Oogonium

| Oogonium | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009867 |

| FMA | 83673 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

An oogonium (plural oogonia) is a small diploid cell which, upon maturation, forms a primordial follicle in a female fetus or the female (haploid or diploid) gametangium of certain thallophytes.

In the mammalian fetus[]

Oogonia are formed in large numbers by mitosis early in fetal development from primordial germ cells. In humans they start to develop between weeks 4 and 8 and are present in the fetus between weeks 5 and 30.

Structure[]

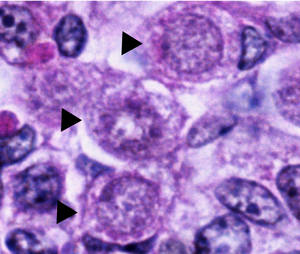

Normal oogonia in human ovaries are spherical or ovoid in shape and are found amongst neighboring somatic cells and oocytes at different phases of development. Oogonia can be distinguished from neighboring somatic cells, under an electron microscope, by observing their nuclei. Oogonial nuclei contain randomly dispersed fibrillar and granular material whereas the somatic cells have a more condensed nucleus that creates a darker outline under the microscope. Oogonial nuclei also contain dense prominent nucleoli. The chromosomal material in the nucleus of mitotically dividing oogonia shows as a dense mass surrounded by vesicles or double membranes.[1]

The cytoplasm of oogonia appears similar to that of the surrounding somatic cells and similarly contains large round mitochondria with lateral cristae. The Endoplasmic Reticulum (E.R.) of oogonia, however, is very underdeveloped and is made up of several small vesicles. Some of these small vesicles contain cisternae with ribosomes and are found located near the golgi apparatus.[1]

Oogonia that are undergoing degeneration appear slightly different under the electron microscope. In these oogonia, the chromosomes clump together into an indistinguishable mass within the nucleus and the mitochondria and E.R. appear to be swollen and disrupted. Degenerating oogonia are usually found partially or wholly engulfed in neighboring somatic cells, identifying phagocytosis as the mode of elimination.[1]

Development and differentiation[]

In the blastocyst of the mammalian embryo, primordial germ cells arise from proximal epiblasts under the influence of extra-embryonic signals. These germ cells then travel, via amoeboid movement, to the genital ridge and eventually into the undifferentiated gonads of the fetus.[2] During the 4th or 5th week of development, the gonads begin to differentiate. In the absence of the Y chromosome, the gonads will differentiate into ovaries. As the ovaries differentiate, ingrowths called cortical cords develop. This is where the primordial germ cells collect.[3][4]

During the 6th to 8th week of female (XX) embryonic development, the primordial germ cells grow and begin to differentiate into oogonia. Oogonia proliferate via mitosis during the 9th to 22nd week of embryonic development. There can be up to 600,000 oogonia by the 8th week of development and up to 7,000,000 by the 5th month.[3]

Eventually, the oogonia will either degenerate or further differentiate into primary oocytes through asymmetric division. Asymmetric division is a process of mitosis in which one oogonium divides unequally to produce one daughter cell that will eventually become an oocyte through the process of oogenesis, and one daughter cell that is an identical oogonium to the parent cell. This occurs during the 15th week to the 7th month of embryonic development.[2] Most oogonia have either degenerated or differentiated into primary oocytes by birth.[3][5]

Primary oocytes will undergo oogenesis in which they enter meiosis. However, primary oocytes are arrested in prophase 1 of the first meiosis and remain in that arrested stage until puberty begins in the female adult.[6] This is in contrast to male primordial germ cells which are arrested in the spermatogonial stage at birth and do not enter into spermatogenesis and meiosis to produce primary spermatocytes until puberty in the adult male.[3]

Regulation of oogonia differentiation and entry into oogenesis[]

