Peruonto

| Peruonto | |

|---|---|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Peruonto |

| Data | |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 675 (The Lazy Boy) |

| Region | Italy |

| Published in | Pentamerone, by Giambattista Basile |

| Related | At the Pike's Behest The Dolphin Half-Man Foolish Hans (de) Peter the Fool (fr) |

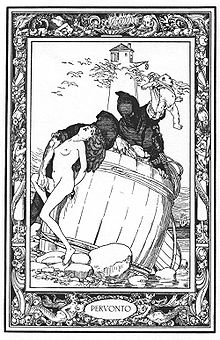

Peruonto is an Italian literary fairy tale written by Giambattista Basile in his 1634 work, the Pentamerone.[1]

Synopsis[]

A widow named Ceccarella had a stupid son named Peruonto, as ugly as an ogre. One day, she sent him to gather wood. He saw three men sleeping in the sunlight and made them a shelter of branches. They woke, and being the sons of a fairy, gave him a charm that whatever he asked for would be done. As he was carrying the wood back, he wished that it would carry him, and he rode it back like a horse. The king's daughter Vastolla, who never laughed, saw it and burst out laughing. Peruonto wished she would marry him and he would cure her of her laughing.

A marriage was arranged for Vastolla with a prince, but Vastolla refused, because she would marry only the man who rode the wood. The king proposed putting her to death. His councilors advised him to go after the man instead. The king had a banquet with all the nobles and lords, thinking Vastolla would betray which man it was, but she did not recognize any of them. The king would have put her to death at once, but the councillors advised a banquet for those still lower in birth. Peruonto's mother urged him to go, he went, and Vastolla recognized him at once and exclaimed. The king had her and Peruonto shut up in a cask and thrown into the sea. Vastolla wormed the story out of Peruonto, and told him to turn the cask to a ship. Then she had him turn it to a castle, and then she had him turn himself into a handsome and well-mannered man. They married and lived happily for years.

Her father grew old and sad. His councillors encouraged him to hunt to cheer him up. One day, he came to a castle and found only two little boys who welcomed him and brought him to a magical banquet. In the morning, he wished to thank them, but not only the boys but their mother and father—Vastolla and Peruonto—appeared. They were reconciled, and the king brought them back to his castle where the feast of celebration lasted nine days.

Analysis[]

Peruonto is classified as Aarne-Thompson type 675, "The Lazy Boy".[2]

Mythological parallels[]

Austrian consul and folktale collector Johann Georg von Hahn saw a parallel between the miraculous birth of the princess's child and their banishment to the sea in a casket and the Greek legend of Danae and her son, the hero Perseus.[3] A similar, yet unique ("found nowhere else in Greece") story is narrated by geographer Pausanias in his Description of Greece:[4] after giving birth to her semi-divine son, Dionysus, fathered by Zeus, human princess Semele was banished from the realm by her father Cadmus. Their sentence was to be put into a chest or a box (larnax) and cast in the sea. Luckily, the casket they were in washed up by the waves at Prasiae.[5][6][7] However, it has been suggested that this tale might have been a borrowing from the story of Danaë and Perseus.[8][9]

Another parallel lies in the legend of Breton saint Budoc and his mother Azénor: Azénor was still pregnant when cast into the sea in a box by her husband, but an angel led her to safety and she gave birth to future Breton saint Budoc.[10]

The "half-man" hero[]

Professors Michael Meraklis and Nicole Belmont remarked that, in some Greek and French variants of the tale type, the hero is a half-man son, born due to a hasty wish from his mother. At the end of the tale, the hero assumes a complete human body after he wishes to become a handsome nobleman.[11][12]

Variants[]

The tale type of ATU 675 is "told all over Europe"[13] and, argued Stith Thompson, "disseminated rather evenly" over the continent.[14] While noticing its dissemination throughout Europe, Paul Delarue stated that the tale type can be found in Turkey, and "here and there in the rest of Asia" (including Vietnam).[15]

19th century Portuguese folklorist Consiglieri Pedroso claimed that the tale type is "popular everywhere", but specially "in the East of Europe".[16] This seemed to be confirmed by Jack Haney, who observed that the tale is "common throughout the Eastern Slavic world".[17]

Historian William Reginald Halliday suggested an origin in Middle East, instead of Western Europe,[18] since the Half-Man or Half-Boy hero appears in Persian tales.[19]

Literary variants[]

