Pessimism

Pessimism is a negative mental attitude in which an undesirable outcome is anticipated from a given situation. Pessimists tend to focus on the negatives of life in general. A common question asked to test for pessimism is "Is the glass half empty or half full?"; in this situation, a pessimist is said to see the glass as half empty, while an optimist is said to see the glass as half full. Throughout history, the pessimistic disposition has had effects on all major areas of thinking.[1]

Philosophical pessimism is the related idea that views the world in a strictly anti-optimistic fashion. This form of pessimism is not an emotional disposition as the term commonly connotes. Instead, it is a philosophy or worldview that directly challenges the notion of progress and what may be considered the faith-based claims of optimism. Philosophical pessimists are often existential nihilists believing that life has no intrinsic meaning or value. Their responses to this condition, however, are widely varied and often life-affirming.

Etymology[]

The term pessimism derives from the Latin word pessimus meaning 'the worst'. It was first used by Jesuit critics of Voltaire's 1759 novel Candide, ou l'Optimisme. Voltaire was satirizing the philosophy of Leibniz who maintained that this was the 'best (optimum) of all possible worlds'. In their attacks on Voltaire, the Jesuits of the Revue de Trévoux accused him of pessimisme.[2]:9

Philosophical pessimism[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Philosophical pessimism |

Philosophical pessimism is not a state of mind or a psychological disposition, but rather it is a worldview or ethic that seeks to face up to perceived distasteful realities of the world and eliminate irrational hopes and expectations (such as the idea of progress and religious faith) which may lead to undesirable outcomes. Ideas which prefigure philosophical pessimism can be seen in ancient texts such as the Dialogue of Pessimism and Ecclesiastes; maintaining that everything is hevel (literally 'vapor' or 'breath').

In Western philosophy, philosophical pessimism is not a single coherent movement, but rather a loosely associated group of thinkers with similar ideas and a family resemblance to each other.[2]:7 In Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit, Joshua Foa Dienstag outlines the main propositions shared by most philosophical pessimists as "that time is a burden; that the course of history is in some sense ironic; that freedom and happiness are incompatible; and that human existence is absurd."[2]:19

Philosophical pessimists see the self-consciousness of man as bound up with his consciousness of time and that this leads to greater suffering than mere physical pain. While many organisms live in the present, humans and certain species of animals can contemplate the past and future, and this is an important difference. Human beings have foreknowledge of their own eventual fate and this "terror" is present in every moment of our lives as a reminder of the impermanent nature of life and of our inability to control this change.[2]:22

The philosophical pessimistic view of the effect of historical progress tends to be more negative than positive. The philosophical pessimist does not deny that certain areas like science can "progress" but they deny that this has resulted in an overall improvement of the human condition. In this sense it could be said that the pessimist views history as ironic; while seemingly getting better, it is mostly in fact not improving at all, or getting worse.[2]:25 This is most clearly seen in Rousseau's critique of enlightenment civil society and his preference for man in the primitive and natural state. For Rousseau, "our souls have become corrupted to the extent that our sciences and our arts have advanced towards perfection".[3]

The pessimistic view of the human condition is that it is in a sense "absurd". Absurdity is seen as an ontological mismatch between our desire for meaning and fulfillment and our inability to find or sustain those things in the world, or as Camus puts it: "a divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting".[4] The idea that rational thought would lead to human flourishing can be traced to Socrates and is at the root of most forms of western optimistic philosophies. Pessimism turns the idea on its head; it faults the human freedom to reason as the feature that misaligned humanity from our world and sees it as the root of human unhappiness.[2]:33–34

The responses to this predicament of the human condition by pessimists are varied. Some philosophers, such as Schopenhauer and Mainländer, recommend a form of resignation and self-denial (which they saw exemplified in Indian religions and Christian monasticism). Some followers tend to believe that "expecting the worst leads to the best." Rene Descartes even believed that life was better if emotional reactions to "negative" events were removed. Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann asserted that with cultural and technological progress, the world and its inhabitants will reach a state in which they will voluntarily embrace nothingness. Others like Nietzsche, Leopardi, Julius Bahnsen and Camus respond with a more life-affirming view, what Nietzsche called a "Dionysian pessimism", an embrace of life as it is in all of its constant change and suffering, without appeal to progress or hedonistic calculus. Albert Camus indicated that the common responses to the absurdity of life are often: Suicide, a leap of faith (as per Kierkegaard's knight of faith), or recognition/rebellion. Camus rejected all but the last option as unacceptable and inauthentic responses.[4]

Philosophical pessimism has often been tied to the arts and literature. Schopenhauer's philosophy was very popular with composers (Wagner, Brahms and Mahler).[5] While there are earlier examples of literary pessimism, such as in the work of Miguel de Cervantes, several philosophical pessimists also wrote novels or poetry (Camus and Leopardi respectively). A distinctive literary form which has been associated with pessimism is aphoristic writing, and this can be seen in Leopardi, Nietzsche and Cioran. Nineteenth and twentieth-century writers who could be said to express pessimistic views in their works or to be influenced by pessimistic philosophers include Charles Baudelaire,[6] Samuel Beckett,[7] Gottfried Benn,[8] Jorge Luis Borges,[9] Charles Bukowski, Dino Buzzati,[10] Lord Byron,[11] Louis-Ferdinand Céline,[12] Joseph Conrad,[13] Fyodor Dostoevsky,[2]:6 Mihai Eminescu,[14] Sigmund Freud,[15] Thomas Hardy,[16] Sadegh Hedayat,[17] H. P. Lovecraft,[18] Thomas Mann,[2]:6 Camilo Pessanha, Edgar Saltus[19] and James Thomson.[20] Late-twentieth and twenty-first century authors who could be said to express or explore philosophical pessimism include David Benatar,[21] Thomas Bernhard,[22] Friedrich Dürrenmatt,[23] John Gray,[24] Michel Houellebecq,[25] Alexander Kluge, Thomas Ligotti,[18] Cormac McCarthy,[26] Eugene Thacker,[27] and Peter Wessel Zapffe.[28]

