Plymouth red-bellied turtle

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (January 2011) |

| Plymouth red-bellied turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Plymouth red-bellied turtle on Long Pond in Plymouth, Massachusetts | |

Conservation status

| |

Endangered (ESA) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Pseudemys |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. r. bangsi

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi , 1937

| |

The Plymouth red-bellied turtle (Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi), sometimes called the Plymouth red-bellied cooter, was the first freshwater turtle in the US to be listed as endangered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.[1][2] Current thinking is that they are not a full subspecies and that they belong in synonymy under Pseudemys rubriventris or northern red-bellied cooter.[3] Nevertheless, it is well recognized that the Plymouth red-bellied turtle extends the range of the northern red-bellied cooter by 30–40 percent.[2]

Description[]

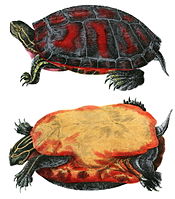

This turtle gets its name from its reddish plastron or undershell. They have flattened or slightly concave vertebral scutes with a red bar on each marginal scute. Their upper shell or carapace ranges from brown to black. An arrow-shaped stripe runs atop head, between the eyes, to their snout. Adults are 10–12.5 inches (25–32 cm).[4] Males have elongated, straight claws on the front feet.[5]

Distribution and habitat[]

This species lives in the Plymouth Pinelands of Massachusetts. It spends most of its time in bodies of deep, quickly moving freshwater with muddy bottoms and large amounts of vegetation. It can be found in lakes, ponds, creeks, rivers, streams, and marshes.[4]

Population features[]

It was found only in Plymouth County, Massachusetts before the state began trying to establish populations in other areas. The population was reduced to 200–300 turtles by the 1980s. By 2007, there were estimated to be 400–600 breeding age turtles across 20 ponds, and 2011 within 17 ponds.[6]

Ecology and behavior[]

The Plymouth red-bellied turtle often suns itself upon rocks in order to maintain its body temperature; however, if it is frightened while doing so, it will go back into the water. During the wintertime, this turtle hibernates in the mud at the bottoms of rivers.[4]

Predators[]

Eggs and young turtles are hunted by skunks, raccoons, birds, and fish.[7]

Life cycle[]

In spring and summer, the females nest in sand while the males look for food. Females lay 5–17 eggs at a time. The incubation of the eggs takes 73 to 80 days, and the eggs hatch at around 25 °C (77 °F). Hatchlings are about 32 millimetres (1.3 in) long. Their natural lifespan is 40 to 55 years.[4]

Conservation[]

The Plymouth red-bellied turtle is endangered due to overhunting by its natural predator, the skunk, and pollution from herbicides dumped into streams and ponds. Loss of habitat, as a result of filling in ponds to create houses is also a major issue.[2] In 1983, Massasoit National Wildlife Refuge was established to help conserve the Plymouth red-bellied turtle.

References[]

- ^ Endangered and Threatened Wildllfe and Plants; Listing as Endangered With Critical Habitat for the Plymouth Red-Bellied Turtle In Massachusetts Federal Register Vol. 45, No. 65 Wednesday, April 2, 1980

- ^ a b c "5 Year Review of pseudemys rubiventris northern red-bellied cooter" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. May 3, 2007. p. 30. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

Retain as endangered but amend listing to identify Plymouth County, Massachusetts population as a distinct population segment.

- ^ "Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ a b c d "Red-bellied Cooter | Chesapeake Bay Program". www.chesapeakebay.net. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- ^ "Species Profile: Plymouth Red-Bellied Cooter (Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi)". United States Fish and Wildlife Service (public domain). Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ Kiester, A. Ross; Olson, Deanna H. (2011). "Prime time for turtle conservation". Herpetological Review. 42 (2): 198–204.

- ^ "See a different endangered animal in every U.S. state". Animals. 2019-07-30. Retrieved 2019-09-29.

External links[]

- Graham, T.E. Summary report to Mass. Department of Fish and Wildlife, December 31, 1984.

- Pseudemys

- Turtles of North America

- Reptiles of the United States

- Endangered fauna of the United States

- ESA endangered species

- Subspecies