Pulse diagnosis

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

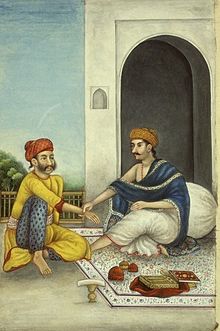

Pulse diagnosis is a diagnostic technique used in Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Mongolian medicine, Siddha medicine, traditional Tibetan medicine, and Unani. Although it once showed many positive results, it no longer has scientific legitimacy, but research continues[1] and is ill-defined in some derived text, and is subjective.[2][3]

Traditional Indian medicine (Ayurveda and Siddha-Veda)[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (December 2017) |

In Ayurveda, advocates claim that by taking a pulse examination, imbalances in the three Doshas (Vata, Pitta, and Kapha) can be diagnosed.[4] The ayurvedic pulse also claims to determine the balance of prana, tejas, and ojas.[5][6]

Ayurvedic pulse measurement is done by placing index, middle and ring finger on the wrist. The index finger is placed below the wrist bone on the thumb side of the hand (radial styloid). This index finger represents the Vata dosha. The middle finger and ring finger are placed next to the index finger and represents consequently the Pitta and Kapha doshas of the patient. Pulse can be measured in the superficial, middle, and deep levels thus obtaining more information regarding energy imbalance of the patient.[6]

Traditional Chinese medicine[]

The main sites for pulse assessment are the radial arteries in the left and right wrists, where it overlays the styloid process of the radius, between the wrist crease and extending proximal, approximately 5 cm in length (or 1.9 cun, where the forearm is 12 cun). In traditional Chinese medicine, the pulse is divided into three positions on each wrist. The first pulse closest to the wrist is the cun (inch, 寸) position, the second guan (gate, 關), and the third pulse position furthest away from the wrist is the chi (foot, 尺).

There are several systems of diagnostic interpretation of pulse findings utilised in the Chinese medicine system. Some systems (Cun Kou) utilise overall pulse qualities, looking at changes in the assessed parameters of the pulse to derive one of the traditional 29 pulse types. The traditional 29 pulse types include Floating, Soggy, Empty, Leathery, Scattered, Hollow, Deep, Firm, Hidden, Long, Surging, Short, Rapid, Hasty, Hurried, Moderate, Slow, Knotted, Full, Thready, Minute, Slippery, Choppy, Wiry, Tight, Weak, Regularly intermittent, rapid-irregular, and Stirred. They are analyzed based on several factors, including depth, speed, length, and fluid level. Some pulses are a combination of more than one factor.[7]

Other approaches focus on individual pulse positions, looking at changes in the pulse quality and strength within the position, with each position having an association with a particular body area.[8] For example, each of the paired pulse positions can represent the upper, middle and lower cavities of the torso, or are associated individually with specific organs. (For example, the small intestine is said to be reflected in the pulse at the left superficial position, and the heart at the deep position.)

Various classic texts cite different arrangements to the pairings of organs, some omitting the second organ from the pulse entirely while others show organ systems reflecting the acupuncture channels (five phase pulse associations), and another the physical organ arrangement used in Chinese herbal medicine diagnosis (Li Shi Zhen[9]). Generally, the commonly used organ associations are: first position on the left hand represents the heart and small intestine, the second, liver and gallbladder, and third the kidney yin and the bladder. On the right hand, the first position is representative of the lungs and large intestine, the second of the spleen and stomach, and the third represents the kidney yang and uterus or triple burner. The strengths and weaknesses of the positions are assessed at 3 depths each, namely fu (floating, 浮), zhong (middle, 中) and chen (deep, 沉).[10] These 9 positions are used to assess the patient diagnostically, along with the different qualities and speed of the pulse.[11]

In ancient Islamic medicine[]

Pulse diagnosis, or pulsology, was part of medicine in the medieval Islamic world. The Canon of Medicine, published in 1025, included instructions on how to analyse the pulse and from such examination, physicians considered that they could identify problems ranging from jaundice to dropsy, diphtheria, pregnancy, and anxiety.[12]

Further reading[]

- Vasant Lad, Secrets of the Pulse: The Ancient Art of Ayurvedic Pulse Diagnosis, The Ayurvedic Press; 2006 ISBN 1-883725-13-5.

- Mahesh Krishnamurthy, Nadi Pariksha - The Sacred Science of Pulse Diagnosis, Jayanthi Enterprises; 2018 ISBN 978-1-7321901-1-5.

References[]

- ^ "pulse diagnosis – Science-Based Medicine". sciencebasedmedicine.org. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- ^ Bilton, Karen; Zaslawski, Chris (August 2016). "Reliability of Manual Pulse Diagnosis Methods in Traditional East Asian Medicine: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. New York, N.Y. 22 (8): 599–609. doi:10.1089/acm.2016.0056. ISSN 1557-7708. PMID 27314975.

- ^ "Be Wary of Acupuncture, Qigong, and "Chinese Medicine"". Quackwatch. 12 January 2011. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- ^ "Under pressure - Health - Specials - smh.com.au". www.smh.com.au. 2005-05-19. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Peter Koch, December 1, 2012: Ayurvedische Pulsdiagnose

- ^ a b Lad, Vasant (2005). Secrets of the Pulse: The Ancient Art of Ayurvedic Pulse Diagnosis. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120820265.

- ^ "The 29 Pulses in Chinese Medicine (TCM) Pulse Diagnosis". Sacred Lotus. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Walsh S, King E. Pulse Diagnosis: A Clinical Guide. 2008. Edinburgh; Churchill Livingstone

- ^ Li, Shi Zhen. Lakeside Masters Study of the Pulse. 1999. Boulder; Blue Poppy Press

- ^ Hammer, Leon. Handbook of Contemporary Chinese Pulse Diagnosis. Copyright 2012.

- ^ Maciocia, Giovanni. The Foundations of Chinese Medicine, Second Edition. Copyright 2005.

- ^ Hajar, R (April 2018). "The Pulse in Medieval and Arab-Islamic Medicine: Part 2". Heart Views. 19 (2): 76–80. doi:10.4103/HEARTVIEWS.HEARTVIEWS_100_18. PMC 6219283. PMID 30505402.

- Ayurveda

- Tibetan medicine

- Traditional Chinese medicine