Pandora's Box (1929 film)

| Pandora's Box | |

|---|---|

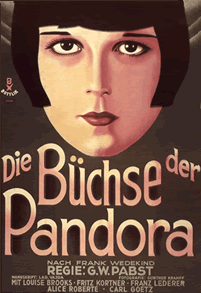

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | G. W. Pabst |

| Written by | G.W. Pabst Ladislaus Vajda |

| Based on | Die Büchse der Pandora and Erdgeist by Frank Wedekind |

| Produced by | Seymour Nebenzal |

| Starring | Louise Brooks Francis Lederer Carl Goetz Alice Roberts |

| Cinematography | Günther Krampf |

Production company | Nero-Film A.G. |

| Distributed by | Süd-Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 133 minutes[a] |

| Country | Germany |

| Languages | Silent film German intertitles |

Pandora's Box (German: Die Büchse der Pandora) is a 1929 German silent drama film directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst, and starring Louise Brooks, Fritz Kortner, and Francis Lederer. The film follows Lulu, a seductive, thoughtless young woman whose raw sexuality and uninhibited nature bring ruin to herself and those who love her. It is based on Frank Wedekind's plays Erdgeist (1895) and Die Büchse der Pandora (1904).[2]

Released in 1929, Pandora's Box was a critical failure, dismissed by German critics as a bastardization of its source material. Brooks' role in the film was also subject to criticism, fueled by the fact that Brooks was an American. In the United Kingdom, France, and the United States, the film was shown in significantly truncated and re-edited versions, which eliminated certain subplots, including the film's original, downbeat ending.

By the mid-20th century, Pandora's Box was rediscovered by film scholars and began to earn a reputation as an unsung classic of Weimar German cinema.

Plot[]

Lulu is the mistress of a respected, middle-aged newspaper publisher, Dr. Ludwig Schön. One day, she is delighted when an old man, her "first patron", Schigolch, shows up at the door to her highly contemporary apartment. However, when Schön also arrives, she makes Schigolch hide on the balcony. Schön breaks the news to Lulu that he is going to marry Charlotte von Zarnikow, the daughter of the Minister of the Interior. Lulu tries to get him to change his mind, but when he discovers the disreputable-looking Schigolch, he leaves. Schigolch then introduces Lulu to Rodrigo Quast, who passed Schön on the stair. Quast wants her to join his new trapeze act.

The next day, Lulu goes to see her best friend Alwa, who happens to be Schön's son. Schön is greatly displeased to see her, but comes up with the idea to have her star in his son's musical production to get her off his hands. However, Schön makes the mistake of bringing Charlotte to see the revue. When Lulu refuses to perform in front of her rival, Schön takes her into a storage room to try to persuade her otherwise, but she seduces him instead. Charlotte finds them embracing.

A defeated Schön resigns himself to marrying Lulu. While the wedding reception is underway, he is disgusted to find Lulu playfully cavorting with Schigolch and Quast in the bedchamber. He gets his pistol and threatens to shoot the interlopers, but Lulu cries out not to, that Schigolch is her father. Schigolch and Quast thus escape. Once they are alone, Schön insists his new wife take the gun and shoot herself. When Lulu refuses, the gun goes off in the ensuing struggle, and Schön is killed.

At her murder trial, Lulu is sentenced to five years for manslaughter. However, Schigolch and Quast trigger a fire alarm and spirit her away in the confusion. When Alwa finds her back in the Schön home, he confesses his feelings for her and they decide to flee the country. Countess Augusta Geschwitz, herself infatuated with Lulu, lets the fugitive use her passport. On the train, Lulu is recognized by another passenger, Marquis Casti-Piani. He offers to keep silent in return for money. He also suggests a hiding place, a ship used as an illegal gambling den.

After several months however, Casti-Piani sells Lulu to an Egyptian for his brothel, and Quast blackmails Lulu for financing for his new act. Desperate for money to pay them off, Alwa cheats at cards, but is caught at it. Lulu turns to Schigolch for help. He has Geschwitz lure Quast to a stateroom, where she kills him. Schigolch, Lulu, and Alwa then flee.

