Partition of Bengal (1905)

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

|

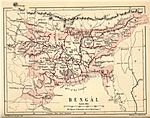

The first Partition of Bengal (1905) was a territorial reorganization of the Bengal Presidency implemented by the authorities of the British Raj. The reorganization separated the largely Muslim eastern areas from the largely Hindu western areas. Announced on 19 July 1905 by Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India, and implemented on 16 October 1905, it was undone a mere six years later.

The Hindus of West Bengal complained that the division would make them a minority in a province that would incorporate the province of Bihar and Orissa. Hindus were outraged at what they saw as a "divide and rule" policy,[1][2]: 248–249 even though Curzon stressed it would produce administrative efficiency. The partition animated the Muslims to form their own national organization along communal lines. To appease Bengali sentiment, Bengal was reunited by Lord Hardinge in 1911, in response to the Swadeshi movement's riots in protest against the policy.

Background[]

The Bengal Presidency encompassed Bengal, Bihar, parts of Chhattisgarh, Orissa, and Assam.[3]: 157 With a population of 78.5 million it was British India's largest province.[4]: 280 For decades British officials had maintained that the huge size created difficulties in effective management[3]: 156 [5]: 156 and had caused neglect of the poorer eastern region.[3]: 156–157 The idea of the partition had been brought up only for administrative reasons.[6]: 280 Therefore,[5]: 156 Curzon planned to split Orissa and Bihar and join fifteen eastern districts of Bengal with Assam. The eastern province held a population of 31 million, most of which was Muslim, with its centre at Dhaka.[3]: 157 Once the Partition was completed Curzon pointed out that he thought of the new province as Muslim.[6]: 280 Lord Curzon's intention was not specifically to divide Hindus from Muslims, but only to divide Bengalis.[7]: 148 The Western districts formed the other province with Orissa and Bihar.[6]: 280 The union of western Bengal with Orissa and Bihar reduced the speakers of the Bengali language to a minority.[4]: 280 Muslims led by the Nawab Sallimullah of Dhaka supported the partition and Hindus opposed it.[8]: 39

Partition[]

The English-educated middle class of Bengal saw this as a vivisection of their motherland as well as a tactic to diminish their authority.[5]: 156 In the six-month period before the partition was to be effected the Congress arranged meetings where petitions against the partition were collected and given to impassive authorities. Surendranath Banerjee had suggested that the non-Bengali states of Orissa and Bihar be separated from Bengal rather than dividing two parts of the Bengali-speaking community, but Lord Curzon did not agree to this.[9][better source needed] Banerjee admitted that the petitions were ineffective; as the date for the partition drew closer, he began advocating tougher approaches such as boycotting British goods. He preferred to label this move as swadeshi instead of a boycott.[4]: 280 The boycott was led by the moderates but minor rebel groups also sprouted under its cause.[5]: 157

Banerjee believed on that other targets ought to be included. Government schools were spurned and on 16 October 1905, the day of partition, schools and shops were blockaded. The demonstrators were cleared off by units of the police and army. This was followed by violent confrontations, due to which the older leadership in the Congress became anxious and convinced the younger Congress members to stop boycotting the schools. The president of the Congress, G.K. Gokhale, Banerji and others stopped supporting the boycott when they found that John Morley had been appointed as Secretary of State for India. Believing that he would sympathise with the Indian middle class they trusted him and anticipated the reversal of the partition through his intervention.[4]: 280

Political crisis[]

The partition triggered radical nationalism.

Nationalists all over India supported the Bengali cause, and were shocked at the British disregard for public opinion and what they perceived as a "divide and rule" policy. The protests spread to Bombay, Poona, and Punjab. Lord Curzon had believed that the Congress was no longer an effective force but provided it with a cause to rally the public around and gain fresh strength from.[5]: 157 The partition also caused embarrassment to the Indian National Congress.[6]: 289 Gokhale had earlier met prominent British liberals, hoping to obtain constitutional reforms for India.[6]: 289–290 The radicalization of Indian nationalism because of the partition would drastically lower the chances for the reforms. However, Gokhale successfully steered the more moderate approach in a Congress meeting and gained support for continuing talks with the government. In 1906 Gokhale again went to London to hold talks with Morley about the potential constitutional reforms. While the anticipation of the liberal nationalists increased in 1906 so did tensions in India. The moderates were challenged by the Congress meeting in Calcutta, which was in the middle of the radicalised Bengal.[6]: 290 The moderates countered this problem by bringing Dadabhai Naoroji to the meeting. He defended the moderates in the Calcutta session and thus the unity of the Congress was maintained. The 1907 Congress was to be held at Nagpur. The moderates were worried that the extremists would dominate the Nagpur session. The venue was shifted to the extremist free Surat. The resentful extremists flocked to the Surat meeting. There was an uproar and both factions held separate meetings. The extremists had Aurobindo and Tilak as leaders. They were isolated while the Congress was under the control of the moderates. The 1908 Congress Constitution formed the All-India Congress Committee, made up of elected members. Thronging the meetings would no longer work for the extremists.[6]: 291

