Romanian language

| Romanian | |

|---|---|

| Daco-Romanian | |

| limba română | |

| Pronunciation | [roˈmɨnə] |

| Native to | Romania, Moldova |

| Ethnicity | Romanians (including Moldovans) |

Native speakers | 24–26 million (2016)[1] Second language: 4 million[2] L1+L2 speakers: 28–30 million |

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

| Dialects | |

Writing system | Latin (Romanian alphabet) Cyrillic (Transnistria only) Romanian Braille |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Romanian Academy Academy of Sciences of Moldova |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ro |

| ISO 639-2 | rum (B) ron (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ron |

| Glottolog | roma1327 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAD-c (varieties: 51-AAD-ca to -ck) |

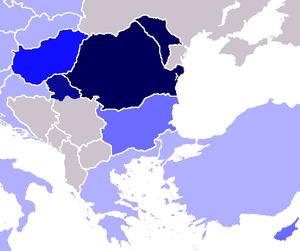

Blue: region where Romanian is the dominant language. Green: areas with a notable minority of Romanian speakers. | |

Distribution of the Romanian language in Romania, Moldova and surroundings. | |

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: limba română [ˈlimba roˈmɨnə] (![]() listen), or românește, lit. 'in Romanian') is a Balkan Romance language spoken by approximately 24–26 million people[3][4] as a native language, primarily in Romania and Moldova, and by another 4 million people as a second language.[5][6] According to another estimate, there are about 34 million people worldwide who can speak Romanian, of whom 30 million speak it as a native language.[7] It is an official and national language of both Romania and Moldova and is one of the official languages of the European Union.

listen), or românește, lit. 'in Romanian') is a Balkan Romance language spoken by approximately 24–26 million people[3][4] as a native language, primarily in Romania and Moldova, and by another 4 million people as a second language.[5][6] According to another estimate, there are about 34 million people worldwide who can speak Romanian, of whom 30 million speak it as a native language.[7] It is an official and national language of both Romania and Moldova and is one of the official languages of the European Union.

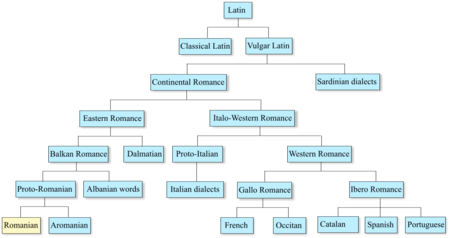

Romanian is a part of the Eastern Romance sub-branch of Romance languages, a linguistic group that evolved from several dialects of Vulgar Latin which separated from the Western Romance languages in the course of the period from the 5th to the 8th centuries.[8] To distinguish it within the Eastern Romance languages, in comparative linguistics it is called Daco-Romanian as opposed to its closest relatives, Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian. Romanian is also known as Moldovan in Moldova, although the Constitutional Court of Moldova ruled in 2013 that "the official language of the republic is Romanian".[nb 1]

Numerous immigrant Romanian speakers live scattered across many other regions and countries worldwide, with large populations in Italy, Spain, Germany, United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States.

History[]

Prehistory[]

Romanian descended from the Vulgar Latin spoken in the Roman provinces of Southeastern Europe.[9] Roman inscriptions show that Latin was primarily used to the north of the so-called Jireček Line (a hypothetical boundary between the predominantly Latin- and Greek-speaking territories of the Balkan Peninsula in the Roman Empire), but the exact territory where Proto-Romanian (or Common Romanian) developed cannot certainly be determined.[9][10] Most regions where Romanian is now widely spoken—Bessarabia, Bukovina, Crișana, Maramureș, Moldova, and significant parts of Muntenia—were not incorporated in the Roman Empire.[11] Other regions—Banat, western Muntenia, Oltenia and Transylvania—formed the Roman province of Dacia Traiana for about 170 years.[11] According to the "continuity theory", the venue of the development of Proto-Romanian included the lands now forming Romania (to the north of the Danube), the opposite "immigrationist" theory says that Proto-Romanian was spoken in the lands to the south of the Danube and Romanian-speakers settled in most parts of modern Romania only centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire.[9][11][disputed ]

