Paradise Lost

Title page of the first edition (1667) | |

| Author | John Milton |

|---|---|

| Cover artist |

|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | Samuel Simmons (original) |

Publication date | 1667 |

| Media type | |

| Followed by | Paradise Regained |

| Text | Paradise Lost at Wikisource |

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 1674, arranged into twelve books (in the manner of Virgil's Aeneid) with minor revisions throughout.[1][2] It is considered to be Milton's masterpiece, and it helped solidify his reputation as one of the greatest English poets of his time.[3] The poem concerns the biblical story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

Composition[]

In his introduction to the Penguin edition of Paradise Lost, the Milton scholar John Leonard notes, "John Milton was nearly sixty when he published Paradise Lost in 1667. The biographer John Aubrey (1626–97) tells us that the poem was begun in about 1658 and finished in about 1663. However, parts were almost certainly written earlier, and its roots lie in Milton's earliest youth."[4] Leonard speculates that the English Civil War interrupted Milton's earliest attempts to start his "epic [poem] that would encompass all space and time."[4]

Leonard also notes that Milton "did not at first plan to write a biblical epic."[4] Since epics were typically written about heroic kings and queens (and with pagan gods), Milton originally envisioned his epic to be based on a legendary Saxon or British king like the legend of King Arthur.[5][6]

Having gone blind in 1652, Milton wrote Paradise Lost entirely through dictation with the help of amanuenses and friends. He also wrote the epic poem while he was often ill, suffering from gout, and despite suffering emotionally after the early death of his second wife, Katherine Woodcock, in 1658, and the death of their infant daughter.[7]

Structure[]

[...] this with her who bore

Scipio the highth of Rome. With tract oblique

At first, as one who sought access, but feard

To interrupt, side-long he works his way.

As when a Ship by skilful Stearsman wrought

Nigh Rivers mouth or Foreland, where the Wind

Veres oft, as oft so steers, and shifts her Saile [...][8]

John Milton, Paradise Lost, 9.509-15. (Emphasis added)

In the 1667 version of Paradise Lost, the poem was divided into ten books. However, in the 1672 edition, the text was reorganized into twelve books.[9] In later printing, "Arguments" (brief summaries) were inserted at the beginning of each book.[10]

Milton used a number of acrostics in the poem. In Book 9, a verse describing the serpent which tempted Eve to eat the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden spells out "SATAN" (9.510), while elsewhere in the same book, Milton spells out "FFAALL" and "FALL" (9.333). Respectively, these probably represent the double fall of humanity embodied in Adam and Eve, as well as Satan's fall from Heaven.[11]

Synopsis[]

The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (in the midst of things), the background story being recounted later.

Milton's story has two narrative arcs, one about Satan (Lucifer) and the other, Adam and Eve. It begins after Satan and the other fallen angels have been defeated and banished to Hell, or, as it is also called in the poem, Tartarus. In Pandæmonium, the capital city of Hell, Satan employs his rhetorical skill to organise his followers; he is aided by Mammon and Beelzebub. Belial and Moloch are also present. At the end of the debate, Satan volunteers to corrupt the newly created Earth and God's new and most favoured creation, Mankind. He braves the dangers of the Abyss alone, in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas. After an arduous traversal of the Chaos outside Hell, he enters God's new material World, and later the Garden of Eden.

At several points in the poem, an Angelic War over Heaven is recounted from different perspectives. Satan's rebellion follows the epic convention of large-scale warfare. The battles between the faithful angels and Satan's forces take place over three days. At the final battle, the Son of God single-handedly defeats the entire legion of angelic rebels and banishes them from Heaven. Following this purge, God creates the World, culminating in his creation of Adam and Eve. While God gave Adam and Eve total freedom and power to rule over all creation, he gave them one explicit command: not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil on penalty of death.

The story of Adam and Eve's temptation and fall is a fundamentally different, new kind of epic: a domestic one. Adam and Eve are presented as having a romantic and sexual relationship while still being without sin. They have passions and distinct personalities. Satan, disguised in the form of a serpent, successfully tempts Eve to eat from the Tree by preying on her vanity and tricking her with rhetoric. Adam, learning that Eve has sinned, knowingly commits the same sin. He declares to Eve that since she was made from his flesh, they are bound to one another – if she dies, he must also die. In this manner, Milton portrays Adam as an heroic figure, but also as a greater sinner than Eve, as he is aware that what he is doing is wrong.

After eating the fruit, Adam and Eve have lustful sex. At first, Adam is convinced that Eve was right in thinking that eating the fruit would be beneficial. However, they soon fall asleep and have terrible nightmares, and after they awake, they experience guilt and shame for the first time. Realising that they have committed a terrible act against God, they engage in mutual recrimination.

Meanwhile, Satan returns triumphantly to Hell, amid the praise of his fellow fallen angels. He tells them about how their scheme worked and Mankind has fallen, giving them complete dominion over Paradise. As he finishes his speech, however, the fallen angels around him become hideous snakes, and soon enough, Satan himself turns into a snake, deprived of limbs and unable to talk. Thus, they share the same punishment, as they shared the same guilt.

