Robert Sapolsky

Robert Sapolsky | |

|---|---|

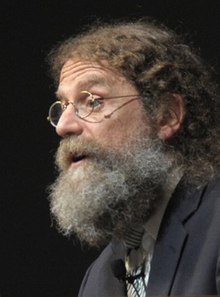

Sapolsky in 2009 | |

| Born | April 6, 1957 |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Harvard University (B.A.) Rockefeller University (Ph.D.) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neurobiology, physiology,[1] biological anthropology |

| Institutions | Stanford University |

| Thesis | The Neuroendocrinology of Stress and Aging (1984) |

| Doctoral advisor | Bruce McEwen |

| Other academic advisors | Melvin Konner[2] |

Robert Morris Sapolsky (born April 6, 1957) is an American neuroendocrinology researcher and author. He is currently a professor of biology, and professor of neurology and neurological sciences and, by courtesy, neurosurgery, at Stanford University. In addition, he is a research associate at the National Museums of Kenya.[3]

Early life and education[]

Sapolsky was born in Brooklyn, New York, to immigrants from the Soviet Union. His father, Thomas Sapolsky, was an architect who renovated the restaurants Lüchow's and Lundy's.[4] Robert was raised an Orthodox Jew and spent his time reading about and imagining living with silverback gorillas. By age 12, he was writing fan letters to primatologists. He attended John Dewey High School and, by that time, he was reading textbooks on the subject and teaching himself Swahili.[5]

Sapolsky describes himself as an atheist.[6][7] He stated in his acceptance speech for the Emperor Has No Clothes Award, "I was raised in an Orthodox [Jewish] household, and I was raised devoutly religious up until around age 13 or so. In my adolescent years, one of the defining actions in my life was breaking away from all religious belief whatsoever."[8]

In 1978, Sapolsky received his B.A. in biological anthropology summa cum laude from Harvard University.[9][10] He then went to Kenya to study the social behaviors of baboons in the wild. When the Uganda–Tanzania War broke out in the neighboring countries, Sapolsky decided to travel into Uganda to witness the war up close, later commenting that "I was twenty-one and wanted adventure. [...] I was behaving like a late-adolescent male primate."[11] He went to Uganda's capital Kampala, and from there to the border with Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and then back to Kampala, witnessing some fighting,[12] including the Ugandan capital's conquest by the Tanzanian army and its Ugandan rebel allies on 10–11 April 1979.[13] Sapolsky then returned to New York and studied at Rockefeller University, where he received his Ph.D. in neuroendocrinology[9][10] working in the lab of endocrinologist Bruce McEwen.

After the initial year-and-a-half field study in Africa, he would return every summer for another twenty-five years to observe the same group of baboons, from the late 70s to the early 90s. He spent 8 to 10 hours a day for approximately four months each year recording the behaviors of these primates.[14]

Career[]

Sapolsky is currently the John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Professor at Stanford University, holding joint appointments in several departments, including Biological Sciences, Neurology & Neurological Sciences, and Neurosurgery.[15]

As a neuroendocrinologist, he has focused his research on issues of stress and neuronal degeneration, as well as on the possibilities of gene therapy strategies for protecting susceptible neurons from disease.[16] Currently, he is working on gene transfer techniques to strengthen neurons against the disabling effects of glucocorticoids.[citation needed] Each year, Sapolsky spends time in Kenya studying a population of wild baboons in order to identify the sources of stress in their environment, and the relationship between personality and patterns of stress-related disease in these animals.[17] More specifically, Sapolsky studies the cortisol levels between the alpha male and female and the subordinates to determine stress level. An early but still relevant example of his studies of olive baboons is to be found in his 1990 Scientific American article, "Stress in the Wild".[18] He has also written about neurological impairment and the insanity defense within the American legal system.[19][20]

Sapolsky's work has been featured widely in the press, most notably in the National Geographic documentary Stress: Portrait of a Killer,[21][22] articles in The New York Times,[23][24] Wired magazine,[25] the Stanford magazine,[26] and The Tehran Times.[27] His speaking style (e.g., on Radiolab,[28] The Joe Rogan Experience,[29] and his Stanford human behavioural biology lectures[30]) has garnered attention.[31] Sapolsky's specialization in primatology and neuroscience has made him prominent in the public discussion of mental health—and, more broadly, human relationships—from an evolutionary context.[32][33]

