Outsider music

Outsider music (from "outsider art") is music created by self-taught or naïve musicians. The term is usually applied to musicians who have little or no traditional musical experience, who exhibit childlike qualities in their music, or who suffer from intellectual disabilities or mental illnesses. The term was popularized in the 1990s by journalist and WFMU DJ Irwin Chusid.[1]

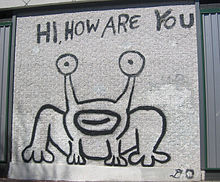

Outsider musicians often overlap with lo-fi artists, since their work is rarely captured in professional recording studios. Examples include Daniel Johnston, Wesley Willis, and Jandek, who each became the subjects of documentary films in the 2000s.[2]

Etymology[]

The term "outsider music" is traced to the definitions of "outsider art" and "naïve art".[3] "Outsider art" is rooted in the 1920s French concept of "L'Art Brut" ("raw art"). In 1972, academic Roger Cardinal introduced "outsider art" as the American counterpart of "L'Art Brut", which originally referred to work created exclusively by children or the mentally ill.[4] The word "outsider" began to be applied to music cultures as early as 1959, with respect to jazz,[5] and to rock as early as 1979.[6] In the 1970s, "outsider music" was also a "favorite epithet" in music criticism in Europe.[7] By the 1980s and 1990s, "outsider" was common in the cultural lexicon and was synonymous with "self-taught", "untrained", and "primitive".[4]

Definition and scope[]

Although outsider music has existed since before written history, it was not until the advent of sound reproduction and music exchange networks that such a genre was recognized.[8] Music journalist Irwin Chusid is credited with adapting "outsider art" for music in a 1996 article for the Tower Records publication Pulse!.[4] As a DJ on the New Jersey radio station WFMU in the 1980s, he had been an influential figure in independent music scenes.[1] In 2000, he authored a book titled Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music, which attempted to introduce and market outsider music as a genre.[8] He summarized the concept thus:

... there are countless "unintentional renegades," performers who lack [an] overt self-consciousness about their art. As far as they're concerned, what they're doing is "normal." And despite paltry incomes and dismal record sales, they're happy to be in the same line of work as Celine Dion and Andrew Lloyd Webber. ... Their vocals sound melodically adrift; their rhythms stumble. They seem harmonically without anchor. Their instrumental proficiency may come across as laughably incompetent. ... They get little or no commercial radio exposure, their followings are limited, and they have roughly the same likelihood of attaining mainstream success that a possum has of skittering safely across a six-lane freeway. ... The outsiders in this book, for the most part, lack self-awareness. They don't boldly break the rules, because they don't know there are rules.[9]

As was common with journalists who championed musical primitivism in the 1980s,[10] Chusid considered outsiders more "authentic" than artists whose music is "exploited through conventional music channels" and "revised, remodeled, and re-coifed; touched-up and tweaked; Photoshopped and focus-grouped" by the time it reaches the listener, to the point that it is "Music by Committee". On the other hand, outsider artists have much "greater individual control over the final creative contour", either because of a low budget or because of their "inability or unwillingness to cooperate with or trust anyone but themselves."[9]

Outsider music does not generally include avant-garde music, world music, songs recorded solely for their novelty value, or anything self-consciously camp or kitsch; Chusid uses the term "incorrect music" for music that is intentionally recorded to draw bad reactions, from non-musician celebrity entertainers attempting to cross over into music, or from artists who are talented and self-aware enough not to produce such music but do so anyway. Works are usually sourced from home recordings or independent recording studios "with no quality control".[8] In Songs in the Key of Z, Chusid explicitly avoided discussing "unpopular", "uncommercial", or "underground" artists, and disqualified "just about anyone who could keep an orchestra or band together."[9] He did include a few acts in the definition that broke through to mainstream fame as novelty acts; Tiny Tim, for example, is included despite a consistent three-decade career in the music industry that included a major chart hit, Joe Meek was one of the United Kingdom's most influential and successful sound engineers of the 1960s, and the Legendary Stardust Cowboy had a brief moment of widespread fame in the 1960s with several national television appearances.[9]

Chusid posited that the biggest-selling artist fitting of the "outsider" label could be Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, citing the widely circulated bootlegs of his unreleased 1970s and 1980s demos. However, "considering the level on which he's been embraced by the public, it's difficult to make a case for him as an outsider."[11] Similarly, Chusid avoided covering "other outré icons who have achieved wide public exposure, such as Frank Zappa, Sun Ra, Marilyn Manson, and the Butthole Surfers, to name a few. Many (if not most) major figures in the arts began their rise to stardom as nominal outsiders."[11]

Cultural resonance and influence[]

Chusid credited outsider musicians for the existence of dub reggae ("invented by an outsider, Lee "Scratch" Perry"), the K Records and Sub Pop record labels, and the "punk/new-wave/no-wave upheaval that undermined prog-rock and airbrush-pop in the mid- to late-1970s [and] hyped itself with the defiant notion that anyone―regardless of technical proficiency or lack thereof―could make music as long as it represented genuine, naturalistic self-expression."[9] Specific acts that "significantly contributed―directly and indirectly―to contemporary popular music" include Syd Barrett, Captain Beefheart, the Shaggs, Harry Partch, Robert Graettinger, and Daniel Johnston.[11] Conversely, the book Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music (2007) argues that "few of the outsiders praised by their fans can be called innovators; most of them are simply naïve."[14]

