Rodelinda (opera)

Rodelinda, regina de' Longobardi (HWV 19) is an opera seria in three acts composed for the first Royal Academy of Music by George Frideric Handel. The libretto is by Nicola Francesco Haym, based on an earlier libretto by Antonio Salvi. Rodelinda has long been regarded as one of Handel's greatest works.[1]

Performance history[]

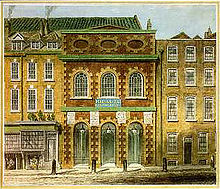

Rodelinda was first performed at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket, London, on 13 February 1725. It was produced with the same singers as Tamerlano. There were 14 performances; it was repeated on 18 December 1725, and again on 4 May 1731, a further 16 performances in all, each revival including changes and fresh material.[2] In 1735 and 1736 it was also performed, with only modest success, in Hamburg at the Oper am Gänsemarkt. The first modern production – in heavily altered form – was in Göttingen on 26 June 1920 where it was the first of a series of modern Handel opera revivals produced by the Handel enthusiast Oskar Hagen.[2] The opera reached the US in 1931 and was revived in London in 1939.[3] A further notable London revival by the Handel Opera Society, in English and using a cut text, including both Joan Sutherland and Janet Baker in the cast, conducted by , was performed in June 1959.[3] With the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s, Rodelinda, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[4] Among other performances, Rodelinda was staged at the Glyndebourne Festival in the UK in 1998,[5] by the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 2004[6] and by English National Opera in 2014.[7] The ENO production was revived at the Bolshoi Theatre in 2015.[8] The Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona, performed the opera in March 2019, with Lisette Oropesa and Bejun Mehta in the leading roles.[9] The Dutch National Opera staged Rodelinda in January 2020, with Lucy Crowe and Bejun Mehta in the leading roles.[10]

Roles[]

| Role[2] | Voice type | Premiere cast, 13 February 1725 |

|---|---|---|

| Rodelinda, Queen of Lombardy | soprano | Francesca Cuzzoni |

| Bertarido, usurped King of Lombardy | alto castrato | Francesco Bernardi, called "Senesino" |

| Grimoaldo, Duke of Benevento, Bertarido's usurper | tenor | Francesco Borosini |

| Eduige, Bertarido's sister, betrothed to Grimoaldo | contralto | Anna Vincenza Dotti |

| Unulfo, Bertarido's friend and counsellor | alto castrato | Andrea Pacini |

| Garibaldo, Grimoaldo's counsellor, duke of Turin | bass | Giuseppe Maria Boschi |

| Flavio, Rodelinda's son | silent |

Synopsis[]

The argument[]

Prior to the opening of the opera, Grimoaldo has defeated Bertarido, King of Lombardy, in battle and has usurped the throne of Milan. Bertarido has fled, leaving his wife Rodelinda and his son Flavio prisoners of the usurper in the royal palace. Failing to secure support to recover his crown, Bertarido has caused it to be reported that he has died in exile, a ruse to be used in an attempt to rescue his wife and son.

Act 1[]

Rodelinda's apartments[]

Alone in the palace, Rodelinda mourns the loss of her husband Bertarido. The usurper Grimoaldo enters, declaring a long-hidden passion for her. He proposes marriage and offers her back the throne that is rightfully hers. She angrily rejects him (Aria: "L'empio rigor del fato"). Eduige arrives at the apartment looking for Grimoaldo. Grimoaldo, having previously been betrothed to Bertarido's sister Eduige, now tells her that as she once spurned him, he shall spurn her. After Grimoaldo leaves, the scheming Garibaldo, his counsellor, professes love for Eduige. She promises to return his love once she has had revenge on Grimoaldo (Aria: "Lo farò, diro: spietato"). Alone, Garibaldo reveals that his love for Eduige is feigned, and is part of a plan to gain the throne for himself (Aria: "Di cupido impiego i vanni").

A cypress-grove[]

Bertarido, in hiding nearby, reads the inscription on his own memorial and longs for his beloved wife Rodelinda (Aria: "Dove sei, amato bene?"). Along with his friend and counsellor Unulfo, he secretly watches as Rodelinda and Flavio, her son, arrive to lay flowers at his memorial. She weeps at her husband's fate. Garibaldo enters with an ultimatum for Rodelinda: either she agrees to marry Grimoaldo, or her son will be put to death. Rodelinda consents but also vows to demand Garibaldo's death when she returns to the throne. Bertarido, still watching, is aghast and takes Rodelinda's decision as an act of personal betrayal.