Other European literary tales of the tale type are Straparola's "Peter The Fool" (Night Three, Fable One)[20] and Madame d'Aulnoy's The Dolphin.[21]

Distribution[]

Europe[]

Ireland[]

In an Irish variant collected in Bealoideas, a leprechaun is the magical creature that grants the wishes to a half-wit hero.[22]

France[]

A folk variant of the tale type is the French Half-Man.[23]

In a Breton language variant, Kristoff, the narrative environment involves the legendary Breton city of Ys.[24]

In a variant from Albret (Labrit), Bernanouéillo ("Bernanoueille"), collected by abbot Leopold Dardy, the donor who offers the protagonist the power to fulfill his wishes is "Le Bon Dieu" (God).[25]

Southern Europe[]

In the Portuguese variant The Baker's Idle Son, the pike that blesses the fool with the magical spell becomes a man and marries the princess.[26]

In a Greek variant collected by Johann Georg von Hahn, Der halbe Mensch ("The Half-Man"), the protagonist, a man born with only half of his body, wishes for the princess to be magically impregnated. After the recognition test by the child and the banishment of the family on the barrel, the princess marries a man of her father's court, and the half-man another woman.[27]

At least one variant from Cyprus has been published, from the "Folklore Archive of the Cyprus Research Centre".[28]

Italy[]

In a variant collected by Sicilian writer Giuseppe Pitre, Lu Loccu di li Pàssuli e Ficu ("The Fig-and-Raisin Fool"), the foolish character's favorite fruits are figs and raisins. He gains his wish-fulfilling ability after an encounter with some nymphs in the woods.[29]

French author Edouard Laboulaye published a "Neapolitan fairy tale" titled Zerbin le farouche, variously translated as "Zerbino the Bumpkin",[30] "Zerbino the Savage"[31] and "Zerbin the Wood-cutter".[32] In this variant, Zerbino is a lazy woodcutter from Salerno who earns his living by gathering firewood and selling, and spends the rest of his time sleeping. One day, in the woods, he creates shade for a mysterious woman that was resting and kills a snake. The woman, in return, reveals herself to be a fairy and tries to repay his kindness, but he refuses by saying he has what he wants. So the fairy grants him the power to make his wishes come true, and disappears into the lake. Zerbino awakes, cuts some wood and gathers them into a bundle. Unawares of his newfound magic, he wishes the bundle to carry him home. On their way, the taciturn princess of Salerno, Leila, sees the bizarre sight and explodes into laughter. Zerbino sees her and wishes her to fall in love with someone, and she becomes enamoured by Zerbino. Later, the king summons his minister Mistigris to find the man his daughter has fallen in love with. After Zerbino is brought to court, he and Leila are married and put on a boat along with Mistigris, to an unknown destiny. While adrift at sea, the fool Zerbino asks Mistigris to be fed figs and raisins.

Another Italian variant was collected from a 62-year-old farmer, Mariucca Rossi, in 1968. In this variant, titled Bertoldino, poor and foolish Bertoldino helps a fairy, is rewarded with the wish-granting ability, and the royal test with the princess's boy involves golden straw, instead of an apple or a ball.[33]

A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage"), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found sixteen variants of the tale across Italian sources, under the name Il Ragazzo Indolente.[34]

Germany[]

In a German variant by Adalbert Kuhn, Der dumme Michel, after the princess becomes pregnant and gives birth to the boy, the king's grandson insists that, in order to find his father, the king should invite every male in the kingdom, from the upper to the lower classes.[35]

Denmark[]

Danish variants are attested in the collections of Svend Grundtvig (Onskerne; "The Wishes")[36] and of Jens Kamp (Doven Lars, der fik Prinsessen; "Lazy Lars, who won a Princess").[37]

In another variant by Grundtvig, Den dovne Dreng ("The Idle Youth"), the titular protagonist releases a frog into the water, which blesses him with unlimited wishes.[38]

Finland[]

The tale type is noted to be "most frequently [collected]" in Finland.[39] In fact, it is reported to be one of the fifteen most popular tales in Finnish tradition, wih 168 variants.[40]

Estonia[]

Professor Oskar Loorits stated that the ATU 675 tale type is one of the favorite types ("sehr beliebt") in Estonia.[41]

Bulgaria[]