Notable proponents[]

Ancient Greeks[]

In Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, Friedrich Nietzsche argued that the pre-Socratic philosophers such as Anaximander, Heraclitus (called "the Weeping Philosopher") and Parmenides represented a classical form of pessimism. Nietzsche saw Anaximander's philosophy as the "enigmatic proclamation of a true pessimist". Similarly, of Heraclitus' philosophy of flux and strife he wrote:

Heraclitus denied the duality of totally diverse worlds—a position which Anaximander had been compelled to assume. He no longer distinguished a physical world from a metaphysical one, a realm of definite qualities from an undefinable "indefinite." And after this first step, nothing could hold him back from a second, far bolder negation: he altogether denied being. For this one world which he retained [...] nowhere shows a tarrying, an indestructibility, a bulwark in the stream. Louder than Anaximander, Heraclitus proclaimed: "I see nothing other than becoming. Be not deceived. It is the fault of your short-sightedness, not of the essence of things, if you believe you see land somewhere in the ocean of becoming and passing-away. You use names for things as though they rigidly, persistently endured; yet even the stream into which you step a second time is not the one you stepped into before." The Birth of Tragedy. 5, pp. 51–52

Another Greek expressed a form of pessimism in his philosophy: the ancient Cyrenaic philosopher Hegesias (290 BCE). Like later pessimists, Hegesias argued that lasting happiness is impossible to achieve and that all we can do is to try to avoid pain as much as possible.

Complete happiness cannot possibly exist; for that the body is full of many sensations, and that the mind sympathizes with the body, and is troubled when that is troubled, and also that fortune prevents many things which we cherished in anticipation; so that for all these reasons, perfect happiness eludes our grasp.[29]

Hegesias held that all external objects, events, and actions are indifferent to the wise man, even death: "for the foolish person it is expedient to live, but to the wise person it is a matter of indifference".[29] According to Cicero, Hegesias wrote a book called Death by Starvation, which supposedly persuaded many people that death was more desirable than life. Because of this, Ptolemy II Philadelphus banned Hegesias from teaching in Alexandria.[30]

From the 3rd century BCE, Stoicism propounded as an exercise "the premeditation of evils"—concentration on worst possible outcomes.[31]

Baltasar Gracián[]

Schopenhauer engaged extensively with the works of Baltasar Gracián (1601–1658) and considered Gracián's novel El Criticón "Absolutely unique... a book made for constant use...a companion for life" for "those who wish to prosper in the great world".[32] Schopenhauer's pessimistic outlook was influenced by Gracián, and he translated Gracián's The Pocket Oracle and Art of Prudence into German. He praised Gracián for his aphoristic writing style (conceptismo) and often quoted him in his works.[33] Gracian's novel El Criticón (The Critic) is an extended allegory of the human search for happiness which turns out to be fruitless on this Earth. The Critic paints a bleak and desolate picture of the human condition. His Pocket Oracle was a book of aphorisms on how to live in what he saw as a world filled with deception, duplicity, and disillusionment.[34]

Voltaire[]

Voltaire was the first European to be labeled as a pessimist[citation needed] due to his critique of Alexander Pope's optimistic "An Essay on Man", and Leibniz' affirmation that "we live in the best of all possible worlds." Voltaire's novel Candide is an extended criticism of theistic optimism and his Poem on the Lisbon Disaster is especially pessimistic about the state of mankind and the nature of God. Though himself a Deist, Voltaire argued against the existence of a compassionate personal God through his interpretation of the problem of evil.[35]

Jean-Jacques Rousseau[]

Rousseau first presented the major themes of philosophical pessimism, and he has been called "the patriarch of pessimism".[2]:49 For Rousseau, humans in their "natural goodness" have no sense of self-consciousness in time and thus are happier than humans corrupted by society. Rousseau saw the movement out of the state of nature as the origin of inequality and mankind's lack of freedom. The wholesome qualities of man in his natural state, a non-destructive love of self and compassion are gradually replaced by amour propre, self-love driven by pride and jealousy of his fellow man. Because of this, modern man lives "always outside himself", concerned with other men, the future, and external objects. Rousseau also blames the human faculty of "perfectibility" and human language for tearing us away from our natural state by allowing us to imagine a future in which we are different than what we are now and therefore making us appear inadequate to ourselves (and thus 'perfectible').[2]:60

Rousseau saw the evolution of modern society as the replacement of natural egalitarianism by alienation and class distinction enforced by institutions of power. Thus The Social Contract opens with the famous phrase "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains." Even the ruling classes are not free, in fact for Rousseau they are "greater slaves" because they require more esteem from others to rule and must therefore constantly live "outside themselves".

