Reform Club

| Reform Club | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Italian Renaissance |

| Address | 104 Pall Mall London, SW1 |

| Coordinates | 51°30′24″N 0°08′01″W / 51.506785°N 0.133625°W |

| Groundbreaking | 1837 |

| Completed | 1841 |

| Landlord | Crown Estate Commissioners |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Sir Charles Barry |

| Civil engineer | Thomas Grissell & Morton Peto |

| Main contractor | Grissell & Peto |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Reform Club is a private members' club on the south side of Pall Mall in central London, England. As with all of London's original gentlemen's clubs, it comprised an all-male membership for decades, but it was one of the first all-male clubs to change its rules to include the admission of women on equal terms in 1981. Since its founding in 1836, the Reform Club has been the traditional home for those committed to progressive political ideas, with its membership initially consisting of Radicals and Whigs. However, it is no longer associated with any particular political party, and it now serves a purely social function.

"The Reform" (as it is known in common parlance) currently enjoys extensive reciprocity with similar clubs around the world. It attracts a significant number of foreign members, such as diplomats accredited to the Court of St James's. Of the current membership of around 2,700, some 500 are "overseas members", and over 400 are women.[1]

The Reform maintains reciprocity with many notable clubs around the world, among them The Gridiron Club (Oxford University), the Metropolitan Club (Washington, D.C.), the Jonathan Club of Los Angeles, the Lotos Club of New York City and the Cercle de l'Union interalliée in Paris.

History[]

19th century[]

The club was founded on 2 February 1836[2] by Edward Ellice, Member of Parliament (MP) for Coventry and Whig Whip, whose riches came from the Hudson's Bay Company but whose zeal was chiefly devoted to securing the passage of the Reform Act 1832. This new club, for members of both Houses of Parliament, was intended to be a forum for the radical ideas which the First Reform Bill represented: a bastion of liberal and progressive thought that became closely associated with the Liberal Party, who largely succeeded the Whigs in the second half of the 19th century.[citation needed]

Brooks's Club, the headquarters of the old Whig aristocracy, was neither able nor prepared to open its doors to a flood of new men, so preliminary meetings were held at Ellice's house to plan a much larger club, which would promote 'the social intercourse of the reformers of the United Kingdom'. In the 19th century, any Liberal Party MP or Peer crossing the floor, to join or work with another party, was expected to resign as a member.[citation needed]

Between 1890 and 1914 8 per cent of the club's membership had ties to the banking sector, some even holding directorships. Club members like Bram Stoker and Henry Irving mingled with Liberal bankers from prominent families like the Rothschilds and Goldschmidts.

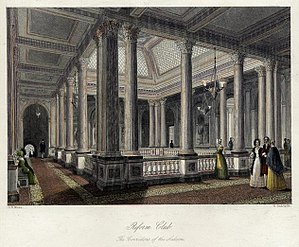

The Reform Club's building was designed by renowned architect Sir Charles Barry[3] and contracted to builders Grissell & Peto. Construction began in 1837 and was finished in 1841. This new club was built on palatial lines, the design being based on the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, and its Saloon in particular is regarded as the finest of all London's clubs. The Reform was among the first senior London clubs to provide bedrooms (known as chambers), and its library contains over 75,000 books, mostly of a political, historical and biographical nature; customarily, members donate a copy of any book they write to the club's library, ever increasing its stock.[citation needed]

The Reform was known for the quality of its cuisine, its first chef being Alexis Soyer, the first celebrity chef. It continues to offer meals in its dining room, known as the 'Coffee Room'.[citation needed]

Until the decline of the Liberal Party in the early 20th century, it was de rigueur for Liberal MPs and Peers to be members of the Reform Club, being regarded as an unofficial party headquarters. However, in 1882, the National Liberal Club was established under William Ewart Gladstone's chairmanship, designed to be more "inclusive" towards Liberal grandees and activists throughout the UK.[citation needed]

20th century[]

After the Second World War and with the old Liberal Party's further decline, the club increasingly drew its membership from civil servants,[4] not least those from the Treasury, as well as Foreign Office officials, who also frequent the neighbouring Travellers Club.[citation needed]

The club maintains a comprehensive list of guest speakers throughout the year – for example, Government Ministers Nick Clegg and Theresa May (2011), Archbishop John Sentamu (2012), and Ambassadors Liu Xiaoming (2013), as well as Dr Alexander Yakovenko and Sylvie Bermann (2014).[citation needed]

Today the Reform Club (of which Prince Charles and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall are honorary members) no longer represents any particular political viewpoint, being an impartial and purely social venue.[citation needed]

Literary associations[]