They end up living in squalor in a drafty London garret. On Christmas Eve, driven to prostitution, Lulu has the misfortune of picking a remorseful Jack the Ripper as her first client. Though he protests he has no money, she likes him and invites him to her lodging anyway. Schigolch drags Alwa away before they are seen. Jack is touched and secretly throws away his knife. Inside, however, he spots another knife on the table and cannot resist his urge to kill Lulu. Unaware of Lulu's fate, Alwa deserts her, joining a passing Salvation Army parade.

Cast[]

- Louise Brooks as Lulu

- Fritz Kortner as Dr. Ludwig Schön

- Francis Lederer as Alwa Schön

- Carl Goetz as Schigolch

- Krafft-Raschig as Rodrigo Quast

- Alice Roberts as Countess Augusta Geschwitz

- Daisy D'ora as Charlotte Marie Adelaide von Zarnikow

- Gustav Diessl as Jack the Ripper

- Michael von Newlinsky as Marquis Casti-Piani

- Sigfried Arno as The Stage Manager

Themes[]

The film is notable for its lesbian subplot in the attraction of Countess Augusta Geschwitz (in some prints Anna) to Lulu. The character of Geschwitz is defined by her masculine look, as she wears a tuxedo. Roberts resisted the idea of playing a lesbian.[2]

The title is a reference to Pandora of Greek mythology, who upon opening a box given to her by the Olympian gods released all evils into the world, leaving only hope behind. In the film this connection is made explicitly by the prosecutor in the trial scene.

Production[]

Development[]

Pandora's Box had previously been adapted for the screen by Arzén von Cserépy in 1921 in Germany under the same title, with Asta Nielsen in the role of Lulu.[2] As there was a musical, plays and other cinema adaptations at the time, the story of Pandora's Box was well known.[2] This allowed writer-director G. W. Pabst to take liberties with the story.[2]

Casting[]

Pabst searched for months for an actress to play the lead character of Lulu.[3] After seeing American actress Louise Brooks portray a circus performer in the 1928 Howard Hawks' film A Girl in Every Port, Pabst tried to get her on loan from Paramount Pictures.[4] His offer was not made known to Brooks by the studio until she left Paramount over a salary dispute. Pabst's second choice was Marlene Dietrich; Dietrich was actually in Pabst's office, waiting to sign a contract to do the film, when Pabst got word of Brooks' availability.[4] In an interview many years later, Brooks stated that Pabst was reluctant to hire Dietrich, as he felt she was too old at 27, and not a good fit for the character.[3] Pabst himself later wrote that Dietrich was too knowing, while Brooks had both innocence and the ability to project sexuality, without coyness or premeditation.[5]

Filming[]

"I revered Pabst for his truthful picture of this world of pleasure, which let me play Lulu naturally. The rest of the cast were tempted to rebellion."

–Brooks on the filming experience, 1965[6]

In shooting the film, Pabst drew on Brooks' background as a dancer with the pioneering modern dance ensemble Denishawn, "choreographing" the movement in each scene and limiting her to a single emotion per shot.[5] Pabst was deft in manipulating his actors: he hired tango musicians to inspire Brooks between takes, coached a reluctant Alice Roberts through the lesbian sequences, and appeased Fritz Kortner, who did not hide his dislike for Brooks.[5] During the first week or two of filming, Brooks went out partying every night with her current lover, George Preston Marshall, much to Pabst's displeasure.[7] When Marshall left, a relieved Pabst imposed a stricter lifestyle on his star.

Tensions rose between the performers as well, with Fritz Kortner refusing to speak to Brooks on the set.[8] Per Brooks' own recollection, "Kortner, like everybody else on the production, thought I had cast some blinding spell over Pabst that allowed me to walk through my part... Kortner hated me. After each scene with me, he would pound off the set to his dressing room."[9] Despite these tensions, Brooks reflected that Pabst used the actors' personal animosities and dispositions toward one another to the benefit of the film's character dynamics, subtly urging them to sublimate their frustrations, and recalled his direction as masterful.[10]

Release[]

Reception and censorship[]

Upon the film's release in Germany, Pabst was accused of making a "scandalous version" of Wedekind's plays, in which the Lulu character is presented as "a man-eater devouring her sexual victims."[11] Critics in Berlin particularly dismissed the film as a "travesty" of its source material.[12] The film's presentation of the Countess as a lesbian was also controversial, and Brooks was castigated as a "non-actress."[11] According to film historians Derek Malcolm and J. Hoberman, the ire Brooks received for her performance was largely rooted in her being an American.[11][12]