Most scholars agree that two major dialects developed from Common Romanian by the 10th century.[9] Daco-Romanian (the official language of Romania and Moldova) and Istro-Romanian (a language spoken by no more than 2,000 people in Istria) descended from the northern dialect.[9] Two other languages, Aromanian and Megleno-Romanian, developed from the southern version of Common Romanian.[9] These two languages are now spoken in lands to the south of the Jireček Line.[11]

Early history[]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: This section presents modern Romanian translations as if they were historical sources. (January 2018) |

The use of the denomination Romanian (română) for the language and use of the demonym Romanians (Români) for speakers of this language predates the foundation of the modern Romanian state. Romanians always used the general term "rumân/român" or regional terms like "ardeleni" (or "ungureni"), "moldoveni" or "munteni" to designate themselves. Both the name of "rumână" or "rumâniască" for the Romanian language and the self-designation "rumân/român" are attested as early as the 16th century, by various foreign travelers into the Carpathian Romance-speaking space,[12] as well as in other historical documents written in Romanian at that time such as Cronicile Țării Moldovei (The Chronicles of the land of Moldova) by Grigore Ureche.

An attested reference to Romanian comes from a Latin title of an oath made in 1485 by the Moldavian Prince Stephen the Great to the Polish King Casimir, in which it is reported that "Haec Inscriptio ex Valachico in Latinam versa est sed Rex Ruthenica Lingua scriptam accepta"—This Inscription was translated from Valachian (Romanian) into Latin, but the King has received it written in the Ruthenian language (Slavic).[13][14]

The oldest extant document written in Romanian remains Neacșu's letter (1521) and was written using the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, which was used until the late 19th century.

In 1534, notes: "Valachi nunc se Romanos vocant" (The Wallachians are now calling themselves Romans).[15] Francesco della Valle writes in 1532 that Romanians are calling themselves Romans in their own language, and he subsequently quotes the expression: "Sti Rominest?" for "Știi Românește?" (Do you know Romanian?).[16]

The Transylvanian Saxon writes in 1542 that "Vlachi" call themselves "Romuini".[17]

The Polish chronicler Stanislaw Orzechowski (Orichovius) notes in 1554 that In their language they call themselves Romini from the Romans, while we call them Wallachians from the Italians).[18]

The Croatian prelate and diplomat Antun Vrančić recorded in 1570 that "Vlachs in Transylvania, Moldavia and Wallachia designate themselves as "Romans".[19]

writes in 1574 that those who live in Moldavia, Wallachia and the vast part of Transylvania, "consider themselves as true descendants of the Romans and call their language romanechte, which is Roman".[20]

After travelling through Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania accounts in 1575 that the indigenous population of these regions call themselves "romanesci" ("românești").[21]

In Palia de la Orăștie (1582) stands written ".[...] că văzum cum toate limbile au și înfluresc întru cuvintele slăvite a lui Dumnezeu numai noi românii pre limbă nu avem. Pentru aceia cu mare muncă scoasem de limba jidovească si grecească si srâbească pre limba românească 5 cărți ale lui Moisi prorocul si patru cărți și le dăruim voo frați rumâni și le-au scris în cheltuială multă... și le-au dăruit voo fraților români,... și le-au scris voo fraților români"[22] and in Letopisețul Țării Moldovei written by the Moldavian chronicler Grigore Ureche we can read: «În Țara Ardialului nu lăcuiesc numai unguri, ce și sași peste seamă de mulți și români peste tot locul...» ("In Transylvania there live not solely Hungarians or Saxons, but overwhelmingly many Romanians everywhere around.").[23]

Miron Costin, in his De neamul moldovenilor (1687), while noting that Moldavians, Wallachians, and the Romanians living in the Kingdom of Hungary have the same origin, says that although people of Moldavia call themselves Moldavians, they name their language Romanian (românește) instead of Moldavian (moldovenește).[24]

The Transylvanian Hungarian Martin Szentiványi in 1699 quotes the following: «Si noi sentem Rumeni» ("We too are Romanians") and «Noi sentem di sange Rumena» ("We are of Romanian blood").[25] Notably, Szentiványi used Italian-based spellings to try to write the Romanian words.

Dimitrie Cantemir, in his Descriptio Moldaviae (Berlin, 1714), points out that the inhabitants of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania spoke the same language. He notes, however, some differences in accent and vocabulary.[26] Cantemir's work provides one of the earliest histories of the language, in which he notes, like Ureche before him, the evolution from Latin and notices the Greek and Polish borrowings. Additionally, he introduces the idea that some words must have had Dacian roots. Cantemir also notes that while the idea of a Latin origin of the language was prevalent in his time, other scholars considered it to have derived from Italian.