Besides having had many distinguished members from the literary world, including William Makepeace Thackeray and Arnold Bennett, the Reform played a role in some significant events, such as the feud between Oscar Wilde's friend and literary executor Robbie Ross and Wilde's ex-lover Lord Alfred Douglas. In 1913, after discovering that Lord Alfred had taken lodgings in the same house as himself with a view to stealing his papers, Ross sought refuge at the club, from where he wrote to Edmund Gosse, saying that he felt obliged to return to his rooms "with firearms".[5] Ross had been elected a member in 1899, and it was also at the club that he had entertained Wilde's son Cyril to lunch, only a few years before the latter was killed by enemy fire during the First World War.[citation needed]

Harold Owen, the brother of Wilfred Owen, called on Siegfried Sassoon at the Reform after Wilfred's death,[6] and Sassoon himself wrote a poem entitled "Lines Written at the Reform Club", which was printed for members at Christmas 1920.[7] Wilfred Owen, though not himself a member, lunched at the club several times in the company of Sassoon and Sir Roderick Meiklejohn.[citation needed]

Appearances in popular culture and literature[]

The Reform Club appears in Anthony Trollope's novel Phineas Finn (1867). This eponymous main character becomes a member of the club and there acquaints Liberal members of the House of Commons, who arrange to get him elected to an Irish parliamentary borough. The book is one of the political novels in the Palliser series, and the political events it describes are a fictionalized account of the build-up to the Second Reform Act (passed in 1867) which effectively extended the franchise to the working classes.[citation needed]

The club also appears in Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days (published in 1872, as a novel in 1873); the protagonist, Phileas Fogg, is a member of the Reform Club who sets out to circumnavigate the world on a bet from his fellow members, beginning and ending at the club.[citation needed]

Michael Palin, following his fictional predecessor, also began and ended his televised journey around the world in 80 days at the Reform Club. At the time, the Reform Club, like other London clubs since the 1950s, went through a phase of stipulating a dress code requiring gentlemen to wear a jacket and tie; Palin had not packed a tie, and he was not permitted to enter the building to complete his journey as had been his intention, so his trip ended on the steps outside.

The Reform Club was the location of a photo shoot featuring Paula Yates for the 1979 summer issue of Penthouse.[8]

Victorian publisher Norman Warne is depicted visiting the Reform Club in the 2006 film Miss Potter.[citation needed]

The club has been used as a location in a number of films, including the fencing scene in the 2002 James Bond movie Die Another Day, The Quiller Memorandum (1966), The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970), Lindsay Anderson's O Lucky Man! (1973), The Avengers (1998), Nicholas Nickleby (2002), Quantum of Solace (2008) and Sherlock Holmes (2009). It has also been used as the lobby of the Dolphin Hotel in the film adaptation of Stephen King's short story "1408."

In the 1982 BBC television adaptation of Smiley's People, based on the Cold War spy thriller by John le Carré, the titular character visits the Reform Club at the start of the third episode, spending an extended period of time in the club's library.[citation needed]

The Reform Club was used as a meeting place for MI operatives in Part 3, Chapter 1, p. 83ff of Graham Greene's spy novel The Human Factor (1978, Avon Books, ISBN 0-380-41491-0) and for a scene with Hugh Bonneville in the 2014 film Paddington. Greene also sets a lunch between the protagonist, Jim Baxter, and his biological father, who is a member, in the Reform Club in his final novel, The Captain and the Enemy.[citation needed]

The Reform Club and Victorian era celebrity chef Alexis Soyer play pivotal roles in MJ Carter's mystery novel The Devil's Feast (2016, Fig Tree, ISBN 978-0-241-14636-1).[citation needed]

The Reform Club features in Christopher Nolan's Tenet when it is visited by the protagonist.

Notable members[]

- John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair

- Donald Adamson

- H. H. Asquith

- Sir David Attenborough

- William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp

- Hilaire Belloc

- Arnold Bennett

- William Beveridge

- Stewart Binns

- Rt Hon Charles Booth

- Dame Margaret Booth

- Baroness Boothroyd

- Mihir Bose

- John Bright

- Henry Brougham

- Michael Brown, former Conservative MP

- Guy Burgess

- Donald Cameron of Lochiel

- Sir Menzies Campbell

- Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman

- Samuel Carter

- Joseph Chamberlain

- Andrew Carnegie

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Sir Winston Churchill, who resigned in 1913 in protest at the blackballing of a friend, Baron de Forest

