Repatriation (cultural property)

Repatriation is the return of cultural property, often referring to ancient or looted art, to their country of origin or former owners (or their heirs). The disputed cultural property items are physical artifacts of a group or society that were taken by another group, usually in an act of looting, whether in the context of imperialism, colonialism or war. The contested objects vary widely and include sculptures, paintings, monuments, objects such as tools or weapons for purposes of anthropological study, and human remains.

Background[]

War and looting[]

Ancient world[]

War and the subsequent looting of defeated peoples has been common practice since ancient times. The stele of King Naram-Sin of Akkad, which is now displayed in the Louvre Museum in Paris, is one of the earliest works of art known to have been looted in war. The stele commemorating Naram-Sin's victory in a battle against the Lullubi people in 2250 BCE was taken as war plunder about a thousand years later by the Elamites who relocated it to their capital in Susa, Iran. There, it was uncovered in 1898 by French archaeologists.[1]

The Palladion was the earliest and perhaps the most important stolen statue in western literature.[2] The small carved wooden statue of an armed Athena served as Troy's protective talisman, which is said to have been stolen by two Greeks who secretly smuggled the statue out of the Temple of Athena. It was widely believed in antiquity that the conquest of Troy was only possible because the city had lost its protective talisman. This myth illustrates the sacramental significance of statuary in Ancient Greece as divine manifestations of the gods that symbolized power and were often believed to possess supernatural abilities. The sacred nature of the statues is further illustrated in the supposed suffering of the victorious Greeks afterward, including Odysseus, who was the mastermind behind the robbery.[2]

According to Roman myth, Rome was founded by Romulus, the first victor to dedicate spoils taken from an enemy ruler to the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius. In Rome's many subsequent wars, blood-stained armor and weaponry were gathered and placed in temples as a symbol of respect toward the enemies' deities and as a way to win their patronage.[3] As Roman power spread throughout Italy where Greek cities once reigned, Greek art was looted and ostentatiously displayed in Rome as a triumphal symbol of foreign territories brought under Roman rule.[3] However, the triumphal procession of Marcus Claudius Marcellus after the fall of Syracuse in 211 is believed to have set a standard of reverence to conquered sanctuaries as it engendered disapproval by critics and a negative social reaction.[4]

According to Pliny the Elder, the Emperor Augustus was sufficiently embarrassed by the history of Roman plunder of Greek art to return some pieces to their original homes.[5]

18th and 19th centuries[]

The Napoleonic looting of art was a series of confiscations of artworks and precious objects carried out by the French army or French officials in the territories of the First French Empire, including the Italian peninsula, Spain, Portugal, the Low Countries, and Central Europe. The looting continued for nearly 20 years, from 1797 to the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[6]

After Napoleon’s defeat, some of the looted artworks were returned to their country of origin, among them the Lion and the Horses of Saint Mark, that were repatriated to Venice. But many other artworks remained in French museums, like the Louvre museum, the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris or other collections in France.[7]

20th and 21st centuries[]

One of the most infamous cases of esurient art plundering in wartime was the Nazi appropriation of art from both public and private holdings throughout Europe and Russia. The looting began before World War II with illegal seizures as part of a systematic persecution of Jews, which was included as a part of Nazi crimes during the Nuremberg Trials.[8] During World War II, Germany plundered 427 museums in the Soviet Union and ravaged or destroyed 1,670 Russian Orthodox churches, 237 Catholic churches and 532 synagogues.[9]

A well-known recent case of wartime looting was the plundering of ancient artifacts from the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad at the outbreak of the war in 2003. Although this was not a case in which the victors plundered art from their defeated enemy, it was result of the unstable and chaotic conditions of war that allowed looting to happen and which some[who?] would argue was the fault of the invading US forces.

Archaeologists and scholars criticized the US military for not taking the measures to secure the museum, a repository for a myriad of valuable ancient artifacts from the ancient Mesopotamian civilization.[10] In the several months leading up to the war, scholars, art directors, and collector met with the Pentagon to ensure that the US government would protect Iraq's important archaeological heritage, with the National Museum in Baghdad being at the top of the list of concerns.[11] Between April 8, when the museum was vacated and April 12, when some of the staff returned, an estimated 15,000 items and an additional 5,000 cylinder seals were stolen.[12] Moreover, the National Library was plundered of thousands of cuneiform tablets and the building was set on fire with half a million books inside; fortunately, many of the manuscripts and books were preserved.[11] A US task force was able to retrieve about half of the stolen artifacts by organizing and dispatching an inventory of missing objects and by declaring that there would be no punishment for anyone returning an item.[12] In addition to the vulnerability of art and historical institutions during the Iraq war, Iraq's rich archaeological sites and areas of excavated land (Iraq is presumed to possess vast undiscovered treasures) have fallen victim to widespread looting.[13] Hordes of looters disinterred enormous craters around Iraq's archaeological sites, sometimes using bulldozers.[14] It is estimated that between 10,000 and 15,000 archaeological sites in Iraq have been despoiled.[13]

Modern imperialism and looting[]

The scale of plundering during Napoleon's French Empire was unprecedented in modern history with the only comparable looting expeditions taking place in ancient Roman history.[15] In fact, the French revolutionaries justified the large-scale and systematic looting of Italy in 1796 by viewing themselves as the political successors of Rome, in the same way that ancient Romans saw themselves as the heirs of Greek civilization.[16] They also supported their actions with the opinion that their sophisticated artistic taste would allow them to appreciate the plundered art.[17] Napoleon's soldiers crudely dismantled the art by tearing paintings out of their frames hung in churches and sometimes causing damage during the shipping process. Napoleon's soldiers appropriated private collections and even the papal collection.[18] Of the most famous artworks plundered included the Bronze Horses of Saint Mark in Venice and the Laocoön and His Sons in Rome (both since returned), with the later being considered the most impressive sculpture from antiquity at the time.

The Laocoön had a particular meaning for the French, because it was associated with a myth in connection to the founding of Rome.[19] When the art was brought into Paris, the pieces arrived in the fashion of a triumphal procession modeled after the common practice of ancient Romans.[18]

Napoleon's extensive plunder of Italy was criticized by such French artists as Antoine-Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy (1755–1849), who circulated a petition that gathered the signatures of fifty other artists.[20] With the founding of the Louvre Museum in Paris in 1793, Napoleon's aim was to establish an encyclopedic exhibition of art history, which later both Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler would attempt to emulate in their respective countries.[16]

Napoleon continued his art conquests in 1798 when he invaded Egypt in an attempt to safeguard French trade interests and to undermine Britain's access to India via Egypt. His expedition in Egypt is noted for the 167 "savants" he took with him including scientists and other specialists equipped with tools for recording, surveying and documenting ancient and modern Egypt and its natural history.[21] Among other things, the expedition discoveries included the Rosetta Stone and the Valley of the Kings near Thebes. The French military campaign was short-lived and unsuccessful and the majority of the collected artifacts (including the Rosetta Stone) were seized by British troops, ending up in the British Museum. Nonetheless, the information gathered by the French expedition was soon after published in the several volumes of Description de l'Égypte, which included 837 copperplate engravings and over 3,000 drawings. In contrast to the disapproving public reaction to the looting of Italian works of art, the appropriation of Egyptian art saw widespread interest and fascination throughout Europe, inciting a phenomenon which came to be called "Egyptomania".[22]

