Oxford University Press

| |

| Parent company | University of Oxford |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1586 |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Headquarters location | Oxford, England |

| Key people | Nigel Portwood, CEO |

| Publication types | Books, journals, sheet music |

| Imprints | Clarendon Press |

| No. of employees | 6,000 |

| Official website | global |

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and the second oldest after Cambridge University Press.[1][2][3] It is a department of the University of Oxford and is governed by a group of 15 academics appointed by the vice-chancellor known as the delegates of the press. They are headed by the secretary to the delegates, who serves as OUP's chief executive and as its major representative on other university bodies. Oxford University Press has had a similar governance structure since the 17th century.[4] The Press is located on Walton Street, Oxford, opposite Somerville College, in the inner suburb of Jericho.

Early history[]

The university became involved in the print trade around 1480, and grew into a major printer of Bibles, prayer books, and scholarly works.[5] OUP took on the project that became the Oxford English Dictionary in the late 19th century, and expanded to meet the ever-rising costs of the work.[6] As a result, the last hundred years has seen Oxford publish further English and bilingual dictionaries, children's books, school textbooks, music, journals, the World's Classics series, and a range of English language teaching texts. Moves into international markets led to OUP opening its own offices outside the United Kingdom, beginning with New York City in 1896.[7] With the advent of computer technology and increasingly harsh trading conditions, the Press's printing house at Oxford was closed in 1989, and its former paper mill at Wolvercote was demolished in 2004. By contracting out its printing and binding operations, the modern OUP publishes some 6,000 new titles around the world each year.[citation needed]

The first printer associated with Oxford University was Theoderic Rood. A business associate of William Caxton, Rood seems to have brought his own wooden printing press to Oxford from Cologne as a speculative venture, and to have worked in the city between around 1480 and 1483. The first book printed in Oxford, in 1478,[8] an edition of Rufinus's Expositio in symbolum apostolorum, was printed by another, anonymous, printer. Famously, this was mis-dated in Roman numerals as "1468", thus apparently pre-dating Caxton. Rood's printing included John Ankywyll's Compendium totius grammaticae, which set new standards for teaching of Latin grammar.[9]

After Rood, printing connected with the university remained sporadic for over half a century. Records of surviving work are few, and Oxford did not put its printing on a firm footing until the 1580s; this succeeded the efforts of Cambridge University, which had obtained a licence for its press in 1534. In response to constraints on printing outside London imposed by the Crown and the Stationers' Company, Oxford petitioned Elizabeth I of England for the formal right to operate a press at the university. The chancellor, Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, pleaded Oxford's case. Some royal assent was obtained, since the printer began work, and a decree of Star Chamber noted the legal existence of a press at "the universitie of Oxforde" in 1586.[10]

17th century: William Laud and John Fell[]

Oxford's chancellor, Archbishop William Laud, consolidated the legal status of the university's printing in the 1630s. Laud envisaged a unified press of world repute. Oxford would establish it on university property, govern its operations, employ its staff, determine its printed work, and benefit from its proceeds. To that end, he petitioned Charles I for rights that would enable Oxford to compete with the Stationers' Company and the King's Printer, and obtained a succession of royal grants to aid it. These were brought together in Oxford's "Great Charter" in 1636, which gave the university the right to print "all manner of books".[11] Laud also obtained the "privilege" from the Crown of printing the King James or Authorized Version of Scripture at Oxford.[12] This "privilege" created substantial returns in the next 250 years, although initially it was held in abeyance. The Stationers' Company was deeply alarmed by the threat to its trade and lost little time in establishing a "Covenant of Forbearance" with Oxford. Under this, the Stationers paid an annual rent for the university not to exercise its complete printing rights – money Oxford used to purchase new printing equipment for smaller purposes.[13]

Laud also made progress with internal organization of the Press. Besides establishing the system of Delegates, he created the wide-ranging supervisory post of "Architypographus": an academic who would have responsibility for every function of the business, from print shop management to proofreading. The post was more an ideal than a workable reality, but it survived (mostly as a sinecure) in the loosely structured Press until the 18th century. In practice, Oxford's Warehouse-Keeper dealt with sales, accounting, and the hiring and firing of print shop staff.[14]

Laud's plans, however, hit terrible obstacles, both personal and political. Falling foul of political intrigue, he was executed in 1645, by which time the English Civil War had broken out. Oxford became a Royalist stronghold during the conflict, and many printers in the city concentrated on producing political pamphlets or sermons. Some outstanding mathematical and Orientalist works emerged at this time—notably, texts edited by Edward Pococke, the Regius Professor of Hebrew—but no university press on Laud's model was possible before the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660.[15]

It was finally established by the vice-chancellor, John Fell, Dean of Christ Church, Bishop of Oxford, and Secretary to the Delegates. Fell regarded Laud as a martyr, and was determined to honour his vision of the Press. Using the provisions of the Great Charter, Fell persuaded Oxford to refuse any further payments from the Stationers and drew all printers working for the university onto one set of premises. This business was set up in the cellars of the new Sheldonian Theatre, where Fell installed printing presses in 1668, making it the university's first central print shop.[16] A type foundry was added when Fell acquired a large stock of typographical punches and matrices from the Dutch Republic—the so-called "Fell Types". He also induced two Dutch typefounders, Harman Harmanz and Peter de Walpergen, to work in Oxford for the Press.[17] Finally, defying the Stationers' demands, Fell personally leased the right to print from the university in 1672, in partnership with Thomas Yate, Principal of Brasenose, and Sir Leoline Jenkins, Principal of Jesus College.[18]

Fell's scheme was ambitious. Besides plans for academic and religious works, in 1674 he began to print a broadsheet calendar, known as the Oxford Almanack. Early editions featured symbolic views of Oxford, but in 1766 these gave way to realistic studies of city or university.[19] The Almanacks have been produced annually without interruption from Fell's time to the present day.[20]