Reunited Bengal (1911)[]

The authorities, not able to end the protests, assented to reversing the partition.[3]: 158 King George V announced at on 12 December 1911[10] that eastern Bengal would be assimilated into the Bengal Presidency.[11]: 203 Districts where Bengali was spoken were once again unified, and Assam, Bihar and Orissa were separated. The capital was shifted to New Delhi, clearly intended to provide the British colonial government with a stronger base.[3]: 158 Muslims of Bengal were shocked because they had seen the Muslim majority East Bengal as an indicator of the government's enthusiasm for protecting Muslim interests. They saw this as the government compromising Muslim interests for Hindu appeasement and administrative ease.[11]: 203

The partition had not initially been supported by Muslim leaders.[5]: 159 After the Muslim majority province of Eastern Bengal and Assam had been created prominent Muslims started seeing it as advantageous. Muslims, especially in Eastern Bengal, had been backward in the period of United Bengal. The Hindu protest against the partition was seen as interference in a Muslim province.[7]: 151 With the move of the capital to a Mughal site, the British tried to satisfy Bengali Muslims who were disappointed with losing hold of eastern Bengal.[12]

Aftermath[]

The uproar that had greeted Curzon's contentious move of splitting Bengal, as well as the emergence of the 'Extremist' faction in the Congress, became the final motive for separatist Muslim politics.[13]: 29 In 1909, separate elections were established for Muslims and Hindus. Before this, many members of both communities had advocated national solidarity of all Bengalis. With separate electorates, distinctive political communities developed, with their own political agendas. Muslims, too, dominated the Legislature, due to their overall numerical strength of roughly twenty two to twenty eight million. Muslims began to demand the creation of independent states for Muslims, where their interests would be protected.[14]: 184, 366

In 1947, Bengal was partitioned for the second time, solely on religious grounds, as part of the Partition of India following the formation of the nations India and Pakistan.[15] In 1947, East Bengal joined Pakistan (renamed to East Pakistan in 1955), and in 1971 became the independent state of Bangladesh.[14]: 366

See also[]

- West Bengal

- 1947 Partition of Bengal

Notes[]

- ^ "Indian history: Partition of Bengal". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Bipan Chandra (2009). History of Modern India. ISBN 978-81-250-3684-5.

- ^ a b c d e f David Ludden (2013). India and South Asia: a short history. Oneworld Publications.

- ^ a b c d Burton Stein (2010). A History of India (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

- ^ a b c d e f Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India (PDF) (4th ed.). Routledge.

- ^ a b Peter Hardy (1972). The Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- ^ Craig Baxter (1997). Bangladesh: from a nation to a state. WestviewPress. ISBN 978-0-8133-3632-9.

- ^ aurthor=Sachhidananda Banerjee;title=ISC History Class XI

- ^ https://ir.nbu.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/2707/13/13_chapter%201.pdf. Page-4

- ^ a b Francis Robinson (1974). Separatism Among Indian Muslims: The Politics of the United Provinces' Muslims, 1860–1923. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Stanley Wolpert. "Moderate and militant nationalism". India. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Ian Talbot; Gurharpal Singh (2009). The Partition of India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85661-4.

- ^ a b Judith M. Brown (1985). Modern India.

- ^ Haimanti Roy (November 2009). "Partition of Contingency? Public Discourse in Bengal, 1946–1947". Modern Asian Studies. 43 (6): 1355–1384.

Further reading[]

- Michael Edwardes (1965). High Noon of Empire: India under Curzon.

- John R. McLane (July 1965). "The Decision to Partition Bengal in 1905". Indian Economic and Social History Review. 2 (3): 221–237.

- Sufia Ahmed (2012). "Partition of Bengal, 1905". In Sirajul Islam; Ahmed A. Jamal (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- History of West Bengal

- History of Bangladesh

- History of Bengal

- Partition of India

- Partition (politics)

- 1905 in India