A notable consequence of looting is its ability to hinder contemporary repatriation claims of cultural property to a country or community of origin. A process that requires proof of theft of an illegal transaction, or that the object originated from a specific country, can be difficult to provide if the looting and subsequent movements or transactions were undocumented.[23] For example, in 1994 the British Library acquired Kharosthi manuscript fragments and has since refused to return them unless their origin could be identified (Afghanistan, Pakistan, or Tajikistan), which the library itself was unsure of.[23][24]

Demands for restitution[]

A precedent for art repatriation was set in Roman antiquity when Cicero prosecuted Verres, a senate member and illegal appropriator of art. Cicero's speech influenced Enlightenment European thought and had an indirect impact on the modern debate about art repatriation.[25] Cicero's argument uses military episodes of plunder as "case law" and expresses certain standards when it comes to appropriating cultural property of another people.[26] Cicero makes a distinction between public and private uses of art and what is appropriate for each and he also asserts that the primary purpose of art is religious expression and veneration. He also sets standards for the responsibilities of imperial administration abroad to the code of ethics surrounding the collection of art from defeated Greece and Rome in wartime. Later, both Napoleon and Lord Elgin would be likened to Verres in condemnations of their plundering of art.[27]

Art was repatriated for the first time in modern history when Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington returned to Italy art that had been plundered by Napoleon, after his and Marshal Blücher's armies defeated the French at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.[22] This decision contrasted sharply to a long-held tradition to the effect that "to the victors go the spoils."[22] This is remarkable considering that in the battle of Waterloo alone, the financial and human costs were colossal; the decision to not only refrain from plundering France but to repatriate France's prior seizures from the Netherlands, Italy, Prussia, and Spain, was extraordinary.[28] Moreover, the British paid for the restitution of the papal collection to Rome because the Pope could not finance the shipping himself.[29] When British troops began packing up looted art from the Louvre, there was a public outcry in France. Crowds reportedly tried to prevent the taking of the Horses of Saint Mark and there were throngs of weeping ladies outside the Louvre Museum.[30] Despite the unprecedented nature of this repatriation effort, there are recent estimations that only about 55 percent of what was taken was actually repatriated: the Louvre Director at the time, Vivant Denon, had sent out many important works to other parts of France before the British could take them.[31] Wellington viewed himself as representing all of Europe's nations and he believed that the moral decision would be to restore the art in its apparently proper context.[32] In a letter to Lord Castlereagh he wrote:

The Allies then, having the contents of the museum justly in their power, could not do otherwise than restore them to the countries from which, contrary to the practice of civilized warfare, they had been torn during the disastrous period of the French revolution and the tyranny of Bonaparte. ... Not only, then, would it, in my opinion, be unjust in the Sovereigns to gratify the people of France on this subject, at the expense of their own people, but the sacrifice they would make would be impolitic, as it would deprive them of the opportunity of giving the people of France a great moral lesson.

— Excerpt from letter of Wellington to Viscount Castlereagh, K.G., Paris, September 23, 1815[30]

Wellington also forbade pilfering among his troops as he believed that it led to the lack of discipline and distraction from military duty. He also held the view that winning support from local inhabitants was an important break from Napoleon's practices.[33]

The great public interest in art repatriation helped fuel the expansion of public museums in Europe and launched museum-funded archaeological explorations. The concept of art and cultural repatriation gained momentum through the latter decades of the twentieth century and began to show fruition by the end of the century when key works were ceded back to claimants.

Legal issues[]

National government laws[]

United States[]

In 1863 US President Abraham Lincoln summoned Francis Lieber, a German-American jurist and political philosopher, to write a legal code to regulate Union soldiers' behavior toward Confederation prisoners, noncombatants, spies and property. The resulting General Orders No.100 or the Lieber Code, legally recognized cultural property as a protected category in war.[34] The Lieber Code had far-reaching results as it became the basis for the Hague Convention of 1907 and 1954 and has led to Standing Rules of Engagement (ROE) for US troops today.[35] A portion of the ROE clauses instruct US troops not to attack "schools, museums, national monuments, and any other historical or cultural sites unless they are being used for a military purpose and pose a threat".[35]

In 2004 the US passed the Bill HR1047 for the Emergency Protection for Iraq Cultural Antiquities Act, which allows the President authority to impose emergency import restrictions by Section 204 of the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CCIPA).[36] In 2003, Britain and Switzerland put into effect statutory prohibitions against illegally exported Iraqi artifacts. In the UK, the Dealing in Cultural Objects Bill was established in 2003 that prohibited the handling of illegal cultural objects.

United Kingdom[]

Repatriation in the UK has been highly debated in recent years, however there is still a lack of formal national legislation that expressly outlines general claims and repatriation procedures.[37] As a result, guidance on repatriation stems from museum authority and government guidelines, such as the Museum Ethnographers' Group (1994) and the Museums Association Guidelines on Restitution and Repatriation (2000). This means that individual museum policies on repatriation can vary significantly depending on the museum's views, collections and other factors.[38]

The repatriation of human remains is governed by the Human Tissue Act 2004. However, the Act itself does not create guidelines on the process of repatriation, it merely states it is legally possible for museums to do so.[37] This again highlights that successful repatriation claims in the UK are dependent on museum policy and procedure. One example includes the British Museum's policy on the restitution of human remains.[39]

International conventions[]

The Hague Convention of 1907 aimed to forbid pillaging and sought to make wartime plunder the subject of legal proceedings, although in practice the defeated countries did not gain any leverage in their demands for repatriation.[9] The Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict took place in the wake of widespread destruction of cultural heritage in World War II is the first international treaty of a worldwide vocation focusing exclusively on the protection of cultural heritage in the event of armed conflict.

Irini Stamatoudi suggests that the 1970 UNESCO convention on prohibiting and preventing illicit imports and exports and the 1995 UNIDROIT convention on stolen or illegally exported cultural objects are most important international conventions related to cultural property law.[40]

UNESCO[]

The 1970 UNESCO Convention against Illicit Export under the Act to implement the Convention (the Cultural Property Implementation Act) allowed for stolen objects to be seized, if there were documentation of it in a museum or institution of a state party, the convention also encouraged member states to adopt the convention within their own national laws.[41] The following agreement in 1972 promoted world cultural and natural heritage.[42]

The 1978 UNESCO Convention strengthened existing provisions; the Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its countries of origin or its restitution in case of illicit appropriation was established. It consists of 22 members elected by the General Conference of UNESCO to facilitate bilateral negotiations for the restitution of "any cultural property which has a fundamental significance from the point of view of the spiritual values and cultural heritage of the people of a Member State or Associate Member of UNESCO and which has been lost as a result of colonial or foreign occupation or as a result of illicit appropriation".[43] It was also created to "encourage the necessary research and studies for the establishment of coherent programmes for the constitution of representative collections in countries, whose cultural heritage has been dispersed".[43]

In response to the Iraqi National Museum looting, UNESCO Director-General, Kōichirō Matsuura convened a meeting in Paris on April 17, 2003, to assess the situation and coordinate international networks in order to recover the cultural heritage of Iraq. On July 8, 2003, Interpol and UNESCO signed an amendment to their 1999 Cooperation Agreement in the effort to recover looted Iraqi artifacts.[44]

UNIDROIT[]

The UNIDROIT (International Institute for the Unification of Private Law) Convention on Stolen or Illicitly Exported Cultural Objects of 1995 called for the return of illegally exported cultural objects.[45]

Political issues[]

Colonialism and identity[]

From early on, the field of archaeology was deeply involved in political endeavors and in the construction of national identities. This early relationship can be seen during the Renaissance and the proto-Italian reactions against the High Gothic movement, but the relationship became stronger during 19th century Europe when archaeology became institutionalized as a field of study furnished by artifacts acquired during the New Imperialism era of European colonialism.[46] Colonialism and the field of archaeology mutually supported one another as the need to acquire knowledge of ancient artifacts justified further colonial dominance.

