PNC Park

| |

PNC Park in 2016 | |

PNC Park Location near Downtown Pittsburgh | |

| Address | 115 Federal Street |

|---|---|

| Location | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 40°26′49″N 80°0′21″W / 40.44694°N 80.00583°WCoordinates: 40°26′49″N 80°0′21″W / 40.44694°N 80.00583°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Sports & Exhibition Authority of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County[1] |

| Operator | Pittsburgh Pirates[1] |

| Capacity | 37,898 (2001–2003) 38,496 (2004–2007) 38,362 (2008–2017) 38,747 (2018–present)[2] |

| Record attendance | 40,889 (October 7, 2015) |

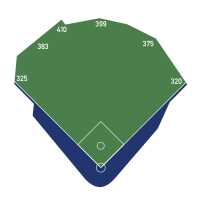

| Field size | Left Field – 325 feet (99 m) Left-Center – 383 feet (117 m) Deep Left-Center Field – 410 feet (125 m) Center Field – 399 feet (122 m) Right-Center – 375 feet (114 m) Right Field – 320 feet (98 m) Backstop – 51 feet (16 m)  |

| Surface | Kentucky Bluegrass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | April 7, 1999 |

| Opened | March 31, 2001 |

| Construction cost | US$216 million ($316 million in 2020 dollars[3]) |

| Architect | HOK Sport (now Populous)[4] L.D. Astorino & Associates |

| Project manager | Project Management Consultants LLC[5] |

| Structural engineer | Thornton-Tomasetti Group Inc.[6] |

| Services engineer | M*E Engineers[6] GAI Consultants, Inc. |

| General contractor | Dick Corporation/Barton Malow JV[7] |

| Tenants | |

| Pittsburgh Pirates (MLB) (2001–present) | |

PNC Park is a Major League Baseball stadium located on the North Shore of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It is the fifth home of the Pittsburgh Pirates.[8][9] It was opened during the 2001 MLB season, after the controlled implosion of the Pirates' previous home, Three Rivers Stadium. PNC Park stands just east of its predecessor along the Allegheny River with a view of the Downtown Pittsburgh skyline. Constructed of steel and limestone, PNC Park features a natural grass playing surface and has a seating capacity of 38,747 people for baseball.

Plans to build a new stadium for the Pirates originated in 1991 but did not come to fruition for five years. Funded in conjunction with Heinz Field and the David L. Lawrence Convention Center, the park was constructed for $216 million over 24 months, faster than most modern stadiums. Built in the "retro-classic" style modeled after past venues like Pittsburgh's Forbes Field, PNC Park also introduced unique features, such as the use of limestone in the building's facade.[8] The park also features a riverside concourse, steel truss work, an extensive out-of-town scoreboard, and local eateries. Several tributes to former Pirate Roberto Clemente were incorporated into the ballpark, which included renaming the Sixth Street Bridge behind it in his honor. In addition to the Pirates' regular season and postseason home games, PNC Park has hosted other sporting events, including the 2006 Major League Baseball All-Star Game and numerous concerts.

PNC Financial Services originally purchased the naming rights in 1998 for $30 million over 20 years.[10][11] Their current naming rights agreement runs through 2031.[12]

PNC Park is widely considered one of the best ballparks in America because of its location, views of the Pittsburgh skyline and Allegheny River, timeless design, and clear angles of the field from every seat.[13][14][15][16]

History[]

Planning and funding[]

On September 5, 1991, Pittsburgh mayor Sophie Masloff proposed a new 44,000-seat stadium for the Pittsburgh Pirates on the city's North Side.[17] Three Rivers Stadium, the Pirates' and Steelers' home at the time, had been designed for functionality rather than "architecture and aesthetics".[17] The location of Three Rivers Stadium came to be criticized for being in a hard-to-access portion of the city, where traffic congestion occurred before and after games.[18] Discussions about a new ballpark took place, but were never seriously considered until entrepreneur Kevin McClatchy purchased the team in February 1996. Until McClatchy's purchase, plans about the team remaining in Pittsburgh were uncertain.[17] In 1996, Masloff's successor, Tom Murphy, created the "Forbes Field II Task Force". Made up of 29 political and business leaders, the team studied the challenges of constructing a new ballpark. Their final report, published on June 26, 1996, evaluated 13 possible locations. The "North Side site" was recommended due to its affordable cost, potential to develop the surrounding area, and opportunity to incorporate the city skyline into the stadium's design.[17] The site selected for the ballpark is just upriver from the site of early Pirates home field Exposition Park.[19][20]