- Richard Cobden

- Albert Cohen

- Professor Martin Daunton

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

- Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall

- Baroness Dean of Thornton-le-Fylde

- Sir Charles Dilke

- John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham

- Edward Ellice

- Lord Falconer

- Garret FitzGerald

- Edward Morgan Forster

- William Ewart Gladstone

- Baroness Greengross

- Sir William Harcourt

- Lord Hattersley

- Friedrich Hayek

- Nick Hewer

- Barbara Hosking

- Sir Michael Howard

- Sir Bernard Ingham

- Sir Henry Irving

- Henry James

- Sir John Jardine

- Lord Jenkins of Hillhead

- William, Earl Jowitt

- Ruth Lea

- David Lloyd George, who resigned with Churchill over Baron de Forest's blackballing

- Professor Sir Ravinder Maini

- Dame Mary Marsh

- José Guilherme Merquior

- James Moir

- James Montgomrey, a founding member

- Lord Morgan

- Sir Derek Morris

- Baroness Nicholson

- Lord Noel-Buxton

- Daniel O'Connell

- Barry Edward O'Meara

- David Omand

- Viscount Palmerston

- Dame Stella Rimington

- Frederick Robinson, 2nd Marquess of Ripon

- Bertram Fletcher Robinson

- Curtis Roosevelt

- Brian Roper

- Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

- Viscount Runciman

- Lord John Russell

- Paul Scofield

- Viscount Simon

- George Smith

- Sir Martin Sorrell

- Very Rev Victor Stock

- Sir Edward Sullivan

- Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex

- Professor Alan M. Taylor

- Dame Kiri Te Kanawa

- William Makepeace Thackeray

- William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

- Jeremy Thorpe

- Sir David Walker

- Chaim Weizmann

- H. G. Wells

- Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster

- Dame Jo Williams

- Tony Wright, former Labour MP

See also[]

References[]

- ^ www.evolvingmedia.co.uk, Bob Twells – Evolving Media -. "Reform Club". www.reformclub.com. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Reform Club official website". Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Pall Mall; Clubland Old and New London: Volume 4 (pp. 140–164)". british-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Walker, Tim (18 October 2011). "Polly Toynbee's man makes a meal of his expenses". Telegraph. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Maureen Borland, Wilde's Devoted Friend: a Life of Robert Ross (1990), p. 201.

- ^ Christian Major, "Sassoon's London: the Reform Club", Siegfried's Journal, no 12 (July 2007), pp. 5–13.

- ^ Russell Burlingham & Roger Billis, Reformed Characters: The Reform Club in History and Literature (2005), p. 34.

- ^ The Milwaukee Journal – 23 July 1979.

Further reading[]

- Burlingham, Russell; Billis, Roger (2005). Reformed Characters. The Reform Club in History and Literature. An Anthology with Commentary. London: Reform Club.

- Escott, T. H. S. (1914). Club Makers and Club Members. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Fagan, Louis (1887). The Reform Club 1836–1886: Its Founders and its Architect. London: Reform Club.

- Lejeune, Anthony; Lewis, Malcolm (1979). The Gentlemen's Clubs of London. London: Wh Smith Pub. ISBN 0-8317-3800-6.

- Lejeune, Anthony (2012). The Gentlemen's Clubs of London. London: Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-906768-20-1.

- Mordaunt Crook, J. (1973). The Reform Club. London: Reform Club.

- Sharpe, Michael (1996). The Political Committee of the Reform Club. London: Reform Club. ISBN 0-9503053-2-4.

- Thévoz, Seth Alexander (2018). Club Government: How the Early Victorian World was Ruled from London Clubs. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78453-818-7.

- Urbach, Peter (1999). The Reform Club: Some Twentieth Century Members - A Photographic Collection. London: Reform Club.

- Van Leeuwen, Thomas A P (2020) [2017]. The Magic Stove: Barry, Soyer and The Reform Club or How a Great Chef Helped to Create a Great Building. Amsterdam/Paris: Les Editions du Malentendu/ Jap Sam Books. ISBN 978-90-826690-0-8.

- Woodbridge, George (1978). The Reform Club 1836–1978: A History from the Club's Records. London: Clearwater. ISBN 0-9503053-1-6.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reform Club. |

- Reform Club website

- Survey of London's entry on the Club

- "The Reform Club: Architecture and the Birth of Popular Government", lecture by Peter Marsh and Paul Vonberg at Gresham College, 25 September 2007 (available for MP3 and MP4 download)

- Reform Club library pamphlets

- Mary Evans Picture Library – The Club's collection of caricatures

- CBC.CA Paul Kennedy's audio tour of the Club, broadcast in February 2011

- Gentlemen's clubs in London

- Grade I listed buildings in the City of Westminster

- 1836 establishments in the United Kingdom

- Grade I listed clubhouses

- Jules Verne

- Organisations based in London with royal patronage

- Charles Barry buildings