Skip Spence's Oar (1969), Beefheart's Trout Mask Replica (produced by Frank Zappa, 1969), and Barrett's The Madcap Laughs (1970), according to music historian John Encarnacao, "were particularly important in helping to define a framework through which outsider recordings are understood ... [They] seeded many ideas and practices, affirming them as desirable in the context of rock mythology."[15] In 1969, Zappa co-founded Bizarre Records, a label dedicated to "musical and sociological material that the important record companies would probably not allow you to hear," and approached the production of Trout Mask Replica like an anthropological field recording.[16] Beefheart was not on the Bizarre label, but Larry "Wild Man" Fischer was. Fischer was a street performer discovered by Zappa and is sometimes regarded as "the grandfather of outsider music".[12] In the liner notes of the 1968 album An Evening with Wild Man Fischer, Zappa writes: "Please listen to this album several times before you decide whether or not you like it or what Wild Man Fischer is all about. He has something to say to you, even though you might not want to hear it." According to musicologist Adam Harper, the writing prefigures similar commentary on "the also mentally ill Daniel Johnston."[17]

After a 1980 reissue on NRBQ's Red Rooster Records (distributed by Rounder Records), The Shaggs attracted notoriety for their 1969 album Philosophy of the World, which received prominent national coverage. It was referred to as "the worst rock album ever made" by the New York Times and later championed in published lists such as "the 100 most influential alternative albums of all time", "the greatest garage recordings of the 20th century", and "the fifty most significant indie records".[18] Lester Bangs famously praised the band as better than the Beatles, and Zappa also held the band in high regard, much higher than the Shaggs themselves, who were embarrassed by the record.[19] In the 1990s, interest in outsider music was spurred by books such as Incredibly Strange Music (1994) and compilations devoted to obscure musicians such as B. J. Snowden, Wesley Willis, Lucia Pamela, and Eilert Pilarm.[9]

Lo-fi music[]

Outsider musicians tend to overlap with "lo-fi" artists since their work is rarely captured in professional studios.[1] Harper credits the discourse surrounding Daniel Johnston and Jandek with "form[ing] a bridge between 1980s primitivism and the lo-fi indie rock of the 1990s. ... both musicians introduced the notion that lo-fi was not just acceptable but the special context of some extraordinary and brilliant musicians."[20] Critics frequently write about Johnston's "pure and childlike soul" and describe him as the "Brian Wilson" of lo-fi.[21]

R. Stevie Moore, who pioneered lo-fi/DIY music, was affiliated with Irwin Chusid as well as being associated with the "outsider" tag. He recalled "always ha[ving] the dilemma that [Irwin] did not want to present me as an outsider, like a Wesley Willis or a Daniel Johnston, or these people that are touched in the head and have a certain gift. I love outsider music ... but they have no concept as to how to write or arrange a Brian Wilson song." (Moore's father, Bob Moore, was a consummate musical insider, having worked as a session musician with the Nashville A-Team.)[22]

See also[]

Related topics

- Avant-pop

- Creativity and mental illness

- Folk art

- New Weird America

- Underground music

Documentary films

- The Daddy of Rock 'n' Roll (2003) (about Wesley Willis)

- The Devil and Daniel Johnston (2005)

- Jandek on Corwood (2003)

- Derailroaded: Inside the Mind of Wild Man Fischer (2005)

- Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of Smile (2005)

References[]

- ^ a b c Harper, Adam (2014). Lo-Fi Aesthetics in Popular Music Discourse (PDF). Wadham College. pp. 48, 190. Retrieved March 10, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Harper 2014, p. 347.

- ^ Encarnacao, John (2016). Punk Aesthetics and New Folk: Way Down the Old Plank Road. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-317-07321-5.

- ^ a b c Plasketes, George (2016). B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-317-17113-3.

- ^ Charles Winick, "The Use of Drugs by Jazz Musicians", Social Problems 7, no. 3 (Winter 1959–1960): 240–53. Citation on 250.

- ^ Bernice Martin, "The Sacralization of Disorder: Symbolism in Rock Music", Sociological Analysis 40, no. 2 (Summer 1979): 87–124. Citation on 116.

- ^ Zdenka Kapko-Foretić, "Kölnska škola avangarde", Zvuk: Jugoslavenska muzička revija, 1980 no. 2:50–55. Citation on 54.

- ^ a b c Misiroglu, Gina, ed. (2015). American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in U.S. History. Routledge. pp. 541–542. ISBN 978-1-317-47729-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Chusid 2000.

- ^ Harper 2014, pp. 48, 53, 63–64.

- ^ a b c Chusid, Irwin (2000). Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music. Chicago Review Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-1-56976-493-0.

- ^ a b Fox, Margalit (June 17, 2011). "Wild Man Fischer, Outsider Musician, Dies at 66". The New York Times.

- ^ "I'm crazy for you... but not that crazy". The Observer. March 18, 2006.

- ^ Barker, Hugh; Taylor, Yuval (2007). Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music. W. W. Norton. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-393-06078-2.

- ^ Encarnacao 2016, p. 105.

- ^ Harper 2014, p. 110.

- ^ Harper 2014, p. 100.

- ^ Harper 2014, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Fishman, Howard (August 30, 2017). "The Shaggs Reunion Concert Was Unsettling, Beautiful, Eerie, and Will Probably Never Happen Again". Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Harper 2014, p. 180.

- ^ McNamee, David (August 10, 2009). "The myth of Daniel Johnston's genius". The Guardian.

- ^ Ingram, Matthew (June 2012). "Here Comes the Flood". The Wire. No. 340.

- Outsider music

- Naïve art

- Indie music