As further justification for colonial rule, the archaeological discoveries also shaped the way European colonialists identified with the artifacts and the ancient people who made them. In the case of Egypt, colonial Europe's mission was to bring the glory and magnificence of ancient Egypt closer to Europe and incorporate it into knowledge of world history, or better yet, use European history to place ancient Egypt in a new spotlight.[47] With the archaeological discoveries, ancient Egypt was adopted into the Western historical narrative and came to take on a significance that had up until that time been reserved for ancient Greek and Roman civilization.[48] The French revolutionaries justified the large-scale and systematic looting of Italy in 1796 by viewing themselves as the political successors of Rome, in the same way that ancient Romans saw themselves as the heirs of Greek civilization;[49] by the same token, the appropriation of ancient Egyptian history as European history further legitimated Western colonial rule over Egypt. But while ancient Egypt became patrimony of the West, modern Egypt remained a part of the Muslim world.[48] The writings of European archaeologists and tourists illustrate the impression that modern Egyptians were uncivilized, savage, and the antithesis of the splendor of ancient Egypt.[48]

Museums furnished by colonial looting have largely shaped the way a nation imagines its dominion, the nature of the human beings under its power, the geography of the land, and the legitimacy of its ancestors, working to suggest a process of political inheriting.[50] It is necessary to understand the paradoxical way in which the objects on display at museums are tangible reminders of the power held by those who gaze at them.[51] Eliot Colla describes the structure of the Egyptian sculpture room in the British Museum as an assemblage that "form[s] an abstract image of the globe with London at the center".[52] The British Museum, as Colla describes, presents a lesson of human development and progress: "the forward march of human civilization from its classical origins in Greece and Rome, through Renaissance Italy, to modern-day London".[52]

The restoration of monuments was often made in colonial states to make natives feel as if in their current state, they were no longer capable of greatness.[53] Furthermore, sometimes colonial rulers argued that the ancestors of the colonized people did not make the artifacts.[53] Some scholars also argue that European colonialists used monumental archaeology and tourism to appear as the guardian of the colonized, reinforcing unconscious and undetectable ownership.[53] Colonial rulers used peoples, religions, languages, artifacts, and monuments as source for reinforcing European nationalism, which was adopted and easily inherited from the colonial states.[53]

Nationalism and identity[]

As a direct reaction and resistance to colonial oppression, archaeology was also used for the purpose of legitimating the existence of an independent nation-state.[54] For example, Egyptian Nationalists utilized its ancient history to invent the political and expressive culture of "Pharaonism" as a response to Europe's "Egyptomania".[55]

Some argue that in colonized states, nationalist archaeology was used to resist colonialism and racism under the guise of evolution.[56] While it is true that both colonialist and nationalist discourse use the artifact to form mechanisms to sustain their contending political agendas, there is a danger in viewing them interchangeably since the latter was a reaction and form of resistance to the former. On the other hand, it is important to realize that in the process of emulating the mechanisms of colonial discourse, the nationalist discourse produced new forms of power. In the case of the Egyptian nationalist movement, the new form of power and meaning that surrounded the artifact furthered the Egyptian independence cause but continued to oppress the rural Egyptian population.[55]

Some scholars[who?] argue that archaeology can be a positive source of pride in cultural traditions, but can also be abused to justify cultural or racial superiority as the Nazis argued that Germanic people of Northern Europe was a distinct race and cradle of Western civilization that was superior to the Jewish race.[citation needed]. In other cases, archaeology allows rulers to justify the domination of neighboring peoples as Saddam Hussein used Mesopotamia's magnificent past to justify his invasion of Kuwait in 1990.[57]

Some scholars employ the idea that identity is fluid and constructed, especially national identity of modern nation-states, to argue that the post-colonial countries have no real claims to the artifacts plundered from their borders since their cultural connections to the artifacts are indirect and equivocal.[58] This argument asserts that artifacts should be viewed as universal cultural property and should not be divided among artificially created nation-states. Moreover, that encyclopedic museums are a testament to diversity, tolerance and the appreciation of many cultures.[59] Other scholars would argue that this reasoning is a continuation of colonialist discourse attempting to appropriate the ancient art of colonized states and incorporate it into the narrative of Western history.[citation needed]

Cultural survival and identity[]

In settler-colonial contexts, many Indigenous people that have experienced cultural domination by colonial powers have begun to request the repatriation of objects that are already within the same borders. Objects of Indigenous cultural heritage, such as ceremonial objects, artistic objects, etc., have ended up in the hands of publicly and privately held collections which were often given up under economic duress, taken during assimilationist programs or simply stolen.[60] The objects are often significant to the Indigenous ontologies possessing animacy and kinship ties. Objects such as particular instruments used in unique musical traditions, textiles used in spiritual practices or religious carvings have cult significance are connected to the revival of traditional practices. This means that the repatriation of these objects is connected to the cultural survival of Indigenous people historically oppressed by colonialism.[61]

Colonial narratives surrounding "discovery" of the new world have historically resulted in Indigenous people's claim to cultural heritage being rejected. Instead, private and public holders have worked towards displaying these objects in museums as a part of colonial national history. Museums often argue that if objects were to be repatriated they would be seldom seen and not properly taken care of.[62] International agreements such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention against Illicit Export under the Act to implement the Convention (the Cultural Property Implementation Act) often do not regard Indigenous repatriation claims. Instead, these conventions focus on returning national cultural heritage to states.[61]

Since the 1980s, decolonization efforts have resulted in more museums attempting to work with local Indigenous groups to secure a working relationship and the repatriation of their cultural heritage.[63] This has resulted in local and international legislation such as NAGPRA and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects which take Indigenous perspectives into consideration in the repatriation process. Notably, Article 12 of UNDRIP states:

Indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practise, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the right to the repatriation of their human remains. States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned.[64]

The process of repatriation has often been fraught with issues though, resulting in the loss or improper repatriation of cultural heritage. The debate between public interest, Indigenous claims and the wrongs of colonialism is the central tension around the repatriation of Indigenous cultural heritage.[60]

Controversies[]

The repatriation debate[]

The repatriation debate is a term referring to the dialogue between individuals, heritage institutions, and nations who have possession of cultural property and those who pursue its return to its country or community of origin.[65] It is suggested that many points within this debate center around the legal issues involved such as theft and the legality of acquisitions and exports, etc.[65] Two main theories seem to underpin the repatriation debate and cultural property law: cultural nationalism and cultural internationalism.[40] These theories emerged and developed following the creation of many international conventions, such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention, and act as the foundation of contradicting opinions regarding the transport of cultural objects.[40]

Cultural internationalism[]

Cultural internationalism has links to imperialism and decontextualization[40] and suggests that cultural property is not tethered to one nation and belongs to everybody. Calls for repatriation can therefore be dismissed since they are often requested when a nation declares ownership of an object,[65] which according to this theory is not exclusive.[40]

Some critics and even supporters of this theory seek to limit its scope. For example, proponent of cultural internationalism John Henry Merryman suggests that unauthorized archaeological discoveries should not be exported as information would be lost that would have remained intact if they stayed where they were discovered.[66]

