One Hundred Ghost Stories

One Hundred Ghost Stories (百物語, Hyaku monogatari) is a series of ukiyo-e woodblock prints made by Katsushika Hokusai in the Yūrei-zu genre in c. 1830. There are only five prints in this series, though as its title suggests, the publisher, , and Hokusai wanted to make a series of one hundred prints.[1][2] Hokusai was in his seventies when he worked on this series, and though his most famous impressions are of nature, he was aware of the beliefs of the Edo period and depicts ghosts from well-known stories, many of which were also famous kabuki plays. Each print represents one story, that could be recited during the game of Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai.

Background[]

The series is made in the tradition of Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai (A Gathering of One Hundred Supernatural Tales), a popular Japanese game played at night, when people would meet to share folklore ghost stories and their own anecdotes. Stories were told one by one with a light of a hundred candles, blowing out a candle after each story.[2][1] The game was first played by samurai as a test for courage, but quickly became widespread.[3] With each candle going down, it was believed that a channel for ghosts and spirits was created, the one that they could use to travel into the world of living. After all the candles were extinguished, it was believed that something ghostly could occur.[4]

The game originated as a religious ritual; stated that "these gatherings may have had their origin during the medieval period in Hyakuza hodan (One Hundred Buddhist Stories), in which it was widely believed that miracles would happen after telling one hundred Buddhist stories over one hundred days".[5]

Prints[]

The Plate Mansion (Sara-yashiki)

The Laughing Hannya (Warai-hannya)

The Ghost of Oiwa (Oiwa-san)

Kohada Koheiji (こはだ小平二)

Obsession (Shûnen)

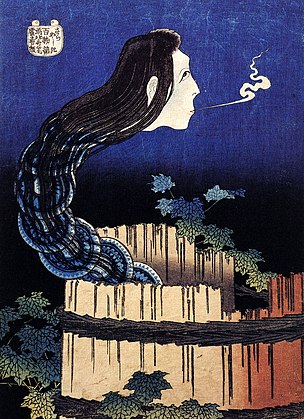

The Plate Mansion (Sara-yashiki)[]

The legend from 17th century tells a story of a maid, Okiku, who broke valuable Korean plates and was thrown to a well by her master;[2] another version tells that Okiku throws herself in despair down a well.[6] Another version tells that Okiku broke only one plate; after she was thrown into a well, she turned into a ghost, Yūrei, and the neighbours heard her voice from that well every night, repeating "One... Two... Three... Eight... Nine... I can’t find last one..."[7][8] After the rumors of this spread, the house was confiscated from the master. When a monk added "ten" for Okiku's count, she finally disappeared.[7] Yet another version tells that Okiku worked for a samurai Aoyama Tessan from Himeji Castle, and after she rejected him Aoyama deceived her into believing that she lost one of the valuable plates. Aoyama offered his forgiveness if Okiku becomes his lover; after her refusal he throws her into a well. She then returned as a spirit to count her plates every night, "shrieking on the tenth count".[9]

The tale was well known in Japan, and has a variety of forms; the most popular version established in 1795, when Japan "suffered an infestation of a type of worm found in old wells that became known as the "Okiku bug" (Okiku mushi). This worm, covered with thin threads making it look as though it had been bound, was widely believed to be a reincarnation of Okiku."[2][10]

Hokusai draw Okiku's spirit as a serpent whose body is made of a plates.[9] Kassandra Diaz noted that while Okiku is a spirit, in Hokusai's print she "resembles a rokurokubi or nure-onna. An intelligent decision on his part as these yokai, much rarer than yurei, make this Okiku scarier."[9]

The story was very popular, and many ukiyo-e artists made impressions based on it.

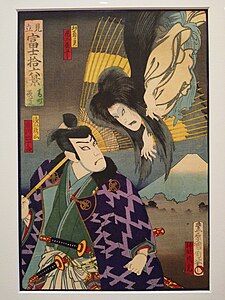

Utagawa Kunisada, 1843-1847

Utagawa Hiroshige

Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900)

Toyohara Kunichika, 1892

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1890

The Laughing Hannya (Warai-hannya)[]

In this print Hokusai combined two folklore monsters, a hannya, old woman was believed to be changed into a demon because of deep-seated jealousy, and a yamanba ("mountain woman"), a demon believed to devour kidnapped children.[9] In the print the monster is shown reveling in her demonic meal of a live infant.[2][10] The story is from the Nagano region folklore.[7] Warai-hannya was also called the Laughing Demoness or Ogress.[4]