Following the start of this work, Fell drew up the first formal programme for the university's printing. Dating from 1675, this document envisaged hundreds of works, including the Bible in Greek, editions of the and works of the Church Fathers, texts in Arabic and Syriac, comprehensive editions of classical philosophy, poetry, and mathematics, a wide range of medieval scholarship, and also "a history of insects, more perfect than any yet Extant."[21] Though few of these proposed titles appeared during Fell's life, Bible printing remained at the forefront of his mind. A full variant Greek text of Scripture proved impossible, but in 1675 Oxford printed a quarto King James edition, carrying Fell's own textual changes and spellings. This work only provoked further conflict with the Stationers' Company. In retaliation, Fell leased the university's Bible printing to three rogue Stationers, Moses Pitt, Peter Parker, and Thomas Guy, whose sharp commercial instincts proved vital to fomenting Oxford's Bible trade.[22] Their involvement, however, led to a protracted legal battle between Oxford and the Stationers, and the litigation dragged on for the rest of Fell's life. He died in 1686.[23]

18th century: Clarendon Building and Blackstone[]

Yate and Jenkins predeceased Fell, leaving him with no obvious heir to oversee the print shop. As a result, his will left the partners' stock and lease in trust to Oxford University, and charged them with keeping together "my founding Materialls of the Press."[24] Fell's main trustee was the Delegate Henry Aldrich, Dean of Christ Church, who took a keen interest in the decorative work of Oxford's books. He and his colleagues presided over the end of Parker and Guy's lease, and a new arrangement in 1691 whereby the Stationers leased the whole of Oxford's printing privilege, including its unsold scholarly stock. Despite violent opposition from some printers in the Sheldonian, this ended the friction between Oxford and the Stationers, and marked the effective start of a stable university printing business.[25]

In 1713, Aldrich also oversaw the Press moving to the Clarendon Building. This was named in honour of Oxford University's Chancellor, Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon. Oxford lore maintained its construction was funded by proceeds from his book The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England (1702–04). In fact, most of the money came from Oxford's new Bible printer John Baskett—and the Vice-Chancellor William Delaune defaulted with much of the proceeds from Clarendon's work. In any event, the result was Nicholas Hawksmoor's beautiful but impractical structure beside the Sheldonian in Broad Street. The Press worked here until 1830, with its operations split into the so-called Learned Side and Bible Side in different wings of the building.[26]

Generally speaking, the early 18th century marked a lull in the Press's expansion. It suffered from the absence of any figure comparable to Fell, and its history was marked by ineffectual or fractious individuals such as the Architypographus and antiquary Thomas Hearne, and the flawed project of Baskett's first Bible, a gorgeously designed volume strewn with misprints, and known as the Vinegar Bible after a glaring typographical error in St. Luke. Other printing during this period included Richard Allestree's contemplative texts, and Thomas Hanmer's six-volume edition of Shakespeare, (1743–44).[27] In retrospect, these proved relatively minor triumphs. They were products of a university press that had come to embody increasing muddle, decay, and corrupt practice, and relied increasingly on leasing of its Bible and prayer book work to survive.[citation needed]

The business was rescued by the intervention of a single Delegate, William Blackstone. Disgusted by the chaotic state of the Press, and antagonized by the Vice-Chancellor George Huddesford, Blackstone subjected the print shop to close scrutiny, but his findings on its confused organization and sly procedures met with only "gloomy and contemptuous silence" from his colleagues, or "at best with a languid indifference." In disgust, Blackstone forced the university to confront its responsibilities by publishing a lengthy letter he had written to Huddesford's successor, Thomas Randolph in May 1757. Here, Blackstone characterized the Press as an inbred institution that had given up all pretence of serving scholarship, "languishing in a lazy obscurity … a nest of imposing mechanics." To cure this disgraceful state of affairs, Blackstone called for sweeping reforms that would firmly set out the Delegates' powers and obligations, officially record their deliberations and accounting, and put the print shop on an efficient footing.[28] Nonetheless, Randolph ignored this document, and it was not until Blackstone threatened legal action that changes began. The university had moved to adopt all of Blackstone's reforms by 1760.[29]

By the late 18th century, the Press had become more focused. Early copyright law had begun to undercut the Stationers, and the university took pains to lease out its Bible work to experienced printers. When the American War of Independence deprived Oxford of a valuable market for its Bibles, this lease became too risky a proposition, and the Delegates were forced to offer shares in the Press to those who could take "the care and trouble of managing the trade for our mutual advantage." Forty-eight shares were issued, with the university holding a controlling interest.[30] At the same time, classical scholarship revived, with works by Jeremiah Markland and Peter Elmsley, as well as early 19th-century texts edited by a growing number of academics from mainland Europe – perhaps the most prominent being August Immanuel Bekker and Karl Wilhelm Dindorf. Both prepared editions at the invitation of the Greek scholar Thomas Gaisford, who served as a Delegate for 50 years. During his time, the growing Press established distributors in London, and employed the bookseller Joseph Parker in Turl Street for the same purposes in Oxford. Parker also came to hold shares in the Press itself.[31]

This expansion pushed the Press out of the Clarendon building. In 1825 the Delegates bought land in Walton Street. Buildings were constructed from plans drawn up by Daniel Robertson and Edward Blore, and the Press moved into them in 1830.[32] This site remains the main office of OUP in the 21st century, at the corner of Walton Street and Great Clarendon Street, northwest of Oxford city centre.

19th century: Price and Cannan[]

The Press now entered an era of enormous change. In 1830, it was still a joint-stock printing business in an academic backwater, offering learned works to a relatively small readership of scholars and clerics. The Press was the product of "a society of shy hypochondriacs," as one historian put it.[33] Its trade relied on mass sales of cheap Bibles, and its Delegates were typified by Gaisford or Martin Routh. They were long-serving classicists, presiding over a learned business that printed 5 or 10 titles each year, such as Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon (1843), and they displayed little or no desire to expand its trade.[34] Steam power for printing must have seemed an unsettling departure in the 1830s.[35]

