Rawhide Kid

| Rawhide Kid | |

|---|---|

The Rawhide Kid (Vol. 4) #1 (June 2010) | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Atlas Comics / Marvel Comics |

| First appearance | Rawhide Kid #1 (March 1955) |

| Created by | (first version) Stan Lee (writer) Bob Brown (artist) (second version) Stan Lee Jack Kirby |

| In-story information | |

| Full name | John Barton ClayJohnny Bart |

| Team affiliations | Avengers West Coast Avengers The Sensational Seven |

| Notable aliases | Johnny Clay |

| Rawhide Kid | |

| Series publication information | |

| Publisher | Atlas Comics Marvel Comics |

| Schedule | Bimonthly |

| Format | Ongoing series |

| Genre | Western |

| Publication date | (Atlas) Mar. 1955 – Sept. 1957 (Marvel) Aug. 1960 – May 1979 |

| Number of issues | 151 |

| Main character(s) | Rawhide Kid |

| Creative team | |

| Writer(s) | Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, |

| Artist(s) | Bob Brown, Jack Davis |

| Penciller(s) | Jack Kirby, Larry Lieber |

| Inker(s) | Dick Ayers, John Tartaglione |

| Collected editions | |

| Marvel Masterworks: Rawhide Kid vol. 1 | ISBN 0-7851-2117-X |

| Marvel Masterworks: Rawhide Kid vol. 2 | ISBN 0-7851-2684-8 |

The Rawhide Kid (real name: Johnny Bart, originally given as Johnny Clay) is a fictional Old West cowboy appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. A heroic gunfighter of the 19th-century American West who was unjustly wanted as an outlaw, he is one of Marvel's most prolific Western characters. He and other Marvel western heroes have on rare occasions guest-starred through time travel in such contemporary titles as The Avengers and West Coast Avengers. In two mature-audience miniseries, in 2003 and 2010, he is depicted as gay.

Publication history[]

Atlas Comics[]

The Rawhide Kid debuted in a 16-issue series (March 1955-Sept. 1957) from Marvel's 1950s predecessor, Atlas Comics.[1] Most of the covers from the series were produced by highly acclaimed artists, generally either Joe Maneely or John Severin, but also Russ Heath and Fred Kida. Interior art for the first five issues was by Bob Brown, with Dick Ayers at the reins thereafter.[2][3]

Marvel Comics[]

After a hiatus, the Rawhide Kid was revamped for what was now Marvel Comics by writer Stan Lee, penciler Jack Kirby and inker Ayers. Continuing the Atlas numbering with issue #17 (Aug. 1960),[3][4] the title now featured a diminutive yet confident, soft-spoken fast gun constantly underestimated by bullying toughs, varmints, owlhoots, polecats, crooked saloon owners and other archetypes squeezed through the prism of Lee and Kirby's anarchic imagination.[5] As in the outsized, exuberantly exaggerated action of the later-to-come World War II series Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos, The Rawhide Kid was now a freewheeling romp of energetic, almost slapstick action across cattle ranches, horse troughs, corrals, canyons and swinging chandeliers. Stringently moral, the Kid nevertheless showed a gleeful pride in his shooting and his acrobatic fight skills — never picking arguments, but constantly forced to surprise lummoxes far bigger than he was.

Through retcon, bits of and pieces of the Atlas and Silver Age characters' history meshed, so that the unnamed infant son of settlers the Clay family, orphaned by a Cheyenne raid, was raised by Texas Ranger Ben Bart on a ranch near Rawhide, Texas. Older brother Frank Clay, captured by Native Americans, eventually escaped and became a gambler, while eldest brother Joe Clay became sheriff of the town of Willow Flats; neither were in the regular cast, and each died in a guest appearance.[citation needed] Shortly after Johnny's 18th birthday, Ben Bart was murdered; Johnny, an almost preternaturally fast and accurate gunman, wounded the killers and left them to be taken into custody. A later misunderstanding between the Kid and a sheriff over a cattle rustler that the Kid wounded in self-defense led to the hero's life as a fugitive.

Kirby continued as penciler through #32 (Feb. 1963), while helping to launch the Fantastic Four, the Hulk and other iconic characters of the "Marvel revolution". He drew covers through issue #47. Issues #33-35 were drawn by EC Comics veteran Jack Davis — some of the last color comics he would draw before gaining fame at the black-and-white satirical comics magazine Mad. After several issues by Ayers, followed by a single issue by long-time Kid Colt artist Jack Keller, Larry Lieber, Lee's writer brother, began his nine-year run as the series' writer-artist, which lasted over 75 issues from 1964–1973. Lieber said in 1999,

I don't remember why I wanted to do it, particularly. I think I wanted a little more freedom. I didn't do enough of the superheroes to know whether I'd like them. What I didn't prefer was the style that was developing. It didn't appeal to me. ... Maybe there was just too much humor in it, or too much something. ... I remember, at the time, I wanted to make everything serious. I didn't want to give a light tone to it. When I did Rawhide Kid, I wanted people to cry as if they were watching High Noon or something. ... I'm a little unclear about leaving the superheroes and going to Rawhide Kid. I know that at the time I wanted — what's the expression? — a little space for myself or something, and I wanted to do a little drawing again.[6]

Rawhide Kid's full name was revealed in issue # 60 in the Letter's Column as John Barton Clay. By 1973, as superheroes became increasingly ascendant, The Rawhide Kid became primarily a reprint title, though often bearing new covers by such prominent artists as Gene Colan, Gil Kane and Paul Gulacy. It ended publication with issue #151 (May 1979). This initial volume of the series included a single annual publication, cover-titled Rawhide Kid King-Size Special (Sept. 1971).[7] As well, reprints, including many Jack Kirby-drawn stories, appeared in the 1968-1976 title The Mighty Marvel Western.

