of modern war in Private Angelo (1946). Lewis Grassic Gibbon, the pseudonym of James Leslie Mitchell, produced one of the most important realisations of the ideas of the Scottish Renaissance in his trilogy A Scots Quair (Sunset Song, 1932, Cloud Howe, 1933 and Grey Granite, 1934), which mixed different Scots dialects with the narrative voice.[20] Other works that investigated the working class included James Barke's (1905–58), Major Operation (1936) and The Land of the Leal (1939) and J. F. Hendry's (1912–86) Fernie Brae (1947).[20]

Late twentieth century to the present[]

World War II had a greater impact on the novel than in poetry. It ended the careers of some novelists and delayed the start of others.[20] Many major Scottish post-war novelists, such as Robin Jenkins (1912–2005), Jessie Kesson (1916–94), Muriel Spark (1918–2006), Alexander Trocchi (1925–84) and James Kennaway (1928–68) spent much or most of their lives outside Scotland, but often dealt with Scottish themes.[1] Jenkins major novels such as The Cone Gatherers (1955), The Changeling (1958) and Fergus Lamont (1978) focused on working-class dilemmas in a world without spiritual consolation. Very different in tone, Spark produced novels that explored modern social life as in her only two overtly Scottish novels The Ballad of Peckham Rye (1960) and the Edinburgh-set The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961).[20] Successful mass-market works included the action novels of Alistair MacLean (1922–87), and the historical fiction of Dorothy Dunnett (b. 1923).[1] A younger generation of novelists that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s included Allan Massie (b. 1938), Shena Mackay (b. 1944) and Alan Spence (b. 1947).[1] Massie's work often deals with historical themes while aware of the limitations of historical objectivity, as in his Augustus (1986), Tiberius (1991) and The Ragged Lion (1994).[20] Working class identity continued to be a major theme in the post-war novel and can be seen in Archie Hind's (1928–2008) The Dear Green Place (1966), Alan Sharp's (1934–2013) A Green Tree in Gedde (1965), George Friel's (1910–75) Mr Alfred M.A. (1972) and William McIlvanney's (b. 1936) Docherty (1975).[20]

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher Philip Hobsbaum (1932–2005). Also important in the movement was Peter Kravitz, editor of Polygon Books.[1] These included Alasdair Gray (b. 1934), whose epic Lanark (1981) built on the working class novel to explore realistic and fantastic narratives. James Kelman’s (b. 1946) The Busconductor Hines (1984) and A Disaffection (1989) were among the first novels to fully utilise a working class Scots voice as the main narrator.[20] In the 1990s major, prize winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement included Gray's Poor Things (1992), which investigated the capitalist and imperial origins of Scotland in an inverted version of the Frankenstein myth,[20] Irvine Welsh's (b. 1958), Trainspotting (1993), which dealt with the drug addiction in contemporary Edinburgh, Alan Warner’s (b. 1964) Morvern Callar (1995), dealing with death and authorship and Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late (1994), a stream of consciousness novel dealing with a life of petty crime.[1] These works were linked by a reaction to Thatcherism, that was sometimes overtly political, and explored marginal areas of experience using vivid vernacular language (including expletives and Scots dialect).[1]

Other notable authors to gain prominence in this period included Janice Galloway (b. 1956) with work such as The Trick is to Keep Breathing (1989) and Foreign Parts (1994); A. L. Kennedy (b. 1965) with Looking for the Possible Dance (1993) and So I Am Glad (1995); Iain Banks (1954–2013) with The Crow Road (1992) and Complicity (1993); Candia McWilliam (b, 1955) with Debatable land (1994); Frank Kuppner (b. 1951) with Something Very Like Murder (1994); and Andrew O'Hagan (b. 1968) with Our Fathers (1999).[20] In genre fiction Iain Banks, writing as Iain M. Banks, produced ground-breaking science fiction.[20] Scottish crime fiction, known as Tartan Noir,[23] has been a major area of growth with the success of novelists including Frederic Lindsay (1933–2013), Quintin Jardine (b. 1945), Val McDermid (b. 1955), Denise Mina (b. 1966), Christopher Brookmyre (b. 1968), and particularly the success of Edinburgh's Ian Rankin (b. 1960) and his Inspector Rebus novels.[1]

Notes[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Scottish 'Renaissance' and beyond", Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile, archived from the original on 5 November 2011

- ^ P. G. Bator, "The entrance of the novel into the Scottish universities", in R. Crawford, ed., The Scottish Invention of English Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), ISBN 0521590388, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X, p. 313.

- ^ J. C. Beasley, Tobias Smollett: Novelist (University of Georgia Press, 1998), ISBN 0820319716, p. 1.

- ^ R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X, p. 316.

- ^ R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X, pp. 321–3.

- ^ R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X, p. 392.

- ^ a b c I. Duncan, "Scott and the historical novel: a Scottish rise of the novel", in G. Carruthers and L. McIlvanney, eds, The Cambridge Companion to Scottish Literature (Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 2012), ISBN 0521189365, p. 105.

- ^ K. S. Whetter, Understanding Genre and Medieval Romance (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 0-7546-6142-3, p. 28.

- ^ a b G. L. Barnett, ed., Nineteenth-Century British Novelists on the Novel (Ardent Media, 1971), p. 29.

- ^ N. Davidson, The Origins of Scottish Nationhood (Pluto Press, 2008), ISBN 0-7453-1608-5, p. 136.

- ^ R. H. Hutton, Sir Walter Scott (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 1108034675, p. 1.

- ^ A. Jarrels, "'Associations respect[ing] the past': Enlightenment and Romantic historicism", in J. P. Klancher, A Concise Companion to the Romantic Age (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), ISBN 0631233555, p. 60.

- ^ A. Benchimol, ed., Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), ISBN 0754664465, p. 210.

- ^ A. Maunder, FOF Companion to the British Short Story (Infobase Publishing, 2007), ISBN 0816074968, p. 374.

- ^ a b c I. Campbell, "Culture: Enlightenment (1660–1843): the novel", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 138–40.

- ^ G. Kelly, English Fiction of the Romantic Period, 1789–1830 (London: Longman, 1989), ISBN 0582492602, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d e f C. Craig, "Culture: age of industry (1843–1914): literature", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 149–51.

- ^ A. C. Cheyne, "Culture: Age of Industry (1843–1914), general", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 143–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n C. Craig, "Culture: modern times (1914–): the novel", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 157–9.

- ^ R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X, p. 587.

- ^ P. Barnaby and T. Hubbard, "The international reception and impact of Scottish literature of the period since 1918", in I. Brown, ed., The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Modern transformations: new identities (from 1918) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748624821, p. 32.

- ^ P. Clandfied, "Putting the 'black' into 'tartan noir'" in Julie H. Kim, ed., Race and Religion in the Postcolonial British Detective Story: Ten Essays (McFarland, 2005), ISBN 0786421754, p. 221.

- Scottish literature

- History of literature in Scotland

- Scottish novels