Paul Rée

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2013) |

Paul Rée | |

|---|---|

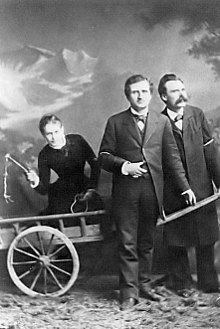

Lou Andreas-Salomé, Paul Rée and Friedrich Nietzsche (1882) | |

| Born | Paul Ludwig Carl Heinrich Rée 21 November 1849 |

| Died | 28 October 1901 (aged 51) Celerina, Switzerland |

| Cause of death | Falling into the Charnadüra Gorge |

| Occupation | Doctor |

Paul Ludwig Carl Heinrich Rée (21 November 1849 – 28 October 1901) was a German author, physician, philosopher, and friend of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Biography[]

Rée was born in Bartelshagen, Province of Pomerania, Prussia on the noble estate "Rittergut Adlig Bartelshagen am Grabow" near the south coast of the Baltic Sea. He was the third child of assimilated Jewish[1] parents, lord of the manor Ferdinand Philipp Rée from Hamburg and Jenny Julie Philippine Rée (née Jenny Emilie Julie Georgine Jonas).

In the history of ideas, he is primarily known as an auxiliary figure through his friendship with Friedrich Nietzsche, rather than as an important philosopher in his own right. Most of the general judgments of his character and work go back to formulations of Nietzsche and their mutual friend Lou Andreas-Salomé.

Rée's status as the son of a wealthy businessman and landowner allowed him to study philosophy and law at the University of Leipzig. The monthly allowance Rée received from his family allowed him to pursue his own interests in his studies. He had read Darwin, Schopenhauer, and French writers such as La Bruyère and La Rochefoucauld. Rée conglomerated his diverse studies under the heading of “psychological observations”, describing human nature through aphorisms, literary and philosophical exegesis. By 1875, Rée had qualified for his doctorate from Halle, and produced a dissertation on “the noble” in Aristotle’s Ethics.

Rée's book The Origin of the Moral Sensations largely was written in the autumn of 1877 in Sorrento, where Rée and Nietzsche both worked by invitation of Malwida von Meysenbug. The book sought to answer two questions. First, Rée attempted to explain the occurrence of altruistic feelings in human beings. Second, Rée tried to explain the interpretive process which denoted altruistic feelings as moral. Reiterating the conclusions of Psychological Observations, Rée claimed altruism was an innate human drive that over the course of centuries has been strengthened by selection.

Published in 1877, The Origin of the Moral Sensations was Rée's second book. His first was titled Psychological Observations. In The Origin of the Moral Sensations, Rée announced in the foreword that the book was inductive. He first observed the empirical phenomena he thought constituted man's moral nature and then looked into their origins. Rée proceeded from the premise that we feel some actions to be good and others evil. From the latter came the guilty conscience. Rée also followed many philosophers in rejecting free will. The error of free will, Rée claims, lies behind the development of the feeling of justice:

The feeling of justice thus arises out of two errors, namely, because the punishments inflicted by authorities and educators appear as acts of retribution, and because people believe in the freedom of the will.

— Paul Rée, The Origin of the Moral Sensations, ed. Robin Small, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003

Rée rejected metaphysical explanations of good and evil; he thought that the best explanations were those offered by Darwin and Lamarck, who had traced moral phenomena back to their natural causes. Rée argued that our moral sentiments were the result of changes that had occurred over the course of many generations. Like Lamarck, Rée argued that acquired habits could be passed to later generations as innate characteristics. As an acquired habit, altruistic behavior eventually became an innate characteristic. Altruistic behavior was so beneficial, Rée claimed, that it came to be praised unconditionally, as something good in itself, apart from its outcomes.

Nietzsche criticized Rée's The Origin of the Moral Sensations in the preface to On the Genealogy of Morals, writing that "Perhaps I have never read anything to which I would have said to myself No, proposition by proposition, conclusion by conclusion, to the extent that I did to this book; yet quite without ill-humour or impatience."[2]

Rée's friendship with Nietzsche disintegrated in the late Fall 1882 due to complications from their mutual involvement with Lou Salomé. Rée became a practicing physician.[3]

Rée died by falling into the while hiking in the Swiss Alps near Celerina on 28 October 1901.[4] His body was found the same day in the Inn River.[5] According to Nietzsche's biographer Rüdiger Safranski, Rée fell from a "slippery cliff," and it "is unclear whether it was an accident or suicide."[3] Rée had declared, not long before his death, "I have to philosophize. When I run out of material about which to philosophize, it is best for me to die."[6]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Beckman, Tad (1995). "The Case of Lou Salome". Harvey Mudd College. Archived from the original on 14 January 2003.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1969). On the Genealogy of Morals. Translated by Kaufmann, Walter. New York: Vintage. p. 18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Safranksi 2002, p. 182–3.

- ^ Ree, Paul; Small, Robin (1 October 2010). Basic Writings. University of Illinois Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780252092244.

- ^ Von der Lippe, Angela (10 November 2008). The Truth About Lou: A Novel After Salomé. Counterpoint Press. p. 127. ISBN 9781582436579.

- ^ Safranksi 2002, p. 183.

References[]

- Ludger Luetkehaus, Ein Heiliger Immoralist. Paul Rée (1849–1901). Biografischer Essay, Marburg: Basilisken Presse, 2001

- Ruth Stummann-Bowert (ed.), Malwida von Meysenbug-Paul Rée: Briefe an einen Freund, Würzburg: Könighausen und Neumann, 1998

- Safranksi, Rüdiger (2002). Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393323801.

- Hubert Treiber (ed.), Paul Rée: Gesammelte Werke, 1875–1885, Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter Verlag, 2004

External links[]

Quotations related to Paul Rée at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Paul Rée at Wikiquote

- 1849 births

- 1901 deaths

- 19th-century German Jews

- 19th-century German non-fiction writers

- 19th-century German philosophers

- 19th-century German physicians

- 19th-century essayists

- 19th-century physicians

- 20th-century essayists

- 20th-century German non-fiction writers

- 20th-century German philosophers

- 20th-century German physicians

- 20th-century physicians

- Accidental deaths from falls

- Aphorists

- Continental philosophers

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- German ethicists

- German male essayists

- German male writers

- German male non-fiction writers

- Jewish philosophers

- Moral philosophers

- People from the Province of Pomerania

- People from Vorpommern-Rügen

- Phenomenologists

- Philosophers of ethics and morality

- Philosophers of literature

- Philosophers of psychology

- Philosophers of science

- Philosophers of social science

- Philosophy writers

- Social critics

- Social philosophers

- Theorists on Western civilization

- Unsolved deaths

- Writers about activism and social change