Giacomo Leopardi[]

Though a lesser-known figure outside Italy, Giacomo Leopardi was highly influential in the 19th century, especially for Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.[2]:50 In Leopardi's darkly comic essays, aphorisms, fables and parables, life is often described as a sort of divine joke or mistake. According to Leopardi, because of our conscious sense of time and our endless search for truth, the human desire for happiness can never be truly satiated and joy cannot last. Leopardi claims that "Therefore they greatly deceive themselves, [those] who declare and preach that the perfection of man consists in knowledge of the truth and that all his woes proceed from false opinions and ignorance, and that the human race will at last be happy, when all or most people come to know the truth, and solely on the grounds of that arrange and govern their lives."[2]:67 Furthermore, Leopardi believes that for man it is not possible to forget truth and that "it is easier to rid oneself of any habit before that of philosophizing."

Leopardi's response to this condition is to face up to these realities and try to live a vibrant and great life, to be risky and take up uncertain tasks. This uncertainty makes life valuable and exciting but does not free us from suffering, it is rather an abandonment of the futile pursuit of happiness. He uses the example of Christopher Columbus who went on a dangerous and uncertain voyage and because of this grew to appreciate life more fully.[36] Leopardi also sees the capacity of humans to laugh at their condition as a laudable quality that can help us deal with our predicament. For Leopardi: "He who has the courage to laugh is master of the world, much like him who is prepared to die."[37]

Arthur Schopenhauer[]

Arthur Schopenhauer's pessimism comes from his elevating of Will above reason as the mainspring of human thought and behavior. The Will is the ultimate metaphysical animating noumenon and it is futile, illogical and directionless striving. Schopenhauer sees reason as weak and insignificant compared to Will; in one metaphor, Schopenhauer compares the human intellect to a lame man who can see, but who rides on the shoulder of the blind giant of Will.[38] Schopenhauer saw human desires as impossible to satisfy. He pointed to motivators such as hunger, thirst, and sexuality as the fundamental features of the Will in action, which are always by nature unsatisfactory.

All satisfaction, or what is commonly called happiness, is really and essentially always negative only, and never positive. It is not a gratification which comes to us originally and of itself, but it must always be the satisfaction of a wish. For desire, that is to say, want, is the precedent condition of every pleasure; but with the satisfaction, the desire and therefore the pleasure cease; and so the satisfaction or gratification can never be more than deliverance from pain, from a want. Such is not only every actual and evident suffering, but also every desire whose importunity disturbs our peace, and indeed even the deadening boredom that makes existence a burden to us.[39]

Schopenhauer notes that once satiated, the feeling of satisfaction rarely lasts and we spend most of our lives in a state of endless striving; in this sense, we are, deep down, nothing but Will. Even the moments of satisfaction, when repeated often enough, only lead to boredom and thus human existence is constantly swinging "like a pendulum to and fro between pain and boredom, and these two are in fact its ultimate constituents".[40] This ironic cycle eventually allows us to see the inherent vanity at the truth of existence (nichtigkeit) and to realize that "the purpose of our existence is not to be happy".[41]

Moreover, the business of biological life is a war of all against all filled with constant physical pain and distress, not merely unsatisfied desires. There is also the constant dread of death on the horizon to consider, which makes human life worse than animals. Reason only compounds our suffering by allowing us to realize that biology's agenda is not something we would have chosen had we been given a choice, but it is ultimately helpless to prevent us from serving it.[38]

Schopenhauer saw in artistic contemplation a temporary escape from the act of willing. He believed that through "losing yourself" in art one could sublimate the Will. However, he believed that only resignation from the pointless striving of the will to live through a form of asceticism (as those practiced by eastern monastics and by "saintly persons") could free oneself from the Will altogether.

Schopenhauer never used the term pessimism to describe his philosophy but he also didn't object when others called it that.[42] Other common terms used to describe his thought were voluntarism and irrationalism which he also never used.

Post-Schopenhauerian pessimism[]

During the end-times of Schopenhauer's life and subsequent years after his death, post-Schopenhauerian pessimism became a rather popular "trend" in 19th century Germany.[43] Nevertheless, it was viewed with disdain by the other popular philosophies at the time, such as Hegelianism, materialism, neo-Kantianism and the emerging positivism. In an age of upcoming revolutions and exciting discoveries in science, the resigned and anti-progressive nature of the typical pessimist was seen as a detriment to social development. To respond to this growing criticism, a group of philosophers greatly influenced by Schopenhauer (indeed, some even being his personal acquaintances) developed their own brand of pessimism, each in their own unique way. Thinkers such as Julius Bahnsen, Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann, Philipp Mainländer and others cultivated the ever-increasing threat of pessimism by converting Schopenhauer's transcendental idealism into what Frederick C. Beiser calls transcendental realism.[44][45] The transcendental idealist thesis is that we know only the appearances of things (not things-in-themselves); the transcendental realist thesis is that "the knowledge we have of how things appear to us in experience gives us knowledge of things-in-themselves."[46]