Hokusai divided the painting with a crescent arc that acts as a divisional line before human world and a supernatural, ghost world.[4] It is similar to the window on Hokusai's print View from Massaki of Suijin Shrine, Uchigawa Inlet, and Sekiya (1857). As a print is painted from inside a home, placing the hannya outside "brings it into the viewer's everyday life".[9]

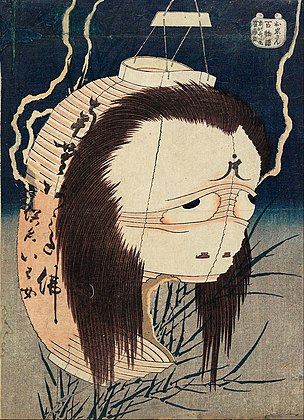

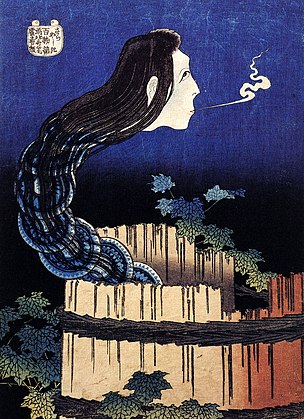

The Ghost of Oiwa (Oiwa-san)[]

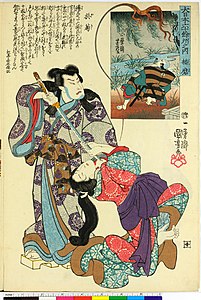

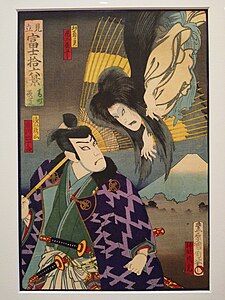

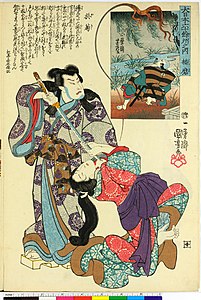

The story originated as a play for kabuki theater, Yotsuya Kaidan, and was written in 1825 by Tsuruya Nanboku IV.[12] Several versions of this story exist. In one, young girl Oume falls in love with the married samurai Tamiya Iemon, and her friends try to get rid of his wife Oiwa with a gift of poisonous face cream. When Iemon abandons his mutilated wife, it made her mad with grief. In her hysteria she runs and trips onto a sword, cursing Iemon with her dying breath — and then adopting various forms to haunt him, including a paper lantern.[2][10] In another version, unemployed samurai Iemon married a daughter from a warrior family, who needs a man to succeed their family name. He then poisoned and killed his young wife, and she started to haunt Iemon as a ghost.[13] Another version tells that Iemon wanted to kill his wife and to marry into a wealthy family, and that he had hired assassin who killed her and dump the body into a river.[14] One more version tells that Oiwa got smallpox as a child, but her husband, Iemon, didn't mind about her face, and it was his master who wanted him to divorce and marry with his granddaughter; when Iemon did it, Oiwa died and turned into a ghost, cursing the family. When people built a shrine to relief her feeling, the ghost disappeared.[7]

Paper lanterns were used in the Buddhist tradition ; people bring them to their family member's graves to welcome their spirits. In Hokusai's print ghost of Oiwa possessed a lantern, in accord with a belief of the lantern usage for communication with ancestral spirits. On the lantern there is an inscription: "Praise Amida / The Woman Named O-iwa". The calligraphy is not typical of that used for paper lanterns, called .[9] Kassandra Diaz writes that:

The creases of the lantern fold over her exhausted eyes, which point to the Buddhist seed syllable on her forehead. The syllable refers to Gobujo, a form of Yama, the lord of the underworld and judge of the dead. This may be a mark bestowed upon Oiwa by Yama, who punished her by returning her to the world in her "new body".[9]

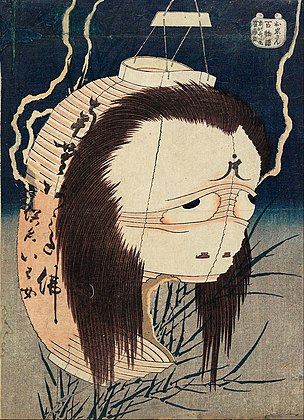

Kohada Koheiji (こはだ小平二)[]

