Primal Fear (film)

| Primal Fear | |

|---|---|

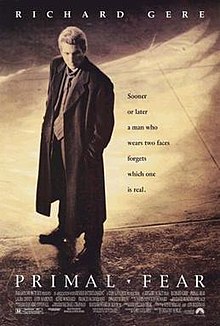

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Gregory Hoblit |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Primal Fear by William Diehl |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Chapman |

| Edited by | David Rosenbloom |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 130 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million |

| Box office | $102.6 million[1] |

Primal Fear is a 1996 American legal thriller film directed by Gregory Hoblit, based on William Diehl's 1993 novel of the same name. It stars Richard Gere as a Chicago defense attorney who believes that his altar boy client (played by Edward Norton in his film debut) is not guilty of murdering an influential Catholic archbishop.

Primal Fear was a box office success despite mixed reviews, though Norton's performance received universal acclaim. He was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture.[2]

Plot[]

Martin Vail is a Chicago defense attorney who loves the spotlight, and does everything that he can to get his high-profile clients acquitted on legal technicalities. One day he sees a news report about the arrest of Aaron Stampler, a 19-year-old altar boy from Kentucky with a severe stutter, who is accused of brutally murdering the beloved Archbishop Rushman. Vail jumps at the chance to represent the young man, pro bono. During his meetings at the County jail with Stampler, Vail comes to believe that his client is innocent, much to the chagrin of Vail's former lover, prosecutor Janet Venable.

As the trial begins, Vail discovers that powerful civic leaders, including the corrupt state's attorney John Shaughnessy, recently lost millions of dollars in real estate investments due to Rushman's decision not to develop on church-owned lands. Rushman secretly received numerous death threats as a result. Following a tip from a former altar boy about a videotape involving Stampler, Vail makes a search of the Archbishop's apartment and finds a VHS tape shot by Rushman that shows Stampler being sexually abused with another teenage altar boy and a teenage girl named Linda Forbes. Vail is now in a dilemma: introducing this evidence would make Stampler more sympathetic to the jury, but it would also give him a motive for the murder—which Venable has been unable to establish.

When Vail confronts his client and accuses him of having lied, Stampler breaks down crying and suddenly transforms into a new persona: a violent sociopath who calls himself "Roy." "Roy" confesses to the murder of the Archbishop, and threatens Vail. When this incident is over, Stampler once again becomes passive and shy, and appears to have no recollection of the personality switch - what he calls having "lost time." Molly Arrington, the neuropsychologist examining Stampler, is convinced that he has dissociative identity disorder, caused by years of physical and sexual abuse at the hands of his father and Rushman. Vail does not want to hear this, because he knows that he cannot enter an insanity plea during an ongoing trial.

Vail slowly sets up a confrontation in court by dropping hints about Rushman's pedophilia, as well as Stampler's multiple personalities. He also has the abuse tape delivered to Venable, knowing that she will realize who sent it—since she is under intense pressure from both Shaughnessy and her boss Bud Yancy to deliver a guilty verdict at any cost—and will use it as proof of motive.

At the climax, Vail puts Stampler on the witness stand and gently questions him about the sexual abuse he suffered at Rushman's hands. He also introduces evidence that Shaughnessy and Yancy had covered up evidence of Rushman molesting another young man. After Venable questions him harshly during cross-examination, Stampler turns into "Roy" in open court and attacks her, threatening to snap her neck if anyone comes near him. He is subdued by courthouse marshals and rushed back to his holding cell. The judge dismisses the jury in favor of a bench trial and then finds Stampler not guilty by reason of insanity, remanding him to a psychiatric hospital. Venable is fired for losing the case, and for allowing Rushman’s crimes to be publicly exposed.

Vail visits Stampler in his cell to tell him of the dismissal. Stampler claims to have no recollection of what happened in the courtroom, having again "lost time." However, as Vail is leaving, Stampler asks him to "tell Miss Venable I hope her neck is okay", which he could not have been able to remember if he had "lost time." When Vail confronts him, Stampler reveals that he had faked the personality disorder. No longer stuttering, he brags about having murdered Rushman, as well as Linda, his girlfriend. When Vail asks if there ever was a "Roy", Stampler replies that "there never was an 'Aaron.'" Stunned and disillusioned, Vail walks away and leaves the courthouse as Stampler taunts him from his cell.