The slow process of Romanian establishing itself as an official language, used in the public sphere, in literature and ecclesiastically, began in the late 15th century and ended in the early decades of the 18th century, by which time Romanian had begun to be regularly used by the Church. The oldest Romanian texts of a literary nature are religious manuscripts (Codicele Voronețean, Psaltirea Scheiană), translations of essential Christian texts. These are considered either propagandistic results of confessional rivalries, for instance between Lutheranism and Calvinism, or as initiatives by Romanian monks stationed at Peri Monastery in Maramureș to distance themselves from the influence of the Mukacheve eparchy in Ukraine.[27]

Modern history of Romanian in Bessarabia[]

The first Romanian grammar was published in Vienna in 1780.[28] Following the annexation of Bessarabia by Russia (after 1812), Moldavian was established as an official language in the governmental institutions of Bessarabia, used along with Russian,[29] The publishing works established by Archbishop Gavril Bănulescu-Bodoni were able to produce books and liturgical works in Moldavian between 1815 and 1820.[30]

The linguistic situation in Bessarabia from 1812 to 1918 was the gradual development of bilingualism. Russian continued to develop as the official language of privilege, whereas Romanian remained the principal vernacular.

The period from 1905 to 1917 was one of increasing linguistic conflict, with the re-awakening of Romanian national consciousness. In 1905 and 1906, the Bessarabian zemstva asked for the re-introduction of Romanian in schools as a "compulsory language", and the "liberty to teach in the mother language (Romanian language)". At the same time, Romanian-language newspapers and journals began to appear, such as Basarabia (1906), Viața Basarabiei (1907), Moldovanul (1907), Luminătorul (1908), Cuvînt moldovenesc (1913), Glasul Basarabiei (1913). From 1913, the synod permitted that "the churches in Bessarabia use the Romanian language". Romanian finally became the official language with the Constitution of 1923.

Historical grammar[]

Romanian has preserved a part of the Latin declension, but whereas Latin had six cases, from a morphological viewpoint, Romanian has only five: the nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, and marginally the vocative. Romanian nouns also preserve the neuter gender, although instead of functioning as a separate gender with its own forms in adjectives, the Romanian neuter became a mixture of masculine and feminine. The verb morphology of Romanian has shown the same move towards a compound perfect and future tense as the other Romance languages. Compared with the other Romance languages, during its evolution, Romanian simplified the original Latin tense system in extreme ways,[31][unreliable source?] in particular the absence of sequence of tenses.[32]

Geographic distribution[]

| Country | Speakers (%) |

Speakers (native) |

Country Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | |||

| World | 0.33% | 23,623,890 | 7,035,000,000 |

| official: | |||

| Countries where Romanian is an official language | |||

| Romania | 90.65% | 17,263,561[33] | 19,043,767 |

| Moldova 2 | 82.1% | 2,184,065 | 2,681,735 |

| Transnistria (Eastern Moldova) 3 | 33.0% | 156,600 | 475,665 |

| Vojvodina (Serbia) | 1.32% | 29,512 | 1,931,809 |

| minority regional co-official language: | |||

| Ukraine 5 | 0.8% | 327,703 | 48,457,000 |

| not official: | |||

| Other neighboring European states (except for CIS where Romanian is not official) | |||