The film underwent significant censorship in various countries: In France, the film was significantly re-edited from its original cut, making Alwa's secretary and the countess become Lulu's childhood friends, eliminating the lesbian subplot between the countess and Lulu; furthermore, in the French cut, Lulu is found not guilty at her trial, and there is no Jack the Ripper character, as the film ends with Lulu joining the Salvation Army.[13] This cut was also released in the United Kingdom.[11] Significantly truncated cuts of the film were screened in the United States, ranging various lengths, and concluding the same as the French and British cuts, with Lulu escaping to join the Salvation Army.[14]

U.S. reviews[]

In the United States, the film screened in New York City beginning 1 December 1929, also in a truncated version.[15] Film critic Irene Thirer of the New York Daily News noted that the film suffered greatly from the edits made to what "must have been ultra-sophisticated silent cinema in its original form."[15] On 8 December 1929, the widely read New York-based trade paper The Film Daily also published a review; that assessment, written by Jack Harrower, was based too on his viewing a heavily censored version of the film, a version identified to have a running time of only 66 minutes.[16] Harrower describes what he saw as a "hodgepodge" that offers "little entertainment" due to the film being "hacked to pieces by the censors":[16]

Louise Brooks, the American actress, has the part of an exotic girl who attracts both men and women. She is a sort of unconscious siren who leads men to near-doom although her motives are apparently quite innocent.... A sweet ending has been tacked on to satisfy the censors, and with the rest of the cuts, it is a very incoherent film. It is too sophisticated for any but art theater audiences. G. W. Pabst's direction is clever, but the deletions have killed that, too.[16]

Variety, the American entertainment industry's leading publication in 1929, characterizes Pandora's Box as incoherent or "rambling" in its 11 December review.[17] That review, attributed to "Waly", was based on the film's presentation at the 55th Street Playhouse in Manhattan, which apparently screened a longer version of the motion picture than the one seen by Harrower. Variety's critic estimated the duration of the film he saw at 85 minutes; nevertheless, he also recognized the ruinous effects of extensive cuts to the film. "Management at this house [theater]", notes Waly, "blames the N.Y. censor with ending everything with Pandora and boy friends joining the Salvation Army."[17]

The New York Times reviewed the film as well in December 1929. The newspaper's influential critic Mordaunt Hall also saw the picture at Manhattan's 55th Street Playhouse. Hall in his review judges it to be "a disconnected melodramatic effusion" that is "seldom interesting".[18] He notes that Brooks is "attractive" and "moves her head and eyes at the proper moment", but he adds that he finds her facial expressions in portraying various emotions on screen "often difficult to decide".[18] Hall then concludes his remarks by indirectly complimenting the film's cinematography, asserting that the German production was "filmed far better than the story deserves".[18]

Rediscovery and restoration[]

Though it was largely dismissed by critics upon initial release, Pandora's Box was rediscovered among film scholars in the 1950s, and began to accrue acclaim, eventually earning the reputation of being an unsung classic.[2][19] Contemporarily, it is considered one of the classics of Weimar Germany's cinema, along with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Metropolis, The Last Laugh, and The Blue Angel.[2][20] Brooks' talent as an actress, which had been criticized upon the film's initial release (specifically by German critics), was also subject to international reappraisal and acclaim from the likes of European critics such as Lotte H. Eisner, Henri Langlois, and David Thomson.[21]

Film critic Roger Ebert reviewed the film in 1998 with great praise, and remarked of Brooks' presence that "she regards us from the screen as if the screen were not there; she casts away the artifice of film and invites us to play with her". He included the film on his list of The Great Movies.[22] As of 2020, the film has a 92% approval rating on internet review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 36 reviews, with a weighted average of 8.82/10.[20]

In 2009, Hugh Hefner funded a restoration of the film.[23] This restoration was screened at the 2012 San Francisco Silent Film Festival.[24] In their program, the festival noted: "As a heavily censored film that deals with the psychological effects of sexual repression, Pandora’s Box meets two of Hefner’s charitable objectives: artistic expression and a pristine new film, both finally unfurled after decades of frustration."[24]