Act 2[]

A great hall[]

Garibaldo taunts Eduige, telling her that now, since she has lost Grimoaldo, she has missed her chance to become queen. Eduige satirically congratulates Rodelinda, noting her sudden decision to betray her husband's memory and marry his usurper. Rodelinda reminds Eduige of who is queen. Eduige vows vengeance on Grimoaldo. Eduige departs and Grimoaldo enters. Rodelinda sets out her terms for marrying Grimoaldo: he must kill Flavio with his own hands in front of her. Grimoaldo, horrified, refuses. After Rodelinda leaves, Garibaldo encourages Grimoaldo to carry out the murder and take Rodelinda as his wife, but Grimoaldo rejects the advice. He says that Rodelinda's act of courage and determination has made him love her all the more, though he has now lost hope of ever winning her. When the two advisors are alone, Unulfo asks Garibaldo how he could give a king such advice, and Garibaldo expounds his tyrannical perspective on the use of power (Aria: "Tirannia gliel diede il regno").

A delightful prospect[]

Bertarido approaches the palace grounds in disguise, where his sister Eduige recognizes his voice. Unolfo brings word of Rodelinda's fidelity – also gratifying for Eduige – and Eduige agrees to help Bertarido rescue his wife and son. Unolfo promises to pass a message to Rodelinda that her husband is still alive. Bertarido rejoices at the prospect of reunion.

A gallery in Rodelinda's apartment[]

Rodelinda and Bertarido meet in secret, and are discovered in an embrace by Grimoaldo who fails to recognise her husband. Grimoaldo is outraged, believing that Rodelinda has taken a lover. To save her honour, Bertarido reveals his identity but Grimoaldo vows to kill him anyway, whoever he may be. The spouses bid each other a last farewell (Duet: "Io t'abbraccio").

Act 3[]

A gallery[]

Unulfo and Eduige make a plan to release Bertarido from prison: they will smuggle to him a sword and the key to a secret passage that runs under the palace. Garibaldo advises Grimoaldo to put the unknown man – whether Bertarido or not – to death. Grimoaldo is racked by jealousy, passion and fear.

A very dark prison[]

Languishing in prison, Bertarido receives the sword, the key and a written note. When Unulfo comes to release him, Bertarido mistakes the visitor in the darkness for the executioner and wounds him with the sword. Unulfo shrugs the injury off, and the two leave. Eduige guides Rodelinda into the cell. Finding it empty and with blood on the floor, they fear that Bertarido is dead.

A royal garden[]

Grimoaldo is tormented by remorse and flees to the palace garden, hoping to find a peaceful spot where he can seek solace in sleep (Aria: "Pastorello d'un povero armento"). Garibaldo, finding him unprotected, decides to kill him. Bertarido appears and kills the intended assassin; Grimoaldo, however, he spares (Aria: "Vivi, tiranno!"). Grimoaldo renounces his claim to the throne of Milan, and pledges himself once again to Eduige. He offers the throne back to Bertarido who accepts it once he is assured that his wife and son will be returned to him. There is general rejoicing.[11]

Sources[]

The opera's libretto is by Nicola Francesco Haym, and was based on an earlier libretto by Antonio Salvi that had been set by Giacomo Antonio Perti in 1710. Salvi's libretto was derived from Pierre Corneille's tragedy Pertharite, roi des Lombards (1652), which dealt with the history of Perctarit, king of the Lombards. The ultimate origin of the story, as of Handel's Flavio, is Paul the Deacon's eighth-century work Gesta Langobardorum.[12] In the opera, 'Pertharite' becomes 'Bertarido'.

Context and analysis[]

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present-day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[13][14]

Within a year, 1724–1725, Handel wrote three great operas in succession for the Royal Academy of Music, each with Senesino and Francesca Cuzzoni as the stars, the other two being Giulio Cesare and Tamerlano.[15]

Horace Walpole wrote of Cuzzoni in Rodelinda:

She was short and squat, with a doughy cross face, but fine complexion; was not a good actress; dressed ill; and was silly and fantastical. And yet on her appearing in this opera, in a brown silk gown trimmed with silver, with the vulgarity and indecorum of which all the old ladies were much scandalised, the young adopted it as a fashion, so universally, that it seemed a national uniform for youth and beauty.[15]

To 18th century musicologist Charles Burney, Rodelinda "contains such a number of capital and pleasing airs, as entitles it to one of the first places among Handel's dramatic productions". Burney notes particularly the aria for Bertarido in act 1, "Dove sei, amato bene", calling it "one of the finest pathetic airs that can be found in all his works... This air is rendered affecting by new and curious modulation, as well as by the general cast of the melody."[16] This aria is also sometimes sung as a solo piece in English, to an unrelated text – "Art thou troubled?" – by W. G. Rothery, written in 1910.[17][18]

The opera is scored for two recorders, flute, two oboes, bassoon, two horns, strings and continuo (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Recordings[]

Audio recordings[]

| Year | Cast: Rodelinda, Bertarido, Grimoaldo, Eduige, Unolfo, Garibaldo |

Conductor, orchestra |

Label[19][20] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | Joan Sutherland, Margreta Elkins, Alfred Hallett, Janet Baker, Patricia Kern, Raimund Herincx |

, Philomusica Orchestra |

CD:Andromeda Cat:ANDRCD9075 |

| 1964 | Teresa Stich-Randall, Maureen Forrester, Alexander Young, Hilde Rössel-Majdan, Helen Watts, John Boyden |

