Oakwood, Los Angeles

Oakwood | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Los Angeles | |

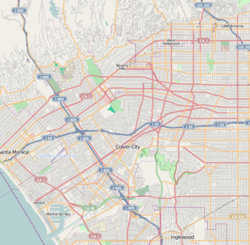

Oakwood Location within Los Angeles | |

| Coordinates: = = 33°59′50″N 118°27′50″W / 33.99722°N 118.46389°WCoordinates: 33°59′50″N 118°27′50″W / 33.99722°N 118.46389°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Time zone | Pacific |

| Zip Code | 90291 |

| Area code(s) | 310, 424 |

Oakwood is a residential neighborhood that abuts the east side of Abbot Kinney Boulevard. [1] It is within the larger neighborhood of Venice on the westside of Los Angeles. The area is noted as an "important example of African-American life in Southern California during the early 20th century".[2] The neighborhood has alternately been referred to as "Ghost Town",[3] "Dogtown" [4] and the "Oakwood Pentagon".[5] It contains one Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument.

Geography[]

Oakwood is bounded by Dewey Street to the northwest, Lincoln Boulevard to the northeast, California Avenue to the southeast, Electric Avenue to the southwest, and Hampton Drive to the west.[2]

History[]

It is uncertain if racially-restrictive housing covenants were in place in Venice at the beginning of the 20th Century (they were in place in Santa Monica, which is located to the north). However, de facto segregation in hiring practices and real estate sales led to the development of Oakwood as a predominantly African-American neighborhood. Between 1910 and 1920, the population of African-Americans in Venice tripled as blacks arrived to work as manual laborers, service workers, and servants to wealthy white residents.[2]

Employees hired by Abbot Kinney were the first black residents of Oakwood; among them were the two cousins Arthur Reese and Irvin Tabor. Reese was an artist and sculptor, best known for decorating parade floats simulating Mardi Gras; Kinney hired him as the town decorator. Tabor forged a close bond with his employer, working as Kinney's chauffeur.[2] When Kinney died in 1920, he had willed his house to Tabor. Two years later, to escape from racism[2] in Venice, Tabor relocated two of the structures from Kinney's St. Marks Island to their present-day location in Oakwood.[6] Today in Oakwood both the Reese and Tabor residences remain.[2]

A second phase of migration from the Southern states occurred during World War II. The population of blacks in Oakwood tripled again between 1940 and 1950. They had come to meet the need for defense workers at the nearby manufacturing facilities such as Hughes Aircraft in Culver City and McDonnell Douglas in Santa Monica.[2]

By the end of the 20th century Oakwood had gentrified. Homes had sold for more than US$1 million and longtime residents were being displaced. [7] Others left by choice, to cash in on the soaring property values. The head of the Venice Stakeholders Association said "A large population of black Americans who may have owned from Abbot Kinney’s time voluntarily took their equity and left".[3]

In 2007 the Latino student group Xinachtli (a subset of MEChA) from Venice High School referred to Oakwood as being "unique" with a "ethnically diverse population" and as having "one of the last ethnically and economically diverse beach communities in the state of California".[8]

In 2012, the Los Angeles Times reported that the breakneck pace of change along on Rose Avenue — at the northern end of Oakwood — suggested that the bohemian days of this once-down-and-out "countercultural beach neighborhood" were numbered. The wine shops, cafes, restaurants would eventually lead to the other streets of Venice being transformed into upmarket areas. "The tipping point has been tipped" said former Los Angeles City Councilwoman Ruth Galanter.[9]

The Irvin Tabor Residence was designated as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 2017. [6]

In 2018, American billionaire Jay Penske revealed his plans to convert a former African-American church building in Oakwood into an 11,000-square-foot mansion.[10] Community residents tried to prevent this plan by having the building—the First Baptist Church of Venice—"designated a historic landmark".[11] Contrary to the wishes of those fighting against Penske's plan, the Venice Neighborhood Council voiced approval for the project. [12] On December 18, 2018, the Los Angeles City Council voted to not declare the property a historic cultural monument, citing "removal of all stained glass...bronze hardware...and...the pews and most of the historic fabric [from] the interior of the church".[13]

Demographics[]

In 1950, African-Americans made up 12.6% of the Oakwood population. By 1970, that number had grown to 44.9%. By 1980, that number had dropped to 29.9%. By 2000, the African-American population was down to 16%,[14] Latinos made up 48% of Oakwood and whites made up 33%. By 2009, whites had become the largest racial-ethnic group in Oakwood, with Latinos at 33% and African-Americans at 16%. [15]

According to the Los Angeles Times, in 2000, about half the people living in the two census tracts along Rose Avenue were Latino, and a third white. But by 2010, the proportions had flipped, with whites making up nearly half of all residents in those tracts. [9]

Education[]

- Broadway Elementary School - 1015 Lincoln Boulevard [16]

Parks and recreation[]

- Oakwood Recreation Center - 767 California Avenue [17]

Landmarks[]

- Irvin Tabor Family Residences - Los Angeles Cultural Historic Monument #1149, located 605-607 East Westminster Avenue. [6]

References[]

- ^ Abcarian, Robin (July 19, 2017). "How 'progress' is wrecking Los Angeles neighborhoods". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "SurveyLA: Venice Community Plan Area" (PDF). Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ a b Carroll, Rory (December 1, 2016). "LA's black enclave buffeted by police pressure and tech-driven gentrification". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Divinity, Jeremy (July 6, 2020). "A Tale of Two Venices: Before There Was Dogtown, There Was Oakwood". KnockLA.com. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "VENICE LOCAL COASTAL PROGRAM COMMUNITY ISSUES ASSESSMENT" (PDF). LACity.org. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "Irvin Tabor Family Residences". Los Angeles Conservancy. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (November 6, 2003). "Gangster's Paradise Lost". Archived from the original on 2007-07-04.

- ^ "The Seed that Germinates (Xinachtli)". Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Stevens, Matt (December 11, 2012). "Venice's new bloom". Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Billionaire's Plan To Convert Venice Church Into Mega Mansion Under Fire". CBS News. June 20, 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Schneider, Gabe. "A Faction in Venice Is Trying to Stop a Former Black Church From Becoming a Mansion" (August 14, 2018). Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Swan, Jennifer. "The fight over the First Baptist Church of Venice". Curbed.com. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "RECOMMENDATION REPORT" (PDF). LACity.org. December 18, 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Deener, Andrew (June 2012). Venice A Contested Bohemia in Los Angeles. University of Chicago Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780226140025.

- ^ Deener, Andrew (June 2012). Venice A Contested Bohemia in Los Angeles. University of Chicago Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780226140025.

- ^ Maher, Adrian (October 6, 1994). "WESTSIDE / COVER STORY : Frowns Turned Upside Down". Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Oakwood Recreation Center". LAParks.org. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Neighborhoods in Los Angeles