Eve appeals to Adam for reconciliation of their actions. Her encouragement enables them to approach God, and sue for grace, bowing on supplicant knee, to receive forgiveness. In a vision shown to him by the Archangel Michael, Adam witnesses everything that will happen to Mankind until the Great Flood. Adam is very upset by this vision of the future, so Michael also tells him about Mankind's potential redemption from original sin through Jesus Christ (whom Michael calls "King Messiah").

Adam and Eve are cast out of Eden, and Michael says that Adam may find "a paradise within thee, happier far." Adam and Eve now have a more distant relationship with God, who is omnipresent but invisible (unlike the tangible Father in the Garden of Eden).

Characters[]

Satan[]

Satan, formerly called Lucifer, is the first major character introduced in the poem. He was once the most beautiful of all angels,[citation needed] and is a tragic figure who famously declares: "Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven" (1.263). Following his vain rebellion against God he is cast out from Heaven and condemned to Hell. The rebellion stems from Satan's pride and envy (5.660ff.). He explains his intention to Abdiel, one of God's faithful:

by proof to try

Who is our equal: then thou shalt behold

Whether by supplication we intend

Address, and to begirt th' Almighty Throne

Beseeching or besieging. (5.865-69)

Satan is powerful and charismatic. His persuasive powers are evident throughout the book. He is not only cunning and deceptive: he is also able to rally the fallen angels to continue in the rebellion after their agonizing defeat in the Angelic War. Though commonly understood to be the antagonizing force in Paradise Lost,[citation needed] Satan may be best defined as a tragic or Hellenic hero. According to William McCollom one quality of the classical tragic hero is that he is not perfectly good and that his defeat is caused by a tragic flaw. Satan causes both the downfall of man and the eternal damnation of his fellow fallen angels despite his dedication to his comrades. In addition, Satan's Hellenic qualities, such as his immense courage and, perhaps, lack of completely defined morals compound his tragic nature.[12][clarification needed]

Satan's status as a protagonist in the epic poem is debated.[citation needed] Milton characterizes him as such,[citation needed] but Satan lacks several key traits that would otherwise make him the definitive protagonist in the work. One deciding factor that insinuates his role as the protagonist in the story is that most often a protagonist is heavily characterized and far better described than the other characters, and the way the character is written is meant to make him seem more interesting or special to the reader.[13] For that matter, Satan is both well described and is depicted as being quite versatile in that he is shown as having the capacity to do evil while retaining his characteristic sympathetic qualities and thus it is this complex and relatable nature that makes him a likely candidate for the story's overarching protagonist.[13][clarification needed]

By some definitions a protagonist must be able to exist in and of themselves and the secondary characters in the work exist only to further the plot for the protagonist.[14] Because Satan does not exist solely for himself, as without God he would not have a role to play in the story, he may not be viewed as the protagonist because of the continual shifts in perspective and relative importance of characters in each book of the work. Satan's existence in the story involves his rebellion against God, and his determination to corrupt the beings which God creates, in order to perpetuate evil so that there can be a discernible balance and justice for both himself and his fallen angels.[clarification needed] Therefore, it is more probable that he exists in order to combat God, making his status as the definitive protagonist of the work relative to each book. Following this logic, Satan may very well be considered as an antagonist in the poem, whereas God could be considered as the protagonist instead.

Satan's status as a traditional hero in the work is similarly up to debate as the term "hero" evokes different meanings depending on the time and the person giving the definition, and is thus a matter of contention within the text. According to Aristotle, a hero is someone who is "superhuman, godlike, and divine" but is also human.[15] A hero would have to either be a human with God-like powers or the offspring of God. While Milton gives reason to believe that Satan is superhuman, as he was originally an angel, he is anything but human.[clarification needed] However, one could argue that Satan's faults make him more human than any other divine being described in Milton's work, as Torquato Tasso and Francesco Piccolomini expanded on Aristotle's definition, and declared that to be heroic one has to be perfectly or overly virtuous.[16] In this regard, Satan repeatedly demonstrates a lack of virtue throughout the story as he intends to tempt God's creations with evil in order to destroy the good which God is trying to create. Therefore, Satan is not a hero according to Tasso and Piccolomini's expanded definition. Satan goes against God's law and therefore becomes corrupt and lacking of virtue, and, as Piccolomini warned, "vice may be mistaken for heroic virtue."[15] Satan is very devoted to his cause. His cause is evil but he strives to spin his sinister aspirations to appear as good ones.[citation needed] Satan achieves this end multiple times throughout the text as he riles up his band of fallen angels during his speech by deliberately telling them to do evil to explain God's hypocrisy and again during his entreaty to Eve.[clarification needed] He makes his intentions seem pure and positive even when they are rooted in evil and, according to Steadman, this is the chief reason that readers often mistake Satan as a hero.[16]

Although Satan's army inevitably loses the war against God, Satan achieves a position of power and begins his reign in Hell with his band of loyal followers, composed of fallen angels, which is described to be a "third of heaven." Satan's characterization as the leader of a failing cause folds into this as well and is best exemplified through his own quote,[clarification needed]

