Nymphaea

| Nymphaea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nymphaea 'Peach Glow' | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Order: | Nymphaeales |

| Family: | Nymphaeaceae |

| Genus: | Nymphaea L. |

| Species | |

|

About 36 species, see text[1] | |

Nymphaea /nɪmˈfiːə/ is a genus of hardy and tender aquatic plants in the family Nymphaeaceae. The genus has a cosmopolitan distribution. Many species are cultivated as ornamental plants, and many cultivars have been bred. Some taxa occur as introduced species where they are not native,[2] and some are weeds.[3] Plants of the genus are known commonly as water lilies,[2][4] or waterlilies in the United Kingdom. The genus name is from the Greek νυμφαία, nymphaia and the Latin nymphaea, which mean "water lily" and were inspired by the nymphs of Greek and Latin mythology.[2]

Description[]

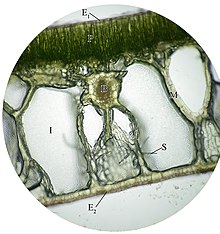

- E1: upper epiderm

- E2: lower epiderm

- P: palisade mesophyll

- M: spongy mesophyll

- B: vascular bundle

- I: intercellular gap

- S: sclerenchyma

Water lilies are aquatic rhizomatous herbaceous perennials, sometimes with stolons, as well. The stem is angular and erect. The leaves grow from the rhizome on long petioles(stalk that attaches the leaf blade to the stem). Floating round leaves of waterlily grow up to 12 inches across. The disc shaped leaves are notched and split to the stem in a V-shape at the centre, and are often purple underneath. Most of them float on the surface of the water. The blades have smooth or spine-toothed edges, and they can be rounded or pointed. The flowers rise out of the water or float on the surface, opening during the day or at night.[2] Many species of Nymphaea display protogynous flowering. The temporal separation of these female and male phases is physically reinforced by flower opening and closing, so the first flower opening displays female pistil and then closes at the end of the female phase, and reopens with male stamens.[5] Each has at least eight petals in shades of white, pink, blue, or yellow. Many stamens are at the center.[2] Water lily flowers are entomophilous, meaning they are pollinated by insects, often beetles.[2] The fruit is berry-like and borne on a curving or coiling peduncle.[2] Plant reproduce by root tubers and seeds.

Cultivation[]

Water lilies are not only decorative, but also provide useful shade which helps reduce the growth of algae in ponds and lakes.[6] Many of the water lilies familiar in water gardening are hybrids and cultivars. These cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:

- 'Escarboucle'[7] (orange-red)

- 'Gladstoniana'[8] (double white flowers with prominent yellow stamens)

- 'Gonnère'[9] (double white scented flowers)

- 'James Brydon;'[10] (cupped rose-red flowers)

- 'Marliacea Chromatella'[11] (pale yellow flowers)

- 'Pygmaea Helvola'[12] (miniature, with cupped fragrant yellow flowers)

Other uses[]

All water lilies are poisonous and contain an alkaloid called nupharin in almost all of their parts, with the exception of the seeds and in some species the tubers. The European species contain large amounts of nupharin, and are considered inedible. The amount of nupharin in the leaves and stalks appears to vary seasonally in European species. Nonetheless there is a Polish poem by Juliusz Słowacki in which the rhizomes are eaten. In some species the rhizomes and tubers are eaten after boiling has neutralised the nupharin. The Ancient Egyptians ate them boiled. In India it has mostly been eaten as a famine food or as a medicinal (both cooked), but in one area the dried rhizomes were pounded into a sort of bread, and the tubers are often eaten in the floodplains. In Vietnam rhizomes were eaten roasted. In Sri Lanka it was formerly eaten as a type of medicine and its price was too high to serve as a normal meal, but in the 1940s or earlier some villagers began to grow water lilies in the paddy fields left uncultivated during the monsoon season (Yala season), and the price dropped. The tubers are called manel here and eaten boiled and in curries. The tubers of a number of Australian, Asian and African species are completely edible, during the dry season some consist almost entirely of starch. The tubers of all occurring species were eaten in West Africa and Madagascar (where they are called tantamon for blue and laze-laze for white), usually boiled or roasted. In West Africa, usage varied between cultures, in the Upper Guinea the rhizomes were only considered famine foods -here the tubers were either roasted in ashes, or dried and ground into a flour. The Buduma people ate the seeds and rhizomes. Some tribes ate the rhizomes raw. The tubers of Nymphaea gigantea of Australia were roasted by certain tribes, these turn the colour blue when boiled, the tubers of other species were also roasted elsewhere on that continent. In China the tubers were eaten cooked. The plants were also said to be eaten in the Philippines. In the 1950s there were no records of leaves or flowers being eaten.[13] In a North American species, the boiled young leaves and unopened flower buds are said to be edible. The seeds, high in starch, protein, and oil, may be popped, parched, or ground into flour. Potato-like tubers can be collected from the species N. tuberosa.[14] Water lilies were said to have been a major food source for a certain tribe of indigenous Australians in 1930, with the flowers and stems eaten raw, while the "roots and seedpods" were cooked either on an open fire or in a ground oven.[15]

Taxonomy[]

This is one of several genera of plants known commonly as lotuses. It is not related to the legume genus Lotus or the East Asian and South Asian lotuses of genus Nelumbo. It is closely related to Nuphar lotuses, however. In Nymphaea, the petals are much larger than the sepals, whereas in Nuphar, the petals are much smaller. The process of fruit maturation also differs, with Nymphaea fruit sinking below the water level immediately after the flower closes, and Nuphar fruit remaining above the surface.

