Recognition of Native American sacred sites in the United States

The neutrality of this article is disputed. (July 2012) |

The Recognition of Native American sacred sites in the United States could be described as "specific, discrete, narrowly delineated location on Federal land that is identified by an Indian tribe, or Indian individual determined to be an appropriately authoritative representative of an Indian religion, as sacred by virtue of its established religious significance to, or ceremonial use by, an Indian religion".[1] The sacred places are believed to "have their own 'spiritual properties and significance'".[2] Ultimately, Indigenous peoples who practice their religion at a particular site, they hold a special and sacred attachment to that land sacred land.

Among multiple issues regarding the human rights of Indigenous Peoples is the protection of these sacred sites. During colonization, Europeans claimed governance over the lands of numerous native tribes. After decolonization, Indigenous groups still fought federal governments to regain ownership of their ancestral lands, including the sacred sites and places. This conflict between the Indigenous groups has risen in the United States in recent years and the rights to the protection of sacred sites has been discussed through United States constitutional law and legislature.

The Religion Clauses of the First Amendment assert that the United States Congress has to separate church and state. The struggle to gain legal rights over the Glen Cove burial grounds in California is among many disputes between Indigenous groups and the federal government over sacred lands.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples[]

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted by the United Nations in 2007. The declaration emphasizes the right of Indigenous peoples, some of which include the protection of sacred sites and their religious practices. Articles 11, 12, and 25 of the Declaration specifically addresses these rights.

Article 11[]

Article 11 of the Declaration states:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature[3]

- States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs.[3]

Article 12[]

Article 12 of the Declaration States:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practise, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the right to the repatriation of their human remains.[3]

- States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned.[3]

Article 25[]

Article 25 of the Declaration states:

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard.[3]

Applying the United States Legal System[]

Religion Clauses[]

Indigenous peoples in the United States argued that they have the right to protect sacred sites on the grounds of religious freedom. The Religion Clauses of the First Amendment have been two main documents discussed in the dispute of sacred sites protection.[4]

Free Exercise Clause & Establishment Clause[]

The Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause prevents the United States federal government from establishing a religion by emphasizing the separation of church and state. However, the basis of the Establishment Clauses causes a problem with regards of the protection of religious practices of religious liberties by the federal government.[5]

Article VI of United States Constitution[]

While the Religious Clause may puts limits on the actions of the federal government with regards to sacred sites protection, Article Six of United States Constitution require Congress to treat "’Indian affairs as a unique area of federal concern’".[6] Any legal relationship between both parties is treated with special consideration in the basis that Indigenous peoples have become dependent on the United States government after the land was taken from them.[6] As John R. Welch et al. states, "the government 'has charged itself with moral obligations of the highest responsibility and trust'".[6] The federal government has a responsibility to maintain the agreements it made with the Indigenous peoples through the treaties. The federal government should "manage Indian trust lands and their bounties in the best interests of beneficiaries".[6]

American Indian Religious Freedom and Restoration Act[]

The American Indian Freedom and Restoration Act, or the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), was passed by congress in 1978. The act was passed to recognize Indigenous people's religious practices by not limiting access to sacred sites.[2][4] The AIRF also obliges federal agencies to administer laws to "evaluate their policies in consultation" with Indigenous groups to assure that their religious practices are protected.[2] Nonetheless, Arizona Democratic Representative Morris K. Udall who cosponsor of AIRFA asserted that the Act does "not create legal rights" and "'depends on Federal administrative good will'" for it to be applied.[4] Consequently, Indigenous groups are not able to effectively use AIRFA in their fight against public land management agencies.

Religious Freedom Restoration Act[]

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) prohibits the federal government from restricting or burdening a person's exercise of religion. Under the RFRA, a plaintiff can present a case by showing that the federal government's actions burdens his ability to exercise his religion. Still, although the law is not a procedural law and protects the free exercise of minority religion, it does not protect religious activities conflicting with government's land use[2]

National Environmental Policy Act[]

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is a national policy that promotes better environmental conditions by preventing the government from making damaging the environment. This Act relates to the sacred sites protection because it promotes and encourage a "harmonious" relationship between humans and the environment Furthermore, because this Act is a procedural law, those who bring a suit to the law must "allege a legal flaw in the process the agency followed to comply with NEPA such that the agency's final decision was reached without a complete understanding of the true effects of the action on the quality of the environment.[2]