After a political debate, public money was used to fund PNC Park. Originally, a sales tax increase was proposed to fund three projects: PNC Park, Heinz Field (the Steelers' current home), and an expansion of the David L. Lawrence Convention Center. However, after the proposal was soundly rejected in a 1997 referendum known as the , the city developed Plan B.[21] Similarly controversial, the alternative proposal was labeled Scam B by opponents.[22] Some members of the Allegheny Regional Asset District felt that the Pirates' pledge of $40 million toward the new stadium was too little, while others criticized the amount of public money allocated for Plan B. One member of the Allegheny Regional Asset District board called the use of tax dollars "corporate welfare".[23][24] The plan, totaling $809 million, was approved by the Allegheny Regional Asset District board on July 9, 1998—with $228 million allotted for PNC Park.[23][25] Shortly after Plan B was approved, the Pirates made a deal with Pittsburgh city officials to remain in the city until at least 2031.[22]

There was popular sentiment by fans for the Pirates to name the stadium after former outfielder Roberto Clemente. However, locally based PNC Financial Services purchased the stadium's naming rights in August 1998.[10][26] As per the agreement, PNC Bank will pay the Pirates approximately $2 million each year through 2020, and also has a full-service PNC branch at the stadium.[27][28] The total cost of PNC Park was $216 million.[8][9] Shortly after the naming rights deal was announced, the city of Pittsburgh renamed the 6th Street Bridge near the southeast corner of the site of the park the Roberto Clemente Bridge as a compromise to fans who had wanted the park named after Clemente.[29]

Design and construction[]

Kansas City-based Populous (then HOK Sport), which designed many other major league ballparks of the late 20th and early 21st century, designed the ballpark.[30][31] The design and construction management team consisted of the Dick Corporation and Barton Malow.[8] An effort was made in the design of PNC Park to salute other "classic style" ballparks, such as Fenway Park, Wrigley Field, and Pittsburgh's Forbes Field; the design of the ballpark's archways, steel truss work, and light standards are results of this goal.[8][32] PNC Park was the first two-deck ballpark to be built in the United States since Milwaukee County Stadium opened in 1953.[9][32] The park features a 24 by 42 foot (7.3 by 12.8 m) Sony JumboTron, which is accompanied by the first-ever LED video boards in an outdoor MLB stadium.[33] PNC Park is the first stadium to feature an out-of-town scoreboard with the score, inning, number of outs, and base runners for every other game being played around the league.[33]

Ground was broken for PNC Park on April 7, 1999,[34] after a ceremony to christen the newly renamed Roberto Clemente Bridge.[35] As part of original plans to create an enjoyable experience for fans, the bridge is closed to vehicular traffic on game days to allow spectators to park in Pittsburgh's Golden Triangle and walk across the bridge to the stadium.[36][37] PNC Park was built with Kasota limestone shipped from a Minnesota river valley, to contrast the brick bases of other modern stadiums.[38] The American-made raw steel for the ballpark was fabricated in Brownsville, Pennsylvania by Wilhelm and Krus.[39] The stadium was constructed over a 24-month span—at the time of construction, three months faster than any other modern major league ballpark—and the Pirates played their first game less than two years after groundbreaking.[40] The quick construction was accomplished with the use of special computers, which relayed building plans to builders 24 hours per day.[40] In addition, all 23 labor unions involved in the construction signed a pact that they would not strike during the building process.[40] As a result of union involvement and attention to safety regulations, the construction manager, the Dick Corporation, received a merit award for its safety practices from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.[41]

Statues of Pirates' Hall of Famers Honus Wagner, Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell and Bill Mazeroski are positioned at various points outside of PNC Park. Wagner and Clemente's statues were previously located outside of Three Rivers Stadium, and after the venue was imploded, the two statues were removed from their locations, refurbished, and relocated outside PNC Park.[42] Wagner's statue was originally unveiled at Forbes Field in 1955.[43][44] The base of Clemente's statue is shaped like a baseball diamond, with dirt from three of the fields Clemente played at—Santurce Field in Carolina, Puerto Rico, Forbes Field, and Three Rivers Stadium—at each base.[45] On October 1, 2000, after the final game at Three Rivers Stadium, Stargell threw out the ceremonial last pitch. He was presented with a model of a statue that was to be erected in his honor outside of PNC Park.[46] The statue was officially unveiled on April 7, 2001; however, Stargell did not attend due to health problems and died of a stroke two days later.[47][48] A statue for Bill Mazeroski was added at the right field entrance, at the south end of Mazeroski Way, during the 2010 season. This was the 50th anniversary of the Pirates' 1960 World Series championship, which Mazeroski clinched with a Game 7 walk-off home run at Forbes Field. The statue itself was designed based on that event.[49]

Opening and reception[]

The Pirates opened PNC Park with two exhibition games against the New York Mets—the first of which was played on March 31, 2001.[50] The first official baseball game played in PNC Park was between the Cincinnati Reds and the Pirates, on April 9, 2001. The Reds won the game by the final score of 8–2.[51] The first pitch—a ball—was thrown from Pittsburgh's Todd Ritchie to Barry Larkin. In the top of the first inning, Pittsburgh native Sean Casey's two-run home run was the first hit in the park. The first Pirates' batter, Adrian Brown, struck out; however, later in the inning Jason Kendall singled—the first hit by a Pirate in their new stadium.[8]

