Pausanias the Regent

| Pausanias | |

|---|---|

Bust of Pausanias, in the Capitoline Museums, Rome. | |

| Regent of Sparta | |

| Reign | 479–478 BC |

| Predecessor | Cleombrotus |

| Successor | Pleistarchus |

| Died | 477 BC Sparta |

| Issue |

|

| Greek | Παυσανίας |

| House | Agiad |

| Father | Cleombrotus |

| Mother | Theano |

Pausanias (Greek: Παυσανίας; died c. 477 BC [1]) was a Spartan regent and a general who succeeded his father Cleombrotus who, in turn, succeeded king Leonidas I. In 479 BC, as a leader of the Hellenic League's combined land forces, Pausanias won a pivotal victory in the Battle of Plataea ending the Second Persian invasion of Greece. One year after the victories over Persians and Persian allies, Pausanias fell under suspicion of conspiring with the Persian king, Xerxes I to betray Greeks and died in 477 BC in Sparta starved to death by fellow citizens. What is known of his life is largely according to Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, Diodorus' Bibliotheca historica and a handful of other classical sources.

Early life[]

Pausanias like all Spartan citizens (Spartiate), would have gone through the intense training from his early childhood at the age of seven and be a regular soldier until the age of thirty. Pausanias was from the royal house Agiads, and even with royal blood and belonging to the one of the royal families that did not exempt him from going through the same training as every other citizen. As every male Spartan citizen earned their citizenship by dedicating their lives to their polis and its laws.[2]

Spartan lineage[]

As a son of the regent Cleombrotus and a nephew of the recently deceased warrior king, Leonidas I, Pausanias was a scion of the Spartan royal house of the Agiads, but not in the direct line of succession as he was not the first born son of one of the Kings of Sparta. After Leonidas' death, while the king's son Pleistarchus was still in his minority, Pausanias served as regent of Sparta. Pausanias was also the father of Pleistoanax who later became king. Pausanias' other sons were Cleomenes and Nasteria.

War service[]

Pausanias was leader of the Spartan army alongside Euryanax son of Dorieus, as the King of Sparta Pleistarchos son of Leonidas I was too young to command. Pausanias led 5000 Spartans to the aid of the created to resist the Persian invasion.[3] At the Hellenes encampment at Platea 110,000 men were assembled along the Asopos River, and further down the river Mardonius, commander of the Persian forces stationed 300,000 Persian forces along side potentially 50,000 Greek allies.[4] After eleven days of both sides not making the first move, and Mardonius finding out that Pausanias had ordered the Spartans and Athenians to switch ranks to counter the most favorable opponent Mardonius offered a challenge that was refused with no answer.[5] With no answer to the challenge Mardonius ordered his cavalry to pollute the Asopos from which the Hellenes get their water, so they decide in the night to head to Platea.[6] The forces led by Pausanias headed through the ridges and foothills of the Cithaeron while the Athenian forces headed the opposite direction into the Plains.[7] Mardonius believes the Hellenes are fleeing, so with no formation in mind he sends his military to charge after Pausanias and sends a dispatch of Hellene Greek allies after the Athenians.[8] With the battle commencing Pausanias sends a messenger to ask for Athenian aid, but they cannot send any, so Pausanias with 50,000 Lacedaemonians and 3,000 Tegeans prepared for battle at Platea.[9] Pausanias led the Greeks to victory over the Persians and Persian allies led by Mardonius at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC.[10] While the Battle of Plataea is sometimes seen as a chaotic battle,[11] others see evidence of both strategic and tactical skill on the part of Pausanias in delaying the engagement until the point where Spartan arms and discipline could have maximum impact.[12] Herodotus concluded that "Pausanias the son of Cleombrotus and grandson of Anaxandridas won the most glorious victory of any known to us".[13]

After the victories at Plataea and the Battle of Mycale, the Spartans lost interest in liberating the Greek cities of Asia Minor until it became clear that Athens would dominate the League in Sparta's absence. Sparta then sent Pausanias back to command the Greek military.

Suspected pact with Persia[]

In 478 BC, Pausanias was accused of conspiring with the Persians and recalled to Sparta. One allegation was that after capturing Cyprus and Byzantium Pausanias released some of the prisoners of war who were friends and relatives of the king of Persia. Pausanias argued that the prisoners simply escaped. Another allegation was that Pausanias sent a letter via Gongylos of Eretria (Diodorus has general Artabazos I of Phrygia as a mediator) to Xerxes I saying he wished to help Xerxes and bring Sparta with the rest of Greece under Persian control. In return, Pausanias wished to marry Xerxes's daughter. After Xerxes replied agreeing to his plans, Pausanias started to adopt Persian customs and dress like a Persian aristocrat. Due to lack of evidence, Pausanias was acquitted and left Sparta on his own accord, taking a trireme from the town of Hermione.[14]

According to Thucydides and Plutarch[15] Athenians and many Hellenic League allies were displeased with Pausanias because of Pausanias' arrogance and high-handedness.