Print shows a scene from a Japanese legend about a man drowned in a swamp by his wife and her lover and who returns to haunt them in revenge; it depicts a skeletal ghost with flames around him who returned to scare the couple while they are in bed together under a mosquito net.[2][10] Another version tells that Kohada Koheiji was a kabuki actor for the Morita-za theater; as he couldn't get any good role, he was cast as a yurei, and he had only such roles after that. His wife Otsuka was ashamed of him, and together with her lover, another actor called Adachi Sakuro, murdered Kohada and throw his body into a swamp.[9] Kassandra Diaz noted that "He wears juzu beads which were used in Buddhist prayer by rubbing between both hands. Regardless of whether they were Kohada's or part of his yurei kabuki costume, the beads symbolize religious piety, which Otsuki and Adachi clearly disregarded."[9]

The writer Santō Kyōden, also known as the ukiyo-e artist Kitao Masanobu, developed the Koheiji story in his 1803 novel, (Fukushû kidan Asaka-numa). The story was set on a real basis, as Koheiji was a real murder victim.[5] In 1808, the story was staged on the kabuki theater.[1][5]

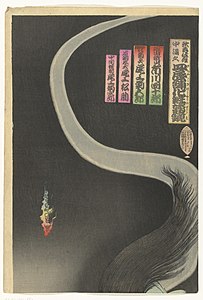

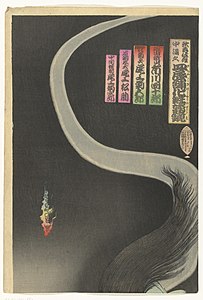

Obsession (Shûnen)[]

Print shows a snake wrapped around a memorial tablet (ihai) for a Buddhist altar (traditionally placed on an altar at the home of the deceased); the snake represents obsessive jealousy that continues after death.[2][10] Offerings and the water near the altar tablet are for the dead.[7] The snake appears to be a ghost of a deceased person, for whom the offerings were made. The print was also called "Implacable Malevolence".[4] The memorial tablet is from 1831 to 1845, when the Tenpō famine killed many people in Japan, including the person on the print.[9]

The middle line identifies the posthumous name given to the Buddhist – Momonji (茂問爺), a yokai who appears as a bestial old man who assaults travelers on dark roads. This terror is far worse than witnessing a yokai – becoming one themselves after death.[9]

On the bowl there is a Buddhist swastika, called manji in Japanese; Hokusai used it as a pen name. "Thus, another interpretation is that the deceased is Hokusai himself, whose obsession with the supernatural world has ironically turned him into one." The two symbols on the print are used as a contrasts, a snake is a symbol of obsession, and the leaf on water – a symbol of a peaceful mind.[9]

Reception and analysis[]

Ghosts and everyday life[]

Kassandra Diaz wrote that in the series Hokusai integrated ghost stories into everyday life:

An Edoite can never walk comfortably past Oiwa Tamiya Inari Shrine, Morita-za, castle wells, serpent shrines, or mountains without recalling Hokusai’s disturbing yokai. Thus, this series creates an intimate experience for each viewer to project the scary stories onto their immediate surroundings.[9]

Scholars wrote that it was typical of the period for people to believe in the ghosts from the stories, "there seems to be a convergent point in Japanese society where individuals from all walks of life seem to unite in their belief of the supernatural". Hokusai himself could believe in ghosts, he was in the Nichiren Buddhist sect, and probably believed that "he would one day walk the earth as a phantom". Shortly before his death, Hokusai wrote a haiku: "Though as a ghost, I shall lightly tread the summer fields". Sumpter wrote that "this vibrant depiction of death gone a-hunting speaks to Hokusai’s belief in the supernatural".[5] states that "Hokusai must have believed in ghosts to have created such realistic images of them".[5]

Women's role[]

Each print in some way represents a woman who committed something that goes against the Buddhist teachings, so yokai stories "functioned as religious and political allegory to subjugate women in their societal roles".[9]

The story of Oiwa, a wife killed by her husband, was interpreted to be a tale of marital relations:

The story teaches of the consequences of betrayal, cowardice and selfishness. Betrayal, because the hideous appearance of Oiwa was caused by the consumption of a potion given to her by the father of another woman who was in love with Iyemon; the potion was disguised as a medicine to help Oiwa recover from giving birth but caused a facial disfigurement, which subsequently led Iyemon to abandon Oiwa, disgusted. Cowardice and selfishness are indicated through the actions of Iyemon who, rather than admitting that he no longer wished to remain married to Oiwa, began to abuse her in the hope that she would leave him, thus leading Oiwa to commit suicide in despair at the rejection. The consequences of this immoral treatment of Iyemon and others towards Oiwa are insanity and death, which translate into unhappiness and loss.[4]