By espousing transcendental realism, Schopenhauer's own dark observations about the nature of the world would become completely knowable and objective, and in this way, they would attain certainty. The certainty of pessimism being, that non-existence is preferable to existence. That, along with the metaphysical reality of the will, were the premises which the "post-Schopenhauerian" thinkers inherited from Schopenhauer's teachings. After this common starting point, each philosopher developed his own negative view of being in their respective philosophies. Some pessimists would "assuage" the critics by accepting the validity of their criticisms and embracing historicism, as was the case with Schopenhauer's literary executor Julius Frauenstädt and with Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann (who gave transcendental realism a unique twist).[46] Julius Bahnsen would reshape the understanding of pessimism overall,[47] while Philipp Mainländer set out to reinterpret and elucidate the nature of the will, by presenting it as a self-mortifying will-to-death.[48]

Friedrich Nietzsche[]

Friedrich Nietzsche could be said to be a philosophical pessimist even though unlike Schopenhauer (whom he read avidly) his response to the 'tragic' pessimistic view is neither resigned nor self-denying, but a life-affirming form of pessimism. For Nietzsche this was a "pessimism of the future", a "Dionysian pessimism."[49] Nietzsche identified his Dionysian pessimism with what he saw as the pessimism of the Greek pre-socratics and also saw it at the core of ancient Greek tragedy.[2]:167 He saw tragedy as laying bare the terrible nature of human existence, bound by constant flux. In contrast to this Nietzsche saw Socratic philosophy as an optimistic refuge of those who could not bear the tragic any longer. Since Socrates posited that wisdom could lead to happiness, Nietzsche saw this as "morally speaking, a sort of cowardice...amorally, a ruse".[2]:172 Nietzsche was also critical of Schopenhauer's pessimism because in judging the world negatively, it turned to moral judgments about the world and therefore led to weakness and nihilism. Nietzsche's response was a total embracing of the nature of the world, a "great liberation" through a "pessimism of strength" which "does not sit in judgment of this condition".[2]:178 Nietzsche believed that the task of the philosopher was to wield this pessimism like a hammer, to first attack the basis of old moralities and beliefs and then to "make oneself a new pair of wings", i.e. to re-evaluate all values and create new ones.[2]:181 A key feature of this Dionysian pessimism was 'saying yes' to the changing nature of the world, this entailed embracing destruction and suffering joyfully, forever (hence the ideas of amor fati and eternal recurrence).[2]:191 Pessimism for Nietzsche is an art of living that is "good for one's health" as a "remedy and an aid in the service of growing and struggling life".[2]:199

Albert Camus[]

In a 1945 article, Albert Camus wrote "the idea that a pessimistic philosophy is necessarily one of discouragement is a puerile idea."[50] Camus helped popularize the idea of "the absurd", a key term in his famous essay The Myth of Sisyphus. Like previous philosophical pessimists, Camus sees human consciousness and reason as that which "sets me in opposition to all creation".[51] For Camus, this clash between a reasoning mind which craves meaning and a 'silent' world is what produces the most important philosophical problem, the 'problem of suicide'. Camus believed that people often escape facing the absurd through "eluding" (l'esquive), a 'trickery' for "those who live not for life itself but some great idea that will transcend it, refine it, give it a meaning, and betray it".[51] He considered suicide and religion as inauthentic forms of eluding or escaping the problem of existence. For Camus, the only choice was to rebelliously accept and live with the absurd, for "there is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn." Camus' response to the absurd problem is illustrated by using the Greek mythic character of Sisyphus, who was condemned by the gods to push a boulder up a hill for eternity. Camus imagines Sisyphus while pushing the rock, realizing the futility of his task, but doing it anyway out of rebellion: "One must imagine Sisyphus happy."

Other forms[]

Epistemological[]

There are several theories of epistemology which could arguably be said to be pessimistic in the sense that they consider it difficult or even impossible to obtain knowledge about the world. These ideas are generally related to nihilism, philosophical skepticism and relativism.

Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743–1819), analyzed rationalism, and in particular Immanuel Kant's "critical" philosophy to carry out a reductio ad absurdum[citation needed] according to which all rationalism reduces to nihilism, and thus it should be avoided and replaced with a return to some type of faith and revelation.

Richard Rorty, Michel Foucault, and Ludwig Wittgenstein questioned whether our particular concepts could relate to the world in any absolute way and whether we can justify our ways of describing the world as compared with other ways. In general, these philosophers argue that truth was not about getting it right or representing reality, but was part of subjective social relations of power, or language-games that served our purposes in a particular time. Therefore, these forms of anti-foundationalism, while not being pessimistic per se, rejects any definitions that claim to have discovered absolute 'truths' or foundational facts about the world as valid.

Political and cultural[]

Philosophical pessimism stands opposed to the optimism or even utopianism of Hegelian philosophies. Emil Cioran claimed "Hegel is chiefly responsible for modern optimism. How could he have failed to see that consciousness changes only its forms and modalities, but never progresses?"[52] Philosophical pessimism is differentiated from other political philosophies by having no ideal governmental structure or political project, rather pessimism generally tends to be an anti-systematic philosophy of individual action.[2]:7 This is because philosophical pessimists tend to be skeptical that any politics of social progress can actually improve the human condition. As Cioran states, "every step forward is followed by a step back: this is the unfruitful oscillation of history".[53] Cioran also attacks political optimism because it creates an "idolatry of tomorrow" which can be used to authorize anything in its name. This does not mean however, that the pessimist cannot be politically involved, as Camus argued in The Rebel.