Fall'n Cherube, to be weak is miserable

Doing or Suffering: but of this be sure,

To do ought good never will be our task,

But ever to do ill our sole delight,

As being the contrary to his high will

Whom we resist. If then his Providence

Out of our evil seek to bring forth good,

Our labour must be to pervert that end,

And out of good still to find means of evil;

Which oft times may succeed, so as perhaps

Shall grieve him, if I fail not, and disturb

His inmost counsels from thir destind aim. (1.157-68)

as through shared solidarity espoused by empowering rhetoric, Satan riles up his comrades in arms and keeps them focused towards their shared goal.[17] Similar to Milton's republican sentiments of overthrowing the King of England for both better representation and parliamentary power, Satan argues that his shared rebellion with the fallen angels is an effort to "explain the hypocrisy of God,"[citation needed] and in doing so, they will be treated with the respect and acknowledgement that they deserve. As scholar Wayne Rebhorn argues, "Satan insists that he and his fellow revolutionaries held their places by right and even leading him to claim that they were self-created and self-sustained" and thus Satan's position in the rebellion is much like that of his own real world creator.[18]

Adam[]

Adam is the first human created by God. Adam requests a companion from God:

Of fellowship I speak

Such as I seek, fit to participate

All rational delight, wherein the brute

Cannot be human consort. (8.389-92)

God approves his request then creates Eve. God appoints Adam and Eve to rule over all the creatures of the world and to reside in the Garden of Eden.

Adam is more gregarious than Eve and yearns for her company. He is completely infatuated with her. Raphael advises him to "take heed lest Passion sway / Thy Judgment" (5.635-36). But Adam's great love for Eve contributes to his disobedience to God.

Unlike the biblical Adam, before Milton's Adam leaves Paradise he is given a glimpse of the future of mankind by the Archangel Michael, which includes stories from the Old and New Testaments.

Eve[]

Eve is the second human created by God. God takes one of Adam's ribs and shapes it into Eve. Whether Eve is actually inferior to Adam is a vexed point. She is often unwilling to be submissive. Eve may be the more intelligent of the two. She is generally happy, but longs for knowledge, specifically for self-knowledge.[citation needed] When she first met Adam she turned away, more interested in herself. She had been looking at her reflection in a lake before being led invisibly to Adam. Recounting this to Adam she confesses that she found him

less faire,

Less winning soft, less amiablie milde,

Then that smooth watry image. (4.477-80)

Nonetheless Adam later explains this to Raphael as Eve's

Innocence and Virgin Modestie,

Her vertue and the conscience of her worth,

That would be woo'd, and not unsought be won. (8.501-03)

But Adam's judgment is not always sound. And Eve is beautiful.

Though Eve does love Adam she may feel suffocated by his constant presence.[citation needed] In Book 9 she convinces Adam to separate for a time to work in different parts of the Garden. In her solitude she is deceived by Satan. Satan in the serpent leads Eve to the forbidden tree then persuades her that he has eaten of its fruit and gained knowledge and that she should do the same. She is not easily persuaded to eat, but is hungry in body and in mind.

The Son of God[]

The Son of God is the spirit who will become incarnate as Jesus Christ, though he is never named explicitly because he has not yet entered human form. Milton believed in a subordinationist doctrine of Christology that regarded the Son as secondary to the Father and as God's "great Vice-regent" (5.609).

Hear all ye Angels, Progenie of Light,

Thrones, Dominations, Princedoms, Vertues, Powers,

Hear my Decree, which unrevok't shall stand.

This day I have begot whom I declare

My onely Son, and on this holy Hill

Him have anointed, whom ye now behold

At my right hand; your Head I him appoint;

And by my Self have sworn to him shall bow

All knees in Heav'n, and shall confess him Lord:

Under his great Vice-gerent Reign abide

United as one individual Soule

For ever happie: him who disobeyes

Mee disobeyes, breaks union, and that day

Cast out from God and blessed vision, falls

Into utter darkness, deep ingulft, his place

Ordaind without redemption, without end.

John Milton, Paradise Lost, 5.600-15.

Milton's God in Paradise Lost refers to the Son as "My word, my wisdom, and effectual might" (3.170). The poem is not explicitly anti-trinitarian, but it is consistent with Milton's convictions. The Son is the ultimate hero of the epic and is infinitely powerful—he single-handedly defeats Satan and his followers and drives them into Hell. After their fall, the Son of God tells Adam and Eve about God's judgment. Before their fall the Father foretells their "Treason" (3.207) and that Man

with his whole posteritie must dye,

Dye hee or Justice must; unless for him

Som other able, and as willing, pay

The rigid satisfaction, death for death. (3.210-12)

The Father then asks whether there "Dwels in all Heaven charitie so deare?" (3.216) And the Son volunteers himself.

