Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Hans Holbein the Younger painted the Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam several times, and his paintings were much copied, at the time and later. It is difficult to disentangle Holbein's original work from that of his workshop and other copyists. Possibly five largely original versions survive, as well as a number of drawings made as studies.

Holbein's portraits played an important part in spreading the painter's reputation across Europe, as they and their copies were widely distributed. When Holbein moved to England he had a letter of recommendation from Erasmus to Thomas More, in whose house he initially lived.

Commission[]

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466/69–1536) was a renowned humanist scholar and theologian. He moved in 1521 to Basel, the city where Hans Holbein the Younger lived and had his workshop. Such was the fame of Erasmus, who corresponded with scholars throughout Europe, that he needed many portraits of himself to send abroad to his protectors; although not an admirer of painting, he understood the power of image.[1] Quentin Matsys painted a noticeably younger Erasmus, writing, in 1517,[2] and used another profile portrait for a medal in 1519.[3] Albrecht Dürer made a portrait in engraving in 1526. But it was Holbein's images that were endlessly copied. Of the work Erasmus wrote in 1524, "Recently I sent again two portraits of Erasmus to France, painted by a very skillful artist. The artist carried along my portrait to France."[1]

Versions[]

There are three main portrait types: a three-quarters view, probably of 1523, best known from the National Gallery version; a profile view also from 1523, reading, as in the Louvre, and an older three-quarters view, perhaps c. 1530, probably best represented by the portrait miniature, a roundel 10cm across, in the Kunstmuseum Basel. One of the exhibited in the Kunstmuseum Basel was bought from Erasmus' widow by Bonifacius Amerbach in 1542.[4]

All of these were produced in many versions, several probably at least partly by Holbein himself, or supervised by him. The pose and face tends to remain the same, but the clothes and backgrounds vary. It seems to have been Holbein's practice to make a very careful drawing of his subjects (though no full drawings for any of these portraits survive) and to then produce the painted portrait without the sitter being present. The Louvre has drawings done as studies for the hands of both its painted version and the London version.

There is also a small emblematic depiction of an idealized Erasmus as the Roman god Terminus (his personal emblem), of 1532, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

London[]

The version also known as Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam with Renaissance Pilaster is a 1523 painting in oil and tempera on panel, in the National Gallery, London (on long-term loan from the Earl of Radnor). Holbein painted three much-copied portraits of Erasmus in 1523, of which this is the largest and most elaborate. It is likely the one sent to William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, in England. Holbein later painted Warham after he travelled to England in 1526 in search of work, with a recommendation from Erasmus, who had once lived in England himself. Holbein's portrait of Erasmus includes a Latin couplet by the scholar, inscribed on the edge of the leaning book on the shelf, which states that Holbein would rather have a slanderer than an imitator. According to art historian Stephanie Buck, this portrait is "an idealized picture of a sensitive, highly cultivated scholar, and this was precisely how Erasmus wanted to be remembered by future generations".[5]

The painting was formerly at Longford Castle, home of the Earl of Radnor, and may be referred to by this.

The Greek and Latin words on the book translate to "The Herculean Labours of Erasmus of Rotterdam".

Gallery[]

Oil and tempera on paper mounted on pine, Kunstmuseum Basel, version of the Louvre painting, thought to be all Holbein's own work

Royal Collection; the figure by Holbein and workshop, the church background added c. 1629

The late roundel, Kunstmuseum Basel. Perhaps 1532

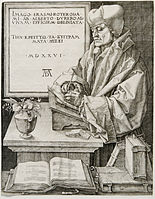

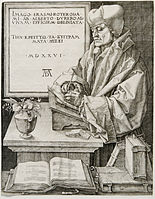

Albrecht Dürer engraving, 1526

Louvre, Study of right hand of Erasmus, with sketch of face. The hand relates to the London portrait; the face seems to be later, and related to the roundel of c. 1532

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erasmus by Hans Holbein der Jüngere. |

- ^ a b Bätschmann; Griener, 155

- ^ "Quinten Massys (1465/6-1530) - Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536)". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

- ^ Stein, Wilhelm (1929). Holbein der Jüngere. Berlin: Julius Bard Verlag. p. 78.

- ^ Landolt, Elisabeth (1984). Kabinettstücke der Amerbach im Historischen Museum Basel (in German). Basel: Stiftung für das Historische Museum Basel. p. 5. ISBN 3-85616-020-5.

- ^ Buck, Stephanie. Hans Holbein. Cologne: Könemann, 1999, ISBN 3829025831, p. 50

Sources[]

- Bätschmann, Oskar & Griener, Pascal. Hans Holbein. Reaktion Books, 1999. ISBN 1-86189-040-0

- 1523 paintings

- Portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger

- Collections of the National Gallery, London

- Paintings in the Louvre by Dutch, Flemish and German artists

- Portrait paintings in the Louvre

- Books in art