There is another strain of thought generally associated with a pessimistic worldview, this is the pessimism of cultural criticism and social decline which is seen in Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West. Spengler promoted a cyclic model of history similar to the theories of Giambattista Vico. Spengler believed modern western civilization was in the 'winter' age of decline (untergang). Spenglerian theory was immensely influential in interwar Europe, especially in Weimar Germany. Similarly, traditionalist Julius Evola thought that the world was in the Kali Yuga, a dark age of moral decline.

Intellectuals like Oliver James correlate economic progress with economic inequality, the stimulation of artificial needs, and affluenza. Anti-consumerists identify rising trends of conspicuous consumption and self-interested, image-conscious behavior in culture. Post-modernists like Jean Baudrillard have even argued that culture (and therefore our lives) now has no basis in reality whatsoever.[1]

Conservative thinkers, especially social conservatives, often perceive politics in a generally pessimistic way. William F. Buckley famously remarked that he was "standing athwart history yelling 'stop!'" and Whittaker Chambers was convinced that capitalism was bound to fall to communism, though he was himself staunchly anti-communist. Social conservatives often see the West as a decadent and nihilistic civilization which has abandoned its roots in Christianity and/or Greek philosophy, leaving it doomed to fall into moral and political decay. Robert Bork's Slouching Toward Gomorrah and Allan Bloom's The Closing of the American Mind are famous expressions of this point of view.

Many economic conservatives and libertarians believe that the expansion of the state and the role of government in society is inevitable, and they are at best fighting a holding action against it.[citation needed] They hold that the natural tendency of people is to be ruled and that freedom is an exceptional state of affairs which is now being abandoned in favor of social and economic security provided by the welfare state.[citation needed] Political pessimism has sometimes found expression in dystopian novels such as George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.[54] Political pessimism about one's country often correlates with a desire to emigrate.[55]

During the financial crisis of 2007–08 in the United States, the neologism "pessimism porn" was coined to describe the alleged eschatological and survivalist thrill some people derive from predicting, reading and fantasizing about the collapse of civil society through the destruction of the world's economic system.[56][57][58][59]

Technological and environmental[]

Technological pessimism is the belief that advances in science and technology do not lead to an improvement in the human condition. Technological pessimism can be said to have originated during the industrial revolution with the Luddite movement. Luddites blamed the rise of industrial mills and advanced factory machinery for the loss of their jobs and set out to destroy them. The Romantic movement was also pessimistic towards the rise of technology and longed for simpler and more natural times. Poets like William Wordsworth and William Blake believed that industrialization was polluting the purity of nature.[60]

Some social critics and environmentalists believe that globalization, overpopulation and the economic practices of modern capitalist states over-stress the planet's ecological equilibrium. They warn that unless something is done to slow this, climate change will worsen eventually leading to some form of social and ecological collapse.[61] James Lovelock believes that the ecology of the Earth has already been irretrievably damaged, and even an unrealistic shift in politics would not be enough to save it. According to Lovelock, the Earth's climate regulation system is being overwhelmed by pollution and the Earth will soon jump from its current state into a dramatically hotter climate.[62] Lovelock blames this state of affairs on what he calls "polyanthroponemia", which is when: "humans overpopulate until they do more harm than good." Lovelock states:

The presence of 7 billion people aiming for first-world comforts…is clearly incompatible with the homeostasis of climate but also with chemistry, biological diversity and the economy of the system.[62]

Some radical environmentalists, anti-globalization activists, and Neo-luddites can be said to hold to this type of pessimism about the effects of modern "progress". A more radical form of environmental pessimism is anarcho-primitivism which faults the agricultural revolution with giving rise to social stratification, coercion, and alienation. Some anarcho-primitivists promote deindustrialization, abandonment of modern technology and rewilding.

An infamous anarcho-primitivist is Theodore Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber who engaged in a nationwide mail bombing campaign. In his 1995 Unabomber manifesto, he called attention to the erosion of human freedom by the rise of the modern "industrial-technological system".[63] The manifesto begins thus:

The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in "advanced" countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation. It will certainly subject human beings to greater indignities and inflict greater damage on the natural world, it will probably lead to greater social disruption and psychological suffering, and it may lead to increased physical suffering even in "advanced" countries.

One of the most radical pessimist organizations is the voluntary human extinction movement which argues for the extinction of the human race through antinatalism.

Pope Francis' controversial 2015 encyclical on ecological issues is ripe with pessimistic assessments of the role of technology in the modern world.

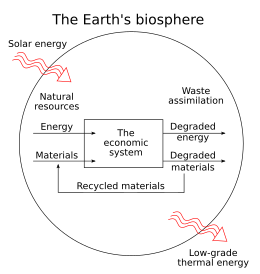

Entropy pessimism[]

"Entropy pessimism" represents a special case of technological and environmental pessimism, based on thermodynamic principles.[64]:116 According to the first law of thermodynamics, matter and energy is neither created nor destroyed in the economy. According to the second law of thermodynamics — also known as the entropy law — what happens in the economy is that all matter and energy is transformed from states available for human purposes (valuable natural resources) to states unavailable for human purposes (valueless waste and pollution). In effect, all of man's technologies and activities are only speeding up the general march against a future planetary "heat death" of degraded energy, exhausted natural resources and a deteriorated environment — a state of maximum entropy locally on earth; "locally" on earth, that is, when compared to the heat death of the universe, taken as a whole.