At this time, Thomas Combe joined the Press and became the university's Printer until his death in 1872. Combe was a better business man than most Delegates, but still no innovator: he failed to grasp the huge commercial potential of India paper, which grew into one of Oxford's most profitable trade secrets in later years.[36] Even so, Combe earned a fortune through his shares in the business and the acquisition and renovation of the bankrupt paper mill at Wolvercote. He funded schooling at the Press and the endowment of St. Barnabas Church in Oxford.[37] Combe's wealth also extended to becoming the first patron of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and he and his wife Martha bought most of the group's early work, including The Light of the World by William Holman Hunt.[38] Combe showed little interest, however, in producing fine printed work at the Press.[39] The most well-known text associated with his print shop was the flawed first edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, printed by Oxford at the expense of its author Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) in 1865.[40]

It took the 1850 Royal Commission on the workings of the university and a new Secretary, Bartholomew Price, to shake up the Press.[41] Appointed in 1868, Price had already recommended to the university that the Press needed an efficient executive officer to exercise "vigilant superintendence" of the business, including its dealings with Alexander Macmillan, who became the publisher for Oxford's printing in 1863 and in 1866 helped Price to create the Clarendon Press series of cheap, elementary school books – perhaps the first time that Oxford used the Clarendon imprint.[42] Under Price, the Press began to take on its modern shape. By 1865 the Delegacy had ceased to be 'perpetual,' and evolved into five perpetual and five junior posts filled by appointment from the university, with the Vice Chancellor a Delegate ex officio: a hothouse for factionalism that Price deftly tended and controlled.[43] The university bought back shares as their holders retired or died.[44] Accounts' supervision passed to the newly created Finance Committee in 1867.[45] Major new lines of work began. To give one example, in 1875, the Delegates approved the series Sacred Books of the East under the editorship of Friedrich Max Müller, bringing a vast range of religious thought to a wider readership.[46]

Equally, Price moved OUP towards publishing in its own right. The Press had ended its relationship with Parker's in 1863 and in 1870 bought a small London bindery for some Bible work.[47] Macmillan's contract ended in 1880, and wasn't renewed. By this time, Oxford also had a London warehouse for Bible stock in Paternoster Row, and in 1880 its manager Henry Frowde (1841–1927) was given the formal title of Publisher to the University. Frowde came from the book trade, not the university, and remained an enigma to many. One obituary in Oxford's staff magazine The Clarendonian admitted, "Very few of us here in Oxford had any personal knowledge of him."[48] Despite that, Frowde became vital to OUP's growth, adding new lines of books to the business, presiding over the massive publication of the Revised Version of the New Testament in 1881[49] and playing a key role in setting up the Press's first office outside Britain, in New York City in 1896.[50]

Price transformed OUP. In 1884, the year he retired as Secretary, the Delegates bought back the last shares in the business.[51] The Press was now owned wholly by the university, with its own paper mill, print shop, bindery, and warehouse. Its output had increased to include school books and modern scholarly texts such as James Clerk Maxwell's A Treatise on Electricity & Magnetism (1873), which proved fundamental to Einstein's thought.[52] Simply put, without abandoning its traditions or quality of work, Price began to turn OUP into an alert, modern publisher. In 1879, he also took on the publication that led that process to its conclusion: the huge project that became the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).[53]

Offered to Oxford by James Murray and the Philological Society, the "New English Dictionary" was a grand academic and patriotic undertaking. Lengthy negotiations led to a formal contract. Murray was to edit a work estimated to take 10 years and to cost approximately £9,000.[54] Both figures were wildly optimistic. The Dictionary began to appear in print in 1884, but the first edition was not completed until 1928, 13 years after Murray's death, at a cost of around £375,000.[55] This vast financial burden and its implications landed on Price's successors.[citation needed]

The next Secretary struggled to address this problem. Philip Lyttelton Gell was appointed by the Vice-Chancellor Benjamin Jowett in 1884. Despite his education at Balliol and a background in London publishing, Gell found the operations of the Press incomprehensible. The Delegates began to work around him, and the university finally dismissed Gell in 1897.[56] The Assistant Secretary, Charles Cannan, took over with little fuss and even less affection for his predecessor: "Gell was always here, but I cannot make out what he did."[57]

Cannan had little opportunity for public wit in his new role. An acutely gifted classicist, he came to the head of a business that was successful in traditional terms but now moved into uncharted terrain.[58] By themselves, specialist academic works and the undependable Bible trade could not meet the rising costs of the Dictionary and Press contributions to the University Chest. To meet these demands, OUP needed much more revenue. Cannan set out to obtain it. Outflanking university politics and inertia, he made Frowde and the London office the financial engine for the whole business. Frowde steered Oxford rapidly into popular literature, acquiring the World's Classics series in 1906. The same year saw him enter into a so-called "joint venture" with Hodder & Stoughton to help with the publication of children's literature and medical books.[59] Cannan insured continuity to these efforts by appointing his Oxford protégé, the Assistant Secretary Humphrey S. Milford, to be Frowde's assistant. Milford became Publisher when Frowde retired in 1913, and ruled over the lucrative London business and the branch offices that reported to it until his own retirement in 1945.[60] Given the financial health of the Press, Cannan ceased to regard scholarly books or even the Dictionary as impossible liabilities. "I do not think the University can produce enough books to ruin us," he remarked.[61]

His efforts were helped by the efficiency of the print shop. Horace Hart was appointed as Controller of the Press at the same time as Gell, but proved far more effective than the Secretary. With extraordinary energy and professionalism, he improved and enlarged Oxford's printing resources, and developed Hart's Rules as the first style guide for Oxford's proofreaders. Subsequently, these became standard in print shops worldwide.[62] In addition, he suggested the idea for the Clarendon Press Institute, a social club for staff in Walton Street. When the Institute opened in 1891, the Press had 540 employees eligible to join it, including apprentices.[63] Finally, Hart's general interest in printing led to him cataloguing the "Fell Types", then using them in a series of Tudor and Stuart facsimile volumes for the Press, before ill health led to his death in 1915.[64] By then, OUP had moved from being a parochial printer into a wide-ranging, university-owned publishing house with a growing international presence.[citation needed]

London business[]