In the final book a vision of Salvation through the Son is revealed to Adam by Michael. The name Jesus of Nazareth, and the details of Jesus' story are not depicted in the poem,[19] though they are alluded to. Michael explains that "Joshua, whom the Gentiles Jesus call," prefigures the Son of God, "his name and office bearing" to "quell / The adversarie Serpent, and bring back [...] long wander[e]d man / Safe to eternal Paradise of rest."[20]

God the Father[]

God the Father is the creator of Heaven, Hell, the world, of everyone and everything there is, through the agency of His Son. Milton presents God as all-powerful and all-knowing, as an infinitely great being who cannot be overthrown by even the great army of angels Satan incites against him. Milton portrays God as often conversing about his plans and his motives for his actions with the Son of God. The poem shows God creating the world in the way Milton believed it was done, that is, God created Heaven, Earth, Hell, and all the creatures that inhabit these separate planes from part of Himself, not out of nothing.[21] Thus, according to Milton, the ultimate authority of God over all things that happen derives from his being the "author" of all creation. Satan tries to justify his rebellion by denying this aspect of God and claiming self-creation, but he admits to himself the truth otherwise, and that God "deserved no such return/ From me, whom He created what I was."[22][23]

Raphael[]

Raphael is an affable archangel whom God sends to Eden:

half this day as friend with friend

Converse with Adam, [...]

and such discourse bring on,

As may advise him of his happie state,

Happiness in his power left free to will,

Left to his own free Will, his Will though free,

Yet mutable; whence warne him to beware

He swerve not too secure: tell him withall

His danger, and from whom, what enemie

Late falln himself from Heav'n, is plotting now

The fall of others from like state of bliss;

By violence, no, for that shall be withstood,

But by deceit and lies; this let him know,

Lest wilfully transgressing he pretend

Surprisal, unadmonisht, unforewarnd. (5.229-45)

Raphael discusses at length with the curious Adam what has transpired and pertains to present and future happiness. He admonishes Adam kindly. The extent to which Eve is present with or interested in Raphael is unclear.

Michael[]

Michael is an archangel who is preeminent in military prowess. He leads in battle and uses a sword which was "giv'n him temperd so, that neither keen / Nor solid might resist that edge" (6.322-23).

God sends Michael to Eden, charging him:

from the Paradise of God

Without remorse drive out the sinful Pair

From hallowd ground th' unholie, and denounce

To them and to thir Progenie from thence

Perpetual banishment. [...]

If patiently thy bidding they obey,

Dismiss them not disconsolate; reveale

To Adam what shall come in future dayes,

As I shall thee enlighten, intermix

My Cov'nant in the womans seed renewd;

So send them forth, though sorrowing, yet in peace. (11.103-17)

He is also charged with establishing a guard for Paradise.

When Adam sees him coming he describes him to Eve as

not terrible,

That I should fear, nor sociably mild,

As Raphael, that I should much confide,

But solemn and sublime, whom not to offend,

With reverence I must meet, and thou retire. (11.233-37)

Motifs[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (February 2021) |

Marriage[]

Milton first presented Adam and Eve in Book IV with impartiality. The relationship between Adam and Eve is one of "mutual dependence, not a relation of domination or hierarchy." While the author placed Adam above Eve in his intellectual knowledge and, in turn, his relation to God, he granted Eve the benefit of knowledge through experience. Hermine Van Nuis clarifies, that although there was stringency specified for the roles of male and female, Adam and Eve unreservedly accept their designated roles.[24] Rather than viewing these roles as forced upon them, each uses their assignment as an asset in their relationship with each other. These distinctions can be interpreted as Milton's view on the importance of mutuality between husband and wife.

When examining the relationship between Adam and Eve, some critics apply either an Adam-centered or Eve-centered view of hierarchy and importance to God. David Mikics argues, by contrast, these positions "overstate the independence of the characters' stances, and therefore miss the way in which Adam and Eve are entwined with each other."[25] Milton's narrative depicts a relationship where the husband and wife (here, Adam and Eve) depend on each other and, through each other's differences, thrive.[25] Still, there are several instances where Adam communicates directly with God while Eve must go through Adam to God; thus, some have described Adam as her guide.[26]

Although Milton does not directly mention divorce, critics posit theories on Milton's view of divorce based upon their inferences from the poem and from his tracts on divorce written earlier in his life. Other works by Milton suggest he viewed marriage as an entity separate from the church. Discussing Paradise Lost, Biberman entertains the idea that "marriage is a contract made by both the man and the woman."[27] These ideas imply Milton may have favored that both man and woman have equal access to marriage and to divorce.

Idolatry[]

Milton's 17th-century contemporaries by and large criticised his ideas and considered him as a radical, mostly because of his Protestant views on politics and religion. One of Milton's most controversial arguments centred on his concept of what is idolatrous, which subject is deeply embedded in Paradise Lost.