The regulation and differentiation of germ cells into primary gametocytes ultimately depends on the sex of the embryo and the differentiation of the gonads. In female mice, the protein RSPO1 is responsible for the differentiation of female (XX) gonads into ovaries. RSPO1 activates the β-catenin signaling pathway by up-regulating Wnt4 which is an essential step in ovary differentiation. Research has shown that ovaries lacking Rspo1 or Wnt4 will exhibit sex reversal of the gonads, the formation of ovotestes and the differentiation of somatic sertoli cells, which aid in the development of sperm.[4]

After female (XX) germ cells collect in the undifferentiated gonads, the up-regulation of Stra8 is required for germ cell differentiation into an oogonium and eventually enter meiosis. One major factor that contributes to the up-regulation of Stra8, is the initiation of the β-Catenin signaling pathway via RSPO1, which is also responsible for ovary differentiation. Since RSPO1 is produced in somatic cells, this protein acts on germ cells in a paracrine mode. Rspo1, however, is not the only factor in Stra8 regulation. Many other factors are under scrutiny and this process is still being evaluated.[4]

Oogonial stem cells[]

It is theorized that oogonia either degenerate or differentiate into primary oocytes which enter oogenesis and are halted in prophase I of the first meiosis post partum. Therefore, it is believed that adult mammalian females lack a population of germ cells that can renew or regenerate, and instead have a large population of primary oocytes that are arrested in the first meiosis until puberty.[2] At puberty, one primary oocyte will continue meiosis each menstrual cycle. Because there is an absence of regenerating germ cells and oogonia in the human, the number of primary oocytes dwindles after each menstrual cycle until menopause, when the female no longer has a population of primary oocytes.[2]

Recent research, however, has identified that renewable oogonia may be present in the lining of the female ovaries of humans, primates and mice.[2][7][8] It is thought that these germ cells might be necessary for the upkeep of the reproductive follicles and oocyte development, well into adulthood. It has also been discovered that some stem cells may migrate from the bone marrow to the ovaries as a source of extra-genial germ cells. These mitotically active germ cells found in mammalian adults were identified by tracking several markers that were common in oocytes. These potential renewable germ cells were identified as positive for these essential oocyte markers.[2]

The discovery of these active germ cells and oogonia in the adult female could be very useful in the advancement of fertility research and treatment of infertility.[2][8] Germ cells have been extracted, isolated and grown successfully in vitro.[8] These germ cells have been used to restore fertility in mice by promoting follicle generation and upkeep in previously infertile mice. There is also research being done on possible germ line regeneration in primates. Mitotically active human female germ cells could be very beneficial to a new method of embryonic stem cell development that involves a nuclear transfer into a zygote. Using these functional oogonia may help to create patient-specific stem cell lines using this method.[2]

Controversy[]

There is a significant controversy regarding existence of mammalian oogonial stem cells. The controversy lies in negative data that has originated from many laboratories in the United States. Multiple approaches to verify the existence of oogonial stem cells have yielded negative results, and no research group in United States has been able to reproduce initial findings.[9][10][11]

In certain thallophytes[]

In phycology and mycology, oogonium refers to a female gametangium if the union of the male (motile or non-motile) and the female gamete takes place within this structure.[12][13]

In Oomycota and some other organisms, the female oogonia, and the male equivalent antheridia, are a result of sexual sporulation, i.e. the development of structures within which meiosis will occur. The haploid nuclei (gametes) are formed by meiosis within the antheridia and oogonia, and when fertilization occurs, a diploid oospore is produced which will eventually germinate into the diploid somatic stage of the thallophyte life cycle.[14]

In many algae (e.g., Chara), the main plant is haploid; oogonia and antheridia form and produce haploid gametes. The only diploid part of the life cycle is the spore (fertilized egg cell), which undergoes meiosis to form haploid cells that develop into new plants. This is a haplontic life cycle (with zygotic meiosis).