Subdivisions of genus Nymphaea:[16]

- Subgenus:

- Anecphya

- Brachyceras

- Hydrocallis

- Lotos

- Nymphaea:

- section Chamaenymphaea

- section Nymphaea

- section Xanthantha

- Nymphaea alba – white water lily (type species)

- – Amazon water lily

- – dotleaf water lily

- Nymphaea caerulea – blue Egyptian lotus

- Nymphaea candida

- Nymphaea capensis – Cape blue waterlily

- Nymphaea colorata

- – roundleaf water lily

- Nymphaea elegans – tropical royalblue water lily

- Nymphaea gigantea – giant water lily

- – sleeping beauty water lily

- – James' water lily

- Nymphaea leibergii – Leiberg's water lily

- Nymphaea lotus – Egyptian white water lily

- Nymphaea lotus f. thermalis

- Nymphaea macrosperma

- Nymphaea mexicana – yellow water lily

- - called as Miami Rose

- Nymphaea micrantha

- Nymphaea nouchali – blue lotus

- Nymphaea odorata – fragrant water lily

- Nymphaea pubescens – hairy water lily

- – India red water lily

- Nymphaea tetragona – pygmy water lily

- Nymphaea thermarum

- Nymphaea violacea

Cultural significance[]

The Ancient Egyptians used the water lilies of the Nile as cultural symbols.[17] Since 1580 it has become popular in the English language to apply the Latin word lotus, originally used to designate a tree, to the water lilies growing in Egypt, and much later the word was used to translate words in Indian texts.[18] The lotus motif is a frequent feature of temple column architecture. In Egypt, the lotus, rising from the bottom mud to unfold its petals to the sun, suggested the glory of the sun's own emergence from the primaeval slime. It was a metaphor of creation. It was a symbol of the fertility gods and goddesses as well as a symbol of the upper Nile as the giver of life.[17]

The flowers of the blue Egyptian water lily (N. caerulea) open in the morning and close at dusk, while those of the white water lily (N. lotus) open at night and close in the morning. Egyptians found this symbolic of the separation of deities and of death and the afterlife. Remains of both flowers have been found in the burial tomb of Ramesses II.

A Roman belief existed that drinking a liquid of crushed Nymphaea in vinegar for 10 consecutive days turned a boy into a eunuch.

A Syrian terra-cotta plaque from the 14th-13th centuries BC shows the goddess Asherah holding two lotus blossoms. An ivory panel from the 9th-8th centuries BC shows the god Horus seated on a lotus blossom, flanked by two cherubs.[19]

The French Impressionist painter Claude Monet is known for his many paintings of water lilies in the pond in his garden at Giverny.[20]

N. nouchali is the national flower of Bangladesh[21] and Sri Lanka.[22]

Water lilies are also used as ritual narcotics. This topic "was the subject of a lecture by William Emboden given at Nash Hall of the Harvard Botanical Museum on the morning of April 6, 1979".[23]

Examples[]

Nymphaea 'Attraction'

Nymphaea laydekeri purpurata

Nymphaea candida

Nymphaea × daubenyana

See also[]

- Albert de Lestang, propagator and seed collector

- List of plants known as lily

References[]

- ^ Nymphaea. The Plant List.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Nymphaea. Flora of North America.

- ^ Nymphaea. The Jepson eFlora 2013.

- ^ Nymphaea. Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

- ^ Povilus, R. A.; Losada, J. M.; Friedman, W. E. (2015). "Floral biology and ovule and seed ontogeny of Nymphaea thermarum, a water lily at the brink of extinction with potential as a model system for basal angiosperms". Annals of Botany. 115 (2): 211–226. doi:10.1093/aob/mcu235. PMC 4551091. PMID 25497514.

- ^ RHS A-Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. 2008. p. 1136. ISBN 978-1405332965.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector - Nymphaea 'Escarboucle'". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector - Nymphaea 'Gladstoniana'". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector - Nymphaea 'Gonnere'". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector - Nymphaea 'James Brydon'". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector - Nymphaea 'Marliacea Chromatella'". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector - Nymphaea 'Pygmaea Helvola'". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ FR Irvine, RS Trickett - Water lilies as Food - Kew Bulletin, 1953

- ^ Peterson, L. A. (1977). A Field Guide to the Wild Edible Plants of Eastern and Central North America. New York, New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 22.

- ^ McConnel, U. H. 1930. ‘The Wik-Munkan Tribe of Cape York Peninsula’. Oceania 1: 97–108

- ^ "USDA GRIN Taxonomy. Nymphaea L."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tresidder, Jack (1997). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Symbols. London: Duncan Baird Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 1-85986-059-1.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "The Origin and Meaning of the word 'Lotus'". Etymology Online. Douglas Harper. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Dever, W. G. Did God have a Wife? Archeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2008. pp 221, 279.

- ^ "Water Lilies: Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. December 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Bangladesh Constitution. Part I, The Republic, 4(3)".

- ^ Jayasuriya, M. Our national flower may soon be a thing of the past. The Sunday Times April 17, 2011.

- ^ "The Ethnopharmacology Society Newsletter". 2 (4). Spring 1979.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nymphaea. |

Further reading[]

- Slocum, P. D. Waterlilies and Lotuses. Timber Press. 2005. ISBN 0-88192-684-1 (restricted online version at Google Books)

- Nymphaea

- Nymphaeales genera

- Freshwater plants

- Medicinal plants