Frowde regularly remitted money back to Oxford, but he privately felt that the business was undercapitalized and would pretty soon become a serious drain on the university's resources unless put on a sound commercial footing. He himself was authorized to invest money up to a limit in the business but was prevented from doing so by family troubles. Hence his interest in overseas sales, for by the 1880s and 1890s there was money to be made in India, while the European book market was in the doldrums. But Frowde's distance from the Press's decision-making meant he was incapable of influencing policy unless a Delegate spoke for him. Most of the time Frowde did whatever he could within the mandate given him by the Delegates. In 1905, when applying for a pension, he wrote to , the then Vice Chancellor, that during the seven years when he had served as manager of the Bible Warehouse the sales of the London Business had averaged about £20,000 and the profits £1,887 per year. By 1905, under his management as Publisher, the sales had risen to upwards of £200,000 per year and the profits in that 29 years of service averaged £8,242 per year.[citation needed]

Conflict over secretaryship[]

Price, trying in his own way to modernize the Press against the resistance of its own historical inertia, had become overworked and by 1883 was so exhausted as to want to retire. Benjamin Jowett had become vice chancellor of the university in 1882. Impatient of the endless committees that would no doubt attend the appointment of a successor to Price, Jowett extracted what could be interpreted as permission from the delegates and headhunted Philip Lyttelton Gell, a former student acolyte of his, to be the next secretary to the delegates. Gell was making a name for himself at the publishing firm of Cassell, Petter and Galpin, a firm regarded as scandalously commercial by the delegates. Gell himself was a patrician who was unhappy with his work, where he saw himself as catering to the taste of "one class: the lower middle",[citation needed] and he grasped at the chance of working with the kind of texts and readerships OUP attracted.[citation needed]

Jowett promised Gell golden opportunities, little of which he actually had the authority to deliver. He timed Gell's appointment to coincide with both the Long Vacation (from June to September) and the death of Mark Pattison, so potential opposition was prevented from attending the crucial meetings. Jowett knew the primary reason why Gell would attract hostility was that he had never worked for the Press nor been a delegate, and he had sullied himself in the city with raw commerce. His fears were borne out. Gell immediately proposed a thorough modernising of the Press with a marked lack of tact, and earned himself enduring enemies. Nevertheless, he was able to do a lot in tandem with Frowde, and expanded the publishing programmes and the reach of OUP until about 1898. Then his health broke down under the impossible work conditions he was being forced to endure by the Delegates' non-cooperation. The delegates then served him with a notice of termination of service that violated his contract. However, he was persuaded not to file suit and to go quietly.[65][full citation needed]

The delegates were not opposed primarily to his initiatives, but to his manner of executing them and his lack of sympathy with the academic way of life. In their view the Press was, and always would be, an association of scholars. Gell's idea of "efficiency" appeared to violate that culture, although subsequently a very similar programme of reform was put into practice from the inside.[citation needed]

20th–21st century[]

Charles Cannan, who had been instrumental in Gell's removal, succeeded Gell in 1898, and Humphrey S. Milford, his younger colleague, effectively succeeded Frowde in 1907. Both were Oxford men who knew the system inside out, and the close collaboration with which they worked was a function of their shared background and worldview. Cannan was known for terrifying silences, and Milford had an uncanny ability, testified to by Amen House employees, to 'disappear' in a room rather like a Cheshire cat, from which obscurity he would suddenly address his subordinates and make them jump. Whatever their reasons for their style of working, both Cannan and Milford had a very hardnosed view of what needed to be done, and they proceeded to do it. Indeed, Frowde knew within a few weeks of Milford's entering the London office in [1904] that he would be replaced. Milford, however, always treated Frowde with courtesy, and Frowde remained in an advisory capacity till 1913. Milford rapidly teamed up with J. E. Hodder Williams of Hodder and Stoughton, setting up what was known as the Joint Account for the issue of a wide range of books in education, science, medicine and also fiction. Milford began putting in practice a number of initiatives, including the foundations of most of the Press's global branches.[citation needed]

Development of overseas trade[]

Milford took responsibility for overseas trade almost at once, and by 1906 he was making plans to send a traveller to India and the Far East jointly with Hodder and Stoughton. N. Graydon (first name unknown) was the first such traveller in 1907, and again in 1908 when he represented OUP exclusively in India, the Straits and the Far East. A.H. Cobb replaced him in 1909, and in 1910 Cobb functioned as a travelling manager semi-permanently stationed in India. In 1911, E. V. Rieu went out to East Asia via the Trans-Siberian Railway, had several adventures in China and Russia, then came south to India and spent most of the year meeting educationists and officials all over India. In 1912, he arrived again in Bombay, now known as Mumbai. There he rented an office in the dockside area and set up the first overseas Branch.[citation needed]

In 1914, Europe was plunged into turmoil. The first effects of the war were paper shortages and losses and disturbances in shipping, then quickly a dire lack of hands as the staff were called up and went to serve on the field. Many of the staff including two of the pioneers of the Indian branch were killed in action. Curiously, sales through the years 1914 to 1917 were good and it was only towards the end of the war that conditions really began pinching.[citation needed]

Rather than bringing relief from shortages, the 1920s saw skyrocketing prices of both materials and labour. Paper especially was hard to come by, and had to be imported from South America through trading companies. Economies and markets slowly recovered as the 1920s progressed. In 1928, the Press's imprint read 'London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leipzig, Toronto, Melbourne, Cape Town, Bombay, Calcutta, Madras and Shanghai'. Not all of these were full-fledged branches: in Leipzig there was a depot run by H. Bohun Beet, and in Canada and Australia there were small, functional depots in the cities and an army of educational representatives penetrating the rural fastnesses to sell the Press's stock as well as books published by firms whose agencies were held by the Press, very often including fiction and light reading. In India, the Branch depots in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta were imposing establishments with sizable stock inventories, for the Presidencies themselves were large markets, and the educational representatives there dealt mostly with upcountry trade. The Depression of 1929 dried profits from the Americas to a trickle, and India became 'the one bright spot' in an otherwise dismal picture. Bombay was the nodal point for distribution to the Africas and onward sale to Australasia, and people who trained at the three major depots moved later on to pioneer branches in Africa and South East Asia.[66]

