Ofuda

In Japanese religion, an ofuda (お札 or 御札, honorific form of fuda, "slip (of paper), card, plate") is a talisman made out of various materials such as paper, wood, cloth or metal. Ofuda are commonly found in both Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples and are considered to be imbued with the power of the deities (kami) or Buddhist figures revered therein. Such amulets are also called gofu (護符).

A specific type of ofuda is a talisman issued by a Shinto shrine on which is written the name of the shrine or its enshrined kami and stamped with the shrine's seal. Such ofuda, also called shinsatsu (神札), go-shinsatsu (御神札) or shinpu (神符), are often placed on household Shinto altars (kamidana) and revered both as a symbol of the shrine and its deity (or deities) - indeed containing the kami's essence or power by virtue of its consecration - and a medium through which the kami in question can be accessed by the worshiper. In this regard they are somewhat similar to (but not the same as) goshintai, physical objects which serve as repositories for kami in Shinto shrines.

Other kinds of ofuda are intended for a specific purpose (such as protection against calamity or misfortune, safety within the home, or finding love) and may be kept on one's person or placed on other areas of the home (such as gates, doorways, kitchens, ceilings). Paper ofuda may also be referred to as kamifuda (紙札), while those made of wood may be called kifuda (木札). Omamori, another kind of Japanese amulet, originated and may be considered as a smaller, portable version of ofuda.

History[]

The practice of creating gofu originated from Onmyōdō - which adopted elements of Daoism - and Buddhism. Indeed, such ofuda and omamori were heavily influenced by the Daoist lingfu. Later, similar talismans also came to be produced at Shinto shrines.[1][2][3][4][5] The three shrines of Kumano in Wakayama Prefecture were particularly famous for their paper talisman, the Kumano Goōfu (熊野牛王符, 'Kumano Ox King Talisman'), also known as the Goōhōin (牛王宝印), which were stamped on one side with intricate designs of stylized crows.[6][7][8] During the medieval period, these and similar gofu produced by other shrines were often employed in oath taking and contract drafting, with the terms of the oath or agreement being written on the blank side of the sheet.[9][10][11][12]

The shinsatsu currently found in most Shinto shrines meanwhile are modeled after the talisman issued by the Grand Shrines of Ise (Ise Jingū) called Jingū Taima (神宮大麻). Jingū Taima were originally purification wands (祓串, haraegushi) that wandering preachers associated with the shrines of Ise (御師, oshi or onshi) handed out to devotees across the country as a sign and guarantee that prayers were conducted on their behalf. These wands, called Oharai Taima (御祓大麻), were contained either in packets of folded paper - in which case they are called kenharai (剣祓) (also kenbarai),[13] due to the packet's shape resembling a sword blade (剣, ken) - or in boxes called oharaibako (御祓箱). The widespread distribution of Oharai Taima first began in the Muromachi period and reached its peak in the Edo period: a document dating from 1777 (An'ei 6) indicates that eighty-nine to ninety percent of all households in the country at the time owned an Ise talisman.[13][14][15][16]

In 1871, an imperial decree abolished the oshi and allotted the production and distribution of the amulets, now renamed Jingū Taima, to the shrine's administrative offices.[14] It was around this time that the talisman's most widely known form - a wooden tablet containing a sliver of cedar wood known as gyoshin (御真, "sacred core")[13][17] wrapped in paper on which is printed the shrine's name (天照皇大神宮, Tenshō Kōtai Jingū) and stamped with the seals of the shrine (皇大神宮御璽, Kōtai Jingū Gyoji) and its high priest (大神宮司之印, Daijingūji no In) - developed. In 1900, a new department, the Kanbesho (神部署, "Department of Priests"), took over production and distribution duties. The distribution of Jingū Taima was eventually delegated to the National Association of Shinto Priests (全国神職会, Zenkoku Shinshokukai) in 1927 and finally to its successor, the Association of Shinto Shrines, after World War II.[14] The Association nowadays continues to disseminate Jingū Taima to affiliated shrines throughout Japan, where they are made available alongside the shrines' own amulets.