It is further argued that this theory has close resemblance to the 'universal museums' theory.[40] Following a series of repatriation claims, leading museums issued a declaration detailing the importance of the universal museum.[67] The declaration argues that over time, objects acquired by the museums have become part of the heritage of that nation and that museums work to serve people from every country as "agents in the development of culture." It is on this justification that many repatriation requests are denied.[68] A notable example includes the Greek Parthenon marbles housed at the British Museum.[69]

Many of the issues surrounding the denial of repatriation requests originate from items taken during the era of imperialism (pre-1970 UNESCO Convention) as a wide range of opinions remains among museums.[68]

Cultural nationalism[]

Cultural nationalism has links to retentionism, protectionism, and particularism.[40] Following the 1970 UNESCO Convention and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention, cultural nationalism has become more popular than its opposing internationalist theory.[40]

Under the theory of cultural nationalism, nations seek to withhold cultural objects as their own heritage and actively seek the return of objects that are abroad (illegally or unethically).[40] Cultural nationalists suggest that keeping and returning objects to their country of origin tethers the object to its context and therefore overrides its economic value (abroad).[68]

Both cultural nationalism and internationalism could be used to justify the retention of cultural property depending on the point of view. Nations of origin seek retention to protect the wider context of the object as well as the object itself, whereas nations who acquire cultural property seek its retention because they wish to preserve the object if there is a chance it will be lost if transported.[66]

The repatriation debate often differs on case-by-case basis due to the specific nature of legal and historical issues surrounding each instance. Most of the arguments commonly used are discussed in the 2018 Report on the Restitution of African Cultural Heritage by Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy.[70] They can be summarized as follows:

Arguments against repatriation[]

- Artifacts are a part of a universal human history, and encyclopedic museums like the British Museum, Musée du Louvre and Metropolitan Museum of Art cultivate the dissemination of knowledge, tolerance, and broad cultural understanding. James Cuno suggests that repatriation claims are arguments against this encyclopedic promise.[71]

- Artifacts were frequently excavated or uncovered by looters, who brought to light a piece of artwork that would otherwise never have been found; foreign-led excavation teams have uncovered items that contribute to cultural knowledge and understanding.[72]

- Nationalist retentionist cultural property laws claiming ownership are founded on constructed boundaries of modern nations with weak connections to the culture, spirit, and ethnicity of the ancient peoples, who produced those works.[73][74]

- Cultural identities are dynamic, inter-related and overlapping, so no modern nation-state can claim cultural property as their own without promoting a sectarian view of culture.[71]

- Having artwork disseminated around the world encourages international scholarly and professional exchange.

- Encyclopedic museums are located in cosmopolitan cities such as London, Paris, Berlin, Rome or New York, and if the artworks were to be moved, they would be seen by far fewer people. If the Rosetta Stone were to be moved from The British Museum to The Cairo Museum, the number of people, who view it, would drop from about 5.5 million visitors to 2.5 million visitors a year.[75]

Arguments for repatriation[]

- Encyclopedic museums such as the British Museum, Musée du Louvre and Metropolitan Museum of Art were established as repositories for looted art during imperial and colonial rule, and thus are located in metropolitan cities out of view and reach of the cultures from which they were appropriated.

- Precedence of repatriated art has already been set in many cases, but the artworks that museums currently refuse to repatriate are often their most valuable and famous artworks.

- Foreign-led excavations have justified colonial rule and vice versa; in the pursuit of obtaining knowledge about the artifacts, there was a need to establish control over the artifacts and the countries, where they were located.[70]

- The argument that art is a part of universal human history is a derivative of colonial discourse that appropriated the art of other cultures into the Western historical narrative.

- The encyclopedic museums that house much of the world's artworks and artifacts are located in Western cities and privilege European scholars, professionals and people, while at the same time excluding people in the countries of origin.[76]

- The argument that artwork will not be protected outside of the Western world is hypocritical, as much of the artwork transported out of colonized countries was crudely removed, often damaged and sometimes lost in transportation. The Elgin marbles for example, were damaged during the cleaning and "preservation" process. As another example, the Napried, one of the ships commissioned by di Cesnola to transport approximately 35,000 pieces of antiquities that he had collected from Cyprus, was lost at sea carrying about 5,000 pieces in its cargo.[77]

- Art is best appreciated and understood in its original historical and cultural context.[68] Following the return of cultural property, the intangible meaning and aspects of that culture also return, this may promote the return of intangible traditions and educate future generations within indigenous communities.[78]

- Art taken out of the country as a spoil of war, by looting, and as a deliberate act of colonialism, is unethical, even if this is not explicitly reflected in legislation. The possession of artwork taken under these conditions is a form of continued colonialism.[76]

- The lack of existing legal recourse for claiming the return of illicitly appropriated cultural property is a result of colonization. Michael Dodson notes that colonization has taken "our distinct identities and cultures."[79]

- Art is a symbol of cultural heritage and identity, and the unlawful appropriation of artworks is an affront to a nation's pride. Moira Simpson suggests that repatriation helps indigenous communities renew traditional practices that were previously lost, this is the best method of cultural preservation.[78][80]

- Susan Douglas and Melanie Hayes note that national collections often have fixed practices, like collecting and owning cultural objects, which can be influenced by a colonial structure.[81]

- Following the repatriation of cultural objects and ancestral remains, indigenous communities may begin to heal by connecting the past and the present.[82][83]

The 'New Stream' theory (Indeterminacy)[]

Pauno Soirila argues that the majority of the repatriation debate is stuck in an "argumentative loop" with cultural nationalism and cultural internationalism on opposing sides, as evidenced by the unresolved case of the Parthenon marbles. Introducing external factors is the only way to break it.[84] Introducing claims centered around communities' human rights has led to increased indigenous defense and productive collaborations with museums and cultural institutions.[85][86] While human rights factors alone cannot resolve the debate, it is a necessary step towards a sustainable cultural property policy.[84]

International examples[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2019) |

Australia[]

Australian Aboriginal cultural artefacts as well as people have been the objects of study in museums; many were taken in the decades either side of the turn of the 20th century. There has been greater success with returning human remains than cultural objects in recent years, as the question of repatriating objects is less straightforward than bringing home ancestors.[87] More than 100,000 Indigenous Australian artefacts are held in over 220 institutions across the world, of which at least 32,000 are in British institutions, including the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.[88][89]

Australia has no laws directly governing repatriation, but there is a government programme relating to the return of Aboriginal remains and artefacts, the International Repatriation Program (IRP), administered by the Department of Communications and the Arts. This programme "supports the repatriation of ancestral remains and secret sacred objects to their communities of origin to help promote healing and reconciliation" and assists community representatives work towards repatriation of remains in various ways.[90][91][92]

Gweagal man Rodney Kelly and others have been working to achieve the repatriation of the Gweagal Shield and Spears from the British Museum[93] and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, respectively.[94] Jason Gibson notes how there is a lack of Australian aboriginal authority surrounding collections and so protocols have instead been made by non-indigenous professionals.[95]

The matter of repatriation of cultural artefacts such as the Gweagal shield was raised in federal parliament on 9 December 2019, receiving cross-bench support. With the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook's landing looming in April 2020, two Labor MPs called on the government to “establish a process for the return of relevant cultural and historical artefacts to the original custodians and owners".[96]

Returns[]