PNC Park had an average attendance of 30,742 people per game throughout its inaugural season,[52] though it would drop approximately 27% the following season to 22,594 spectators per game.[53] Throughout the 2001 season, businesses in downtown and on the Northside of Pittsburgh showed a 20–25% increase in business on Pirate game days.[54]

Pirates' vice-president Steve Greenberg said, "We said when construction began that we would build the best ballpark in baseball, and we believe we've done that."[55] Major League Baseball executive Paul Beeston said the park was "the best he's seen so far in baseball".[55] Many of the workers who built the park said that it was the nicest that they had seen.[41] Jason Kendall, Pittsburgh's catcher at the opening of the park, called PNC Park "the most beautiful ballpark in the game".[56] Different elements of PNC Park were used in the design of New York's Citi Field.[57]

Upon opening in 2001, PNC Park was praised by fans and media alike. ESPN.com writer Jim Caple ranked PNC Park as the best stadium in Major League Baseball, with a score of 95 out of 100.[58] Caple compared the park to Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater, calling the stadium itself "perfect", and citing high ticket prices as the only negative aspect of visiting the park.[58] Jay Ahjua, author of Fields of Dreams: A Guide to Visiting and Enjoying All 30 Major League Ballparks, called PNC Park one of the "top ten places to watch the game".[59] Eric Enders, author of Ballparks Then and Now and co-author of Big League Ballparks: The Complete Illustrated History, said it was "everything a baseball stadium could hope to be" and "an immediate contender for the title of best baseball park ever built".[60] In 2008, Men's Fitness named the park one of "10 big league parks worth seeing this summer".[61][62] A 2010 unranked list of "America's 7 Best Ballparks" published by ABC News noted that PNC Park "combines the best features of yesterday's ballparks—rhythmic archways, steel trusswork and a natural grass playing field—with the latest in fan and player amenities and comfort".[63] In 2017, a panel of Washington Post sports writers ranked it the 2nd-best stadium in MLB.[14] A 2018 article in Parade dubbed PNC Park "The Jewel of the Allegheny".[64]

Alterations[]

An exhibit honoring Pittsburgh's Negro league baseball teams was introduced in 2006. Located by the stadium's left-field entrance, the display features statues of seven players who competed for the city's Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, including Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige. The exhibit also includes the Legacy Theatre, a 25-seat facility that plays a film about Pittsburgh's history with the Negro leagues.[65] The Pirates donated the statues to the Josh Gibson Foundation in 2015.

In 2007, Allegheny County passed a ban on smoking in most public places, thus making PNC Park completely smoke-free.[66] Before the 2008 season, the Pirates made multiple alterations to PNC Park.[67] The biggest change was removing the Outback Steakhouse located in the left field stands, and adding a new restaurant known as The Hall of Fame Club.[68] Unlike its predecessor, The Hall of Fame Club is open to all ticket-holders on game days;[68] it includes an outdoor patio with a bar and seats with a view of the field.[69] The Pirates feature bands in The Hall of Fame Club after the completion of select games—the first performance was by Joe Grushecky and the Houserockers.[67] The Pirates also announced a program to make the park more environmentally friendly, by integrating "greening initiatives, sustainable business practices and educational outreach".[70] In addition, club and suite sections were outfitted with new televisions.[68]

In 2012, the "Budweiser Bow Tie," a 5,000 square foot (460 m2) bar and lounge located in the right-field corner of the ballpark, was added. The section includes ticketed seats along with areas for groups and the general public. This addition was expected to cost about $1 million. For the 2015 season, many additions to the park took place for a better fan experience. One of the additions to the park is the left-field terrace. It has two levels for standing room, with 250 feet (76 m) of drink rails. The terrace fills the gap between the left-field bleachers and the Rivertowne Brewing Hall of Fame Club and is open to any fan with a ticket. Another addition includes a new outdoor patio that overlooks the center field, right next to the terraces. The patio is now known as "The Porch." The Porch features bar tables and outdoor sofa-style seating and accommodates groups of 25 people. Among the other additions for the 2015 season are: The Corner, which is a full-service bar at the very base of the left-field rotunda with nine flat-screen TVs; Terrace Bar, which is a fully operating bar for fans in the upper concourse; and Pirates Outfitters, an additional merchandise shop located next to the home-plate entrance. The Pirates paid all costs for the additions to the park.[71]

Notable events[]

Baseball[]

PNC Park hosted the 77th Major League Baseball All-Star Game on July 11, 2006.[72] The American League defeated the National League 3–2, with 38,904 spectators in attendance.[73] The first All-Star Game in PNC Park, it was the 5th All-Star Game hosted in Pittsburgh, and the first since 1994.[74] During the game, late Pirate Roberto Clemente was honored with the Commissioner's Historic Achievement Award; his wife, Vera, accepted on his behalf.[75] The stadium hosted the Home Run Derby the previous evening; Ryan Howard, of the Philadelphia Phillies, won the title.[76] During the Derby, Howard and David Ortiz hit home runs into the Allegheny River.[77]

On September 28, 2012, PNC Park saw its first no-hitter when Reds pitcher Homer Bailey no-hit the Pirates, 1–0. PNC Park has yet to see a no-hitter or perfect game thrown by a Pirate.