Varieties and usage[]

Ofuda come in a variety of forms. Some are slips or sheets of paper, others like the Jingū Taima are thin rectangular plaques (角祓, kakubarai/kakuharai) enclosed in an envelope-like casing (which may further be covered in translucent wrapping paper), while still others are wooden tablets (kifuda) which may be smaller or larger than regular shinsatsu. Some shrines distribute kenharai, which consists of a sliver of wood placed inside a fold of paper. As noted above, the Oharai Taima issued by the shrines of Ise before the Meiji period were usually in the form of kenharai; while the kakuharai variety is currently more widespread, Jingū Taima of the kenharai type are still distributed in Ise Shrine.[18]

Ofuda and omamori are available year round in many shrines and temples, especially in larger ones with a permanent staff. As these items are sacred, they are technically not 'bought' but rather 'received' (授かる, sazukaru or 受ける, ukeru), with the money paid in exchange for them being considered to be a donation or offering (初穂料, hatsuhoryō, literally 'first fruit fee').[19][20] One may also receive a wooden talisman called a kitōfuda (祈祷札) after having formal prayers or rituals (祈祷, kitō) performed on one's behalf in these places of worship.

Shinsatsu such as Jingū Taima are enshrined in a household altar (kamidana) or a special stand (ofudatate); in the absence of one, they may be placed upright in a clean and tidy space above eye level or attached to a wall. Shinsatsu and the kamidana that house them are set up facing east (where the sun rises), south (the principal direction of sunshine), or southeast.[21][22][23][24]

The Association of Shinto Shrines recommends that a household own at least three kinds of shinsatsu:

- Jingū Taima

- The ofuda of the tutelary deity of one's place of residence (ujigami)

- The ofuda of a shrine one is personally devoted to sūkei jinja (崇敬神社)

In a 'three-door' style (三社造, sansha-zukuri) altar, the Jingū Taima is placed in the middle, with the ofuda of one's local ujigami on its left (observer's right) and the ofuda of one's favourite shrine on its right (observer's left). Alternatively, in a 'one-door' style (一社造, issha-zukuri) kamidana, the three talismans are laid on top of one another, with the Jingū Taima on the front. One may own more shinsatsu; these are placed on either side of or behind the aforementioned three.[21][22][25][26][27] Regular (preferably daily) worship before the shinsatsu or kamidana and offerings of rice, salt, water, and/or sake to the kami (with additional foodstuffs being offered on special occasions) are recommended.[22][28] The manner of worship is similar to those performed in shrines: two bows, two claps, and a final bow, though a prayer (norito) - also preceded by two bows - may be recited before this.[29][30]

Other ofuda are placed in other parts of the house. For instance, ofuda of patron deities of the hearth - Sanbō-Kōjin in Buddhism, Kamado-Mihashira-no-Kami (the 'Three Deities of the Hearth': Kagutsuchi, Okitsuhiko and Okitsuhime) in Shinto[31][32] - are placed in the kitchen. In toilets, a talisman of the Buddhist wrathful deity Ucchuṣma (Ususama Myōō), who is believed to purify the unclean, may be installed.[33] Protective gofu such as Tsuno Daishi (角大師, "Horned Great Master"), a depiction of the Tendai monk Ryōgen in the form of a yaksha or an oni[34][35]) are placed on doorways or entrances.

Japanese spirituality lays great importance on purity and pristineness (tokowaka (常若, lit. "eternal youth")), especially of things related to the divine. It is for this reason that periodic (usually annual) replacement of ofuda and omamori are encouraged. It is customary to obtain new ofuda before the end of the year at the earliest or during the New Year season, though (as with omamori) one may purchase one at other times of the year as well. While ideally, old ofuda and omamori are to be returned to the shrine or temple where they were obtained as a form of thanksgiving, most Shinto shrines in practice accept talismans from other shrines.[23][36][37][38][39] (Buddhist ofuda are however not accepted in many shrines and vice versa.) Old ofuda and omamori are burned in a ceremony known either as Sagichō (左義長) or Dondoyaki (どんど焼き, also Dontoyaki or Tondoyaki) held during the Little New Year (January 14th or 15th), the end of the Japanese New Year season.[20][40][41]

Gallery[]

Goōfu from Kumano Hayatama Taisha

Kajikimen (鹿食免, "permit to eat deer"), a talisman issued by Suwa Shrine in Nagano Prefecture. At a time when meat eating was mostly frowned upon due to Buddhist influence, these were held to allow the bearer to eat venison and other meat without incurring impurity or negative karma.