The Press's experience of World War II was similar to World War I except that Milford was now close to retirement and 'hated to see the young men go'. The London blitz this time was much more intense and the London Business was shifted temporarily to Oxford. Milford, now extremely unwell and reeling under a series of personal bereavements, was prevailed upon to stay till the end of the war and keep the business going. As before, everything was in short supply, but the U-boat threat made shipping doubly uncertain, and the letterbooks are full of doleful records of consignments lost at sea. Occasionally an author, too, would be reported missing or dead, as well as staff who were now scattered over the battlefields of the globe. DORA, the Defence of the Realm Act, required the surrender of all nonessential metal for the manufacture of armaments, and many valuable electrotype plates were melted down by government order.[citation needed]

With the end of the war Milford's place was taken by Geoffrey Cumberlege. This period saw consolidation in the face of the breakup of the Empire and the post-war reorganization of the Commonwealth. In tandem with institutions like the British Council, OUP began to reposition itself in the education market. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o in his book Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedom records how the Oxford Readers for Africa with their heavily Anglo-centric worldview struck him as a child in Kenya.[67] The Press has evolved since then to be one of the largest players in a globally expanding scholarly and reference book market.[citation needed]

North America[]

The North American branch was established in 1896 at 91 Fifth Avenue in New York City primarily as a distribution branch to facilitate the sale of Oxford Bibles in the United States. Subsequently, it took over marketing of all books of its parent from Macmillan. Its very first original publication, The Life of Sir William Osler, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1926. Since that time, OUP USA published fourteen more Pulitzer Prize–winning books.[citation needed]

The North American branch grew in sales between 1928 and 1936, eventually becoming one of the leading university presses in the United States. It is focused on scholarly and reference books, Bibles, and college and medical textbooks. In the 1990s, this office moved from 200 Madison Avenue (a building it shared with Putnam Publishing) to 198 Madison Avenue, the former B. Altman and Company Building.[68]

South America[]

In December 1909 Cobb returned and rendered his accounts for his Asia trip that year. Cobb then proposed to Milford that the Press join a combination of firms to send commercial travellers around South America, to which Milford in principle agreed. Cobb obtained the services of a man called Steer (first name unknown) to travel through Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Chile and possibly other countries as well, with Cobb to be responsible for Steer. Hodder & Stoughton opted out of this venture, but OUP went ahead and contributed to it.[citation needed]

Indian branch[]

When OUP arrived on Indian shores, it was preceded by the immense prestige of the Sacred Books of the East, edited by Friedrich Max Müller, which had at last reached completion in 50 ponderous volumes. While actual purchase of this series was beyond the means of most Indians, libraries usually had a set, generously provided by the government of India, available on open reference shelves, and the books had been widely discussed in the Indian press. Although there had been plenty of criticism of them, the general feeling was that Max Müller had done India a favour by popularising ancient Asian (Persian, Arabic, Indian and Sinic) philosophy in the West.[69][full citation needed] This prior reputation was useful, but the Indian Branch was not primarily in Bombay to sell Indological books, which OUP knew already sold well only in America. It was there to serve the vast educational market created by the rapidly expanding school and college network in British India. In spite of disruptions caused by war, it won a crucial contract to print textbooks for the Central Provinces in 1915 and this helped to stabilize its fortunes in this difficult phase. E. V. Rieu could not longer delay his callup and was drafted in 1917, the management then being under his wife Nellie Rieu, a former editor for the Athenaeum 'with the assistance of her two British babies.' It was too late to have important electrotype and stereotype plates shipped to India from Oxford, and the Oxford printing house itself was overburdened with government printing orders as the empire's propaganda machine got to work. At one point non-governmental composition at Oxford was reduced to 32 pages a week.[citation needed]

By 1919, Rieu was very ill and had to be brought home. He was replaced by and Noel Carrington. Noel was the brother of Dora Carrington, the artist, and even got her to illustrate his Stories Retold edition of Don Quixote for the Indian market. Their father Charles Carrington had been a railway engineer in India in the nineteenth century. Noel Carrington's unpublished memoir of his six years in India is in the Oriental and India Office Collections of the British Library. By 1915 there were makeshift depots at Madras and Calcutta. In 1920, Noel Carrington went to Calcutta to set up a proper branch. There he became friendly with Edward Thompson who involved him in the abortive scheme to produce the 'Oxford Book of Bengali Verse'.[70][full citation needed] In Madras, there was never a formal branch in the same sense as Bombay and Calcutta, as the management of the depot there seems to have rested in the hands of two local academics.[citation needed]

East and South East Asia[]

OUP's interaction with this area was part of their mission to India, since many of their travellers took in East and South East Asia on their way out to or back from India. Graydon on his first trip in 1907 had travelled the 'Straits Settlements' (largely the Federated Malay States and Singapore), China, and Japan, but was not able to do much. In 1909, A. H. Cobb visited teachers and booksellers in Shanghai, and found that the main competition there was cheap books from America, often straight reprints of British books.[71] The copyright situation at the time, subsequent to the Chace Act of 1891, was such that American publishers could publish such books with impunity although they were considered contraband in all British territories. To secure copyright in both territories publishers had to arrange for simultaneous publication, an endless logistical headache in this age of steamships. Prior publication in any one territory forfeited copyright protection in the other.[72]

The Press had problems with Henzell, who were irregular with correspondence. They also traded with Edward Evans, another Shanghai bookseller. Milford observed, 'we ought to do much more in China than we are doing' and authorized Cobb in 1910 to find a replacement for Henzell as their representative to the educational authorities.[citation needed] That replacement was to be Miss M. Verne McNeely, a redoubtable lady who was a member of the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, and also ran a bookshop. She looked after the affairs of the Press very capably and occasionally sent Milford boxes of complimentary cigars. Her association with OUP seems to date from 1910, although she did not have exclusive agency for OUP's books. Bibles were the major item of trade in China, unlike India where educational books topped the lists, even if Oxford's lavishly produced and expensive Bible editions were not very competitive beside cheap American ones.[citation needed]