The Rawhide Kid later appeared as a middle-aged character in a four-issue miniseries, The Rawhide Kid (vol. 2)(Aug.-Nov. 1985), by writer Bill Mantlo and penciler Herb Trimpe.[8][9]

2000s treatments[]

The Rawhide Kid reappeared in the four-issue miniseries Blaze of Glory (Feb.-March 2000; published biweekly), by writer John Ostrander and artist Leonardo Manco,[10] and a 2002 four-issue sequel, Apache Skies, by the same creative team.[11]

In contrast to the character's previously depicted appearance — a small-statured, clean-cut redhead — these latter two series depicted him with shoulder-length dark hair, and wearing a slightly less stylized, more historically appropriate outfit than his classic one.

A controversial[12] five-issue miniseries, Rawhide Kid (vol. 3) (April–June 2003), titled "Slap Leather"[13][14] was published biweekly by Marvel's mature-audience MAX imprint. Here, the character was depicted as homosexual, with a good portion of the dialogue dedicated to innuendo to this effect.[15] The series, which was written by , and drawn by artist John Severin, was labeled with a "Parental Advisory Explicit Content" warning on the cover.[14] Series editor Axel Alonso said, "We thought it would be interesting to play with the genre. Enigmatic cowboy rides into dusty little desert town victimized by desperadoes, saves the day, wins everyone's heart, then rides off into the sunset, looking better than any cowboy has a right to."[16]

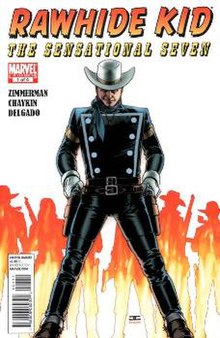

A sequel miniseries, The Rawhide Kid (vol. 4) (Aug.-Nov. 2010),[17] rendered with a subtitle on covers as Rawhide Kid: The Sensational Seven,[18] found the Kid and his posse (consisting of Kid Colt, Doc Holliday, Annie Oakley, Billy the Kid, Red Wolf and the Two-Gun Kid) track the villainous Cristo Pike after Pike and his gang kidnap Wyatt and Morgan Earp.[19] The sequel was again written by Zimmerman, with Howard Chaykin taking over as artist.[20]

Fictional character biography[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (January 2018) |

Johnny Clay was born in 1850 and orphaned as an infant, adopted by Ben Bart. In 1868 his "uncle" was murdered and he left the family ranch.[21] In 1869 he became a wanted man.[21] In 1870 he fought the Living Totem.[22] In 1872 he captured the costumed Grizzly with the help of the Two-Gun Kid.[23] He joined Kid Colt to defeat Iron Mask.[24] In 1873 he met the Avengers [25] In 1874 he met Doc Holliday. In 1875, he helped the Black Panther with Kid Colt and the Two-Gun Kid.[26] In 1876 the Rawhide Kid, Kid Colt and the Two-Gun Kid faced Red Raven, Iron Mask and the Living Totem with the help of the Avengers. In 1879 he met the Apache Kid. Subsequently, he became a performer for Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show where he remained until 1885. In 1897 he took an understudy under his tutelage.[27]

Other versions[]

Marvel Zombies[]

When a meteorite landed on Earth-483, it emitted radiation that resurrected the Rawhide Kid's corpse and all of the corpses buried in the adjacent Boot Hill as "Romero-type" zombies. The Rawhide Kid and the other reanimated gunslingers invade a nearby town, and are destroyed by Hurricane.[28]

Secret Wars[]

During the Secret Wars storyline, the Rawhide Kid appears as a member of the Thor Corps whose jurisdiction is a Wild West-themed domain of Battleworld called the Valley of Doom. He arrested that region's version of Hank Pym for illegal possession of adamantium, which led to Pym being banished to the Ultron-infested domain called Perfection.[29]

In other media[]

- The Rawhide Kid appears in Lego Marvel Super Heroes 2.[30] In a bonus mission narrated by Gwenpool that takes place in the Old West section of Chronopolis, the Rawhide Kid and Red Wolf hear that their old enemy the Living Totem is back in town putting on a one-alien show in the local saloon. After disrupting the Living Totem's show, the Rawhide Kid and Red Wolf learn that the Living Totem was raising money to build a spaceship to get back to his planet. With everything that was going on in Chronopolis, the Rawhide Kid and Red Wolf suggest to the Living Totem to seek out the Guardians of the Galaxy and ask them for a ride.