Sapolsky has received numerous honors and awards for his work, including the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship Genius Grant in 1987,[34] an Alfred P. Sloan Fellowship, and the Klingenstein Fellowship in Neuroscience.[35] He was also awarded the National Science Foundation Presidential Young Investigator Award,[17] the Young Investigator of the Year Awards from the Society for Neuroscience, the International Society for Psychoneuroendocrinology, and the Biological Psychiatry Society.[36]

In 2007 he received the John P. McGovern Award for Behavioral Science, awarded by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[37]

In 2008 he received Wonderfest's Carl Sagan Prize for Science Popularization.[38] In February 2010 Sapolsky was named to the Freedom From Religion Foundation's Honorary Board of distinguished achievers,[39] following the earlier Emperor Has No Clothes Award for year 2002.[40]

Personal life[]

Sapolsky is married to Lisa Sapolsky, a doctor in neuropsychology. They have two children, Benjamin and Rachel.[23]

Works[]

Books[]

- Stress, the Aging Brain, and the Mechanisms of Neuron Death (MIT Press, 1992) ISBN 0-262-19320-5

- Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers (1994, Holt Paperbacks/Owl 3rd Rep. Ed. 2004) ISBN 0-8050-7369-8

- The Trouble with Testosterone: And Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament (Scribner, 1997) ISBN 0-684-83891-5

- Junk Food Monkeys (Headline Publishing, 1997) ISBN 978-0-7472-7676-0 (UK edition of The Trouble with Testosterone)

- A Primate's Memoir (Touchstone Books, 2002) ISBN 0-7432-0247-3

- Monkeyluv: And Other Essays on Our Lives as Animals (Scribner, 2005) ISBN 0-7432-6015-5

- Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst (Penguin Press, May 2017) ISBN 1-5942-0507-8

Video courses[]

- Your Evolved Brain Is at the Mercy of Your Reptilian Impulses and Vice Versa

- Sapolsky, Robert. Human Behavioral Biology, 25 lectures (Last 2 lectures were not taped / included in the official Stanford playlist but older versions/tapings of those lectures are available here).

- Sapolsky, Robert (2010). Stress and Your Body. Chantilly, VA: The Teaching Company. ISBN 978-1-59803-680-0..

- Sapolsky, Robert. Being Human: Life Lessons from the Frontiers of Science.

- Sapolsky, Robert. Biology and Human Behavior: The Neurological Origins of Individuality, 2nd Edition.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Robert Sapolsky at Stanford".

- ^ Hanson, E. Simon (January 5, 2001). "A Conversation With Robert Sapolsky". Brain Connection. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

BC: Who were your greatest mentors? RS: Of people I've actually dealt with, ... the main person is an anthropologist/physician named Melvin Konnor ... . He ... was my advisor in college and remains a major mentor.

- ^ "Robert Sapolsky". Retrieved 22 Feb 2009.

- ^ At home with: Dr. Robert M. Sapolsky; Family Man With a Foot In the Veld, By PATRICIA LEIGH BROWN, New York Times, APRIL 19, 2001

- ^ Vaughan, Christopher. "Going Wild A biologist gets in touch with his inner primate". Stanford Magazine. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Shwartz, Mark (March 7, 2007). "Robert Sapolsky discusses physiological effects of stress". News. Stanford University. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ "Dr. Robert Sapolsky's lecture about Biological Underpinnings of Religiosity".

I was raised in an extremely religious Orthodox upbringing and I had a break with it when I was about 14. That process of completely breaking to the point now where I have no religion have no spirituality I'm utterly atheist, and in passing it is probably the thing I most regret in my life but is something I appear not to be able to change the process of getting to that point I view in retrospect as one of the most defining things in my life the process of turning into that person from who I was.

- ^ Sapolsky, Robert (April 2003). "Belief and Biology". Freedom from Religion Foundation.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sapolsky Lectures on Stress and Health, Oct. 28 in Masur Auditorium - The NIH Record -October 16, 2009". nihrecord.nih.gov.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Professor Robert Sapolsky Bio Page". www.thegreatcourses.com.

