Proletariat

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labor |

|---|

|

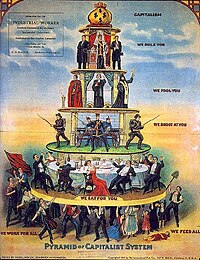

The proletariat (/ˌproʊlɪˈtɛəriət/ from Latin proletarius 'producing offspring') is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work).[1] A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philosophy considers the proletariat to be exploited under capitalism, forced to accept meagre wages in return for operating the means of production, which belong to the class of business owners, the bourgeoisie.

Marx argued that this oppression gives the proletariat common economic and political interests that transcend national boundaries, impelling them to unite and take over power from the capitalist class, and eventually to create a communist society free from class distinctions.

Roman Republic and Empire[]

The proletarii constituted a social class of Roman citizens who owned little or no property. The name presumably originated with the census, which Roman authorities conducted every five years to produce a register of citizens and their property, which determined their military duties and voting privileges. Those who owned 11,000 assēs or less fell below the lowest category for military service, and their children—prōlēs (offspring)—were listed instead of property; hence the name proletarius (producer of offspring). Roman citizen-soldiers paid for their own horses and arms, and fought without payment for the commonwealth, but the only military contribution of a proletarius was his children, the future Roman citizens who could colonize conquered territories. Officially, propertyless citizens were called capite censi because they were "persons registered not as to their property...but simply as to their existence as living individuals, primarily as heads (caput) of a family."[2][note 1]

Although included in the Comitia Centuriata (Centuriate Assembly), proletarii were the lowest class, largely deprived of voting rights.[3] Late Roman historians such as Livy vaguely described the Comitia Centuriata as a popular assembly of early Rome composed of centuriae, voting units representing classes of citizens according to wealth. This assembly, which usually met on the Campus Martius to discuss public policy, designated the military duties of Roman citizens.[4] One of the reconstructions of the Comitia Centuriata features 18 centuriae of cavalry, and 170 centuriae of infantry divided into five classes by wealth, plus 5 centuriae of support personnel called adsidui, one of which represented the proletarii. In battle, the cavalry brought their horses and arms, the top infantry class full arms and armor, the next two classes less, the fourth class only spears, the fifth slings, while the assisting adsidui held no weapons. In voting, the cavalry and top infantry class were enough to decide an issue; as voting started at the top, issues were usually decided before the lower classes voted.[5]

After the Second Punic War in 201 BC, the Jugurthine War and various conflicts in Macedonia and Asia reduced the number of Roman family farmers, and the Republic experienced a shortage of propertied citizen soldiers.[6] The Marian reforms of 107 BC extended military eligibility to the urban poor, and henceforth the proletarii, as paid soldiers, became the backbone of the army, which later served as the decisive force in the fall of the Republic and the establishment of the Empire.[7]

Modern use[]

In the early 19th century, many Western European liberal scholars — who dealt with social sciences and economics — pointed out the socio-economic similarities of the modern rapidly growing industrial worker class and the classic proletarians. One of the earliest analogies can be found in the 1807 paper of French philosopher and political scientist Hugues Felicité Robert de Lamennais. Later it was translated to English with the title "Modern Slavery".[8]

Swiss liberal economist and historian Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi was the first to apply the proletariat term to the working class created under capitalism, and whose writings were frequently cited by Karl Marx. Marx most likely encountered the term while studying the works of Sismondi.[9][10][11][12]

Marxist theory[]

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

|

Marx, who studied Roman law at the Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin,[13] used the term proletariat in his socio-political theory (Marxism) to describe a progressive working class untainted by private property and capable of revolutionary action to topple capitalism and abolish social classes, leading society to ever higher levels of prosperity and justice.

Marx defined the proletariat as the social class having no significant ownership of the means of production (factories, machines, land, mines, buildings, vehicles) and whose only means of subsistence is to sell their labor power for a wage or salary.[14] Proletarians are wage-workers, while some (though not Marx himself) distinguish salaried workers as the salariat.

Marxist theory only vaguely defines the borders between the proletariat and adjacent social classes. In the socially superior, less progressive direction are the lower petty bourgeoisie, such as small shopkeepers, who rely primarily on self-employment at an income comparable to an ordinary wage. Intermediate positions are possible, where wage-labor for an employer combines with self-employment. In another direction, the lumpenproletariat or "rag-proletariat", which Marx considers a retrograde class, live in the informal economy outside of legal employment: the poorest outcasts of society such as beggars, tricksters, entertainers, buskers, criminals and prostitutes.[15][16] Socialist parties have often argued over whether they should organize and represent all the lower classes, or only the wage-earning proletariat.

According to Marxism, capitalism is based on the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie: the workers, who own no means of production, must use the property of others to produce goods and services and to earn their living. Workers cannot rent the means of production (e.g. a factory or department store) to produce on their own account; rather, capitalists hire workers, and the goods or services produced become the property of the capitalist, who sells them at market.