Quentin Tarantino listed the movie among his 10 greatest films of all time.[25]

Home media[]

In the United Kingdom, Pandora's Box was released on DVD on 24 June 2002, by Second Sight Films.[26][27]

In North America, Pandora's Box was released on a two-disc DVD set on 28 November 2006, by The Criterion Collection.[28] Four soundtracks were commissioned for the film's DVD release: an approximation of the score cinema audiences might have heard with a live orchestra, a Weimar Republic-era cabaret score, a modern orchestral interpretation, and an improvisational piano score.[28]

See also[]

- List of German films 1919–1933

- News for Lulu (Jazz album)

- Pandora's Box (Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark song)

Notes[]

- ^ While various truncated cuts of the film were shown in the United States and other countries, the director's cut of the film, which appears on the 2006 Criterion Collection DVD, runs 133 minutes; this cut was passed by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) "uncut" in 2002.[1]

References[]

- ^ "Pandora's Box". British Board of Film Classification. 30 June 2002. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Pandora's Box (Commentary). G. W. Pabst. New York City, New York: The Criterion Collection. 2006 [1929]. CC1656D.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brooks 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoberman 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Carr, Jay. "Pandora's Box". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020.

- ^ Brooks 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Hoberman 2006, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Brooks 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Brooks 2006, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Brooks 2006, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Malcolm, Derek (21 July 1999). "GW Pabst: Pandora's Box". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoberman 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Hoberman 2006, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Hoberman 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thirer, Irene (3 December 1929). "'Pandora's Box' Silent Film at 55th Street Playhouse". New York Daily News. p. 40 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Harrower, Jack (1929). "Louise Brooks in 'Pandora's Box' (Silent)", review, The Film Daily (New York, N.Y.), 8 December 1929, p. 8. Internet Archive, San Francisco. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Waly" (1929). "Pandora's Box (German made)/(Silent)", Variety (New York, N.Y.), 11 December 1929, p. 39. Internet Archive. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hall, Mordaunt (1929). "THE SCREEN; Paris in '70 and '71", review, The New York Times, 2 December 1929. NYT digital archives. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Gladysz, Thomas (7 December 2017). "The BFI Re-Opens Silent Film 'Pandora's Box'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pandora's Box". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Tynan 2006, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (26 April 1998). "Pandora's Box". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012.

- ^ Hutchinson 2020, p. 102.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Preservationist and the Playboy: Restoring Pandora's Box". San Francisco Silent Film Festival. 2012. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino's handwritten list of the 11 greatest films of all time". Far Out Magazine.

- ^ "Second Sight - Classic Film on TV and DVD". Second Sight Films. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ "Pandora's Box (Overview)". Allmovie. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Die Buchse der Pandora [2 Discs]". Allmovie. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

Sources[]

- Brooks, Louise (2006) [1965]. Pabst and Lulu. Reflections on Pandora's Box (DVD liner booklet). The Criterion Collection. pp. 74–93. CC1656D.

- Hutchinson, Pamela (2020). Pandora's Box (Die Büchse der Pandora). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-838-71974-6.

- Hoberman, J. (2006). Opening Pandora's Box. Reflections on Pandora's Box (DVD liner booklet). The Criterion Collection. pp. 7–12. CC1656D.

- Tynan, Kenneth (2006) [1979]. The Girl in the Black Helmet. Reflections on Pandora's Box (DVD liner booklet). The Criterion Collection. pp. 20–74. CC1656D.

External links[]

- Pandora's Box at IMDb

- Pandora's Box at the TCM Movie Database

- Pandora's Box at SilentEra

- Pandora's Box at AllMovie

- Pandora's Box at Rotten Tomatoes

- Opening Pandora’s Box an essay by J. Hoberman at the Criterion Collection

- Full plot summary and cast and crew biographies.

- 1929 films

- 1929 drama films

- German drama films

- German films

- Films of the Weimar Republic

- German silent feature films

- Films directed by G. W. Pabst

- Films based on works by Frank Wedekind

- German black-and-white films

- German films based on plays

- Films about prostitution in Germany

- Lesbian-related films

- Films set in Berlin

- Films set in London

- Films set in the 1880s

- Films about Jack the Ripper

- Films produced by Seymour Nebenzal

- Melodramas

- 1920s LGBT-related films