Milton's first criticism of idolatry focused on the constructing of temples and other buildings to serve as places of worship. In Book XI of Paradise Lost, Adam tries to atone for his sins by offering to build altars to worship God. In response, the angel Michael explains that Adam does not need to build physical objects to experience the presence of God.[28] Joseph Lyle points to this example, explaining "When Milton objects to architecture, it is not a quality inherent in buildings themselves he finds offensive, but rather their tendency to act as convenient loci to which idolatry, over time, will inevitably adhere."[29] Even if the idea is pure in nature, Milton thought it would unavoidably lead to idolatry simply because of the nature of humans. That is, instead of directing their thoughts towards God, humans will turn to erected objects and falsely invest their faith there. While Adam attempts to build an altar to God, critics note Eve is similarly guilty of idolatry, but in a different manner. Harding believes Eve's narcissism and obsession with herself constitutes idolatry.[30] Specifically, Harding claims that "... under the serpent's influence, Eve's idolatry and self-deification foreshadow the errors into which her 'Sons' will stray."[30] Much like Adam, Eve falsely places her faith in herself, the Tree of Knowledge, and to some extent the Serpent, all of which do not compare to the ideal nature of God.

Milton made his views on idolatry more explicit with the creation of Pandæmonium and his allusion to Solomon's temple. In the beginning of Paradise Lost and throughout the poem, there are several references to the rise and eventual fall of Solomon's temple. Critics elucidate that "Solomon's temple provides an explicit demonstration of how an artefact moves from its genesis in devotional practice to an idolatrous end."[31] This example, out of the many presented, distinctly conveys Milton's views on the dangers of idolatry. Even if one builds a structure in the name of God, the best of intentions can become immoral in idolatry. Further, critics have drawn parallels between both Pandemonium and Saint Peter's Basilica,[citation needed] and the Pantheon. The majority of these similarities revolve around a structural likeness, but as Lyle explains, they play a greater role. By linking Saint Peter's Basilica and the Pantheon to Pandemonium—an ideally false structure—the two famous buildings take on a false meaning.[32] This comparison best represents Milton's Protestant views, as it rejects both the purely Catholic perspective and the Pagan perspective.

In addition to rejecting Catholicism, Milton revolted against the idea of a monarch ruling by divine right. He saw the practice as idolatrous. Barbara Lewalski concludes that the theme of idolatry in Paradise Lost "is an exaggerated version of the idolatry Milton had long associated with the Stuart ideology of divine kingship."[33] In the opinion of Milton, any object, human or non-human, that receives special attention befitting of God, is considered idolatrous.

Interpretation and critique[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (February 2021) |

The writer and critic Samuel Johnson wrote that Paradise Lost shows off "[Milton's] peculiar power to astonish" and that "[Milton] seems to have been well acquainted with his own genius, and to know what it was that Nature had bestowed upon him more bountifully than upon others: the power of displaying the vast, illuminating the splendid, enforcing the awful, darkening the gloomy, and aggravating the dreadful."[34]

Milton scholar John Leonard interpreted the "impious war" between Heaven and Hell as civil war:[35][page needed]

Paradise Lost is, among other things, a poem about civil war. Satan raises 'impious war in Heav'n' (i 43) by leading a third of the angels in revolt against God. The term 'impious war' implies that civil war is impious. But Milton applauded the English people for having the courage to depose and execute King Charles I. In his poem, however, he takes the side of 'Heav'n's awful Monarch' (iv 960). Critics have long wrestled with the question of why an antimonarchist and defender of regicide should have chosen a subject that obliged him to defend monarchical authority.

The editors at the Poetry Foundation argue that Milton's criticism of the English monarchy was being directed specifically at the Stuart monarchy and not at the monarchy system in general.[3]

In a similar vein, critic and writer C.S. Lewis argued that there was no contradiction in Milton's position in the poem since "Milton believed that God was his 'natural superior' and that Charles Stuart was not." Lewis interpreted the poem as a genuine Christian morality tale.[35][page needed] Other critics, like William Empson, view it as a more ambiguous work, with Milton's complex characterization of Satan playing a large part in that perceived ambiguity.[35][page needed] Empson argued that "Milton deserves credit for making God wicked, since the God of Christianity is 'a wicked God.'" Leonard places Empson's interpretation "in the [Romantic interpretive] tradition of William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley."[35][page needed]

Blake famously wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: "The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it."[36] This quotation succinctly represents the way in which some 18th- and 19th-century English Romantic poets viewed Milton.

Speaking of the complexity of Milton's epic are John Rogers' lectures which try their best to synthesize the "advantages and limitations of a diverse range of interpretive techniques and theoretical concerns in Milton scholarship and criticism."[37]

Empson's view is complex. Leonard points out that "Empson never denies that Satan's plan is wicked. What he does deny is that God is innocent of its wickedness: 'Milton steadily drives home that the inmost counsel of God was the Fortunate Fall of man; however wicked Satan's plan may be, it is God's plan too [since God in Paradise Lost is depicted as being both omniscient and omnipotent].'"[35][page needed] Leonard calls Empson's view "a powerful argument"; he notes that this interpretation was challenged by in his book Milton's Good God (1982).[35][page needed]

Christian epic[]

Milton was not the first to write an epic poem on a Christian theme. There are some well-known precursors:

- La Battaglia celeste tra Michele e Lucifero (1568), by ;

- La Sepmaine (1578), by Guillaume Du Bartas;

- La Gerusalemme liberata (1581), by Torquato Tasso;

- Angeleida (1590), by ;

- Le sette giornate del mondo creato (1607), by Tasso;

- De la creación del mundo (1615), by .