The Return of Cultural Heritage program run by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) began in 2019, the year before the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook's first voyage to Australia. The program has worked towards the return of a number of the approximately 105,000 identified objects held by foreign institutions.[89]

In late October 2019 the first collection of many sacred artefacts held in US museums were returned by Illinois State Museum.[97] 42 Aranda (Arrernte) and Bardi Jawi objects removed from central Australia in 1920 were the first group. The next phase of the project would repatriate 40 culturally significant objects from the Manchester Museum in the UK, which would be returned to the Aranda, Ganggalidda, Garawa, Nyamal and Yawuru peoples. AIATSIS project leader Christopher Simpson said they hoped that the project could evolve into an ongoing program for the Federal Government.[97] In November 2019, the objects were returned from Manchester Museum, which included sacred artefacts collected 125 years earlier from the Nyamal people of the Pilbara region of Western Australia.[98][88] Manchester Museum returned 19 sacred objects to the Arrernte people during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was finally celebrated in May 2021. Another 17 items held at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at the University of Virginia also due to be returned to a number of Aboriginal nations.[89]

While communities note the positive impact of returning bones of ancestors back to their country of origin, some also declare it has provoked tensions within communities e.g. the requirement of legal title of land to bury them and determining who has the authority to perform traditional ceremonies.[99]

Rapa Nui[]

On Rapa Nui, of the dozens of moai figures which have been removed from the landscape of Rapa Nui since the first one was removed in 1868 for installation in the British Museum, only one has been repatriated to date. This was a moai taken from the island in 1929 and repatriated in 2006.[100]

Canada[]

The Haisla totem Pole of Kitimat, British Columbia was originally prepared for chief G'psgoalux in 1872. This aboriginal artifact was donated to a Swedish museum in 1929. According to the donor, he had purchased the pole from the Haisla people while he lived on the Canadian west coast and served as Swedish consul. After being approached by the Haisla people, the Swedish government decided in 1994 to return the pole, as the exact circumstances around the acquisition were unclear. The pole was returned to Kitimat in 2006 after a building had been constructed in order to preserve the pole.

During the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics, the Glenbow museum received harsh criticism for their display “The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada's First People”. Initially, the criticism was due to the Olympic's association with Shell Oil who were exploring oil and gas in territories contested by Lubicon Cree. Later Mowhawk would sue the Glenbow museum for the repatriation of a False Face Mask they had displayed arguing that they considered it to be of religious ceremonial significance.[63] The museum did not listen to the Indigenous claim and brought the issue to court. Glenbow won and was able to display the mask but the controversy highlighted the ways in which museums have often dismissed the living cultures they should be working with. This led to a movement to improve the involvement of Indigenous people in their representation in museums.[101] The Canadian Museums Association and Assembly of First Nations led a Task Force on Museums and First Peoples. The task force would publish the report Turning the Page in 1992 that put forward a series of findings which would help improve Indigenous involvement in the museum process. Among these was a focus on creating a partnership between Indigenous people and the museum curators which involves allowing Indigenous people into the planning, research and implementation of collections. Museums were urged to also improve ongoing access to the collections and training for both curators and Indigenous people who want to be involved in the process. Finally, an emphasis was placed on repatriation claims of human remains, locally held objects (using practice customary to the Indigenous people in question) and foreign held objects.[102]

In 1998, over 80 Ojibwe ceremonial artifacts were repatriated to a cultural revitalization group by The University of Winnipeg. The controversy came as this group was not connected to the source community of the objects. Some of the objects were later returned but many are still missing.[103]

Egypt[]

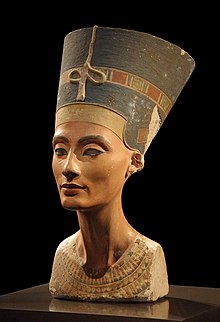

The Egyptian government is seeking the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum and the Nefertiti bust from the Neues Museum in Berlin.[citation needed]

Greece[]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

Greece is seeking repatriation of the Elgin Marbles from the British Museum,[104] taken from the Parthenon by the Earl of Elgin. Since 1816, the British Museum has held the Parthenon Marbles after purchasing them from the Earl of Elgin. The acquisition of the marbles was met with controversy in Britain, with some supporting the decision while others condemning it as vandalism. Despite requests for repatriation from the Greek government, the museum strongly defends its right to own and display the marbles.[original research?]

India[]

The British government has rejected demands from the Indian government to repatriate artifacts such as the "Kohinoor Diamond" and "Sultanganj Buddha" which were taken from the Indian subcontinent during the period of British colonial rule, citing citing a law (British Museum Act 1963) that prevents it from giving back the items. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is planning to join a campaign with the support of UNESCO and other countries to repatriate the artifacts.[when?][citation needed]

Ireland[]

Ireland lies in an unusual place with regard to the repatriation of cultural artefacts; the entire island was under British rule until 1922, when part of it became the independent Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland). During the centuries of British rule, many Irish historical artefacts made their way into British collections and museums.[105] At the same time, many Anglo-Irish (and some Catholic Irish) people went abroad as part of the armies and administrators of the British Empire, and objects acquired in the Empire are now in several Irish museums and collections.

Foreign objects in Ireland[]

For example, the National Museum of Ireland holds over 15,000 objects in its ethnographic collections; in 2021, head of collections Audrey Whitty announced that the museum group would investigate its collections, with a view to repatriation of those viewed as "plunder."[106] In 2013, Fintan O'Toole noted that much of the material in the NMI's ethnographic collection "lies in the grey area between trade and coercive acquisition: an expansive terrain in imperial relations," but that other objects were unambiguously loot, taken in punitive expeditions in Africa, Asia and Oceania.[107] In April 2021, the National Museum announced that 21 Benin bronzes would be returned to Africa.[108] Similar questions surround the Hunt Museum (Limerick) and the Ulster Museum (in Northern Ireland, still part of the United Kingdom).[109]

In 2017, Senator Fintan Warfield called on Irish museums to return looted objects, saying that "such material should only be returned following a national conversation, as well as the public display and independent survey of such collections, and provided that their final destination is safe and secure [...] we should not forget that such collections are and always will be the heritage of indigenous people around the world; in locations such as Burma, China, and Egypt." The Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht objected based on cost grounds, and noted that institutions such as National Museum and National Library enjoy curatorial independence.[110]

Irish artefacts abroad[]

Dr Laura McAtackney of Aarhus University has noted that "Amongst discussions on repatriation from colonial museums, Irish objects are almost absent, when of course most were deposited in the British Museum (amongst other museums) pre-independence."[111]

The skeleton of the "Irish Giant" Charles Byrne (1761–1783) is on public display in the Hunterian Museum, despite it being Byrne's express wish to be buried at sea. Author Hilary Mantel called in 2020 for his remains to be buried in Ireland.[112]

Augustus Pitt Rivers removed three 5th-century ogham stones from Roovesmoor Rath, County Cork; they now stand in the British Museum.[113] The British Museum also holds 200 Irish-language manuscripts, many bequeathed by landowners but some also undoubtedly stolen, such as the Book of Lismore, seized by Lewis Boyle, 1st Viscount Boyle of Kinalmeaky in the Irish Confederate Wars.[114] Other notable Irish artefacts in the British Museum include the Bell Shrine of St. Cuileáin, swords, the Kells Crozier, torcs, armlets, seals, religious plaques, and rings.[115] These were mostly acquired in the colonial period, many under unclear circumstances.[116]

Within Ireland[]

Victorian anthropologists from Trinity College Dublin (then a bastion of British colonialism and the Protestant Ascendancy) removed skulls from monastic sites in the West of Ireland (then seen as a wild and primitive Gaelic place). The repatriation of these remains has also been requested.[117][118]

Israel[]

Even though Turkey has launched an aggressive campaign to repatriate Ottoman-era artifacts it claims were looted by imperial powers, it has refused to return the Siloam inscription (and other artifacts unearthed in Palestine and transferred to Turkey) to Israel.[119] This inconsistent position has been noted by Hershel Shanks, founder of the Biblical Archaeology Review, among others.[120]

Italy[]

In February 2006, the Metropolitan Museum of Art negotiated the repatriation of the Euphronios krater to Italy, from where it was thought to have been looted in the early 1970s.