Cast[]

- Richard Gere as Martin Vail

- Edward Norton as Aaron Stampler / Roy

- Laura Linney as Janet Venable

- John Mahoney as John Shaughnessy

- Alfre Woodard as Judge Shoat

- Frances McDormand as Dr. Molly Arrington

- Reg Rogers as Jack Connerman

- Terry O'Quinn as Bud Yancy

- Andre Braugher as Tommy Goodman

- Steven Bauer as Joey Pinero

- Joe Spano as Abel Stenner

- Tony Plana as Martinez

- Stanley Anderson as Archbishop Rushman

- Maura Tierney as Naomi Chance

- Jon Seda as Alex

- Kenneth Tigar as Weil

- Lester Holt as Lester Holt

Soundtrack[]

The soundtrack included Portuguese fado song "Canção do Mar" sung by Dulce Pontes.

Reception[]

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes reports an approval rating of 76% based on 46 reviews, with an average rating of 6.7/10. The site's critics consensus reads, "Primal Fear is a straightforward, yet entertaining thriller elevated by a crackerjack performance from Edward Norton."[3] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, gave it a weighted average score of 46 out of 100, based on 18 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[4] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[5]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times said the film has a "good deal of surface charm", but "the story relies on an overload of tangential subplots to keep it looking busy."[6] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote, "the plot is as good as crime procedurals get, but the movie is really better than its plot because of the three-dimensional characters." Ebert awarded Primal Fear three-and-a-half stars out of a possible four, described Gere's performance as one of the best in his career, praised Linney for rising above what might have been a stock character, and applauded Norton for offering a "completely convincing" portrayal.[7]

The film spent three weekends at the top of the U.S. box office.[1]

Accolades[]

Edward Norton's depiction of Aaron Stampler earned him multiple awards and nominations.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Aaron Stampler – Nominated Villain[28]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Courtroom Drama Film[29]

See also[]

- Mental illness in films

- Trial movies

- Plot twist

References[]

- ^ a b Primal Fear (1996). Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ^ Golden Globe Awards for 'Primal Fear' Retrieved 2017-05-09.

- ^ "Primal Fear (1996)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "Primal Fear Reviews". Metacritic.

- ^ "PRIMAL FEAR (1996) B+". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 2018-12-20.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (April 3, 1996). "A Murdered Archbishop, Lawyers In Armani". The New York Times. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (April 5, 1996). "Primal Fear 1996". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 14, 2018 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ "Primal Fear – Awards". IMDb. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "The 69th Academy Awards (1997) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "Primal Fear – Awards". IMDb. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Primal Fear – Awards". IMDb. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "BSFC Winners 1990s". bostonfilmcritics.org. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1997". BAFTA. 1997. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "1996 - 9th Annual Chicago Film Critics Awards". Chicago Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 1996". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008.

- ^ "1996 FFCC Award Winners". June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Primal Fear – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1990-99". kcfcc.org. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (16 December 1996). "Los Angeles Critics Honor 'Secrets and Lies'". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Richmond, Ray (April 18, 1997). "Bard Tops MTV List". Variety. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "New Honors for 'Breaking the Waves'". Los Angeles Times. 6 January 1997. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "1st Annual Film Awards (1996)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "2009 | Categories | International Press Academy". International Press Academy. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ 23rd Saturn Awards at IMDb. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Baumgartner, Marjorie (December 27, 1996). "Fargo, You Betcha; Society of Texas Film Critics Announce Awards". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- ^ "SEFCA 1996 Winners". sefca.net. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Primal Fear (film) |

- 1996 films

- English-language films

- 1990s crime drama films

- 1990s crime thriller films

- 1990s legal films

- 1990s psychological thriller films

- 1990s thriller drama films

- American crime drama films

- American crime thriller films

- American films

- American legal drama films

- American psychological thriller films

- American thriller drama films

- American courtroom films

- Dissociative identity disorder in films

- Films scored by James Newton Howard

- Films about lawyers

- Films about religion

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on crime novels

- Films directed by Gregory Hoblit

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films set in Chicago

- Films shot in Chicago

- Films shot in West Virginia

- Films produced by Gary Lucchesi

- Legal thriller films

- American neo-noir films

- Paramount Pictures films

- Rysher Entertainment films

- Works about judgement

- Works about law enforcement

- 1996 directorial debut films

- 1996 drama films