Phra Malai

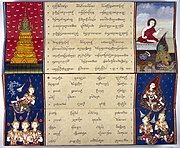

Phra Malai Kham Luang (Thai: พระมาลัยคำหลวง, pronounced [pʰráʔ māː.lāj kʰām lǔaŋ]) is the royal version of a Thai legendary poem of the Sri Lankan Arhat Maliyadeva whose stories are popular in Thai Theravada Buddhism. The vernacular version is known as Phra Malai Klon Suat.[1] Phra Malai is the subject of numerous palm-leaf manuscripts (in Thai bai lan), folding books (in Thai samut khoi), and artworks. His story, which includes concepts such as reincarnation, merit, and Buddhist cosmology, was a popular part of Thai funeral practices in the nineteenth century.

The legend of Phra Malai[]

Phra Malai, according to the various versions of the story, was a Buddhist monk who accumulated so much merit that he acquired great supernatural abilities. Using his powers, he traveled to the various Buddhist hells, where he meets the suffering denizens and is implored to have their living relatives make merit on their behalf. He later traveled to the heavenly realms of the devas, Trāyastriṃśa and Tushita, where he meets Indra and the future Buddha Maitreya, who instruct him further in merit-making.[2] Beyond the basic elements of the legend, further embellishments and flourishes were often added during recitations of the tale, to better entertain the audience.[3]

Phra Malai observing the suffering of adulterers in hell, Wat Machiram, Malaysia

Phra Malai instructing the dead in hell, Wat Machiram, Malaysia

Phra Malai in heaven, Cambodian example, Walters Art Museum

Phra Malai conversing with Indra, Wellcome Collection

Phra Malai manuscript on black paper, San Diego Museum of Art

18th century Phra Malai statue in the Bangkok style

History[]

The earliest known Phra Malai manuscript is dated C.S. 878[4] (CE 1516), written in Pali and vernacular Northern Thai language. However, most of the surviving manuscripts date from the late-18th and 19th centuries.[5] It is possible that the story originated in Sri Lanka, but it was only recorded in Southeast Asia, with its greatest popularity being in Thailand.[6] The Phra Malai story was often read at funerals as part of the entertainment during the wake, with many monks adding dramatic twists to entertain the audience. Starting during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), these performances were seen as inappropriate, and monks were banned from reciting Phra Malai during funerals, but the ban was circumvented by using former monks dressed in monastic robes to perform the recitations.[3]

Cultural depictions[]

Phra Malai was an extremely popular subject of illuminated manuscripts in 19th-century Thailand. The story was often written in folding samut khoi books, using Khom Thai script to write the Thai language, often in highly colloquial and risque style.[2] Most Phra Malai manuscripts include seven subjects, normally in pairs: devas or gods; monks attended by laymen; scenes of hell; scenes of picking lotus flowers; Phra Malai with Indra at a heavenly stupa; devas floating in the air; and contrasting scenes of quarreling evil people and meditating good people.[6] These books were used as chanting manuals for monks and novices; as it was considered very meritorious to produce or sponsor them, they were often produced as a lavishly decorated presentation volume for the recently deceased.[5]

See also[]

- Moggallāna, second of Lord Buddha's two foremost male disciples.

- Maliyadeva, one of the last well-known arhats who had high psychic powers according to Mahavamsa.

- Ksitigarbha, an East Asian figure with similar aspects.

- Karuṇā (Brahmavihara)

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phra Malai. |

- ^ Brereton, Bonnie Pacala (1995). Thai tellings of Phra Malai : texts and rituals concerning a popular Buddhist saint. Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9781881044079.

- ^ a b Heijdra, Martin, "The Legend of Phra Malai", Princeton University Graphic Arts Collection

- ^ a b Williams, Paul, and Ladwig, Patrice, Buddhist Funeral Cultures of Southeast Asia and China pp. 83-4

- ^ Brereton, Bonnie Pacala (1993). "Some Comments on a Northern Phra Malai Text Dated C.S. 878 (AD. 1516)". Academia.edu. Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 81.1. p. 141-5. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Igunma, Jana, "A Thai Book of Merit: Phra Malai's Journeys to Heaven and Hell, British Library Asian and African Studies Blog

- ^ a b Ginsburg, Henry, "Thai Art and Culture: Historic Manuscripts from Western Collections", pp. 92-111

- Thai Buddhist literature

- Buddhist mythology

- 1737 poems

- Thai poems