| Hungary | 0.14% | 13,886[34] | 9,937,628 |

| Central Serbia | 0.4% | 35,330 | 7,186,862 |

| Bulgaria | 0.06% | 4,575[35][full citation needed] | 7,364,570 |

| Other countries in Europe (except for CIS) | |||

| Italy | 1.86% | 1,131,839[36] | 60,795,612 |

| Germany | 0.9% | 748,225[37] | 83,517,045 |

| Spain | 1.4% | 671,985[38] | 46,754,778 |

| United Kingdom | 0.6% | 427,000[39] | 67,530,172 |

| France | 0.07% | 50,000[40] | 65,350,000 |

| Belgium | 0.45% | 45,877[41] | 10,296,350 |

| Austria | 0.45% | 36,000[42] | 8,032,926 |

| Greece | 0.36% | 35,295[43] | 9,903,268 |

| Portugal | 0.3% | 31,065[44] | 10,226,187 |

| Cyprus | 2.91% | 24,376[45] | 838,897 |

| Ireland | 0.45% | 20,625[46] | 4,588,252 |

| Rest of Europe | 0.07% | 75,000[47] | 114,050,000 |

| CIS | |||

| not official: | |||

| Russia 1 | 0.12% | 159,601[48] | 142,856,536 |

| Kazakhstan 1 | 0.1% | 14,666 | 14,953,126 |

| Asia | |||

| Israel | 2.86% | 208,400 | 7,412,200 |

| UAE | 0.1% | 5,000 | 4,106,427 |

| Singapore | 0.02% | 1,400 | 5,535,000 |

| Japan | 0.002% | 2,185 | 126,659,683 |

| South Korea | 0.0006% | 300 | 50,004,441 |

| China | 0.0008% | 12,000 | 1,376,049,000 |

| The Americas | |||

| not official: | |||

| United States | 0.10% | 340,000 | 315,091,138 |

| Canada | 0.7% | 238,050 | 35,151,728 |

| Argentina | 0.03% | 13,000 | 40,117,096 |

| Venezuela | 0.036% | 10,000 | 27,150,095 |

| Brazil | 0.002% | 4,000 | 190,732,694 |

| Oceania | |||

| not official: | |||

| Australia | 0.09% | 10,897[49] | 21,507,717 |

| New Zealand | 0.08% | 3,100 | 4,027,947 |

| Africa | |||

| not official: | |||

| South Africa | 0.007% | 3,000 | 44,819,778 |

|

1 Many are Moldavians who were deported | |||

Romanian is spoken mostly in Central and the Balkan region of Southern Europe, although speakers of the language can be found all over the world, mostly due to emigration of Romanian nationals and the return of immigrants to Romania back to their original countries. Romanian speakers account for 0.5% of the world's population,[51] and 4% of the Romance-speaking population of the world.[52]

Romanian is the single official and national language in Romania and Moldova, although it shares the official status at regional level with other languages in the Moldovan autonomies of Gagauzia and Transnistria. Romanian is also an official language of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina in Serbia along with five other languages. Romanian minorities are encountered in Serbia (Timok Valley), Ukraine (Chernivtsi and Odessa oblasts), and Hungary (Gyula). Large immigrant communities are found in Italy, Spain, France, and Portugal.

In 1995, the largest Romanian-speaking community in the Middle East was found in Israel, where Romanian was spoken by 5% of the population.[53][54] Romanian is also spoken as a second language by people from Arabic-speaking countries who have studied in Romania. It is estimated that almost half a million Middle Eastern Arabs studied in Romania during the 1980s.[55] Small Romanian-speaking communities are to be found in Kazakhstan and Russia. Romanian is also spoken within communities of Romanian and Moldovan immigrants in the United States, Canada and Australia, although they do not make up a large homogeneous community statewide.

Legal status[]

In Romania[]

According to the Constitution of Romania of 1991, as revised in 2003, Romanian is the official language of the Republic.[56]

Romania mandates the use of Romanian in official government publications, public education and legal contracts. Advertisements as well as other public messages must bear a translation of foreign words,[57] while trade signs and logos shall be written predominantly in Romanian.[58]

The Romanian Language Institute (Institutul Limbii Române), established by the Ministry of Education of Romania, promotes Romanian and supports people willing to study the language, working together with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Department for Romanians Abroad.[59]

Since 2013, the Romanian Language Day is celebrated on every 31 August.[60][61]

In Moldova[]

Romanian is the official language of the Republic of Moldova. The 1991 Declaration of Independence names the official language Romanian.[62][63] The Constitution of Moldova names the state language of the country Moldovan. In December 2013, a decision of the Constitutional Court of Moldova ruled that the Declaration of Independence takes precedence over the Constitution and the state language should be called Romanian.[64]

Scholars agree that Moldovan and Romanian are the same language, with the glottonym "Moldovan" used in certain political contexts.[65] It has been the sole official language since the adoption of the Law on State Language of the Moldavian SSR in 1989.[66] This law mandates the use of Moldovan in all the political, economical, cultural and social spheres, as well as asserting the existence of a "linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity".[67] It is also used in schools, mass media, education and in the colloquial speech and writing. Outside the political arena the language is most often called "Romanian". In the breakaway territory of Transnistria, it is co-official with Ukrainian and Russian.