On the other hand, according to Tobias Gregory, he was:

the most theologically learned among early modern epic poets. He was, moreover, a theologian of great independence of mind, and one who developed his talents within a society where the problem of divine justice was debated with particular intensity.[38]

He is able to establish divine action and his divine characters in a superior way to other Renaissance epic poets, including Ludovico Ariosto or Tasso.[39]

In Paradise Lost Milton also ignores the traditional epic format, which started with Homer, of a plot based on a mortal conflict between opposing armies with deities watching over and occasionally interfering with the action. Instead, both divinity and mortal are involved in a conflict that, while momentarily ending in tragedy, offers a future salvation.[39] In both Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, Milton incorporates aspects of Lucan's epic model, the epic from the view of the defeated. Although he does not accept the model completely within Paradise Regained, he incorporates the "anti-Virgilian, anti-imperial epic tradition of Lucan".[40] Milton goes further than Lucan in this belief and "Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained carry further, too, the movement toward and valorization of romance that Lucan's tradition had begun, to the point where Milton's poems effectively create their own new genre".[41]

Blank verse[]

Blank verse was not much used in the non-dramatic poetry of the 17th century until Paradise Lost, in which Milton used it with much license and tremendous skill. Milton used the flexibility of blank verse, its capacity to support syntactic complexity, to the utmost, in passages such as these:

....Into what Pit thou seest

From what highth fal'n, so much the stronger provd

He with his Thunder: and till then who knew

The force of those dire Arms? yet not for those

Nor what the Potent Victor in his rage

Can else inflict do I repent or change,

Though chang'd in outward lustre; that fixt mind

And high disdain, from sence of injur'd merit,

That with the mightiest rais'd me to contend,

And to the fierce contention brought along

Innumerable force of Spirits arm'd

That durst dislike his reign, and me preferring,

His utmost power with adverse power oppos'd

In dubious Battel on the Plains of Heav'n,

And shook his throne. What though the field be lost?

All is not lost; the unconquerable Will,

And study of revenge, immortal hate,

And courage never to submit or yield:— Paradise Lost, Book 1[42]

Milton also wrote Paradise Regained and parts of Samson Agonistes in blank verse.

Although Milton was not the first to use blank verse, his use of it was very influential and he became known for the style. When Miltonic verse became popular, Samuel Johnson mocked Milton for inspiring bad blank verse, but he recognized that Milton's verse style was very influential.[43] Poets such as Alexander Pope, whose final, incomplete work was intended to be written in the form,[44] and John Keats, who complained that he relied too heavily on Milton,[45] adopted and picked up various aspects of his poetry. In particular, Miltonic blank verse became the standard for those attempting to write English epics for centuries following the publication of Paradise Lost and his later poetry.[46] The poet Robert Bridges analyzed his versification in the monograph Milton's Prosody.

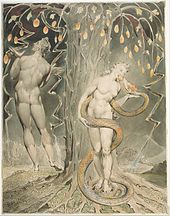

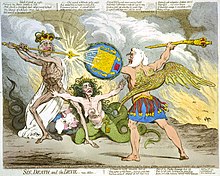

Iconography[]

The first illustrations to accompany the text of Paradise Lost were added to the fourth edition of 1688, with one engraving prefacing each book, of which up to eight of the twelve were by Sir John Baptist Medina, one by Bernard Lens II, and perhaps up to four (including Books I and XII, perhaps the most memorable) by another hand.[47] The engraver was Michael Burghers (given as 'Burgesse' in some sources[48]). By 1730 the same images had been re-engraved on a smaller scale by Paul Fourdrinier.

Some of the most notable illustrators of Paradise Lost included William Blake, Gustave Doré, and Henry Fuseli. However, the epic's illustrators also include John Martin, Edward Francis Burney, Richard Westall, Francis Hayman, and many others.

Outside of book illustrations, the epic has also inspired other visual works by well-known painters like Salvador Dalí who executed a set of ten colour engravings in 1974.[49] Milton's achievement in writing Paradise Lost while blind (he dictated to helpers) inspired loosely biographical paintings by both Fuseli[50] and Eugène Delacroix.[51]

See also[]

- Paradise Lost in popular culture

- John Milton's poetic style

- Paradise Regained

- Visio Tnugdali

- Prince of Darkness (Satan)

References[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Milton, John (1674). Paradise Lost; A Poem in Twelve Books (II ed.). London: S. Simmons. Retrieved 8 January 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Paradise Lost: Introduction". Dartmouth College. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "John Milton". Poetry Foundation. 19 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Leonard 2000, p. xii.

- ^ Leonard 2000, p. xiii.

- ^ Broadbent 1972, p. 54.

- ^ Abrahm, M.H., Stephen Greenblatt, Eds. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. New York: Norton, 2000.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Forsythe, Neil (2002). The Satanic Epic. Princeton University.