The term "entropy pessimism" was coined to describe the work of Romanian American economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, a progenitor in economics and the paradigm founder of ecological economics.[64]:116 Georgescu-Roegen made extensive use of the entropy concept in his magnum opus on The Entropy Law and the Economic Process.[65] Since the 1990s, leading ecological economist and steady-state theorist Herman Daly — a student of Georgescu-Roegen — has been the economists profession's most influential proponent of entropy pessimism.[66][67]:545

Among other matters, the entropy pessimism position is concerned with the existential impossibility of allocating Earth's finite stock of mineral resources evenly among an unknown number of present and future generations. This number of generations is likely to remain unknown to us, as there is no way — or only little way — of knowing in advance if or when mankind will ultimately face extinction. In effect, any conceivable intertemporal allocation of the stock will inevitably end up with universal economic decline at some future point.[68]:369–371 [69]:253–256 [70]:165 [71]:168–171 [72]:150–153 [73]:106–109 [67]:546–549 [74]:142–145

Entropy pessimism is a widespread view in ecological economics and in the degrowth movement.

Legal[]

Bibas writes that some criminal defense attorneys prefer to err on the side of pessimism: "Optimistic forecasts risk being proven disastrously wrong at trial, an embarrassing result that makes clients angry. On the other hand, if clients plead based on their lawyers' overly pessimistic advice, the cases do not go to trial and the clients are none the wiser."[75]

As a psychological disposition[]

In the ancient world, psychological pessimism was associated with melancholy, and was believed to be caused by an excess of black bile in the body. The study of pessimism has parallels with the study of depression. Psychologists trace pessimistic attitudes to emotional pain or even biology. Aaron Beck argues that depression is due to unrealistic negative views about the world. Beck starts treatment by engaging in conversation with clients about their unhelpful thoughts. Pessimists, however, are often able to provide arguments that suggest that their understanding of reality is justified; as in Depressive realism or (pessimistic realism).[1] Deflection is a common method used by those who are depressed. They let people assume they are revealing everything which proves to be an effective way of hiding.[76] The pessimism item on the Beck Depression Inventory has been judged useful in predicting suicides.[77] The Beck Hopelessness Scale has also been described as a measurement of pessimism.[78]

Wender and Klein point out that pessimism can be useful in some circumstances: "If one is subject to a series of defeats, it pays to adopt a conservative game plan of sitting back and waiting and letting others take the risks. Such waiting would be fostered by a pessimistic outlook. Similarly if one is raking in the chips of life, it pays to adopt an expansive risk-taking approach, and thus maximize access to scarce resources."[79]

Criticism[]

Pragmatic criticism[]

Through history, some have concluded that a pessimistic attitude, although justified, must be avoided to endure. Optimistic attitudes are favored and of emotional consideration.[80] Al-Ghazali and William James rejected their pessimism after suffering psychological, or even psychosomatic illness. Criticisms of this sort however assume that pessimism leads inevitably to a mood of darkness and utter depression. Many philosophers would disagree, claiming that the term "pessimism" is being abused. The link between pessimism and nihilism is present, but the former does not necessarily lead to the latter, as philosophers such as Albert Camus believed. Happiness is not inextricably linked to optimism, nor is pessimism inextricably linked to unhappiness. One could easily imagine an unhappy optimist, and a happy pessimist. Accusations of pessimism may be used to silence legitimate criticism. The economist Nouriel Roubini was largely dismissed as a pessimist, for his dire but accurate predictions of a coming global financial crisis, in 2006. Personality Plus opines that pessimistic temperaments (e.g. melancholy and phlegmatic) can be useful inasmuch as pessimists' focus on the negative helps them spot problems that people with more optimistic temperaments (e.g. choleric and sanguine) miss.

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bennett, Oliver (2001). Cultural Pessimism: Narratives of Decline in the Postmodern World. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0936-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Dienstag, Joshua Foa (2009). Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-6911-4112-1.

- ^ Rousseau, Jean Jacques (1750). Discourse on the Arts and Sciences.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus

- ^ "Arthur Schopenhauer", Wicks, Robert "Arthur Schopenhauer", Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2017, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Marinoni, A. (1913). "The Poetry of Charles Baudelaire". The Sewanee Review. 21 (1): 19–33. ISSN 0037-3052. JSTOR 27532587.

- ^ McDonald, Ronan (2002). "Beyond Tragedy: Samuel Beckett and the Art of Confusion". In McDonald, Ronan (ed.). Tragedy and Irish Literature. Tragedy and Irish Literature: Synge, O’Casey, Beckett. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 127–171. doi:10.1057/9781403913654_4. ISBN 978-1-4039-1365-4.

- ^ Eykman, Christoph (1985), Tymieniecka, Anna-Teresa (ed.), "Thalassic Regression: The Cipher of the Ocean in Gottfried Benn's Poetry", Poetics of the Elements in the Human Condition: The Sea: From Elemental Stirrings to Symbolic Inspiration, Language, and Life-Significance in Literary Interpretation and Theory, Analecta Husserliana, Springer Netherlands, pp. 353–366, doi:10.1007/978-94-015-3960-9_25, ISBN 978-94-015-3960-9

- ^ Santis, Esteban (2012-05-01). "Towards the finite a case against infinity in Jorge Luis Borges". Him 1990-2015.