In the Bulgarian tale Der Faulpelz, oder: Gutes wird mit Gutem vergolten ("Lazybones, or: Good is repaid with good"), the lazy youth puts a fish back in the ocean and in return is taught a spell that can make all his wishes come true ("lengo i save i more"). When he passes by the tsar's palace, he commands the princess to be pregnant. In this variant, it is the princess herself who identifies the father of her child.[42] The tale was originally collected by Bulgarian folklorist Kuzman Shapkarev with the title Лèнго - ленѝвото дèте или доброто со добро се изплашчат ("Lengo, the Lazy Child or Good with Good is Repaid") and sourced as from Ohrid, modern day North Macedonia.[43]

Romania[]

In a Romanian variant, Csuka hírivel, aranyhal szerencséjivel ("Pike News, Goldfish Fortune"), collected from storyteller Károly Kovács,[44] the protagonist is a gypsy (Romani) youth who captures a goldfish and, in releasing him, learns the magic spell to make his wishes come true. When he is sunbathing near his shack, the princess passes by and, by his wish, becomes pregnant.[45]

Poland[]

A collection of Upper Silesian fairy tales by Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (unpublished at the time, but in print only later by his descendant Karl von Eichendorff (de)) contains a fragmentary version of the tale type, with the name Der Faulpelz und der Fisch ("The Lazy Boy and the Fish") or Das Märchen von dem Faulpelz, dem wunderbaren Fisch und der Prinzessin ("The Tale of the Lazy Boy, the Wonderful Fish and the Princess"). Scholarship suggests its origin to be legitimately Slavic, since the main character sleeps by the stove and eats cabbage soup, elements present in Russian and Polish variants.[46]

Americas[]

Scholars Richard Dorson and William Bernard McCarthy reported that the tale type was "well documented" in Hispanic- (Iberian) and Franco-American traditions,[47][48] and also existed in the West Indies and among the Native Americans.[49]

In a French-Missouri variant collected by scholar Joseph Médard Carrière, Pieds Sales ("Dirty Feet"), poor woodcutter Pieds Sales shares his food with a fairy and receives in return a magic wand that can grant all his wishes. He uses the wand to command the logs to carry him home. This strange vision prompts a surge of laughter in the princess. He uses the wand to make her magically pregnant. After the king finds the father of his grandson, he banishes the family on a barrel to the sea.[50]

In Argentinian variants, the main character, John the Lazy, receives a "virtue wand" from the magical fish to fulfill his wishes.[51]

Asia[]

In an Annamite tale, La fortune d'un paresseux ("The luck of a lazy one"), a lazy youth catches a fish. Because he is so lazy, he decided to wash the fish's scales with his urine. A crow steals it and drops it in the king's garden. The princess sees the fish and decides to cook it. She becomes pregnant and gives birth to a son. Her father, the king, throws her in prison and decides to summon all men in the kingdom. The lazy youth, as he passes by the king's palace in his small boat, is seen by the princess's son, who calls him his father.[52]

In a tale from "Tjames" (Champa), Tabong le Paresseux ("Tabong, the Lazy"), collected by Antony Landes, Tabong is a incredibly lazy youth. He catches two fishes, which are stolen by a raven. He gets a third fish and urinates on it, and lets the raven steal it. The raven drops the fish on a basin where the king's daughters are bathing. The youngest daughter takes the fish and brings to the palace to eat it. She becomes pregnant. Her father, the king, orders her to make a napkin of betel leaves and to summon all men in the kingdom. She is to throw the napkin in front of the assemblage, and it will indicate the father. The king finds out about him and orders the execution of both his daughter and Tabong, but the executioners spare their lives. The couple take residence on the mountainhills. One day, the vulture king sees Tabong lying down and, thinking him dead, flies down to eat him, but the youth catches the bird. The bird gives him a magical stone to the youth.[53] Folklorists Johannes Bolte and Jiri Polivka, in their commentaries to the Grimm Brothers fairy tales, listed this tale as a variant of German Dumm Hans ("Foolish Hans") and, by extension, of tale type 675.[54]

Adaptations[]

The tale served as basis for the opus Pervonte oder Die Wünschen ("Pervonte, or the Wishes") (de), by German poet Christoph Martin Wieland.[55]

A Hungarian variant of the tale type was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék ("Hungarian Folk Tales") (hu), with the title A rest legényröl ("The Lazy Boy").

See also[]

- Golden Goose

- The Magic Swan

- The Princess Who Never Smiled

- The Pink

- The Tale of Tsar Saltan (mother and son cast into the sea in a barrel)

- The Fisherman and His Wife (German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm)

- The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Alexander Pushkin's fairy tale in verse)

References[]

- ^ "Peruonto: Giambattista Basile's Il Pentamerone (Story of Stories) 1911 Version". SurLaLune Fairy Tales. 2002-11-01. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ [1] Archived April 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1-2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller, 1918. pp. 327-328.