Brian Priestman, Vienna Radio Orchestra |

CD:The Westminster Legacy Cat:DG 4792343 |

| 1985 | Joan Sutherland, Alicia Nafé, Curtis Rayam, Isobel Buchanan, Huguette Tourangeau, Samuel Ramey |

Richard Bonynge Welsh National Opera Orchestra |

CD:Australian Eloquence Cat: ELQ4806105 |

| 1996 | Sophie Daneman, Daniel Taylor, Adrian Thompson, Catherine Robbin, Robin Blaze, Christopher Purves |

Nicholas Kraemer Raglan Baroque Players |

CD:Virgin Classics Veritas Cat: 45277 |

| 2004 | Simone Kermes, Marijana Mijanovic, Steve Davislim, Sonia Prina, Marie-Nicole Lemieux, Vito Priante |

Alan Curtis Il Complesso Barocco |

CD:DG Archiv Cat:4775391 |

| 2016 | Sonia Ganassi, Franco Fagioli, Paolo Fanale, Marina De Liso, Antonio Giovannini, Gezim Myshketa |

Diego Fasolis Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia |

CD:Dynamic Cat:CDS7724 |

Video recordings[]

| Year | Cast: Rodelinda,Bertarido, Grimoaldo, Eduige, Unolfo, Garibaldo |

Conductor, orchestra |

Stage director | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Anna Caterina Antonacci, Andreas Scholl, Kurt Streit, Louise Winter, Artur Stefanowicz. Umberto Chiummo |

William Christie Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment |

Jean-Marie Villegier | DVD:Warner Classics Cat:3984230242 |

| 2003 | Dorothea Röschmann, Michael Chance, Paul Nilon, Felicity Palmer, Christopher Robson, Umberto Chiummo |

Ivor Bolton Bavarian State Opera Orchestra |

David Alden | DVD:Farao Cat:D108060 |

| 2012 | Renée Fleming, Andreas Scholl, Joseph Kaiser, Stephanie Blythe, Iestyn Davies, Shenyang |

Harry Bicket Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, (Recording of a performance at the MET on 3 December 2011) |

Stephen Wadsworth | DVD:Decca Cat:0743469 |

| 2019 | Jeanine de Bique, Tim Mead, Benjamin Hulett, Avery Amereau, Jakub Józef Orliński, Andrea Mastroni |

Emmanuelle Haïm, Le Concert d'Astrée |

Jean Bellorini | DVD:Erato Records Cat:9029541988 |

References[]

Notes

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (December 4, 2004). "Handel Discovers Big Home at the Met". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

'Rodelinda,' first performed in 1725, has long been considered one of Handel's greatest works, and rightly so.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "G. F. Handel's Compositions". GF Handel.org. Handel Institute. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadie, Stanley (2009). Grove Book of Operas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195387117.

- ^ "Handel:A Biographical Introduction". GF Handel.org. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Ashley, Tim (15 June 2004). "Rodelinda". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "GP at The Met: Rodelinda". PBS.org. PBS. 3 April 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Maddocks, Fiona. "Rodelinda review – as restrained as it is over the top". The Observer. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Bolshoi Theatre (13 December 2015). Press release: "A Lively Story". Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ "RODELINDA | Liceu Opera Barcelona". www.liceubarcelona.cat. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "Rodelinda | De Nationale Opera". www.operaballet.nl. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ Leon, Donna. "Handel House - Handel's Operas: Rodelinda". Handel and Hendrix. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Dean & Knapp 1995, p. 574.

- ^ Dean & Knapp 1995, p. 298.

- ^ Strohm, Reinhard (20 June 1985). Essays on Handel and Italian opera by Reinhard Strohm. ISBN 9780521264280. Retrieved 2013-02-02 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Rodelinda". handelhendrix.org. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Charles Burney: A General History of Music: from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Vol. 4. London 1789, reprint: Cambridge University Press 2010, ISBN 978-1-1080-1642-1, p. 301.

- ^ "Art thou troubled? Music will calm thee (Anonymous, set by Georg Friedrich Händel) (The LiederNet Archive: Texts and Translations to Lieder, mélodies, canzoni, and other classical vocal music)". www.lieder.net. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ "Art Thou Troubled? (Dove sei?)", description and sheet music, Boosey & Hawkes

- ^ "Recordings of Rodelinda". Operadis.org.uk. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "Recordings of Rodelinda". Prestoclassical.co.uk. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

Sources

- Dean, Winton; Knapp, J. Merrill (1995). Handel's Operas, 1704–1726. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198164418.

Further reading[]

- Hicks, Anthony, "Rodelinda", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, ed. Stanley Sadie (London, 1992) ISBN 0-333-73432-7

External links[]

- Italian libretto

- Rodelinda: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Score of Rodelinda (ed. Friedrich Chrysander, Leipzig 1876)

- Operas by George Frideric Handel

- Italian-language operas

- Opera seria

- 1725 operas

- Operas

- Operas based on works by Pierre Corneille