Part of the net selling price pays the workers' wages (variable costs); a second part renews the means of production (constant costs, capital investment); while the third part is consumed by the capitalist class, split between the capitalist's personal profit and fees to other owners (rents, taxes, interest on loans, etc.). The struggle over the first part (wage rates) puts the proletariat and bourgeoisie into irreconcilable conflict, as market competition pushes wages inexorably to the minimum necessary for the workers to survive and continue working. The second part, called capitalized surplus value, is used to renew or increase the means of production (capital), either in quantity or quality.[17] The second and third parts are known as surplus value, the difference between the wealth the proletariat produce and the wealth they consume[18]

Marxists argue that new wealth is created through labor applied to natural resources.[19] The commodities that proletarians produce and capitalists sell are valued not for their usefulness, but for the amount of labor embodied in them: for example, air is essential but requires no labor to produce, and is therefore free; while a diamond is much less useful, but requires hundreds of hours of mining and cutting, and is therefore expensive. The same goes for the workers' labor power: it is valued not for the amount of wealth it produces, but for the amount of labor necessary to keep the workers fed, housed, sufficiently trained, and able to raise children as new workers. On the other hand, capitalists earn their wealth not as a function of their personal labor, which may even be null, but by the juridical relation of their property to the means of production (e.g. owning a factory or farmland).

Marx argued that the proletariat would inevitably displace the capitalist system with the dictatorship of the proletariat, abolishing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then developing into a communist society in which "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all".[20]

Proletarian culture[]

Marx argued that each social class had its characteristic culture and politics. The socialist states stemming from the Russian Revolution championed an official version of proletarian culture.

This was quite different from the working-class culture of capitalist countries, which tend to experience "prole drift" (proletarian drift), in which everything inexorably becomes commonplace and commodified by means of mass production, mass selling, mass communication and mass education. Examples include best-seller lists, films, and music made to appeal to the masses, and shopping malls.[21]

See also[]

- Blue-collar worker – Working-class person who performs manual labor

- Consumtariat

- Laborer

- Peasant – Pre-industrial agricultural laborer or farmer with limited land ownership

- Precariat – Class of wage-earners in a tenuous job situation close to unemployment

- Proles (Nineteen Eighty-Four) – 1949 dystopian novel by George Orwell

- Prolefeed

- Proletarianization

- Proletarian internationalism – Marxist social class concept

- Proletarian literature

- Wage slavery – Term describing dependence on wages or a salary

Notes[]

- ^ Arnold J. Toynbee, especially in his A Study of History, uses the word "proletariat" in this general sense of people without property or a stake in society. Toynbee focuses particularly on the generative spiritual life of the "internal proletariat" (those living within a given civil society). He also describes the "heroic" folk legends of the "external proletariat" (poorer groups living outside the borders of a civilization). Compare Toynbee, A Study of History (Oxford University 1934–1961), 12 volumes, in Volume V Disintegration of Civilizations, part one (1939) at 58–194 (internal proletariat), and at 194–337 (external proletariat).

References[]

- ^ proletariat. Accessed: 6 June 2013.

- ^ Adolf Berger, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society 1953) at 380; 657.

- ^ Berger, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (1953) at 351; 657 (quote).

- ^ Titus Livius (c. 59 BC – AD 17), Ab urbe condita, 1, 43; the first five books translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt as Livy, The Early History of Rome (Penguin 1960, 1971) at 81–82.

- ^ Andrew Lintott, The Constitution of the Roman Republic (Oxford University 1999) at 55–61, re the Comitia Centuriata.

- ^ Cf., Theodor Mommsen, Römisches Geschichte (1854–1856), 3 volumes; translated as History of Rome (1862–1866), 4 volumes; reprint (The Free Press 1957) at vol. III: 48–55 (Mommsen's Bk. III, ch. XI toward end).

- ^ H. H. Scullard, Gracchi to Nero. A History of Rome from 133 BC to AD 68 (London: Methuen 1959, 4th ed. 1976) at 51–52.

- ^ de Lamennais, Félicité Robert (1840). Modern Slavery. J. Watson. p. 9.

- ^ Ekins, Paul; Max-Neef, Manfred (2006). Real Life Economics. Routledge. pp. 91–93.

- ^ Ekelund Jr, Robert B.; Hébert, Robert F. (2006). A History of Economic Theory and Method: Fifth Edition. Waveland Press. p. 226.

- ^ Lutz, Mark A. (2002). Economics for the Common Good: Two Centuries of Economic Thought in the Humanist Tradition. Routledge. pp. 55–57.

- ^ Stedman Jones, Gareth (2006). "Saint-Simon and the Liberal origins of the Socialist critique of Political Economy". In Aprile, Sylvie; Bensimon, Fabrice (eds.). La France et l'Angleterre au XIXe siècle. Échanges, représentations, comparaisons. Créaphis. pp. 21–47.

- ^ Cf., Sidney Hook, Marx and the Marxists (Princeton: Van Nostrand 1955) at 13.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1887). "Chapter Six: The Buying and Selling of Labour-Power". In Frederick Engels (ed.). Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Ökonomie [Capital: Critique of Political Economy]. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Lumpenproletariat | Marxism". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Marx, Karl (February 1848). "Bourgeois and Proletarians". Manifesto of the Communist Party. Progress Publishers. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa. The Accumulation of Capital. Chapter 6, Enlarged Reproduction, http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1913/accumulation-capital/ch06.htm

- ^ Marx, Karl. The Capital, volume 1, chapter 6. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch06.htm

- ^ Marx, Karl. Critique of the Gotha Programme, I. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ch01.htm

- ^ Marx, Karl. The Communist Manifesto, part II, Proletarians and Communists http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm

- ^ Fussell, Paul (October 1992). Class, A Guide Through the American Status System. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-345-31816-9.

Further reading[]

- Blackledge, Paul (2011). "Why workers can change the world". Socialist Review. London.

364

- Hal Draper, Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, Vol. 2; The Politics of Social Classes. (New York: Monthly Review Press 1978).

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Proletariat |

| Look up proletariat in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Working class

- Socialism

- Marxism

- Marxist theory

- Measurements and definitions of poverty