- ^ Beaulieu, Marie-Claire. "The Floating Chest: Maidens, Marriage, and the Sea". In: The Sea in the Greek Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. pp. 97-98. Accessed May 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt17xx5hc.7.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. 3.24.3. -4.

- ^ Larson, Jennifer. Greek Heroine Cults. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995. pp. 94-95.

- ^ Holley, N. M. “The Floating Chest”. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 69 (1949): 39–40. doi:10.2307/629461.

- ^ Larson, Jennifer. Greek Heroine Cults. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995. p. 95.

- ^ Guettel Cole, Susan. "Under the Open Sky: Imagining the Dionysian Landscape". In: Human Development in Sacred Landscapes: Between Ritual Tradition, Creativity and Emotionality. V&R Unipress. 2015. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-7370-0252-3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737002523.61

- ^ Milin, Gaël (1990). "La légende bretonne de Saint Azénor et les variantes medievales du conte de la femme calomniée: elements pour une archeologie du motif du bateau sans voiles et sans rames". In: Memoires de la Societé d'Histoire et d'Archeologie de Bretagne 67. pp. 303-320.

- ^ Merakles, Michales G. Studien zum griechischen Märchen. Eingeleitet, übers, und bearb. von Walter Puchner. (Raabser Märchen-Reihe, Bd. 9. Wien: Österr. Museum für Volkskunde, 1992. p. 159. ISBN 3-900359-52-0.

- ^ Belmont, Nicole. (2005). "Half-Man in Folktales. Places, Uses and Meaning of a Special Motive". In: L'Homme no 174(2), 11-22. https://doi.org/10.4000/lhomme.25059

- ^ Belmont, Nicole (2005). Half-Man in Folktales. Places, Uses and Meaning of a Special Motive.. L'Homme, no 174(2): 11. https://doi.org/10.4000/lhomme.25059

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 68. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Delarue, Paul Delarue. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 389.

- ^ Pedroso, Consiglieri. Portuguese Folk-Tales. London: Published for the Folk-Lore Society. 1882. pp. vii.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 - Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2019 [2001]. p. 437. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ Dov Neuman (Noy). "Reviewed Work: Typen Tuerkischer Volksmaerchen by Wolfram Eberhard, Pertev Naili Boratav". In: Midwest Folklore 4, no. 4 (1954): 259. Accessed April 12, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4317494.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard McGillivray. Modern Greek folktales. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1953. p. 20.

- ^ "Pietro the Fool and the Magic Fish." In: The Pleasant Nights - Volume 1, edited by Beecher Donald, by Waters W.G., 367-86. Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto Press, 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442699519.19.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 100, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Hares-Stryker, Carolyn (1993). “Adrift on the Seven Seas: The Mediaeval Topos of Exile at Sea”. In: Florilegium 12 (June): 83. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/flor/article/view/19322.

- ^ Paul Delarue. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1956. p. 389-90.

- ^ Boyd, Matthieu. "What’s New in Ker-Is: ATU 675 in Brittany", Fabula 54, 3-4 (2013): 235-262, doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/fabula-2013-0020

- ^ Dardy, Leopold. Anthologie populaire de l'Albret (sud-ouest de l'Agenais ou Gascogne landaise). Tome II. J. Michel et Médan. 1891. pp. 62-71.

- ^ Pedroso, Consiglieri. Portuguese Folk-Tales. London: Published for the Folk-Lore Society. 1882. pp. 72-74.

- ^ Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1-2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. pp. 45-53.

- ^ Puchner, Walter. "Argyrō Xenophōntos, Kōnstantina Kōnstantinou (eds.): Ta paramythia tēs Kyprou apo to Laographiko Archeio tou Kentrou Epistemonikōn Ereunōn 2015 [compte-rendu]". In: Fabula 57, no. 1-2 (2016): 188-190. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabula-2016-0032

- ^ Pitré, Giuseppe. Catarina the Wise and Other Wondrous Sicilian Folk and Fairy Tales. Edited and Translated by Jack Zipes. Illustrated by Adeetje Bouma. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. 217. pp. 203-206 and 275-276. ISBN 978-0-226-46279-0

- ^ Laboulaye, Édouard. "Zerbino the Bumpkin." In: Smack-Bam, or The Art of Governing Men: Political Fairy Tales of Édouard Laboulaye. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2018. pp. 81-116. Accessed April 1, 2021. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc7781n.6.