On October 1, 2013, the Pirates hosted the Cincinnati Reds in the 2013 National League Wild Card Game. This marked the first time a playoff game was played at PNC Park. The Pirates won 6–2, their first postseason victory since 1992, in front of a record crowd of 40,629. The 2014 and 2015 National League Wild Card games were also played at PNC Park.

On July 20, 2020, it was reported that the Pirates were exploring offering use of PNC Park as a temporary home stadium for the Toronto Blue Jays for the 2020 MLB season, as the team was unable to obtain clearance from the Canadian government to play at Rogers Centre under travel restrictions issued because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The team's current GM Ben Cherington previously worked for the Blue Jays before being hired by the Pirates.[78][79] On July 22, 2020, the Toronto Blue Jays were denied permission to play home games at PNC Park by the Pennsylvania Department of Health Secretary Dr. Rachel Levine and Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf.[80]

College baseball[]

The first collegiate baseball game at PNC Park was played on May 6, 2003, between the Pitt Panthers and the Duquesne Dukes, a rivalry that was referred to as the City Game.[81] Duquesne won 2–1.[82] However, due to Duquesne's decision to disband their baseball program following the 2010 season, the series between the two schools came to an end.[83] The PNC Park City Game series ended in Pitt's favor, four games to two, with the 2007 game canceled because of poor field conditions.[84][85][86]

Concerts[]

PNC Park has also hosted various concerts, including Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, Jason Aldean, Billy Joel, The Rolling Stones, Pearl Jam, Jimmy Buffett, Me First and the Gimme Gimmes, Dave Matthews Band, Ed Sheeran and Zac Brown Band.

In film[]

The park also served as a location for the films She's Out of My League (2010), Abduction (2011), Jack Reacher (2012) and Sweet Girl (2021).

Other events[]

PNC Park has hosted various evacuation and response drills, which would be used in the event of a terrorist attack. Members of the United States Department of Homeland Security laid out the groundwork for the initial drill in February 2004.[87] In May 2005, 5,000 volunteers participated in the $1 million evacuation drill, which included mock explosions.[88] A goal of the drill was to test the response of 49 western Pennsylvania emergency agencies.[89] In April 2006, the Department of Homeland Security worked in conjunction with the United States Coast Guard to develop a plan of response for the 2006 All-Star Game.[90] Similar exercises were conducted on the Allegheny River in 2007.[91]

Special features[]

Playing surface and dimensions[]

The playing surface of PNC Park is Tuckahoe Bluegrass, which is a mixture of various types of Kentucky Bluegrass.[92] Installed before the 2009 season, the grass surface was selected for its "high-quality pedigree that is ideal for Northern cities such as Pittsburgh".[92] The infield dirt is a mixture known as "Dura Edge Custom Pro Infield Mix" and was designed solely for PNC Park.[92] The 18-foot (5.5 m) warning track is crushed lava rock.[92][93] The drainage system underneath the field is capable of handling 14 inches (36 cm) of rain per hour.[94] The original playing surface consisted of sand-based natural grass,[95] and was replaced before the 2006 season.[92] The playing surface also underwent a significant renovation following the 2016 season. The 2016 renovation included excavation of the top 3 inches (7.6 cm) of rootzone soil, importing of rootzone material with improved physical properties, deep tillage, laser grading, and installation of new Kentucky bluegrass sod. The infield skin was also excavated to a depth of 4 inches (10 cm) and replaced with new Dura Edge infield mix. Unlike most ballparks, PNC Park's home dugout is located along the third base line instead of the first base line; giving the home team a view of the city skyline.[96] The outfield fence ranges from a height of 6 feet (2 m) in left field to 10 feet (3 m) in center field and 21 feet (6 m) in right field, a tribute to former Pirate right fielder Roberto Clemente, who wore number 21.[61][97] The distance from home plate to the outfield fence ranges from 320 feet (98 m) in right field to 410 feet (125 m) in left center; the straightaway center field fence is set at 399 feet (122 m).[8] At its closest point, the Allegheny River is 443 ft 4 in (135.128 m) from the plate.[8][9] On July 6, 2002, Daryle Ward became the first player to hit the river "on the fly". On June 2, 2013, Garrett Jones became only the second player to accomplish the feat, and was the first Pirate to do so.[98] On May 19, 2015, Pirates first baseman Pedro Alvarez became the third person to do this, although the ball actually landed in a boat on the river rather than in the water.[99] Within a two-week period (May 8 & May 22, 2019), Pirates first baseman Josh Bell splashed the fourth and fifth home runs directly into the Allegheny River; the first one is estimated to have traveled better than 470 feet (143 m), while the second traveled more than 450 feet (137 m). The longest home run in PNC Park history was 484 feet (148 m) hit to left-center field by Sammy Sosa on April 12, 2002.[100]

