Pedro Menéndez Márquez

Pedro Menéndez Márquez | |

|---|---|

| 3rd Governor of La Florida | |

| In office 1577 – 9 July 1594[1] | |

| Lieutenant | Vicente González and Tomás Bernaldo de Quirós |

| Preceded by | Gutierre de Miranda |

| Succeeded by | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c.1537[2] Asturias, Spain |

| Died | 1600 Florida |

| Spouse(s) | María de Miranda |

| Profession | explorer, conquistador and governor |

Pedro Menéndez Márquez (c.1537 – 1600) was a Spanish military officer, conquistador, and governor of Spanish Florida. He was a nephew of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who had been appointed adelantado (an elite military and administrative position) of La Florida by King Philip II. Márquez was also related to Diego de Velasco, Hernando de Miranda, Gutierre de Miranda,[3] Juan Menéndez Márquez, and Francisco Menéndez Márquez, all of whom served as governors of La Florida.

Early career[]

Pedro Menéndez Márquez was the son of Marquis Alonso ("El Mozo") and Maria Alonso Arango ("La Moza"). He had four siblings: Alonso, Juan, Catalina and Elvira Menéndez Marqués.[4] Márquez began serving with his uncle Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in about 1548, occasionally as master of ships under his uncle's command. As Pedro Menéndez de Avilés was preparing his expedition to found a colony in Florida, he appointed Márquez as second-in-command of the fleet sailing from Asturias. After the founding of St. Augustine and the expulsion of the French from Fort Caroline, Márquez was dispatched to carry the official report to Spain, in command of the ships returning there for supplies. Although Márquez was not the first to bring news of Menéndez de Avilés' success to King Phillip II, the king nevertheless awarded him 300 gold ducats. Márquez then loaded supplies for the new colony and sailed for Florida, but other ships in Menéndez de Avilés' fleet were prevented from leaving Spain.[5]

Governor of Cuba and Florida[]

For a brief period around 1571, Menéndez Marquéz served as lieutenant governor of Cuba under Menéndez de Avilés, who was then governor of Cuba, but usually absent from the island.[6][7] In 1573, he explored the Atlantic coast as far north as Chesapeake Bay.[8][9][10] In 1575, he brought nine Franciscan friars to Florida, the first in the colony[11]

In 1577, Philip II appointed Pedro Menéndez Márquez as governor of La Florida.[1][12] In October 1577, Márquez replaced Hernando de Miranda as governor of Santa Elena, located on what is now called Parris Island in Port Royal Sound, and reoccupied the settlement with a military force under his command. Márquez, anticipating that the Indians might attack any Spaniards who tried to return to Santa Elena, brought a prefabricated fort from St. Augustine and with 53 men erected it in just six days.[13]

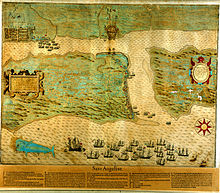

Menéndez Márquez successfully suppressed a rebellion of the Guale Indians provoked by his predecessor and restored or strengthened the Spanish outposts. He also had to deal with new French attempts to establish themselves along the coast north of Santa Elena, English raiding in the Caribbean, and the establishment of an English colony at Roanoke. When Sir Francis Drake attacked and burned St. Augustine and its fort on June 6–8, 1586[14][15] Marquéz had already ordered the evacuation of the city after a ship brought news from Hispaniola that Drake was in the Caribbean.[16] These factors combined with the failure to find the English colony at Roanoke caused Márquez to abandon the Spanish colony at Santa Elena and concentrate on reinforcing and rebuilding St. Augustine.[15] Márquez ordered his soldiers to build a new wooden fort to defend the city, and brought the settlers of the failed colony to the capital of La Florida.[17]

In 1580, Márquez discovered coquina, a sedimentary rock composed mostly of the ancient shells of small mollusks and later used in many buildings in St. Augustine, on Anastasia Island.[18] In 1587, he returned to Santa Elena and ordered his soldiers to destroy what remained of the Spanish infrastructure and the second Fort San Marcos.[17]

Although by 1589 Márquez knew that the English colony at Roanoke was gone, he planned on establishing a Spanish outpost on Chesapeake Bay to block future English settlements in the area. Instead, he was appointed to organize the treasure fleets in Havana, and did not return to Florida.[15]

Personal life[]

Pedro Menéndez Márquez married María de Miranda, according to the will of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés.[19]

Márquez arranged for his nephew, Juan Menéndez Márquez, to marry his niece, María Menéndez de Posada. Juan became the royal treasurer for Spanish Florida, and the couple's descendants remained prominent in official and economic affairs there for more than a century.[20]

According to Márquez, when he governed Florida he got half his salary through the situado (the Spanish Crown's royal subsidy of the colony) and the other half from the fruit he grew and sold. According to Domingo González de León, however, Marquez used the excuse that he got money from selling fruit to take money from the treasury whenever he wanted. Márquez and his nephew also were reported to have behaved strangely and improperly with the town's women, reportedly driving married women from their homes and forcing them to participate in mock military musters, as well as taking other women on picnics to a deserted island, and using them as they wished.[3]

Citations[]

- ^ a b U.S. States F-K.