- ^ Laboulaye, Edouard; Booth, Mary Louise. Last fairy tales. New York: Harper & Brothers. [ca. 1884] pp. 108-150. [2]

- ^ Millar, H. R. The Golden Fairy Book. London: Hutchinson & Co.. 1894. pp. 293-320.

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. pp. 68-71. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. p. 146-147.

- ^ Kuhn Adalbert. Märkische Sagen und Märchen nebst einem Anhange von Gebräuchen und Aberglauben. Berlin: 1843. pp. 270-273.

- ^ Grundtvig, Sven. Danske Folkeaeventyr: Efter Utrykte Kilder. Kjøbenhaven: C. A. Reitzel. 1876. pp. 117-124. [3]

- ^ Kamp, Jens Nielsen. Danske Folkeaeventyr. Kjøbenhavn: Wøldike, 1879. pp. 160-169. [4]

- ^ Grundtvig, Svend. Gamle Danske Minder I Folkemunde. Ny Samling. Kjøbenhaven: C. G. Iversen, 1857. pp. 308-309. [5]

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Apo, Satu. 2012. "Satugenre Kirjallisuudentutkimuksen Ja Folkloristiikan Riitamaana”. In: Elore 19 (2)/2012: 24. ISSN 1456-3010.

- ^ Loorits, Oskar. Estnische Volkserzählungen. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. 1959. p. 3.

- ^ Leskien, August. Balkanmärchen. Jena: Eugen Diederichs, 1915. pp. 12-15.

- ^ Shapkarev, Kuzman. Сборник от български народни умотворения [The Bulgarian Folklore Collection]. Vol. VIII: Български прикаски и вѣрования съ прибавление на нѣколко Македоновлашки и Албански [Bulgarian folktales and beliefs with some Macedo-Romanian and Albanian]. 1892. pp. 172-173.

- ^ Bálint Péter. Átok, titok és ígéret a népméseben [The Curse, the Secret and the Promise in the Folktale]. Fabula Aeterna V. Edited by Péter Bálint. Debrecen: Didakt Kft. 2018. p. 337 (footnote nr. 76). ISBN 978-615-5212-65-9

- ^ Dobos Ilona. Gyémántkígyó: Ordódy József és Kovács Károly meséi. Budapest: Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, 1980. pp. 309-321.

- ^ Zarych, Elżbieta. “Ludowe, Literackie I Romantyczne W Górnośląskich Baśniach I Podaniach (Oberschlesiche Märchen Und Sagen) Josepha von Eichendorffa”. In: Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857) a Česko-Polská kulturnÍ a Umělecká pohraničÍ: kolektivnÍ Monografie [Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857) I Czesko-Polskie Kulturowe I Artystyczne Pogranicza: Monografia Zbiorowa]. Edited by Libor Martinek and Małgorzata Gamrat. KLP - Koniasch Latin Press, 2018. pp. 75–80, 84-86. http://bohemistika.fpf.slu.cz/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/eichendorff-komplet.pdf

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ McCarthy, William Bernard. Cinderella in America: a book of folk and fairy tales. The University Press of Mississippi. 2007. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-57806-959-0.

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Carrière, Joseph Médard. Tales From the French Folk-lore of Missouri. Evanston: Northwestern university, 1937. pp. 212-215.

- ^ Palleiro, María. "Charms and Wands in John the Lazy: Performance and Beliefs in Argentinean Folk Narrative". In: Acta Ethnographica Hungarica AETHN 64, 2 (2019): 353-368. Accessed Jul 21, 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1556/022.2019.64.2.7

- ^ Landes, Antoine. Contes et légendes annamites. Imprimerie coloniale, 1886. p. 150.

- ^ Landes, Antony. Contes tjames. Imprimerie coloniale, 1887. pp. 37-43.

- ^ Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. p. 489.

- ^ Crane, Thomas Frederick. 'Italian Popular Tales. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. 1885. p. 320.

Bibliography[]

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 485-489.

Further reading[]

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B. (1993). "Luckless, Witless, and Filthy-Footed: A Sociocultural Study and Publishing History Analysis of "The Lazy Boy"". The Journal of American Folklore. 106 (421): 259–284. doi:10.2307/541421. JSTOR 541421.

External links[]

- Italian fairy tales

- Fiction about magic

- Laughter

- Fiction about shapeshifting

- Works about marriage