Morocco[]

In 1612, the personal library of Sultan Zaydan An-Nasser of Morocco was trusted to French consul for transportation. After Castellane waited for six days not receiving his pay, he sailed away. But four Spanish ships from Admiral Luis Fajardo's fleet captured the ship and took it to Lisbon (then part of the Spanish Empire). In 1614, the Zaydani Library was transmitted to El Escorial. Moroccan diplomats have since asked for the manuscripts to be returned. Some other Arabic manuscripts have been delivered by Spain, but not the Zaydani collection. In 2013, the Spanish Cultural Heritage Institute presented microfilm copies of the manuscripts to Moroccan authorities.[121][122]

South Korea[]

In November 2010, Japan agreed to return some 1,000 cultural objects to South Korea that were plundered during its colonial occupation from 1910-45. The collection includes a collection of royal books called Uigwe from the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).[123]

United Kingdom[]

In July 1996, the British Government agreed to return the Stone of Scone to Scotland, which had been taken to London in 1296 and placed in the newly-made Coronation Chair, following growing dissatisfaction among Scots at the prevailing constitutional settlement.[124]

In 1997, investigative journalism uncovered Sotheby's trading in illicit antiquities.[125] From the late 1980s through to the early 1990s, Sotheby's antiquities department in London was managed by Brendan Lynch and Oliver Forge, who traded with Vaman Ghiya in Rajasthan, India. Many of the pieces they bought turned out to be stolen from temples and other sites, and as a result of this exposé, Sotheby's commissioned their own report into illegal antiquities, and made assurances that only legal items with published provenance would be traded in the future.[126][127]

The British Museum has been claimed to be the largest receiver of "stolen goods" in the world, but has consistently refused to return objects citing the British Museum Act 1963 as preventing restitution,[128] with a few exceptions. Prominent examples of restitution requests for artifacts in the British Museum include the Benin Bronzes and the Parthenon Marbles.[128] These have become points of controversy for the British Museum, with the Nigerian and Greek governments demanding for the repatriation of the artifacts since the 1960s.[citation needed][104]

United States[]

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, provides a process for museums and federal agencies to return certain cultural items such as human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, etc. to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organisations.[129][87] However, the legislation has its limitations and has been successfully contested both domestically and extraterritorially.[130]

The Iraqi Jewish Archive is a collection of 2,700 books and tens of thousands of historical documents from Iraq's Jewish community discovered by the United States Army in the basement of Saddam Hussein's intelligence headquarters during the US invasion of Iraq in 2003.[131] These materials were abandoned during Operation Ezra and Nehemiah in the 1950s, when almost all Iraqi Jews made aliyah to Israel on the condition (imposed by the Iraqi government) that they leave their property behind. The archive has been in temporary US custody since 2003, and is scheduled to be transferred permanently to Iraq in 2018. This plan is controversial: some[who?] Middle-East scholars and Jewish organizations have opined that because the materials were abandoned under duress, and because almost no Jews live in Iraq today, the archive should instead be housed in Israel or the United States.[citation needed]

See also[]

- Report on the restitution of African cultural heritage

- Byzantine Fresco Chapel, Houston

- Decolonization of museums

- Iraqi Jewish Archive

- Repatriation and reburial of human remains

- Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

Notes and references[]

- ^ According to the Sumerian poem titled , Naram-Sin was responsible for the collapse of the Akkadian Empire as he looted and destroyed the and incited the wrath of the gods as a result, see Miles, p. 16

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miles, p. 20

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miles, p. 13

- ^ Miles, p. 65

- ^ Isager, Jacob, Pliny on Art and Society: The Elder Pliny's Chapters On The History Of Art, p. 173, 2013, Routledge, ISBN 1-135-08580-3, 978-1-135-08580-3, Google Books

- ^ Gilks, David (2013-02-01). "Attitudes to the Displacement of Cultural Property in the Wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon". The Historical Journal. 56 (1): 113–143. doi:10.1017/S0018246X12000453. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 146537855.

- ^ "Napoleon's appropriation of Italian cultural treasures". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ^ See film, Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War by L.H. Nicholas, New York, 1994

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Unplundering Art". Economist. 1997.

- ^ Barry Meier and James Glanz (26 July 2006). "Looted treasure returning to Iraq national museum". New York Times. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greenfield, p. 263

- ^ Jump up to: a b Poole, Robert M. (February 2008). "Looting Iraq". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greenfield, p. 268

- ^ Greenfield, p. 267

- ^ Well known examples include Lucius Mummius' sack of Corinth or Marcus Claudius Marcellus' plunder of Syracuse, See Miles, p. 320

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miles, p. 320

- ^ See Miles, p. 320

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miles, p. 321

- ^ The Laocoön was the fabled Trojan priest who warned the Trojans not to accept the Wooden Horse that the Greeks offered to Athena. A god hostile to Troy sent sea serpents to kill him and his sons, which led to the fall of Troy and heralded the eventual founding of Rome, see Miles, p. 321

- ^ Ironically one of the names included Vivant Denon, the future Director of the Louvre and future facilitator of Napoleon's despoliation of artifacts from Egypt (see Miles, p. 326)

- ^ Miles, p. 328

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Miles, p. 329

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hardy, Samuel Andrew (2021). "Conflict antiquities' rescue or ransom: The cost of buying back stolen cultural property in contexts of political violence". International Journal of Cultural Property. 28: 5–26. doi:10.1017/S0940739121000084.

- ^ "Brodie, N. (2005), 'The circumstances and consequences of the British Library's 1994 acquisition of some Kharosthi manuscript fragments', Culture Without Context (17), 5–12. « Trafficking Culture". Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ^ Miles, p.4

- ^ Miles, p.5

- ^ Miles, p. 5

- ^ Miles, p. 330

- ^ Miles, p. 331

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miles, p. 334

- ^ Miles, p. 341

- ^ Miles, p. 332

- ^ Miles, p. 144

- ^ Miles, p. 350

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miles, p. 352

- ^ Miles, p. 271

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris, Faye (2015-03-15). "Understanding human remains repatriation: practice procedures at the British Museum and the Natural History Museum". Museum Management and Curatorship. 30 (2): 138–153. doi:10.1080/09647775.2015.1022904. ISSN 0964-7775. S2CID 144304347.

- ^ Cassman, Vicki; Odegaard, Nancy; Powell, Joesph (2007). "Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions". AltaMira Press: 21–27.

- ^ The British Museum Policy on Human Remains, https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/00%2001%20BM%20Policy%20Human%20Remains%206%20Oct%202006.pdf

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Stamatoudi, Irini A. (2011-01-01). Cultural Property Law and Restitution: A Commentary to International Conventions and European Union Law. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85793-030-9.