- ^ Sapolsky 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Sapolsky 2007, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Sapolsky 2007, p. 88.

- ^ "Transcript of How I Write Conversation with Robert Sapolsky". Stanford University. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ "Stanford Univ. detail of Prof. Sapolsky". Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ Sapolsky, Robert M. (1992). Stress, the Aging Brain, and the Mechanisms of Neuron Death (Bradford Books). ISBN 0262193205.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Rockefeller University names Robert Sapolsky 2008 Lewis Thomas Prize winner". Rockefeller University News. May 19, 2009. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ Sapolsky, Robert M (1990). "Stress in the Wild". Scientific American. 262 (1): 106–13. Bibcode:1990SciAm.262a.116S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0190-116. JSTOR 24996650. PMID 2294581.

- ^ "The Brain on the Stand," New York Times Magazine

- ^ Sapolsky, RM (2004). "The frontal cortex and the criminal justice system". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 359 (1451): 1787–96. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1547. PMC 1693445. PMID 15590619.

- ^ "Stress: Portrait of a Killer". Stress: Portrait of a Killer. Stanford University, National Geographic. 2008. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 25 Aug 2014.

- ^ Springer, Michael (22 August 2012). "Do Yourself a Favor and Watch Stress: Portrait of a Killer (with Stanford Biologist Robert Sapolsky)". openculture.com. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, Patricia Leigh (19 Apr 2001). "AT HOME WITH: DR. ROBERT M. SAPOLSKY; Family Man With a Foot In the Veld". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 Aug 2014.

- ^ Angier, Natalie (13 Apr 2004). "No Time for Bullies: Baboons Retool Their Culture". New York Times Archives. New York Times Company. Retrieved 5 Aug 2014.

- ^ Lehrer, Jonah (28 Jul 2010). "Under Pressure: The Search for a Stress Vaccine". Wired Magazine. Wired.com. Retrieved 25 Aug 2014.

- ^ Vaughan, Christopher (Nov–Dec 2001). "Going Wild". Stanford University Magazine. Stanford University. Retrieved 25 Aug 2014.

- ^ "Racism, inequality, and conflict: an interview with Prof. Robert Sapolsky". Tehran Times. 2020-07-15. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ "People - Robert Sapolsky - Radiolab". www.radiolab.org. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- ^ Joe Rogan (2017-10-18), Joe Rogan Experience #965 - Robert Sapolsky, retrieved 2018-03-20

- ^ "Human Behavioral Biology (Robert Sapolsky) 25 lectures". YouTube. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- ^ Meltzer, Tom (2013-08-27). "The 20 online talks that could change your life". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ Sapolsky, Robert, The biology of our best and worst selves, retrieved 2018-03-20

- ^ Sapolsky, Robert, The uniqueness of humans, retrieved 2018-03-20

- ^ "MacArthur Fellows List - July 1987". Archived from the original on 2008-04-19. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ "Talk to probe roots of stress (03/16/07)". mc.vanderbilt.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ "Science writer Robert Sapolsky to speak about coping with stress April 10". Middlebury. 2009-12-17. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ "About AAAS: John McGovern Lecture". Retrieved 22 Feb 2009.

- ^ "Sagan Prize Recipients". wonderfest.org. 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Honorary FFRF Board Announced". ffrf.org. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ "Emperor Has No Clothes Award -- Robert Sapolsky". Freedom From Religion Foundation. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

Works cited[]

- Sapolsky, Robert M. (2007). A Primate's Memoir: A Neuroscientist's Unconventional Life Among the Baboons (reprint ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-9036-1.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Sapolsky |

- Robert Sapolsky profile at Stanford School of Medicine

- Robert Sapolsky at IMDb

- 1957 births

- Living people

- Jewish atheists

- American atheists

- American neuroscientists

- Jewish neuroscientists

- Jewish American scientists

- American endocrinologists

- MacArthur Fellows

- Stanford University Department of Biology faculty

- Stanford University School of Medicine faculty

- John Dewey High School alumni

- Harvard University alumni

- Sloan Research Fellows

- Rockefeller University alumni

- Scientists from New York (state)