Seating, attendance, and ticket prices[]

During its opening season, PNC Park's seating capacity of 38,496 was the second-smallest of any major league stadium (the smallest being Fenway Park).[8][101] Seats are angled toward the field and aisles are lowered to give spectators improved views of the field.[102] The majority of the seats (26,000) are on the first level,[55] and the highest seat in the stadium is 88 feet (27 m) above the playing surface.[103] At 51 feet (16 m), the batter is closer to the seats behind home plate than to the pitcher.[104] At their closest point, seating along the baselines is 45 feet (14 m) from the bases.[102] The four-level steel rotunda and a section above the out-of-town scoreboard offer standing-room-only space.[105] With the exception of the bleacher sections, all seats in the park offer a view of Pittsburgh's skyline.[106]

In its opening season, PNC Park's tickets were priced between $9 and $35 for general admission.[55][107] One of only two teams not to increase ticket prices entering the 2009 season, PNC Park ranked as having the third-cheapest average ticket prices in the league in 2009.[108] Despite price increases in the 2015 season, the average ticket price at PNC Park remained in the bottom five among MLB teams.[109] The stadium's average ticket price held between $15 and $17 from 2006 to 2013 (among the lowest in Major League Baseball), then rose to $18.32 in 2014, $19.99 in 2015, and $29.96 in 2016.[110]

In the stadium's first decade, average attendance dipped under 20,000 fans per game four times.[111] Before 2013, the Pirates had only one winning record since 1992.[112] Through 2004, 5% of games played at PNC Park were sold out.[102] The number of sellouts increased in 2012 and 2013; after filling PNC Park 17 times in 2012, the team played to capacity crowds at 23 games in 2013.[113] In 2014, average attendance crossed the 30,000 mark for the first time since PNC Park's inaugural season in 2001, and remained above 30,000 in 2015 before dropping to 27,000 in 2016.[111]

Eateries[]

The main eating concourse, known as "Tastes of Pittsburgh",[106] features a wide range of options including traditional ballpark foods, hometown specialties, and more exotic fare like sushi.[114] Pittsburgh's hometown specialties include Primanti Brothers sandwiches, whose signature item consists of meat, cheese, hand-cut French fries, tomatoes, and coleslaw between two slices of Italian bread.[115][116] Other local eateries offered include Mrs. T's Pierogies, Quaker Steak & Lube, Augustine's Pizza, and Benkovitz Seafood.[114] Located behind center field seating is Manny's BBQ, which offers various barbecue meals. It is named for former Pirates' catcher Manny Sanguillén, who has been known to sign autographs for fans waiting in line.[101][117] For the 2008 season, the Pirates created an all-you-can-eat section in the right field corner.[67] Fans seated in the section are allowed "unlimited hot dogs, hamburgers, nachos, salads, popcorn, peanuts, ice cream and pop" for an entire game.[118] In addition to the food offered, fans are free to bring their own food into the stadium, a rarity among the league's ballparks.[97]

For its first 13 years, PNC Park sold Pepsi products, a contrast from its predecessor Three Rivers Stadium, which sold Coca-Cola products, as well as Heinz Field and Mellon Arena. In right field, several versions of the Pepsi Globe as well as a Pepsi bottle were displayed on large posts behind the stands and lit up every time the Pirates hit a home run. In 2014, the Pirates switched to Coca-Cola.[119] The Pepsi signage in right field was converted into advertising for locally based health insurance company Highmark.[120]

In 2016, PNC Park made news with their introduction of the "Cracker Jack & Mac Dog". The foot-long all-beef hot dog was topped with macaroni and cheese, salted caramel sauce, deep-fried pickled jalapenos and a side of caramel-covered popcorn.[121] Instead of a bun, naan bread was used to hold everything together.[122]

Contractors[]

As with its predecessor, PNC Park's concessions service provider is Aramark,[123][124] while the premium seating areas (The Lexus Club, PBC Level and Suites Level) are serviced by Levy Restaurants.[125] In March 2019, The Lexus Club was replaced by the Hyundai Club. Food service will be handled by Aramark of Philadelphia. The partnership ran through the 2021 season.[126]

Transportation access[]

PNC Park is located at exit 1B of Interstate 279 and within 1 mile (1.6 km) of both Interstate 376 and Interstate 579. The park is also served by the North Side transit station of the Pittsburgh subway system.