In 477 BC, the Spartans recalled Pausanias once again. Pausanias went to Kolonai in the Troad before returning to Sparta. Upon arrival to Sparta, the ephors imprisoned, but later released Pausanias. At first, nobody had enough evidence to convict Pausanias of disloyalty, even though some helots reported that Pausanias offered freedom if helots joined in revolt. Later, one of the messengers Pausanias used to communicate with Persians provided written evidence (a letter stating Pausanias' intentions) to Spartan ephors.[16]

Diodorus adds further detail to Thucydides' account. After ephors were loath to believe the letter provided by the messenger, the messenger offered to produce Pausanias' acknowledgement in person. In the letter Pausanias asked Persians to kill the messenger. The messenger and the ephors went to the Temple of Poseidon (Tainaron). Ephors concealed themselves in a tent at the shrine and the messenger waited for Pausanias. When Pausanias arrived, the messenger confronted Pausanias asking why did the letter say to kill whoever delivered the letter. Pausanias said that he was sorry and asked the messenger to forgive the mistake. Pausanias offered gifts to the messenger. Ephors heard the conversation from the tent.[17]

Herodotus notes that Athenians were hostile to Pausanias and wished Pausanias removed from Greek command,[18] with his Athenian counterpart Themistocles publicly ostracizing him as a threat to democracy. A. R. Burn speculates that Spartans became concerned with Pausanias' innovatory views on freeing the Helots.[19]

Death[]

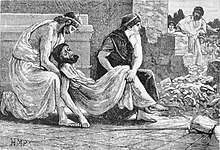

According to Thucydides, Diodorus and Polyaenus, pursued by ephors, Pausanias took refuge in the temple of Athena "of the Brazen House" (Χαλκίοικος, Chalkioikos) (located in the acropolis of Sparta). Pausanias' mother Theano (Ancient Greek: Θεανὼ) immediately went to the temple, and laid a brick at the door saying: "Unworthy to be a Spartan, you are not my son", (According to 1.1). Following the mother's example, the Spartans blocked the doorway with bricks and forced Pausanias to die of starvation. After Pausanias' body was turned over to relatives for burial, the divinity through the Oracle of Delphi showed displeasure at the violation of the sanctity of suppliants. The oracle said that Athena demanded return of the suppliant. Unable to carry out the injunction of the goddess, the Spartans set up two bronze statues of Pausanias at the temple of Athena. [20] [21] [22]

Legacy[]

Pausanias is a central figure in the "Pausanias, the betrayer of his country a tragedy, acted at the Theatre Royal by His Majesties servants" by Richard Norton and Thomas Southerne.[23]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Diodorus XI. 41

- ^ "Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaimonians, chapter 4, section 6". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories 9.10.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories 9.29-9.32.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories 9.40-9.48.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories 9.49-9.51.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories 9.56.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories 9.58-9.59.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories 9.60-9.61.

- ^ Herodotus, Historia 9

- ^ J Boardman ed., The Oxford History of the Classical World (Oxford 1991) p. 48

- ^ A R Burn, Persia and the Greeks (Stanford 1984) pp. 533–39

- ^ R Waterfield trans, Herodotus: The Histories (Oxford 2008) p. 567

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponesian War 1.128–130

- ^ Plutarch, Cimon 6 and Aristeides 23

- ^ Thucydides I.133 s:History of the Peloponnesian War/Book 1#Second Congress at Lacedaemon - Preparations for War and Diplomatic Skirmishes - Cylon - Pausanias - Themistocles

- ^ Diodorus XI. 45

- ^ R Waterfield trans, Herodotus: The Histories (Oxford 2008) p. 731

- ^ A R Burn, Persia and the Greeks (Stanford 1984) pp. 543, 565

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponesian War 1.134

- ^ Diodorus XI. 45

- ^ Polyaenus, Strategems, § 8.51.1

- ^ "Pausanias, the betrayer of his country a tragedy, acted at the Theatre Royal by His Majesties servants"

External links[]

- Ancient Spartan generals

- Rulers of Sparta

- 5th-century BC Spartans

- Spartans of the Greco-Persian Wars

- Deaths by starvation

- Medism

- Battle of Plataea

- 477 BC deaths

- Regents

- Agiad dynasty