- ^ Zanca, Valentina (January 2010). "Dino Buzzati's "Poem Strip"". Words Without Borders. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Wieman, Henry N. (1931). Tsanoff, Radoslav A. (ed.). "The Paradox of Pessimism". The Journal of Religion. 11 (3): 467–469. doi:10.1086/481092. ISSN 0022-4189. JSTOR 1196632. S2CID 170257475.

- ^ "The Selected Correspondence of Louis-Ferdinand Céline". The Brooklyn Rail. 2014-06-05. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ "Joseph Conrad: A Writer's Writer". Christian Science Monitor. 1991-04-22. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Tappe, E. D. (1951). "The Centenary of Mihai Eminescu". American Slavic and East European Review. 10 (1): 50–55. doi:10.2307/2491746. ISSN 1049-7544. JSTOR 2491746.

- ^ Southard, E. E. (1919). "Sigmund Freud, pessimist". The Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 14 (3): 197–216. doi:10.1037/h0072095. ISSN 0021-843X.

- ^ Diniejko, Andrzej (2014-09-06). "Thomas Hardy's Philosophical Outlook". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ A, Razi; Masoud, Bahrami (2006-01-01). "Origins and Causes of Sadegh Hedayat's Despair". Literary Research. 3 (11): 93–112.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stoneman, Ethan (2017-04-01). "No, everything is not all right: Supernatural horror as pessimistic argument". Horror Studies. 8 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1386/host.8.1.25_1.

- ^ Saltus, Edgar (1887). The Philosophy of Disenchantment. Boston, New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Co.

- ^ Seed, David (1999). "Hell is a city: symbolic systems and epistemological scepticism in The City of Dreadful Night". In Byron, Glennis; Punter, David (eds.). Spectral Readings. Spectral Readings: Towards a Gothic Geography. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 88–107. doi:10.1057/9780230374614_6. ISBN 978-0-230-37461-4.

- ^ Rothman, Joshua (2017-11-27). "The Case for Not Being Born". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Franklin, Ruth (2006-12-18). "The Art of Extinction". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Plouffe, Bruce (2007-02-20). "Friedrich Dürrenmatt's Der Auftrag : An Exception within an Oeuvre of Cultural Pessimism and Worst Possible Outcomes". Seminar: A Journal of Germanic Studies. 43 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1353/smr.2007.0018. ISSN 1911-026X. S2CID 170925530.

- ^ Skidelsky, Edward (2002-10-02). "The philosopher of pessimism. John Gray is one of the most daring and original thinkers in Britain. But his new book, a bold, anti-humanist polemic, fails to convince Edward Skidelsky". New Statesman. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Thomson, Ian (2019-10-30). "Why is Houellebecq's remorseless pessimism so appealing?". Catholic Herald. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Cowley, Jason (2008-01-12). "Jason Cowley on the novels of Cormac McCarthy". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Thacker, Eugene (2018). Infinite Resignation: On Pessimism. Watkins Media. ISBN 978-1-912248-20-9.

- ^ Tangenes, Gisle R. (March–April 2004). "The View from Mount Zapffe". Philosophy Now. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones i. 34

- ^

Burkeman, Oliver (2012). The Antidote: Happiness for people who can't stand positive thinking. Text Publishing. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9781921922671. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

[...] the Stoics propose a[n] elegant, sustainable and calming way to deal with the possibility of things going wrong: rather than struggling to avoid all thought of these worst-case scenarios, they counsel actively dwelling on them, staring them in the face. This brings us to an important milestone on the negative path to happiness — a psychological tactic that William [B.] Irvine argues is 'the single most valuable technique in the Stoics' toolkit'. He calls it 'negative visualization'. The Stoics themselves, rather more pungently, called it 'the premeditation of evils'.

- ^ Duff, E. Grant (2016-03-26). "Balthasar Gracian". fortnightlyreview.co.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Cartwright, David E. (2005). History dictionary of Schopenhauer's philosophy. Scarecrow press, Inc.

- ^ Gracian, Balthasar (2011). The Pocket Oracle and Art of Prudence. Penguin books.

- ^ Alp Hazar Büyükçulhacı (13 January 2014). "Candide: Thoughts of Voltaire on Optimism, Philosophy and "The Other"". Retrieved 23 July 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Leopardi, Giacomo. Dialogue between Columbus and Pedro Gutierrez (Operette morali).

- ^ Leopardi, Giacomo (2018). Thoughts. Translated by Nichols, J.G. Richmond: Alma Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7145-4826-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schopenhauer, Arthur (2007). Studies in Pessimism. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60206-349-5.

- ^ Arthur Schopenhauer. The World as Will and Representation. Vol. 1, Book IV, §58. Translated by Payne, E. F. J. Dover. p. 319.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur, The world as will and representation, pg 312

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur, The world as will and representation, vol II, pg 635

- ^ Cartwright, David E. (2010). Schopenhauer: a Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 4

- ^ Monika Langer, Nietzsche's Gay Science: Dancing Coherence, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 231.

- ^ Beiser reviews the commonly held position that Schopenhauer was a transcendental idealist and he rejects it: "Though it is deeply heretical from the standpoint of transcendental idealism, Schopenhauer's objective standpoint involves a form of transcendental realism, i.e. the assumption of the independent reality of the world of experience." (Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 40).