Reception[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2017) |

Comic Book Resources placed the 2000 series depiction of the Rawhide Kid as one of the superheroes Marvel wants you to forget.[31]

Collected editions[]

- Marvel Masterworks: Rawhide Kid (hardcover, Marvel Comics):

- Volume 1 (collects Rawhide Kid #17-25, (Marvel Comics 2006) ISBN 0-7851-2117-X)

- Volume 2 (collects Rawhide Kid #26-35, (Marvel Comics 2007), ISBN 0-7851-2684-8)

- Essential Rawhide Kid Volume 1 (collects Rawhide Kid #17-35, trade paperback (Marvel Comics 2011), ISBN 0-7851-6394-8)

- Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather (collects Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather #1-5, trade paperback (Marvel Comics 2003), ISBN 0-7851-1069-0; hardcover (Marvel Comics 2010), ISBN 0-7851-4362-9)

See also[]

- LGBT themes in American mainstream comics

- LGBT themes in comics

References[]

- ^ Markstein, Don. "The Rawhide Kid". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Rawhide Kid (Marvel, Atlas [Cornell Publishing Corp.] imprint, 1955 Series) at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rawhide Kid (I) (1955-1979) at The Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- ^ Rawhide Kid, The (Marvel, 1960 Series) at the Grand Comics Database. "The" as per copyrighted title in postal indicia, no "The" on cover-logo trademark.

- ^ Brevoort, Tom; DeFalco, Tom; Manning, Matthew K.; Sanderson, Peter; Wiacek, Win (2017). Marvel Year By Year: A Visual History. DK Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-1465455505.

- ^ "A Conversation with Artist-Writer Larry Lieber", conducted by former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas, Alter Ego vol. 3, #2 (Fall 1999)

- ^ Rawhide Kid Special (Marvel, 1971 Series) at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Rawhide Kid (II) (1985) at The Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- ^ Rawhide Kid (Marvel, 1985 Series) at the Grand Comics Database. "The" as per cover-logo trademark; no "The" in copyrighted title in postal indicia.

- ^ Blaze of Glory at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Apache Skies at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Paul, Ryan (2003-03-19). "Rawhide Kid #1-2". PopMatters. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ Rawhide Kid (III) (2003) at The Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rawhide Kid (Marvel, MAX imprint, 2003 Series) at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Brevoort, Tom; DeFalco, Tom; Manning, Matthew K.; Sanderson, Peter; Wiacek, Win (2017). Marvel Year By Year: A Visual History. DK Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 978-1465455505.

- ^ "The Wilde West". The Advocate. Here. February 4, 2003. p. 23. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ The Rawhide Kid (IV) at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators. "The" as per copyrighted title in postal indicia, no "The" on cover-logo trademark.

- ^ Rawhide Kid, The (Marvel, 2010) covers at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ McElhatton, Greg. Rawhide Kid: The Sensational Seven Comic Book Resources; June 11, 2010

- ^ "Preview: The Rawhide Kid #1" (Press release). Marvel Comics Group. June 3, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rawhide Kid #17, 1960

- ^ Rawhide Kid #22, 1961

- ^ Rawhide Kid #40, 1964

- ^ Kid Colt #121, 1965

- ^ Avengers #142-143, 1975

- ^ Black Panther #45-46

- ^ Rawhide Kid #1-4, 1985

- ^ Fred van Lente (w), Kano (p), Tom Palmer (i), Val Staples (col), Simon Bowland (let), Mark Paniccia and Michael Horwitz (ed). "The Dead and the Quick" Marvel Zombies 5 #1 (7 April 2010), United States: Marvel Comics

- ^ James Robinson (w), Steve Pugh and Paul Rivoche (p), Steve Pugh and Paul Rivoche (i), John Rauch and Jim Charalampidis (col), Clayton Cowles (let), Emily Shaw, Mark Paniccia and Chris Robinson (ed). Age of Ultron vs. Marvel Zombies #4 (2 September 2015), United States: Marvel Comics

- ^ Lego Marvel Super Heroes characters at IGN

- ^ Smith, Gary (20 August 2017). "15 Superheroes Marvel Wants You To Forget". CBR. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

External links[]

- The Rawhide Kid at Don Markstein's Toonopedia

- Marvel Directory: Rawhide Kid

- International Catalogue of Superheroes: Rawhide Kid

- A Guide to Marvel's Pre-FF #1 Heroes: Rawhide Kid (dead link)

- The Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- CNN.com: "Marvel Comics to unveil gay gunslinger"

- Gay League Profile

- 1955 comics debuts

- 1960 comics debuts

- 1957 comics endings

- 1979 comics endings

- Atlas Comics characters

- Atlas Comics titles

- Characters created by Bob Brown

- Characters created by Jack Kirby

- Characters created by Stan Lee

- Comics characters introduced in 1955

- Fictional gay males

- Fictional gunfighters

- Marvel Comics LGBT superheroes

- Marvel Comics titles

- Western (genre) comics

- Western (genre) comics characters