Climate[]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[]

Footnotes

- ^ a b "History". www.pgh-sea.com. Sports & Exhibition Authority of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. September 1, 2009. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ Trdinich, Jim (March 13, 2018). 2018 Pittsburgh Pirates Media Guide [PNC Park Information]. Major League Baseball Advanced Media. p. 241.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Work: Ballparks". Populous. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates PNC Park". Project Management Consultants. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "Architects, Contractors and Subcontractors of Current Big Five Facility Projects". Street & Smith's SportsBusiness Journal. July 24, 2000. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ "PNC Park". Ballparks.com. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "PNC Park". PittsburghPirates.com. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "PNC Park at North Shore". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Jaeger, Lauren (August 17, 1998). "PNC Bank Purchases Naming Rights To Pittsburgh Pirates' New Stadium". Amusement Business. 110 (33): 10.

- ^ Gorman, Kevin (March 4, 2021). "Pirates, PNC agree to 10-year extension of stadium naming rights deal for PNC Park". TribLIVE.com. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates add ten years to PNC Park naming rights deal". SportsPro. March 5, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ PNC Park Voted Best Ballpark In America By Fans

- ^ a b How many ballparks have you visited? (Washington Post)

- ^ How does PNC Park rank in a list of MLB's 'best ball parks'?

- ^ All 30 MLB stadiums, ranked

- ^ a b c d Bouma, Ben (1998). "Heading for Home". On Deck. 3 (3): 42–8.

- ^ Smith, Curt (2001). Storied Stadiums. New York City: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1187-6.

- ^ Potter, Chris (June 12, 2008). "Was There A Baseball Field That the Pittsburgh Pirates Played in Before Forbes Field in Oakland?". Pittsburgh City Paper; You Had To Ask. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "Exposition Park". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 11, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "Plan B". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Dvorchak, Robert (June 21, 1998). "A TD for Plan B". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Barnes, Tom; Dvorchak, Robert (July 10, 1998). "Plan B Approved: Play ball!". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Cook, Ron (June 22, 1998). "Plan B flawed; Option Is Worse". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on December 8, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Barnes, Tom (February 11, 1998). "Arena Won't Be Part of Plan B". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Fried, Gil (2005). Managing Sport Facilities. Human Kinetics. p. 223. ISBN 0-7360-4483-3.

- ^ Wolfley, Bob (February 28, 2008). "Values of venue naming rights can vary widely". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel; Sports. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ "Stadium naming rights". Sports Business. ESPN.com. September 29, 2004. Archived from the original on October 21, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ Clemente Bridge Too Much or Too Little? Ariba’s Popularity Extends From Fans to Collectors Pittsburgh Sports Report September 1998

- ^ Dulac, Gerry (September 28, 1998). "Football Stadium Architect Selected". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "PNC Park". Populous.com. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ a b Plunkett, Jack W. (2006). Plunkett's Sports Industry Almanac 2007: Sports Industry Market Research. Plunkett Research Ltd. pp. Pittsburgh Pirates. ISBN 1-59392-073-3.

- ^ a b Bouchette, Ed (April 15, 2001). "Technology Park". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- ^ Barnes, Tom (April 8, 1999). "City, Pirates Break Ground for PNC Park With Big Civic Party". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ Pro, Johnna A. (April 8, 1999). "Clemente's Family Helps to Christen Renamed Bridge". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; Local News. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ Scarpaci, Joseph L.; Kevin Joseph Patrick (2006). Pittsburgh and the Appalachians: Cultural and Natural Resources in a Postindustrial Age. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-8229-4282-8.

- ^ Castiglione, Joe; Lyons, Douglas B. (2004). Broadcast Rites and Sites: I Saw It on the Radio with the Boston Red Sox. Taylor Trade Publications. p. 223. ISBN 1-58979-081-2.

PNC Park.

- ^ Lowry, Patricia (April 15, 2001). "The New Jewel on the Allegheny Might Be the Best Ballpark". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Here comes the steel for PNC Park

- ^ a b c Dvorchak, Robert (April 15, 2001). "PNC Park: The Political Struggle Over Financing PNC Park Went Into Extra Innings". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ a b McKay, Jim (April 15, 2001). "Workers Proud of What They Have Wrought". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- ^ Barnes, Tom (November 22, 2000). "Sports Bar Planned Outside PNC Park". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ DeValeria & DeValeria 1995, p. 298

- ^ Hittner, Arthur D. (2003). Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball's Flying Dutchman. McFarland. p. 257. ISBN 0-7864-1811-7.

- ^ Ruff, Donna (2006). 60 Hikes Within 60 Miles: Pittsburgh. Menasha Ridge Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-89732-591-5.