Japan was a much less well-known market to OUP, and a small volume of trade was carried out largely through intermediaries. The Maruzen company was by far the largest customer, and had a special arrangement regarding terms. Other business was routed through H. L. Griffiths, a professional publishers' representative based in Sannomiya, Kobe. Griffiths travelled for the Press to major Japanese schools and bookshops and took a 10 percent commission.[citation needed] Edmund Blunden had been briefly at the University of Tokyo and put the Press in touch with the university booksellers, Fukumoto Stroin. One important acquisition did come from Japan, however: A. S. Hornby's Advanced Learner's Dictionary. It also publishes textbooks for the primary and secondary education curriculum in Hong Kong. The Chinese-language teaching titles are published with the brand Keys Press (啟思出版社).[citation needed]

Africa[]

Some trade with East Africa passed through Bombay.[73] Following a period of acting mostly as a distribution agent for OUP titles published in the UK, in the 1960s OUP Southern Africa started publishing local authors, for the general reader, but also for schools and universities, under its Three Crowns Books imprint. Its territory includes Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Namibia, as well as South Africa, the biggest market of the five.[citation needed]

OUP Southern Africa is now one of the three biggest educational publishers in South Africa, and focuses its attention on publishing textbooks, dictionaries, atlases and supplementary material for schools, and textbooks for universities. Its author base is overwhelmingly local, and in 2008 it entered into a partnership with the university to support scholarships for South Africans studying postgraduate degrees.[citation needed]

Establishment of Music Department[]

Prior to the twentieth century, the Press at Oxford had occasionally printed a piece of music or a book relating to musicology. It had also published the Yattendon Hymnal in 1899 and, more significantly, the first edition of The English Hymnal in 1906, under the editorship of Percy Dearmer and the then largely unknown Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir William Henry Hadow's multi-volume Oxford History of Music had appeared between 1901 and 1905. Such musical publishing enterprises, however, were rare: "In nineteenth-century Oxford the idea that music might in any sense be educational would not have been entertained",[74] and few of the Delegates or former Publishers were themselves musical or had extensive music backgrounds.[citation needed]

In the London office, however, Milford had musical taste, and had connections particularly with the world of church and cathedral musicians. In 1921, Milford hired Hubert J. Foss, originally as an assistant to Educational Manager V. H. Collins. In that work, Foss showed energy and imagination. However, as Sutcliffe says, Foss, a modest composer and gifted pianist, "was not particularly interested in education; he was passionately interested in music."[74] When shortly thereafter Foss brought to Milford a scheme for publishing a group of essays by well-known musicians on composers whose works were frequently played on the radio, Milford may have thought of it as less music-related than education-related. There is no clear record of the thought process whereby the Press would enter into the publishing of music for performance. Foss's presence, and his knowledge, ability, enthusiasm, and imagination may well have been the catalyst bringing hitherto unconnected activities together in Milford's mind, as another new venture similar to the establishment of the overseas branches.[75]

Milford may not have fully understood what he was undertaking. A fiftieth anniversary pamphlet published by the Music Department in 1973 says that OUP had "no knowledge of the music trade, no representative to sell to music shops, and—it seems—no awareness that sheet music was in any way a different commodity from books."[76] However intentionally or intuitively, Milford took three steps that launched OUP on a major operation. He bought the Anglo-French Music Company and all its facilities, connections, and resources. He hired Norman Peterkin, a moderately well-known musician, as full-time sales manager for music. And in 1923, he established as a separate division the Music Department, with its own offices in Amen House and with Foss as first Musical Editor. Then, other than general support, Milford left Foss largely to his own devices.[77]

Foss responded with incredible energy. He worked to establish "the largest possible list in the shortest possible time",[78] adding titles at the rate of over 200 a year; eight years later there were 1,750 titles in the catalogue. In the year of the department's establishment, Foss began a series of inexpensive but well edited and printed choral pieces under the series title "Oxford Choral Songs". This series, under the general editorship of W. G. Whittaker, was OUP's first commitment to the publishing of music for performance, rather than in book form or for study. The series plan was expanded by adding the similarly inexpensive but high-quality "Oxford Church Music" and "Tudor Church Music" (taken over from the Carnegie UK Trust); all these series continue today. The scheme of contributed essays Foss had originally brought to Milford appeared in 1927 as the Heritage of Music (two more volumes would appear over the next thirty years). Percy Scholes's Listener's Guide to Music (originally published in 1919) was similarly brought into the new department as the first of a series of books on music appreciation for the listening public.[75] Scholes's continuing work for OUP, designed to match the growth of broadcast and recorded music, plus his other work in journalistic music criticism, would be later comprehensively organized and summarized in the Oxford Companion to Music.[citation needed]

Perhaps most importantly, Foss seemed to have a knack for finding new composers of what he regarded as distinctively English music, which had broad appeal to the public. This concentration provided OUP two mutually reinforcing benefits: a niche in music publishing unoccupied by potential competitors, and a branch of music performance and composition that the English themselves had largely neglected. Hinnells proposes that the early Music Department's "mixture of scholarship and cultural nationalism" in an area of music with largely unknown commercial prospects was driven by its sense of cultural philanthropy (given the Press's academic background) and a desire to promote "national music outside the German mainstream."[79]

In consequence, Foss actively promoted the performance and sought publication of music by Ralph Vaughan Williams, William Walton, Constant Lambert, Alan Rawsthorne, Peter Warlock (Philip Heseltine), Edmund Rubbra and other English composers. In what the Press called "the most durable gentleman's agreement in the history of modern music,"[78] Foss guaranteed the publication of any music that Vaughan Williams would care to offer them. In addition, Foss worked to secure OUP's rights not only to music publication and live performance, but the "mechanical" rights to recording and broadcast. It was not at all clear at the time how significant these would become. Indeed, Foss, OUP, and a number of composers at first declined to join or support the Performing Right Society, fearing that its fees would discourage performance in the new media. Later years would show that, to the contrary, these forms of music would prove more lucrative than the traditional venues of music publishing.[80]