- ^ Teskey, Gordon (2005). "Introduction". Paradise Lost: A Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton. pp. xxvii-xxviii. ISBN 978-0393924282.

- ^ History, Stephanie Pappas-Live Science Contributor 2019-09-16T18:16:12Z. "Secret Message Discovered in Milton's Epic 'Paradise Lost'". livescience.com. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ McCollom, William G. ―The Downfall of the Tragic Hero.‖ College English 19.2 (1957): 51- 56.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (Taha, Ibrahim. "Heroism in Literature." The American Journal of Semiotics18.1/4 (2002): 107-26. Philosophy Document Center. Web. 12 November 2014)

- ^ Taha, Ibrahim. "Heroism in Literature." The American Journal of Semiotics18.1/4 (2002): 107-26. Philosophy Document Center. Web. 12 November 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steadman, John M. "Heroic Virtue and the Divine Image in Paradise Lost. "Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 22.1/2 (1959): pp. 89

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steadman, John M. "Heroic Virtue and the Divine Image in Paradise Lost. "Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 22.1/2 (1959): pp. 90

- ^ Milton, John. Paradise Lost. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York ; London: W.W. Norton, 2012. 1950. Print.

- ^ Rebhorn, Wayne A. "The Humanist Tradition and Milton's Satan: The Conservative as Revolutionary." SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, Vol. 13, No. 1, The English Renaissance (Winter 1973), pp. 81-93. Print.

- ^ Marshall 1961, p. 17

- ^ Milton 1674 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMilton1674 (help), 12:310-314

- ^ Lehnhof 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Milton 1674 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMilton1674 (help), 4:42–43.

- ^ Lehnhof 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Van Nuis 2000, p. 50.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mikics 2004, p. 22 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMikics2004 (help).

- ^ Mikics, David (24 February 2004). "Miltonic Marriage and the Challenge to History in Paradise Lost". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 46 (1): 20–48. doi:10.1353/tsl.2004.0005. S2CID 161371845 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Biberman 1999, p. 137.

- ^ Milton 1674 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMilton1674 (help), Book 11.

- ^ Lyle 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harding 2007, p. 163.

- ^ Lyle 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Lyle 2000, p. 147.

- ^ Lewalski 2003, p. 223.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel. Lives of the English Poets. New York: Octagon, 1967.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Leonard, John. "Introduction." Paradise Lost. New York: Penguin, 2000.

- ^ Blake, William. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. 1793.

- ^ "John Rogers Milton". Yale. 19 February 2020.

- ^ Gregory 2006 p. 178

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gregory 2006 pp. 178–179

- ^ Quint 1993 pp. 325–326

- ^ Quint 1993 p. 340

- ^ Milton, John, Paradise Lost. Merritt Hughes, ed. New York, 1985

- ^ Greene 1989 p.27

- ^ Brisman 1973 pp. 7–8

- ^ Keats 1899 p. 408

- ^ Bate 1962 pp. 66–67

- ^ Illustrating Paradise Lost Archived 1 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine from Christ's College, Cambridge, has all twelve on line. See Medina's article for more on the authorship, and all the illustrations, which are also in Commons.

- ^ William Bridges Hunter (1978). A Milton encyclopedia. Bucknell University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8387-1837-7.

- ^ Lockport Street Gallery. Retrieved on 2013-12-13.

- ^ Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved on 2013-12-13.

- ^ WikiPaintings. Retrieved on 2013-12-13.

Bibliography[]

- Anderson, G (January 2000), "The Fall of Satan in the Thought of St. Ephrem and John Milton", Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, 3 (1), archived from the original on 26 February 2008

- Biberman, M (January 1999), "Milton, Marriage, and a Woman's Right to Divorce", SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, 39 (1): 131–153, doi:10.2307/1556309, JSTOR 1556309

- Black, J, ed. (March 2007), "Paradise Lost", The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, A (Concise ed.), Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, pp. 998–1061, ISBN 978-1-55111-868-0, OCLC 75811389

- Blake, W. (1793), , London.

- Blayney, B, ed. (1769), , Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Bradford, R (July 1992), Paradise Lost (1st ed.), Philadelphia: Open University Press, ISBN 978-0-335-09982-5, OCLC 25050319

- Broadbent, John (1972), Paradise Lost: Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521096393

- Butler, G (February 1998), "Giants and Fallen Angels in Dante and Milton: The Commedia and the Gigantomachy in Paradise Lost", Modern Philosophy, 95 (3): 352–363

- Carter, R. and McRae, J. (2001). The Routledge History of Literature in English: Britain and Ireland. 2 ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- Carey, J; Fowler, A (1971), The Poems of John Milton, London

- Doerksen, D (December 1997), "Let There Be Peace': Eve as Redemptive Peacemaker in Paradise Lost, Book X", Milton Quarterly, 32 (4): 124–130, doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1997.tb00499.x, S2CID 162488440

- Eliot, T.S. (1957), On Poetry and Poets, London: Faber and Faber

- Eliot, T. S. (1932), "Dante", Selected Essays, New York: Faber and Faber, OCLC 70714546.