- ^ Finoli, Dave (2006). The Pittsburgh Pirates. Arcadia Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 0-7385-4915-0.

- ^ "Stargell's Death Linked to Hypertension". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. April 9, 2001. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Native Casey Paces Reds Over Pirates, 8-2". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. April 9, 2001. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ Kovacevic, Dejan (January 28, 2010). "Mazeroski On Statue Plan: 'Couldn't Believe It'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ Biertempfel, Bob (April 1, 2001). "Pirates Lose First Test Run at PNC Park". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ Smith, Curt (2003). Storied Stadiums: Baseball's History Through Its Ballparks. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 562. ISBN 0-7867-1187-6.

- ^ "MLB Attendance Report - 2001". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ "MLB Attendance Report - 2002". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Brown, Charles (November–December 2001). "Pittsburgh's Putting on its Game Face". Pittsburgh International Airport Magazine. 1 (1): 10–3.

- ^ a b c d "PNC Park Gets Rave Reviews". ThePittsburghChannel.com. February 21, 2001. Archived from the original on March 17, 2005. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ Kendall, Jason (April 1, 2001). "New Ballpark Something to Behold". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ Kovacevic, Dejan (May 9, 2009). "Pirates Notebook: Mets' Stadium Inspired by PNC". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ a b Caple, Jim. "Pittsburgh's Gem Rates the Best". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ Phillips, Oberlin & Pattak 2005, pp. 314–5

- ^ Enders, Eric (2009). Big League Ballparks: The Complete Illustrated History. New York: Metro Books Publishers. p. 512. ISBN 978-1-4351-1452-4.

- ^ a b Pratt, Devin. "Top Stadiums: Pittsburgh's PNC Park". Men's Fitness. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ Langosch, Jenifer (April 2, 2008). "PNC in Men's Fitness Top 10 Stadiums". PittsburghPirates.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ Mayerowitz, Scott (April 2, 2010). "America's 7 Best Ballparks". ABC News. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ PNC Park: The Jewel of the Allegheny (Parade)

- ^ Finder, Chuck (June 27, 2006). "Pirates Put History on Display". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ "PNC Park Becomes Smoke-Free Facility" (Press release). PittsburghPirates.com. March 20, 2007. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c Belko, Mark (April 4, 2008). "Pirates Show Off Park Features". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c Price, Karen (April 4, 2008). "PNC Park features overhauled eatery". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. ProQuest 382404429.

- ^ "PNC Park: General Information". PittsburghPirates.com. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ "Pirates Launch Greening Initiatives Program at PNC Park" (Press release). PittsburghPirates.com. March 11, 2008. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ Belko, Mark (January 31, 2012). "Bud-Branded Lounge Set for PNC Park". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates Host 2006 All-Star Week, Including 77th MLB All-Star Game". MLB.com (Press release). April 28, 2006. Retrieved April 9, 2006.

- ^ Eagle, Ed (July 12, 2006). "Young Rallies AL to Victory". MLB.com. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ "All-Star Results". MLB.com. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Bloom, Barry M. (July 12, 2006). "Baseball Honors Clemente". MLB.com. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ Bloom, Barry M. (July 10, 2006). "Howard Powers Way to Derby Crown". MLB.com. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ Briggs, David (July 10, 2006). "Pirates of the Allegheny". MLB.com. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- ^ "Blue Jays exploring possibility of playing games at PNC Park". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Jays have looked into Pittsburgh's PNC Park as home games site". Sportsnet. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Toronto Blue Jays denied permission to play in Pittsburgh's PNC Park for 2020 MLB season". CBSSports.com. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Baseball Falls to Duquesne, 2-1, at PNC Park". PittsburghPanthers.com. May 6, 2003. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ Fittipaldo, Ray (May 7, 2003). "Pitcher's Big-League Effort Lifts Duquesne Past Pitt, 2-1". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; Duquesne/Atlantic 10. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ^ Dunlap, Colin (May 17, 2010). "Duquesne's Baseball Team Plays (and Loses) in Its Final Appearance at Home". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Axelrod, Phil (April 17, 2008). "Baseball: Three Freshmen Step Up as Panthers Rout Dukes". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ Axelrod, Phil (April 15, 2005). "Baseball: Pitt, Duquesne to Treat Game Like Exhibition". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ "Panthers Fall to Duquesne, 5-2 at PNC Park". PittsburghPanthers.com. May 6, 2005. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ "Terrorism Drill Scheduled For PNC Park". Pittsburgh News. WTAE-TV. February 25, 2004. Archived from the original on December 21, 2004. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Roberts, Josie (May 4, 2005). "Goodie Bags, Entertainment Part of PNC Park Drill". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ May, Glenn; Heinrichs, Allison M. (May 8, 2005). "Drills and Thrills 5,000 Volunteers Go to Bat as Victims of Mock Disaster". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

- ^ "Coast Grd. To Keep Rivers Safe During All-Star Gm". KDKA-TV. April 14, 2006. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ "Terror Drill on Allegheny River Today". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. September 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "PNC Park Surface Getting Full Makeover". PittsburghPirates.com. October 14, 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ^ Langosch, Jenifer (April 6, 2009). "Pirates Show Off Revamped PNC Park". PittsburghPirates.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ Cagan, Jonathan; Craig M. Vogel (2002). Creating Breakthrough Products: Innovation from Product Planning to Program. FT Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-13-969694-6.