Structure[]

The oogonia of certain Thallophyte species[which?] are usually round or ovoid, with contents are divided into several uninucleate oospheres. This is in contrast to the male antheridia which are elongate and contain several nuclei.[14]

In heterothallic species, the oogonia and antheridia are located on hyphal branches of different thallophyte colonies. Oogonia of this species can only be fertilized by antheridia from another colony and ensures that self-fertilization is impossible.[clarification needed] In contrast, homothallic species display the oogonia and antheridia on either the same hyphal branch or on separate hyphal branches but within the same colony.[14]

Fertilization[]

In a common mode of fertilization found in certain species of Thallophytes, the antheridia will bind with the oogonia. The antheridia will then form fertilization tubes connecting the antheridial cytoplasm with each oosphere within the oogonia. A haploid nucleus (gamete) from the antheridium will then be transferred through the fertilization tube into the oosphere, and fuse with the oosphere’s haploid nucleus forming a diploid oospore. The oospore is then ready to germinate and develop into an adult diploid somatic stage.[14]

References[]

- ^ a b c Baker, T.G.; L. L. Franchi (1967). "The Fine Structures of Oogonia Oocytes in Human Ovaries". Journal of Cell Science. 2 (2): 213–224. doi:10.1242/jcs.2.2.213. PMID 4933750. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Germ Stem Cells, A Scientific Summary". New Jersey Medical School. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Richard E. (1997). Human Reproductive Biology, 2nd Ed. San Diego: Academic Press, Elsevier. pp. 26–40, 90–107, 117–125. ISBN 0-12-389775-0.

- ^ a b c Chassot, A. A.; Gregoire, E. P.; Lavery, R.; Taketo, M. M.; de Rooij, D. G.; et al. (2011). "RSPO1/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway Regulates Oogonia Differentiation and Entry into Meiosis in the Mouse Fetal Ovary". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25641. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625641C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025641. PMC 3185015. PMID 21991325.

- ^ "Human Emryology, Embryogenesis". Module 3, Gametogenesis. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Genetics, Meiosis and Gaetogenesis". www.emich.edu. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Telfer, Evelyn E.; David F. Albertini (2012). "The Quest for Human Ovarian Stem Cells". Nature Medicine. 18 (3): 353–354. doi:10.1038/nm.2699. PMID 22395699. S2CID 1289213.

- ^ a b c White, Yvonne A. R.; Dori C Woods; Yashushi Takai; OSamu Ishihara; Hiroyuki Seki; Jonathan L. Tilly (2012). "Oocyte Formation by Mitotically Active Germ Cells Purified From Ovaries of Reprodutive-Age Women". Nature Medicine. 18 (3): 413–421. doi:10.1038/nm.2669. PMC 3296965. PMID 22366948.

- ^ Zhang, H; Panula, S; Petropoulos, S; Edsgärd, D; Busayavalasa, K; Liu, L; Li, X; Risal, S; Shen, Y; Shao, J; Liu, M; Li, S; Zhang, D; Zhang, X; Gerner, RR; Sheikhi, M; Damdimopoulou, P; Sandberg, R; Douagi, I; Gustafsson, JÅ; Liu, L; Lanner, F; Hovatta, O; Liu, K (Oct 2015). "Adult human and mouse ovaries lack DDX4-expressing functional oogonial stem cells". Nat. Med. 21 (10): 1116–8. doi:10.1038/nm.3775. hdl:10616/44674. PMID 26444631. S2CID 2949653.

- ^ Lei, L; Spradling, AC (2013). "Female mice lack adult germ-line stem cells but sustain oogenesis using stable primordial follicles". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110 (21): 8585–90. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.8585L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1306189110. PMC 3666718. PMID 23630252.

- ^ Horan, CJ; Williams, SA (2017). "Oocyte stem cells: fact or fantasy?". Reproduction. 154 (1): R23–R35. doi:10.1530/REP-17-0008. PMID 28389520.

- ^ Stegenga, H. Bolton, J.J. and Anderson, R.J. 1997. Seaweeds of the South African West Coast. Bolus Herbarium, University of Cape Town. ISBN 0-7992-1793-X

- ^ Smyth, G.M. 1955. Cryptogamic Botany. vol. 1. McGraw-Hill Book Company

- ^ a b c d "Sexual Sporulation in Oomycota". Archived from the original on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

External links[]

- Germ cells