Social instability[]

Sara Sumpter wrote that in a single Kohada Koheiji print Hokusai shows the nation's struggle in the Edo period; "Through this single grotesque woodblock print, Hokusai illustrates the social discontent of the Edo society with a flawed system that was soon to fall." In her view, ghost stories (and prints) appeared because of this period's repression and restrictions, and were "metaphorical social commentaries". In her view, the popularity of ghost stories in the Edo period was "an indication of a larger social movement at hand". After the unification of the country under the Tokugawa Shogunate made civil wars "a thing of the past ... people could regard strange phenomena and terror as entertainment". Besides, ghost stories were a way for the people to express themselves during the times of censorship and repression.[5]

This graphic depiction was crucial not just for invoking the level of terror associated with the ghost story, but for creating an ingeniously hidden metaphor of Edo society. With a ruling warrior class exerting an iron grip on the populace, ordinary citizens had virtually no rights [...] In this context, Kohada Koheiji is no longer just the ghost of a man wrongly killed, seeking his much deserved justice. He represents the deadening existence that plagued the commoner classes of the Edo period. As he peers through the netting of his victims’ tent, the unseen antagonists become not just Koheiji's victims, but the victims of the Tokugawa government—a mass of nameless protagonists persecuted by grim reforms and restrictions. The sadness and fear expressed in the Ghost of Kohada Koheiji [...] would ultimately tell the tale—not just of a man murdered—but of a social system fallen.[5]

Modern views[]

Timothy Clark, Head of the Japanese Section in the Department of Asia at the British Museum, wrote that the "print series on the theme was the occasion for the elderly Hokusai to weave together powerful currents that had long gestated in his art of hyper-realism, macabre fantasy and even a certain humour."[1] He also noted that in Kohada Koheiji print the origins of the modern Japanese manga are visible. "It is vivid and sensational with a fantasy that is very much part of the later manga tradition".[15] The Guardian called Kohada Koheiji "Funny Bones", and wrote that the picture was likely "designed to induce shrieks of laughter as much as fright".[16]

See also[]

Media related to Hyaku Monogatari by Katsushika Hokusai at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hyaku Monogatari by Katsushika Hokusai at Wikimedia Commons- List of legendary creatures from Japan

References[]

- ^ a b c d "Kohada Koheiji". The British Museum. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Hokusai's Ghost Stories (ca. 1830)". The Public Domain Review. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0

- ^ Diego, Cucinelli (1 January 2015). "Ghost from the Past: The Fortune of hyaku monogatari in Post-Meiji Japan". Understanding New Perspectives of Spirituality: 97–105. doi:10.1163/9781848883772_010. ISBN 9781848883772.

- ^ a b c d e ROWE, SAMANTHA, SUE,CHRISTINA (2015) The Yokai Imagination of Symbolism: The Role of Japanese Ghost Imagery in late 19th & early 20th Century European Art Volumes I-III, Durham theses, Durham University.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sumpter, Sara (19 May 2020). "Katsushika Hokusai's Ghost of Kohada Koheiji : Image from a Falling Era". Presentica. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Some Japanese Ghosts by Christopher Benfey | NYR Daily | The New York Review of Books". nybooks.com. NYR Daily. 11 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Hokusai's horror ghosts artworks (ukiyo-e)". Masterpieces of Japanese Culture. 31 December 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Sarayashiki (The House of Broken Plates), from the series One Hundred Ghost Tales". Freer Gallery of Art & Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Diaz, Kassandra (1 July 2021). "Hokusai's Supernatural World". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Search results for Photo, Print, Drawing, Hyaku Monogatari, Available Online". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Kabuki Actor Arashi Rikan II as Iemon Confronted by an Image of His Murdered Wife". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Kennelly, Paul. "Realism in Kabuki of the early nineteenth century. A case study" (PDF). Proceedings of the Pacific Rim Conference in Transcultural Aesthetics: 157. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-14.

- ^ "The Ghost of Oiwa, Katsushika Hokusai; Publisher: Tsuruya Kiemon – Minneapolis Institute of Art". collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "The Ghost of Oiwa by Hokusai". japaneseprints.org. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Katsushika Hokusai's later life to feature in British Museum show". the Guardian. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Hokusai's Kohada Koheiji: the age-old pastime of telling ghost stories". The Guardian. 26 May 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Works by Hokusai

- Ukiyo-e print series

- Japanese ghosts

- Japanese folklore

- Japanese horror fiction

- Edo-period works