An ofuda of the tutelary deities of the hearth (kamadogami), for use in kitchens (from Nishino Shrine in Sapporo)

Nichiren-shū talisman against disease, from a ritual manual

Part of a series of seventy-two talismans (reifu (霊符), from Chinese lingfu) known as Taijō Shinsen Chintaku Reifu (太上神仙鎮宅霊符, "Talismans of the Most High Gods and Immortals for Home Protection") or simply as Chintaku Reifu (鎮宅霊符, "Talismans for Home Protection"). Originally of Daoist origin, these were introduced to Japan during the Middle Ages.[42][43]

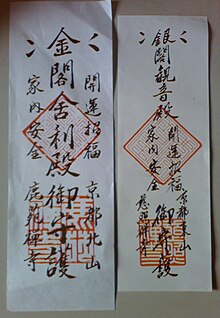

Jingū Taima and other shinsatsu

Ofuda posted beside a doorway

A sakasafuda (逆札, reverse fuda), a handmade talisman against theft displayed upside-down. This ofuda is inscribed with the date the legendary outlaw Ishikawa Goemon supposedly died: 'the 25th day of the 12th month' (十二月廿五日).[a][45] Other dates are written in other areas, such as 'the 12th day of the 12th month' (十二月十二日), which is claimed to be Goemon's birthdate.[44]

Different types of omamori and ofuda at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura

Place for returning old talismans (Hokoji Shrine, Takatō, Ina City, Nagano Prefecture)

A 'ship shrine' (艦内神社, kannai jinja) inside battleship Mikasa (currently in Mikasa Park in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture). Beside the altar is a wooden ofuda (kifuda) from Tōgō Shrine (dedicated to the deified naval leader Tōgō Heihachirō, who used Mikasa as his flagship) in Harajuku, Tokyo.

See also[]

- Omamori

- Senjafuda

- Fulu (Chinese paper charm or spell)

- Thai Buddha amulet

- Holy card

- Himmelsbrief

- Murti

Notes[]

- ^ The diary of contemporary aristocrat Yamashina Tokitsune seemingly indicates that the historical Goemon was executed on the 24th day of the 8th month (October 8th in the Gregorian calendar).[44]

References[]

- ^ Okada, Yoshiyuki. "Shinsatsu, Mamorifuda". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Wen, Benebell (2016). The Tao of Craft: Fu Talismans and Casting Sigils in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition. North Atlantic Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-1623170677.

- ^ Hida, Hirofumi (火田博文) (2017). 日本人が知らない神社の秘密 (Nihonjin ga shiranai jinja no himitsu). Saizusha. p. 22.

- ^ Mitsuhashi, Takeshi (三橋健) (2007). 神社の由来がわかる小事典 (Jinja no yurai ga wakaru kojiten). PHP Kenkyūsho. p. 115.

- ^ Chijiwa, Itaru (千々和到) (2010). 日本の護符文化 (Nihon no gofu bunka). Kōbundō. pp. 33–34.

- ^ "熊野牛王神符 (Kumano Goō Shinpu)". Kumano Hongū Taisha Official Website (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Kaminishi, Ikumi (2006). Explaining Pictures: Buddhist Propaganda And Etoki Storytelling in Japan. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 138–139.

- ^ Davis, Kat (2019). Japan's Kumano Kodo Pilgrimage: The UNESCO World Heritage trek. Cicerone Press Limited.