- Empson, W (1965), Milton's God (Revised ed.), London

- John Milton: A Short Introduction (2002 ed., paperback by Roy C. Flannagan, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-22620-8; 2008 ed., ebook by Roy Flannagan, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-470-69287-5)

- Forsyth, N (2003), The Satanic Epic, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-11339-5

- Frye, N (1965), The Return of Eden: Five Essays on Milton's Epics, Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- Harding, P (January 2007), "Milton's Serpent and the Birth of Pagan Error", SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, 47 (1): 161–177, doi:10.1353/sel.2007.0003, S2CID 161758649

- Hill, G (1905), Lynch, Jack (ed.), Samuel Johnson: The Lives of the English Poets, 3 vols, Oxford: Clarendon, OCLC 69137084, archived from the original on 18 February 2012, retrieved 22 December 2006

- Kermode, F, ed. (1960), The Living Milton: Essays by Various Hands, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7100-1666-2, OCLC 17518893

- Kerrigan, W, ed. (2007), The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton, New York: Random House, ISBN 978-0-679-64253-4, OCLC 81940956

- (Summer 2004), "Paradise Lost and the Concept of Creation", South Central Review, 21 (2): 15–41, doi:10.1353/scr.2004.0021, S2CID 13244028

- Leonard, John (2000), "Introduction", in Milton, John (ed.), Paradise Lost, New York: Penguin, ISBN 9780140424393

- Lewalski, B. (January 2003), "Milton and Idolatry", SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, 43 (1): 213–232, doi:10.1353/sel.2003.0008, S2CID 170082234

- Lewis, C.S. (1942), A Preface to Paradise Lost, London: Oxford University Press, OCLC 822692

- Lyle, J (January 2000), "Architecture and Idolatry in Paradise Lost", SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, 40 (1): 139–155, doi:10.2307/1556158, JSTOR 1556158

- Marshall, W. H. (January 1961), "Paradise Lost: Felix Culpa and the Problem of Structure", Modern Language Notes, 76 (1): 15–20, doi:10.2307/3040476, JSTOR 3040476

- Mikics, D (2004), "Miltonic Marriage and the Challenge to History in Paradise Lost", Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 46 (1): 20–48, doi:10.1353/tsl.2004.0005, S2CID 161371845

- Miller, T.C., ed. (1997), The Critical Response to John Milton's "Paradise Lost", Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-28926-2, OCLC 35762631

- Milton, J (1674), (2nd ed.), London: S. Simmons

- Rajan, B (1947), Paradise Lost and the Seventeenth Century Reader, London: Chatto & Windus, OCLC 62931344

- Ricks, C.B. (1963), Milton's Grand Style, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 254429

- Stone, J.W. (May 1997), ""Man's effeminate s(lack)ness:" Androgyny and the Divided Unity of Adam and Eve", Milton Quarterly, 31 (2): 33–42, doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1997.tb00491.x, S2CID 163023289

- Van Nuis, H (May 2000), "Animated Eve Confronting Her Animus: A Jungian Approach to the Division of Labor Debate in Paradise Lost", Milton Quarterly, 34 (2): 48–56, doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.2000.tb00619.x

- Walker, Julia M. (1998), Medusa's Mirrors: Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, and the Metamorphosis of the Female Self, University of Delaware Press, ISBN 978-0-87413-625-8

- Wheat, L (2008), Philip Pullman's His dark materials—a multiple allegory : attacking religious superstition in The lion, the witch, and the wardrobe and Paradise lost, Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-59102-589-4, OCLC 152580912

Further reading[]

- Patrides, C. A. Approaches to Paradise Lost: The York Tercentenary Lectures (University of Toronto, 1968) ISBN 0-8020-1577-8

- Ryan J. Stark, "Paradise Lost as Incomplete Argument," 1650—1850: Aesthetics, Ideas, and Inquiries in the Early Modern Era (2011): 3–18.

External links[]

- Gustave Doré Paradise Lost Illustrations from the university at Buffalo Libraries

- Major Online Resources on Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Paradise Lost public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Online text[]

- Paradise Lost at Standard Ebooks

- Project Gutenberg text version 1

- Project Gutenberg text version 2

- Paradise Lost PDF/Ebook version with layout and fonts inspired by 17th century publications.

- paradiselost.org has the original poetry side by side with a translation to plain (prosaic) English

Other information[]

- darkness visible – comprehensive site for students and others new to Milton: contexts, plot and character summaries, reading suggestions, critical history, gallery of illustrations of Paradise Lost, and much more. By students at Milton's Cambridge college, Christ's College.

- Selected bibliography at the Milton Reading Room – includes background, biography, criticism.

- Paradise Lost learning guide, quotes, close readings, thematic analyses, character analyses, teacher resources

- 1667 books

- 1667 poems

- 1674 books

- Christian poetry

- Epic poems in English

- Poetry by John Milton

- Biblical paraphrases

- Biblical poetry

- Garden of Eden

- Cultural depictions of Adam and Eve

- Cosmogony

- God in fiction

- The Devil in fiction

- Lucifer

- Beelzebub

- Parallel literature