- ^ Lewis, Geoffrey (1983). "ATTITUDES TOWARDS CULTURAL PROPERTY: Some thoughts in the context of the return of cultural property to its country of origin". Newsletter (Museum Ethnographers Group) (14): 16–33. ISSN 0260-0366. JSTOR 40838690.

- ^ Greenfield, p. 270

- ^ Jump up to: a b Riviere, Francoise (2009). "Editorial". Museum International. 1-2. 61 (1–2): 4–5. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.2009.01686.x. S2CID 218510782.

- ^ Bouchenaki, Mounir (2009). "Return and restitution of cultural property in the wake of the 1970 Convention". Museum International. 1-2. 61 (1–2): 139–144. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.2009.01676.x. S2CID 143352763.

- ^ "FORTHCOMING EVENTS - Index". www.unidroit.org. Archived from the original on March 26, 2010.

- ^ Silberman, pp. 249-50

- ^ Said 86

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Colla 103

- ^ Miles 320

- ^ Anderson 164

- ^ Colla 4

- ^ Jump up to: a b Colla 5

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Anderson 181

- ^ Diaz-Andreu, p. 54

- ^ Jump up to: a b Colla 12

- ^ Kohl, Fawcett, pp. 3-11

- ^ Kohl, Fawcett, p. 5

- ^ Cuno, pp. xx-xxxvi

- ^ Cuno, pp. xxxv

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tuensmeyer, Vanessa M. (2014), "Repatriation and Multilevel Heritage Legislation in Canada and Australia: A Comparative Analysis of the Challenges in Repatriating Religious Artefacts to Indigenous Communities", in Vadi, Valentina; Schneider, Hildegard E. G. S. (eds.), Art, Cultural Heritage and the Market, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 183–206, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45094-5_8, ISBN 978-3-642-45093-8

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yupsanis, Athanasios (2012). "Cultural Property Aspects in International Law: The Case of the (Still) Inadequate Safeguarding of Indigenous Peoples' (Tangible) Cultural Heritage". Netherlands International Law Review. 58 (3): 335–361. doi:10.1017/S0165070X11300022. ISSN 1741-6191. S2CID 143559885.

- ^ Nafziger, James A. R.; Nicgorski, Ann (2011). "Conference on Cultural Heritage Issues: The Legacy of Conquest, Colonization and Commerce, Willamette University, Salem, Oregon October 12–14, 2006". International Journal of Cultural Property. 14 (4). doi:10.1017/s0940739107070300. ISSN 0940-7391. S2CID 163091191.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Conaty, Gerald, ed. (2015-03-23). We Are Coming Home: Repatriation and the Restoration of Blackfoot Cultural Confidence. doi:10.15215/aupress/9781771990172.01. ISBN 9781771990189.

- ^ "United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Shapiro, Daniel (1998–1999). "Repatriation: A Modest Proposal". New York University Journal of International Law and Politics. 31: 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Merryman, John Henry (1986). "Two Ways of Thinking About Cultural Property". American Journal of International Law. 80 (4): 831–53. doi:10.2307/2202065. JSTOR 2202065.

- ^ "Declaration of The Importance and Value of Universal Museums | PDF | Museum | Sculpture". Scribd. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hallman, Robert (2005). "Museums and Cultural Property: A Retreat from the Internationalist Approach". International Journal of Cultural Property. 12 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1017/S0940739105050095. S2CID 145709758.

- ^ Knox, Christine K (2006). "They've Lost Their Marbles: 2002 Universal Museums' Declaration, The Elgin Marbles and the Future of the Repatriation Movement". Suffolk Transnational Law Review. 29: 315–336.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Felwine Sarr, Bénédicte Savoy: "Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle". Paris 2018; "The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics" (Download French original and English version, pdf, http://restitutionreport2018.com/

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cuno, James (2014). "Culture War: The Case Against Repatriating Museum Artifacts". Foreign Affairs. 93 (6): 119–129. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 24483927.

- ^ Donnan, Christopher B.; Sudduth, W. M.; Dietz, Park Elliott; Adams, Richard E. W. (1991). "Archeology and Looting: Preserving the Record". Science. 251 (4993): 498–499. doi:10.1126/science.251.4993.498. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 2875056. PMID 17840843. S2CID 5270999.

- ^ Cuno, James (2008). Who Owns Antiquity? The Battle Over Our Ancient Heritage. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Cuno, James (2 November 2010). "Who's Right? Repatriation of Cultural Property". Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Egypt demands return of the Rosetta Stone The Telegraph. By Charlotte Edwardes and Catherine Milner, 20 Jul 2003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wang, Shuchen (2020-12-02). "Museum coloniality: displaying Asian art in the whitened context". International Journal of Cultural Policy. 0: 1–18. doi:10.1080/10286632.2020.1842382. ISSN 1028-6632. S2CID 229412013.

- ^ "Napried Exploration". napried.com. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Simpson, Moira (2009-05-01). "Museums and restorative justice: heritage, repatriation and cultural education". Museum International. 61 (1–2): 121–129. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.2009.01669.x. ISSN 1350-0775. S2CID 31432460.

- ^ Michael Dodson, 'Cultural Rights and Educational Responsibilities', The Frank Archibald Memorial Lecture, University of New England, 5 September 1994

- ^ Atkinson, Henry (2010). "The Meanings and Values of Repatriation". The Long Way Home. Berghahn Books. pp. 15–19. ISBN 9781845459581. JSTOR j.ctt9qcnn7.5.

- ^ Douglas, Susan; Hayes, Melanie (2019). "Giving Diligence its Due: Accessing Digital Images in Indigenous Repatriation Efforts". Heritage. 2 (2): 1260–1273. doi:10.3390/heritage2020081.

- ^ Aranui, Amber Kiri (2020-03-23). "Restitution or a Loss to Science? Understanding the Importance of Māori Ancestral Remains". Museum and Society. 18 (1): 19–29. doi:10.29311/mas.v18i1.3245. ISSN 1479-8360.

- ^ Winkelmann, Andreas (2020-03-23). "Repatriations of human remains from Germany – 1911 to 2019". Museum and Society. 18 (1): 40–51. doi:10.29311/mas.v18i1.3232. ISSN 1479-8360.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Soirila, Pauno (2021-04-01). "Indeterminacy in the cultural property restitution debate". International Journal of Cultural Policy. 0: 1–16. doi:10.1080/10286632.2021.1908275. ISSN 1028-6632.

- ^ Esterling, Shea Elizabeth (2020-10-28). "Legitimacy, Participation and International Law-Making: 'Fixing' the Restitution of Cultural Property to Indigenous Peoples". Changing Actors in International Law: 158–184. doi:10.1163/9789004424159_008. ISBN 9789004424159.

- ^ Jenkins, Tiffany (2010-12-14). Contesting Human Remains in Museum Collections: The Crisis of Cultural Authority. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-89786-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cook, Myles Russell; Russell, Lynette (1 December 2016). "Museums are returning indigenous human remains but progress on repatriating objects is slow". The Conversation. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halliday, Josh (21 November 2019). "Manchester museum returns stolen sacred artefacts to Indigenous Australians". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Abram, Mitchell (20 May 2021). "Sacred Arrernte objects returned to Alice Springs from English museum". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Indigenous repatriation". Australian Government. Department of Communications and the Arts. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Aboriginal remains repatriation". Creative Spirits. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Note: There was previously also a domestic Return of Indigenous Cultural Property (RICP) program run by the former Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

- ^ Keenan, Sarah (18 May 2018). "How the British Museum changed its story about the Gweagal Shield". Australian Critical Race and Whiteness Studies Association. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Once were warriors". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 November 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Gibson, Jason (2019-05-04). "'You're my kwertengerl': transforming models of care for central Australian aboriginal museum collections". Museum Management and Curatorship. 34 (3): 240–256. doi:10.1080/09647775.2018.1549506. ISSN 0964-7775. S2CID 149957344.