- ^ Hardacre, Helen (2017). Shinto: A History. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Shimazu, Norifumi. "Kishōmon". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Oyler, Elizabeth (2006). Swords, Oaths, And Prophetic Visions: Authoring Warrior Rule in Medieval Japan. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 69–70.

- ^ Grapard, Allan G. (2016). Mountain Mandalas: Shugendo in Kyushu. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 171–172.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Breen, John (2010). "Resurrecting the Sacred Land of Japan: The State of Shinto in the Twenty-First Century" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. 37 (2): 295–315.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Nakanishi, Masayuki. "Jingū taima". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "神宮大麻と神宮暦 (Jingū taima to Jingu-reki)". Ise Jingu Official Website (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "第14章 神宮大麻・暦". Fukushima Jinjachō Official Website (in Japanese). Fukushima Jinjachō. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "三重)伊勢神宮で「大麻用材伐始祭」". Asahi Shimbun Digital. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "お神札". Ise Jingū Official Website. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "教えてお伊勢さん (Oshiete O-Isesan)". Ise Jingū Official Website. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "お神札、お守りについて (Ofuda, omamori ni tsuite)". Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honchō). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "神棚のまつり方". Jinja no Hiroba. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Household-shrine". Wagokoro. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "御神札・御守・撤饌等の扱い方について". 城山八幡宮 (Shiroyama Hachiman-gū) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "お守りやお札の取り扱い". ja兵庫みらい (JA Hyōgo Mirai) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "Ofuda (talisman)". Green Shinto. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ "お神札(ふだ)のまつり方 (Ofuda no matsurikata)". Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honchō). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "お神札・神棚について". Tokyo Jinjachō (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ Toyozaki, Yōko (2007). 「日本の衣食住」まるごと事典 (Who Invented Natto?). IBC Publishing. pp. 59–61.

- ^ "神棚と神拝作法について教えて下さい。". 武蔵御嶽神社 (Musashi Mitake Jinja) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ "神棚の祀り方と参拝方法". 熊野ワールド【神々の宿る熊野の榊】 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ "奥津彦命・奥津姫命のご利益や特徴". 日本の神様と神社 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ "奥津日子神". 神魔精妖名辞典. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ "烏枢沙摩明王とは". うすさま.net (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ Matsuura, Thersa (2019-11-24). "The Great Horned Master (Tsuno Daishi) (Ep. 43)". Uncanny Japan. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ Groner, Paul (2002). Ryōgen and Mount Hiei: Japanese Tendai in the Tenth Century. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 297–298.

- ^ Reader, Ian; Tanabe, George J. (1998). Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan. University of Hawaii Press. p. 196.

- ^ "御神札について教えてください。". 武蔵御嶽神社 (Musashi Mitake Jinja) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "お守りの扱い方". 由加山蓮台寺 (Yugasan Rendai-ji) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "知っているようで知らない 神社トリビア②". Jinjya.com. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "どんど焼き". 菊名神社 (Kikuna Jinja) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "どんど焼き【どんと祭り】古いお札やお守りの処理の仕方". 豆知識PRESS (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "霊験無比なる「太上秘法鎮宅霊符」". 星田妙見宮 (Hoshida Myōken-gū) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ 国書刊行会 (Kokusho Hankōkai), ed. (1915). 信仰叢書 (Shinkō-sōsho) (in Japanese). 国書刊行会 (Kokusho Hankōkai). pp. 354–363.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "京のおまじない「逆さ札」と天下の大泥棒・石川五右衛門". WebLeaf (in Japanese). Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ "「十二月廿五日」五右衛門札貼り替え 嘉穂劇場". Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). 2017-12-26. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

Further reading[]

- Nelson, Andrew N., Japanese-English Character Dictionary, Charles E. Tuttle Company: Publishers, Tokyo, 1999, ISBN 4-8053-0574-6

- Masuda Koh, Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, Kenkyusha Limited, Tokyo, 1991, ISBN 4-7674-2015-6

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ofuda. |

- Amulets

- Shinto cult objects

- Talismans

- Exorcism in Buddhism