In the 2014 census, out of the 2,804,801 people living in Moldova, 24% (652,394) stated Romanian as their most common language, whereas 56% stated Moldovan. While in the urban centers speakers are split evenly between the two names (with the capital Chișinău showing a strong preference for the name "Romanian", i.e. 3:2), in the countryside hardly a quarter of Romanian/Moldovan speakers indicated Romanian as their native language.[68] Unofficial results of this census first showed a stronger preference for the name Romanian, however the initial reports were later dismissed by the Institute for Statistics, which led to speculations in the media regarding the forgery of the census results.[69]

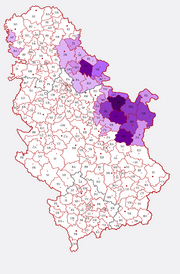

In Vojvodina, Serbia[]

| 1–5% 5–10% 10–15% | 15–25% 25–35% over 35% |

The Constitution of the Republic of Serbia determines that in the regions of the Republic of Serbia inhabited by national minorities, their own languages and scripts shall be officially used as well, in the manner established by law.[70]

The Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina determines that, together with the Serbian language and the Cyrillic script, and the Latin script as stipulated by the law, the Croat, Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian and Rusyn languages and their scripts, as well as languages and scripts of other nationalities, shall simultaneously be officially used in the work of the bodies of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, in the manner established by the law.[71] The bodies of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina are: the Assembly, the Executive Council and the Provincial administrative bodies.[72]

The Romanian language and script are officially used in eight municipalities: Alibunar, Bela Crkva (Romanian: Biserica Albă), Žitište (Zitiște), Zrenjanin (Zrenianin), Kovačica (Kovăcița), Kovin (Cuvin), Plandište (Plandiște) and Sečanj. In the municipality of Vršac (Vârșeț), Romanian is official only in the villages of Vojvodinci (Voivodinț), Markovac (Marcovăț), Straža (Straja), Mali Žam (Jamu Mic), Malo Središte (Srediștea Mică), Mesić (Mesici), Jablanka, Sočica (Sălcița), Ritiševo (Râtișor), Orešac (Oreșaț) and Kuštilj (Coștei).[73]

In the 2002 Census, the last carried out in Serbia, 1.5% of Vojvodinians stated Romanian as their native language.

Regional language status in Ukraine[]

In parts of Ukraine where Romanians constitute a significant share of the local population (districts in Chernivtsi, Odessa and Zakarpattia oblasts) Romanian is taught in schools as a primary language and there are Romanian-language newspapers, TV, and radio broadcasting.[74][75] The University of Chernivtsi in western Ukraine trains teachers for Romanian schools in the fields of Romanian philology, mathematics and physics.[76]

In Hertsa Raion of Ukraine as well as in other villages of Chernivtsi Oblast and Zakarpattia Oblast, Romanian has been declared a "regional language" alongside Ukrainian as per the 2012 legislation on languages in Ukraine.

In other countries and organizations[]

Romanian is an official or administrative language in various communities and organisations, such as the Latin Union and the European Union. Romanian is also one of the five languages in which religious services are performed in the autonomous monastic state of Mount Athos, spoken in the monk communities of Prodromos and Lakkoskiti. In the unrecognised state of Transnistria, Moldovan is one of the official languages. However, unlike all other dialects of Romanian, this variety of Moldovan is written in Cyrillic Script.

As a second and foreign language[]

Romanian is taught in some areas that have Romanian minority communities, such as Vojvodina in Serbia, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Hungary. The Romanian Cultural Institute (ICR) has since 1992 organised summer courses in Romanian for language teachers.[77] There are also non-Romanians who study Romanian as a foreign language, for example the Nicolae Bălcescu High-school in Gyula, Hungary.