- ^ Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 213 n. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 147–8.

- ^ Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 231.

- ^ Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 202.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich, Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, book V

- ^ Albert Camus, Pessimism and Courage, Combat, September 1945

- ^ Jump up to: a b Camus, Albert (1991). Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-73373-7.

- ^ Cioran, Emil. A short history of decay, pg 146

- ^ Cioran, Emil. A short history of decay, pg 178

- ^ Lowenthal, D (1969), "Orwell's Political Pessimism in '1984'", Polity, 2 (2): 160–175, doi:10.2307/3234097, JSTOR 3234097, S2CID 156005171

- ^ Brym, RJ (1992), "The emigration potential of Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Russia: recent survey results", International Sociology, 7 (4): 387–95, doi:10.1177/026858092007004001, PMID 12179890, S2CID 5989051

- ^ Pessimism Porn: A soft spot for hard times, Hugo Lindgren, New York, February 9, 2009; accessed July 8, 2012

- ^ Pessimism Porn? Economic Forecasts Get Lurid, Dan Harris, ABC News, April 9, 2009; accessed July 8, 2012

- ^ Apocalypse and Post-Politics: The Romance of the End, Mary Manjikian, Lexington Books, March 15, 2012, ISBN 0739166220

- ^ Pessimism Porn: Titillatingly bleak media reports, Ben Schott, New York Times, February 23, 2009; accessed July 8, 2012

- ^ "Romanticism". Wsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ The New York Review of Books The Global Delusion, John Gray

- ^ Jump up to: a b The New York Review of Books A Great Jump to Disaster?, Tim Flannery

- ^ The Washington Post: Unabomber Special Report: INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY AND ITS FUTURE

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ayres, Robert U. (2007). "On the practical limits to substitution" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 61: 115–128. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.011.

- ^ Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1971). The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (Full book accessible at Scribd). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674257801.

- ^ Daly, Herman E. (2015). "Economics for a Full World". Scientific American. 293 (3): 100–7. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0905-100. PMID 16121860. S2CID 13441670. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kerschner, Christian (2010). "Economic de-growth vs. steady-state economy" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 18 (6): 544–551. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.10.019.

- ^ Daly, Herman E., ed. (1980). Economics, Ecology, Ethics. Essays Towards a Steady-State Economy (PDF contains only the introductory chapter of the book) (2nd ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0716711780.

- ^ Rifkin, Jeremy (1980). Entropy: A New World View (PDF). New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670297177. Archived from the original (PDF contains only the title and contents pages of the book) on 2016-10-18.

- ^ Boulding, Kenneth E. (1981). Evolutionary Economics. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0803916487.

- ^ Martínez-Alier, Juan (1987). Ecological Economics: Energy, Environment and Society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631171461.

- ^ Gowdy, John M.; Mesner, Susan (1998). "The Evolution of Georgescu-Roegen's Bioeconomics" (PDF). Review of Social Economy. 56 (2): 136–156. doi:10.1080/00346769800000016.

- ^ Schmitz, John E.J. (2007). The Second Law of Life: Energy, Technology, and the Future of Earth As We Know It (Author's science blog, based on his textbook). Norwich: William Andrew Publishing. ISBN 978-0815515371.

- ^

Perez-Carmona, Alexander (2013). "Growth: A Discussion of the Margins of Economic and Ecological Thought". In Meuleman, Louis (ed.). Transgovernance. Advancing Sustainability Governance (Article accessible at SlideShare)

|format=requires|url=(help). Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 83–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-28009-2_3. ISBN 9783642280085. - ^ Bibas, Stephanos (Jun 2004), Plea Bargaining outside the Shadow of Trial, 117, Harvard Law Review, pp. 2463–2547

- ^ Kirszner, Laurie (January 2012). Patterns for College Writing. United States: Bedford/St.Martins. p. 477. ISBN 978-0-312-67684-1.

- ^ Beck, AT; Steer, RA; Kovacs, M (1985), "Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation", American Journal of Psychiatry, 142 (5): 559–563, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.6328, doi:10.1176/ajp.142.5.559, PMID 3985195

- ^ Beck, AT; Weissman, A; Lester, D; Trexler, L (1974), "The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale", Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Journal of Consulting and Clinical, 42 (6): 861–5, doi:10.1037/h0037562, PMID 4436473

- ^ Wender, PH; Klein, DF (1982), Mind, Mood and Medicine, New American Library

- ^ Michau, Michael R. ""Doing, Suffering, and Creating": William James and Depression" (PDF). web.ics.purdue.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

Further reading[]

- Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0-19-876871-5

- Dienstag, Joshua Foa, Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit, Princeton University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-691-12552-X

- Nietzsche, Friedrich, The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, New York: Vintage Books, 1967, ISBN 0-394-70369-3

- Slaboch, Matthew W., A Road to Nowhere: The Idea of Progress and Its Critics, The University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018, ISBN 0-812-24980-1

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pessimism |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Philosophical pessimism |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Contestabile, Bruno (2016). "The Denial of the World from an Impartial View". Contemporary Buddhism. 17: 49–61. doi:10.1080/14639947.2015.1104003. S2CID 148168698.

- Emotions

- Epistemology

- Ethical theories

- Motivation

- Philosophy of life