National Historic Preservation Act[]

The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) is procedural law that implements "a program for preservation of historic properties across the United States for reasons including the ongoing loss and alteration of properties important to the nation's heritage and to orient the American people to their cultural and historical foundations".[2]

Executive Order 13007[]

On May 24, 1996, President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 13007. Under this order, executive branch agencies are required to: "(1) accommodate access to and ceremonial use of Indian sacred sites by religious practitioners and (2) avoid adversely affecting the physical integrity of such sites".[1] This order holds management of Federal lands of taking the appropriate procedures to ensure that Indigenous peoples governments are involved in actions involving sacred sites.

Glen Cove (Ssogoréate) Sacred Burial Sites[]

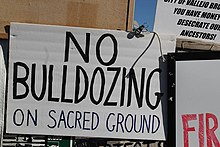

Glen Cove, also known as Sogorea Te or Ssogoréate, is located in Vallejo, California and is a ceremonial and burial ground for native tribes living near the area for over 3,500 years.[7] These tribes include the Ohlone, Patwin, Miwok, Yokuts, and Wappo. The Greater Vallejo Recreation District (GVRD)and the City of Vallejo wanted to turn the burial ground into a public park since 1988. The construction on the site requires removing the burials and sacred objects. The affected Indigenous tribes fought against the developing the land, claiming that doing so is a violation of their human and religious rights. They insist that the site means more to them than the members of the public, saying, "It is one of the few surviving remnants of our history on this land."[8]

In protest of the GVRD development, The Protect Glen Cove Committee and the Board of Directors of Sacred Sites Protection (SSP&RIT) called for Indigenous activists to assemble at Glen Cove. Beginning April 14, 2011, Indigenous tribes and supporters began occupying the area by organizing daily spiritual gatherings and ceremonies.[9]

On July 19, 2011, after 98 days of occupation and spiritual ceremonies, the Committee to Protect Glen Cove announced that the Indigenous tribes have won the jurisdiction over the land. The Yocha Dehe and Cortina tribes established a cultural easement and settlement agreement, which grants the tribes "legal oversight in all activities taking place on the sacred burial grounds of Sogoreate/Glen Cove".[10]

See also[]

- Arizona Snowbowl, See the sections, "Development controversy" & "2011 protests"

- Devils Tower National Monument

- Sogorea Te Land Trust

References[]

- ^ a b Clinton, Bill (1996). "Executive Order 13007--Indian sacred sites". Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents. 32 (21): 942.

- ^ a b c d e f Ruscavage-Barz, Samantha (2007). "The Efficacy of State Law in Protecting Native American Sacred Places: A Case Study of the Paseo Del Norte Extension". Natural Resources Journal. 47 (4): 971.

- ^ a b c d e United Nations (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- ^ a b c Linge, George (2000). "Ensuring the Full Freedom of Religion on Public Lands: Devils Tower and the Protection of Indian Sacred Sites". Environmental Affairs. 27 (307): 307–339.

- ^ Brownstein, Alan (2011). "The Religion Clauses as Mutually Reinforcing Mandates: Why the Arguments for Rigorously Enforcing the Free Exercise Clause and Establishment Clause Are Stronger When Both Clauses Are Taken Seriously". Cardozo Law Review. 32 (5): 1702.

- ^ a b c d Welch, John R.; Riley, Ramon; Michael V. Nixon (2009). "Discretionary Desecration: Dzil Nhaa Si An (Mount Graham) and Federal Agency Decisions Affecting American Indian Sacred Sites". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 33 (4): 32. doi:10.17953/aicr.33.4.2866316711817855.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "About".

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ http://protectglencove.org/2011/easement-press-release/[dead link]

External links[]

- Protect Sacred Sites Indigenous People, One Nation

- Suzan Shown Harjo's Statement for UN Special Rapporteur James Anaya

- Sacred Site Faces Legalized Desecration From Arizona Snowbowl Wastewater

- Protecting Native American Sacred Sites

- The Significance of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Sacred Sites Protection And Rights of Indigenous Tribes

- U.S. Should Return Stolen Sacred Lands, U.N. Special Rapporteur James Anaya says that stolen lands to Indigenous communities.

- Religious places of the indigenous peoples of North America