- ^ FitzSimons, Peter (11 December 2019). "Morrison needs to get behind push to bring precious Aussie artefacts home". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beavan, Katrina. "Sacred Indigenous artefacts handed back to Aranda and Bardi Jawi elders after 100 years in US". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Standen, Susan; Parish, Rebecca; Moodie, Claire. "Indigenous artefacts returned after decades in overseas museums". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Turnbull, Paul (2020-03-23). "International Repatriations of Indigenous Human Remains and Its Complexities: the Australian Experience". Museum and Society. 18 (1): 6–18. doi:10.29311/mas.v18i1.3246. ISSN 1479-8360.

- ^ Aires, Buenos (April 18, 2006). "Easter Island statue heads home". The Age.

- ^ Harrison, Julia D.; Trigger, Bruce (December 1988). "'The Spirit Sings' and the Future of Anthropology". Anthropology Today. 4 (6): 6. doi:10.2307/3032945. ISSN 0268-540X. JSTOR 3032945.

- ^ "Task Force Report on Reconciliation" (PDF).

- ^ Matthews, Maureen Anne (2016). Naamiwan's drum: the story of a contested repatriation of Anishinaabe artefacts. Toronto. ISBN 978-1-4426-2243-2. OCLC 965828368.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Helena Smith (20 June 2020). "'Product of theft': Greece urges UK to return Parthenon marbles". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Cavan gems on display virtually". Anglo Celt.

- ^ Coyle, Colin. "National Museum of Ireland looks to hand back colonial plunder" – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- ^ O'Toole, Fintan. "Culture Shock: Never mind the Nazis. What about Ireland's own stolen treasures?". The Irish Times.

- ^ Shortall, Eithne. "National Museum of Ireland forges plan to return looted Benin bronzes" – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- ^ Warfield, » Fintan. "Stolen goods will always be Stolen goods". www.anphoblacht.com.

- ^ Hosford, Paul. "Ireland should 'give back its looted and stolen treasures'". TheJournal.ie.

- ^ @LMcAtackney (2 October 2020). "Amongst discussions on repatriation..." (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Murphy, Darragh Peter (October 15, 2020). "Hilary Mantel calls for skeleton of Irish 'giant' to be repatriated". the Guardian.

- ^ "Stolen moments in British Museum". Irish Examiner. November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Cultural Objects: 12 Feb 2021: Seanad debates (KildareStreet.com)". www.kildarestreet.com.

- ^ "Kells's request for loan of its treasures strikes snags". The Irish Times.

- ^ "Collections Online | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org.

- ^ Walsh, Ciarán (April 11, 2021). "The case of the missing skulls from Inishbofin" – via www.rte.ie. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Webinar on Human Remains in Museums and other Collections, 9pm, Sept 2, 2020 | Maynooth University". www.maynoothuniversity.ie.

- ^ Zion, Ilan Ben. "Despite detente, ancient Hebrew text 'proving' Jewish ties to Jerusalem set to stay in Istanbul". www.timesofisrael.com.

- ^ "Please Return the Siloam Inscription to Jerusalem". The BAS Library. August 24, 2015.

- ^ *For details of the incident see: Chantal de la Véronne, Histoire sommaire des Sa'diens au Maroc, 1997, p. 78.

- Catalogue: Dérenbourg, Hartwig, Les manuscrits arabes de l'Escurial / décrits par Hartwig Dérenbourg. - Paris : Leroux [etc.], 1884-1941. - 3 volumes.

- ^ Journal of Early Modern History 18 (2014) 535-538 "Traveling Libraries: The Arabic Manuscripts of Muley Zidan and the Escorial Library" by Daniel Hershenzon of University of Connecticut ([1])

- ^ Tong, Xiong (8 November 2010). "S Korea to retrieve stolen cultural property from Japan: media". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ "The return north of Jacob's pillow may prove cold comfort to Mr Major, argues Malcolm Dickson Tory moment of destiny". The Glasgow Herald. 4 July 1996. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "TV Sting reveals illegal art deal" (12 February 1997). The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Smuggled art clampdown by Sotheby's" (17 December 1997). The Times.

- ^ Boland, Michaela (2 October 2014). "Doubts shroud idol deals". The Australian. [Alternative title? Doubts emerge over Indian idols at Art Gallery of South Australia]. p. 11. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Duthie, Emily (2011). "The British Museum: An Imperial Museum in a Post-Imperial World". Public History Review. 18: 17. doi:10.5130/phrj.v18i0.1523.

- ^ "FAQ". NAGPRA. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Kevin P. Ray, NAGPRA and Its Limitations: Repatriation of Indigenous Cultural Heritage, 15 J.MARSHALL REV.INTELL.PROP.L.472(2016).PDF

- ^ Sandi Fox (29 Apr 2014). "Who owns the Jewish treasures that were hidden in Saddam Hussein's basement?". PBS Newshour.

Cited works[]

- Anderson, Benedict (2006). Imagined Communities. Verso. pp. 163–186. ISBN 9781844670864.

- Colla, Elliot (2007). Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity. Duke University Press.

- Cuno, James (2008). Who Owns Antiquity? The Battle Over Our Ancient Heritage. Princeton University Press.

- Diaz-Andreu, M. (1993). "Theory and Theology: Spanish Archaeology under the Franco Regime". Antiquity. 67: 74–82. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00045075.

- Kohl, Philip; Fawcett, Clare (1995). Nationalism, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–18.

- Miles, Margaret M. (2008). Art as Plunder: The Ancient Origins of Debate About Cultural Property. Cambridge University Press.

- Moss, Paul (16 January 2009). "Masada legend galvanises Israel". BBC. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- Said, Edward (1994). Orientalism. Vintage Books.

- Silberman, N.A. (1982). Digging for God and Country. Knoph, New York.

Further reading[]

Books[]

- Jenkins, Tiffany (2016). Keeping Their Marbles: how the treasures of the past ended up in museums – and why they should stay there. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199657599.

- Merryman, John Henry (2006). Imperialism, Arts and Restitution. Cambridge University Press.

- Reid, Donald Malcolm (2002). Whose Pharaohs?: archaeology, museums, and Egyptian national identity from Napoleon to World War I. University of California Press.

- Waxman, Sharon (2008). Loot: The Battle Over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World. Times Books. ISBN 9780805086539.

Online[]

- Sullivan, Ann Marie (2016). "Cultural Heritage & New Media: A Future for the Past" (PDF). John Marshall Review of Intellectual Property Law. 15 (3): 604.

Art repatriation

- The Return Address: Where Does Heritage Belong? (2020, dir. Issabella Orlando) Documentary Film

- Sources of Information on Antiquities Theft

- Discussion of ethics

- 2006 article from the University of Wisconsin

Looted art

- San Francisco Chronicle, 2003 article on repatriation of looted art

- Attempts to locate looted art in British regional museums

- WWII and the Looted Art Problem

- Quedlinburg Art Affair

- Dispute: "Cuneiform Tablets in the News"

Cultural repatriation

- Cultural heritage

- Art and cultural repatriation