Whatever the Music Department's growth in quantity, breadth of musical offering, and reputation amongst both musicians and the general public, the whole question of financial return came to a head in the 1930s. Milford as London publisher had fully supported the Music Department during its years of formation and growth. However, he came under increasing pressure from the Delegates in Oxford concerning the continued flow of expenditures from what seemed to them an unprofitable venture. In their mind, the operations at Amen House were supposed to be both academically respectable and financially remunerative. The London office "existed to make money for the Clarendon Press to spend on the promotion of learning."[81] Further, OUP treated its book publications as short-term projects: any books that did not sell within a few years of publication were written off (to show as unplanned or hidden income if in fact they sold thereafter). In contrast, the Music Department's emphasis on music for performance was comparatively long-term and continuing, particularly as income from recurring broadcasts or recordings came in, and as it continued to build its relationships with new and upcoming musicians. The Delegates were not comfortable with Foss's viewpoint: "I still think this word 'loss' is a misnomer: is it not really capital invested?" wrote Foss to Milford in 1934.[82]

Thus it was not until 1939 that the Music Department showed its first profitable year.[83] By then, the economic pressures of the Depression as well as the in-house pressure to reduce expenditures, and possibly the academic background of the parent body in Oxford, combined to make OUP's primary musical business that of publishing works intended for formal musical education and for music appreciation—again the influence of broadcast and recording.[83] This matched well with an increased demand for materials to support music education in British schools, a result of governmental reforms of education during the 1930s.[note 1] The Press did not cease to search out and publish new musicians and their music, but the tenor of the business had changed. Foss, suffering personal health problems, chafing under economic constraints plus (as the war years drew on) shortages in paper, and disliking intensely the move of all the London operations to Oxford to avoid The Blitz, resigned his position in 1941, to be succeeded by Peterkin.[84]

Closure of Oxuniprint[]

On 27 August 2021, OUP will close Oxuniprint, its printing division. It will result in the loss of 20 jobs and follows a "continued decline in sales" aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The closure will mark the "final chapter" of OUP's centuries-long history of printing.[85]

Museum[]

The Oxford University Press Museum is located on Great Clarendon Street, Oxford. Visits must be booked in advance and are led by a member of the archive staff. Displays include a 19th-century printing press, the OUP buildings, and the printing and history of the Oxford Almanack, Alice in Wonderland and the Oxford English Dictionary.[citation needed]

Clarendon Press[]

OUP came to be known as "(The) Clarendon Press" when printing moved from the Sheldonian Theatre to the Clarendon Building in Broad Street in 1713. The name continued to be used when OUP moved to its present site in Oxford in 1830. The label "Clarendon Press" took on a new meaning when OUP began publishing books through its London office in the early 20th century. To distinguish the two offices, London books were labelled "Oxford University Press" publications, while those from Oxford were labelled "Clarendon Press" books. This labelling ceased in the 1970s, when the London office of OUP closed. Today, OUP reserves "Clarendon Press" as an imprint for Oxford publications of particular academic importance.[86]

Important series and titles[]

Dictionaries[]

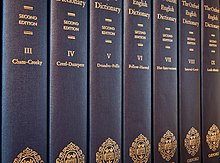

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- Compact Oxford English Dictionary

- Compact Editions of the Oxford English Dictionary

- Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English

- Concise Oxford English Dictionary

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

Bibliographies[]

Indology[]

Classics[]

- Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis, also known as the Oxford Classical Texts

Literature[]

- Oxford World's Classics

- Oxford English Drama

- Oxford English Novels

- Oxford Authors

History[]

- Oxford History of Art

- Oxford History of England

- New Oxford History of England

- Oxford History of the United States

- The Oxford History of the British Empire

- The Oxford History of South Africa

- The Short Oxford History of the Modern World

- Oxford History of Wales

- The Oxford History of Early Modern Europe

- The Oxford History of Modern Europe

- Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History

- Oxford Historical Monographs series

English language teaching[]

- Headway

- Streamline

- English File

- English Plus

- Everybody Up

- Let's Go

- Potato Pals

- Read with Biff, Chip & Kipper

English language tests[]

- Oxford Test of English

- Oxford Placement Test

- Oxford Placement Test for Young Learners

Online teaching[]

- My Oxford English

Bibles[]

Atlases[]

- Atlas of the World Deluxe

- Atlas of the World

- New Concise World Atlas

- Essential World Atlas

- Pocket World Atlas

Music[]

- Carols for Choirs

- Oxford Book of Carols

- The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

- The Oxford Companion to Music

- Oxford Book of English Madrigals

- Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems

- Oxford History of Western Music

Scholarly journals[]

OUP as Oxford Journals has also been a major publisher of academic journals, both in the sciences and the humanities; as of 2016 it publishes over 200 journals on behalf of learned societies around the world.[88] It has been noted as one of the first university presses to publish an open access journal (Nucleic Acids Research), and probably the first to introduce Hybrid open access journals, offering "optional open access" to authors to allow all readers online access to their paper without charge.[89] The "Oxford Open" model applies to the majority of their journals.[90] The OUP is a member of the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association.[citation needed]

Clarendon Scholarships[]

Since 2001, Oxford University Press has financially supported the Clarendon bursary, a University of Oxford graduate scholarship scheme.[91]

See also[]

- Category:Oxford University Press academic journals

- List of Oxford University Press journals

- Hachette

- Hart's Rules for Compositors and Readers at the University Press, Oxford

- List of largest UK book publishers

- Cambridge University Press v. Patton, a copyright infringement suit in which OUP is a plaintiff

- Blackstone Press

- Harvard University Press

- University of Chicago Press

- Edinburgh University Press

- Express Publishing

- Blavatnik School of Government (opened in 2015), opposite the OUP on Walton Street

Notes[]

- ^ Under various commissions chaired by Hadow.

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Balter, Michael (16 February 1994). "400 Years Later, Oxford Press Thrives". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ "About Oxford University Press". OUP Academic. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Press". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Carter p. 137

- ^ Carter, passim

- ^ Peter Sutcliffe, The Oxford University Press: an informal history (Oxford 1975; re-issued with corrections 2002) pp. 53, 96–97, 156.

- ^ Sutcliffe, passim

- ^ "Company Overview of Oxford University Press Ltd". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ Barker p. 4; Carter pp. 7–11.