- ^ "Sod Installed At PNC Park". ThePittsburghChannel.com. October 30, 2000. Archived from the original on March 17, 2005. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ Pahigian & O'Connell 2004, p. 228

- ^ a b Ahuja 2001, p. 68

- ^ Corcoran, Cliff (June 3, 2013). "Watch: Garrett Jones goes where no Pirate has gone before with splash HR at PNC Park". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Pedro Alvarez hits home run into a boat on the Allegheny River". sports.yahoo.com. May 20, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Reuter, Joel. "The Longest 'Moon Shot' Home Run in the History of Each MLB Stadium".

- ^ a b Warner, Gary A. (May 10, 2005). "Boutique Ballparks // Three Quirky New Baseball Stadiums Replace Indistinguishable 'Concrete Doughnuts'". The Orange County Register. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Pahigian & O'Connell 2004, p. 218

- ^ Phillips, Oberlin & Pattak 2005, p. 314

- ^ "New Ballpark Comparisons". New Ballpark. MinnesotaTwins.com. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Pahigian & O'Connell 2004, pp. 220–1

- ^ a b Ahuja 2001, p. 67

- ^ Finder, Chuck (October 12, 2000). "Pirates Unveil Ticket Prices". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Krise, Todd (June 12, 2008). "PNC Park a Big League Bargain". MLB.com. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Pirates' average ticket price fourth-lowest in Major League Baseball

- ^ Pittsburgh Pirates average ticket price from 2006 to 2016 (in U.S. dollars)

- ^ a b "Pittsburgh Pirates Attendance, Stadiums, and Park Factors". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ Schiavenza, Matt (September 11, 2013). "How Life Got Good Again for the Pittsburgh Pirates". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ "Pirates Release 2014 Season Ticket Pricing". PittsburghPirates.com. September 27, 2013. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Jones, Diana Nelson (April 15, 2001). "Buy Me Some Peanuts and Uh, Sushi?". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ^ Kadushin, Raphael; McLain, David (August 2003). "15222: Come Hungry". National Geographic Magazine: 114–22. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ Bradish, Kelly (December 19, 2002). "The Primanti's Tradition". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ Meehan, Peter (June 8, 2008). "Finding the Hits, Avoiding the Errors". The New York Times; Travel. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ Batz Jr., Bob (April 3, 2008). "At PNC Park, 'All-You-Can-Eat' Seats". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ "Pirates to Switch Soft Drinks in 2014". KDKA-TV. March 8, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ Schmitz, Jon (March 28, 2014). "It may take extra innings to finish PNC Park's Closer". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ McKay, Gretchen. "PNC Park takes crazy foods to new level with Cracker Jack & Mac Dog". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Petroff, Alanna (December 22, 2016). "The weirdest fast food of 2016". CNNMoney. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "Aramark to Feature Local Favorites From Around the League During Mid-Summer Classic". Aramark. May 27, 2006. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ "Food Services". Major League Partners. Aramark. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ "PNC Park". Levy Restaurants. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ "Changes at PNC Park". Pittsburgh Business Times. March 26, 2019.

- ^ "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

Bibliography

- Ahuja, Jay (2001). Fields of Dreams: A Guide to Visiting and Enjoying All 30 Major League Ballparks. Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-2193-7.

- DeValeria, Dennis; DeValeria, Jeanne Burke (1995). Honus Wagner: A Biography. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-5665-9.

- Pahigian, Josh; O'Connell, Kevin (2004). The Ultimate Baseball Road-trip: A Fan's Guide to Major League Stadiums. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-59228-159-1.

- Phillips, Jenn; Oberlin, Loriann Hoff; Pattak, Evan M. (2005). Insiders' Guide to Pittsburgh. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-3507-5.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to PNC Park. |

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Three Rivers Stadium

|

Home of the Pittsburgh Pirates 2001 – present |

Succeeded by Current

|

| Preceded by | Host of the MLB All-Star Game 2006 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of the National League Wild Card Game 2013 2014 2015 |

Succeeded by Citi Field

|

- Sports venues completed in 2001

- Major League Baseball venues

- Sports venues in Pittsburgh

- Pittsburgh Pirates stadiums

- Baseball venues in Pennsylvania

- Populous (company) buildings