- ^ "1593". University of Florida Digital Collections. John B. Stetson Card Calendar. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Karen Paar (1999). "Witness to Empire and the Tightening of Military Control: Santa Elena's Second Spanish Occupation, 1577-1587". University of North Carolina. Archived from the original (PhD. dissertation) on July 12, 2015.

- ^ Aviles. Familia del adelantado Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (In Spanish) Aviles. "The Family of Adelantado Pedro Menendez de Aviles".

- ^ Lyon: 73, 88, 144-145, 161n1, 163-164

- ^ El Explorador. Periódico Digital Espeleológico (In Spanish). "The Explorer. Digital Newspaper Speleological).

- ^ Willis Fletcher Johnson (1920). The History of Cuba (Complete). Library of Alexandria. ISBN 978-1-4655-1428-8.

- ^ Amy Waters Yarsinske (2002). Virginia Beach: A History of Virginia's Golden Shore. Arcadia Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7385-2402-3.

- ^ John Edwin Bakeless (1950). The eyes of discovery: the pageant of North America as seen by the first explorers. Lippincott. p. 227.

- ^ U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (1885). Annual Report of the Director. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 504.

Of the expeditions of Menendez the most interesting is recorded in the narrative by his nephew, Pedro Menendez Marquez, who was an able seaman and afterwards a commander of Spanish fleets. The nephew was accompanied by four ships and one hundred and fifty men. Barcia states that the exploration commenced at Cape Florida and was prosecuted northward beyond the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. This bay (says Barcia) is 3 leagues broad at its entrance and it stretches towards the north-northwest, and has many rivers and ports on both sides. His mention of soundings agrees so well with our charts that he must be regarded as one of the best amongst early explorers of Chesapeake Bay

- ^ David Arias (9 October 2009). The First Catholics of the United States. Lulu.com. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-557-07527-0.

- ^ María Antonia Sáinz Sastre (1992). Florida in the XVIth Century: Discovery and Conquest. Editorial MAPFRE. p. 266. ISBN 978-84-7100-473-4.

- ^ Chester B. DePratter (2005). "Santa Elena History: The Second Spanish Occupation: 1577 - 1587". South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology (SCIAA). University of South Carolina. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012.

- ^ Spencer Tucker (21 November 2012). Almanac of American Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3.

- ^ a b c Margaret F. Pickett; Dwayne W. Pickett (8 February 2011). The European Struggle to Settle North America: Colonizing Attempts by England, France and Spain, 1521-1608. McFarland. pp. 94–95, 202–204. ISBN 978-0-7864-6221-6.

- ^ Karen Ordahl Kupperman (30 June 2009). The Jamestown Project. Harvard University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-674-02702-2.

- ^ a b "Charlesfort-Santa Elena Port Royal, South Carolina". American Latino Heritage. National Park Service. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015.

- ^ "Long-Sanchez House HABS No. FIA-132 43" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey. National Park Service. 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 20, 2015.

(letter to King from Governor Pedro Menendez Marquez, December 27, 1583

- ^ Jeannette M. Connor (1925). Colonial Records of Spanish Florida: Letters and Reports of Governors, Deliberations of the Council of the Indies, Royal Decrees, and Other Documents. The Florida State Historical Society. p. xxiv.

- ^ Bushnell:118, 120

References[]

- Bushnell, Amy Turner (1991). "Thomas Menéndez Márquez: Criolla, Cattleman, and Contador/Tomás Menéndez Márquez: Criolla, Ganadero y Contador Real". In Ann L. Henderson and Gary L. Mormino (ed.). Spanish Pathways in Florida/Caminos Españoles en La Florida. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. pp. 118–139. ISBN 1-56164-003-4.

- Lyon, Eugene (1976). The Enterprise of Florida: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and the Spanish Conquest of 1565-1568 (Second (1990) paperkack ed.). Gainesville, Florida: The University Presses of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-0777-1.

- Pickett, Margaret F.; Dwayne W. Pickett (2011). The European Struggle to Settle North America: Colonizing Attempts by England, France and Spain, 1521 to 1608. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-5932-2.

- Spanish explorers

- Spanish explorers of North America

- Spanish conquistadors

- Royal Governors of La Florida

- Governors of Cuba

- Spanish colonial governors and administrators

- Explorers of the United States

- Explorers of Florida

- 1499 births