- ^ Carter pp. 17–22

- ^ Sutcliffe p. xiv

- ^ Carter ch. 3

- ^ Barker p. 11

- ^ Carter pp. 31, 65

- ^ Carter ch. 4

- ^ Carter ch. 5

- ^ Carter pp. 56–58, 122–27

- ^ Barker p. 15

- ^ Helen M. Petter, The Oxford Almanacks (Oxford, 1974)

- ^ Barker p. 22

- ^ Carter p. 63

- ^ Barker p. 24

- ^ Carter ch. 8

- ^ Barker p. 25

- ^ Carter pp. 105–09

- ^ Carter p. 199

- ^ Barker p. 32

- ^ I.G. Phillip, William Blackstone and the Reform of the Oxford University Press (Oxford, 1957) pp. 45–72

- ^ Carter, ch. 21

- ^ Sutcliffe p. xxv

- ^ Barker pp. 36–39, 41. Sutcliffe p. 16

- ^ Barker p. 41. Sutcliffe pp. 4–5

- ^ Sutcliffe, pp. 1–2, 12

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 2–4

- ^ Barker p. 44

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 39–40, 110–111

- ^ Harry Carter, Wolvercote Mill ch. 4 (second edition, Oxford, 1974)

- ^ Jeremy Maas, Holman Hunt and the Light of the World (Scholar Press, 1974)

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 6

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 36

- ^ Barker pp. 45–47

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 19–26

- ^ Sutcliffe pp 14–15

- ^ Barker p. 47

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 27

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 45–46

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 16, 19. 37

- ^ The Clarendonian, 4, no. 32, 1927, p. 47

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 48–53

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 89–91

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 64

- ^ Barker p. 48

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 53–58

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 56–57

- ^ Simon Winchester, The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford, 2003)

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 98–107

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 66

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 109

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 141–48

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 117, 140–44, 164–68

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 155

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 113–14

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 79

- ^ Sutcliffe pp. 124–28, 182–83

- ^ See chapter two of Rimi B. Chatterjee, Empires of the Mind: A History of the Oxford University Press in India During the Raj (New Delhi: OUP, 2006) for the whole story of Gell's removal.

- ^ Milford's Letterbooks

- ^ Ngugi wa Thiongo, 'Imperialism of Language', in Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedom translated from the Gikuyu by Wangui wa Goro and Ngugi wa Thiong'o (London: Currey, 1993), p. 34.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 870. ISBN 0300055366.

- ^ For an account of the Sacred Books of the East and their handling by OUP, see chapter 7 of Rimi B. Chatterjee's Empires of the Mind: a history of the Oxford University Press in India during the Raj; New Delhi: OUP, 2006

- ^ Rimi B. Chatterjee, 'Canon Without Consensus: Rabindranath Tagore and the "Oxford Book of Bengali Verse"'. Book History 4: 303–33.

- ^ See Rimi B. Chatterjee, 'Pirates and Philanthropists: British Publishers and Copyright in India, 1880–1935'. In Print Areas 2: Book History in India edited by Swapan Kumar Chakravorty and Abhijit Gupta (New Delhi: Permanent Black, forthcoming in 2007)

- ^ See Simon Nowell-Smith, International Copyright Law and the Publisher in the Reign of Queen Victoria: The Lyell Lectures, University of Oxford, 1965–66 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968).

- ^ Beachey, RW (1976). "The East Africa ivory trade in the nineteenth century". The Journal of African History. 8 (2): 269–290. doi:10.1017/S0021853700007052.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sutcliffe p. 210

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hinnells p. 6

- ^ Oxford p. 4

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 211

- ^ Jump up to: a b Oxford p. 6

- ^ Hinnells p. 8

- ^ Hinnells pp. 18–19; OUP joined in 1936.

- ^ Sutcliffe p. 168

- ^ Hinnells p. 17

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sutcliffe p. 212

- ^ Hinnells p. 34

- ^ Flood, Alison (9 June 2021). "Oxford University Press to end centuries of tradition by closing its printing arm". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Oxford University Press website, Archives

- ^ "About". Oxfordbibliographies.com.

- ^ "Oxford Journals". OUP. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Optional Open Access Experiment". Journal of Experimental Botany. Oxford Journals. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Oxford Open". Oxford Journals. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "History of the Clarendon Fund". University of Oxford. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

Sources[]

- Barker, Nicolas (1978). The Oxford University Press and the Spread of Learning. Oxford.

- Carter, Harry Graham (1975). A History of the Oxford University Press. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 955872307.

- Chatterjee, Rimi B. (2006). Empires of the Mind: A History of the Oxford University Press in India During the Raj. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195674743.

- Hinnells, Duncan (1998). An Extraordinary Performance: Hubert Foss and the Early Years of Music Publishing at the Oxford University Press. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-323200-6.

- Oxford Music: The First Fifty Years '23−'73. London: Oxford University Press Music Department. 1973.

- Sutcliffe, Peter (1978). The Oxford University Press: An Informal History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-951084-9.

- Sutcliffe, Peter (1972). An Informal History of the OUP. Oxford: OUP.

Further reading[]

- Gadd, Ian, ed. (2014). The History of Oxford University Press: Volume I: Beginnings to 1780. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 9780199557318.

- Eliot, Simon, ed. (2014). The History of Oxford University Press: Volume II: 1780 to 1896. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 9780199543151.

- Louis, Wm. Roger, ed. (2014). The History of Oxford University Press: Volume III: 1896 to 1970. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 9780199568406. Also online doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199568406.001.0001.

- Robbins, Keith, ed. (2017). The History of Oxford University Press: Volume IV: 1970 to 2004. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 9780199574797.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original works published by or about: Oxford University Press |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oxford University Press. |

- Official website

- Oxford University Press at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Illustrated article: The Most Famous Press in the World, , June 1903

- Oxford University Press

- 1586 establishments in England

- 1896 establishments in New York (state)

- Book publishing companies of England

- Book publishing companies based in New York (state)

- University presses of the United Kingdom

- Departments of the University of Oxford

- Sheet music publishing companies

- Shops in Oxford

- Museums in Oxford

- Literary museums in England

- Publishing companies established in the 16th century

- Organizations established in the 1580s

- Companies based in Oxford

- Reference publishers

- Academic publishing companies