Romanian is taught as a foreign language in tertiary institutions, mostly in European countries such as Germany, France and Italy, and the Netherlands, as well as in the United States. Overall, it is taught as a foreign language in 43 countries around the world.[78]

| native | above 3% | between 1–3% | under 1% | n/a |

Popular culture[]

Romanian has become popular in other countries through movies and songs performed in the Romanian language. Examples of Romanian acts that had a great success in non-Romanophone countries are the bands O-Zone (with their No. 1 single Dragostea Din Tei/Numa Numa across the world in 2003–2004), Akcent (popular in the Netherlands, Poland and other European countries), Activ (successful in some Eastern European countries), DJ Project (popular as clubbing music) SunStroke Project (known by viral video "Epic sax guy") and Alexandra Stan (worldwide no.1 hit with "Mr. Saxobeat)" and Inna as well as high-rated movies like 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, 12:08 East of Bucharest or California Dreamin' (all of them with awards at the Cannes Film Festival).

Also some artists wrote songs dedicated to the Romanian language. The multi-platinum pop trio O-Zone (originally from Moldova) released a song called "Nu mă las de limba noastră" ("I won't forsake our language"). The final verse of this song, Eu nu mă las de limba noastră, de limba noastră cea română is translated in English as "I won't forsake our language, our Romanian language". Also, the Moldovan musicians Doina and Ion Aldea Teodorovici performed a song called "The Romanian language".

Dialects[]

Romanian[79] encompasses four varieties: (Daco-)Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian with Daco-Romanian being the standard variety. The origin of the term "Daco-Romanian" can be traced back to the first printed book of Romanian grammar in 1780,[28] by Samuil Micu and Gheorghe Șincai. There, the Romanian dialect spoken north of the Danube is called lingua Daco-Romana to emphasize its origin and its area of use, which includes the former Roman province of Dacia, although it is spoken also south of the Danube, in Dobrudja, Central Serbia and northern Bulgaria.

This article deals with the Romanian (i.e. Daco-Romanian) language, and thus only its dialectal variations are discussed here. The differences between the regional varieties are small, limited to regular phonetic changes, few grammar aspects, and lexical particularities. There is a single written standard (literary) Romanian language used by all speakers, regardless of region. Like most natural languages, Romanian dialects are part of a dialect continuum. The dialects of Romanian are also referred to as sub-dialects and are distinguished primarily by phonetic differences. Romanians themselves speak of the differences as accents or speeches (in Romanian: accent or grai).[80]

Depending on the criteria used for classifying these dialects, fewer or more are found, ranging from 2 to 20, although the most widespread approaches give a number of five dialects. These are grouped into two main types, southern and northern, further divided as follows:

- The southern type has only one member:

- the Wallachian dialect, spoken in the southern part of Romania, in the historical regions of Muntenia, Oltenia and the southern part of Northern Dobruja, but also extending in the southern parts of Transylvania.

- The northern type consists of several dialects:

- the Moldavian dialect, spoken in the historical region of Moldavia, now split among Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine (Bukovina and Bessarabia), as well as northern part of Northern Dobruja;

- the Banat dialect, spoken in the historical region of Banat, including parts of Serbia;

- a group of finely divided and transition-like Transylvanian varieties, among which two are most often distinguished, those of Crișana and Maramureș.

Over the last century, however, regional accents have been weakened due to mass communication and greater mobility.

Some argots and speech forms have also arisen from the Romanian language. Examples are the Gumuțeasca, spoken in Mărgău,[81][82] and the Totoiana, an inverted "version" of Romanian spoken in Totoi.[83][84][85]

Classification[]

Romance language[]

Romanian is a Romance language, belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family, having much in common with languages such as Italian, Spanish, French and Portuguese.[86]

However, the languages closest to Romanian are the other Balkan Romance languages, spoken south of the Danube: Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian. An alternative name for Romanian used by linguists to disambiguate with the other Balkan Romance languages is "Daco-Romanian", referring to the area where it is spoken (which corresponds roughly to the onetime Roman province of Dacia).

Compared with the other Romance languages, the closest relative of Romanian is Italian.[86] Romanian has had a greater share of foreign influence than some other Romance languages such as Italian in terms of vocabulary and other aspects. A study conducted by Mario Pei in 1949 which analyzed the degree of differentiation of languages from their parental language (in the case of Romance languages to Latin comparing phonology, inflection, discourse, syntax, vocabulary, and intonation) produced the following percentages (the higher the percentage, the greater the distance from Latin):[87]

- Sardinian: 8%

- Italian: 12%

- Spanish: 20%

- Romanian: 23.5%

- Occitan: 25%

- Portuguese: 31%

- French: 44%

The lexical similarity of Romanian with Italian has been estimated at 77%, followed by French at 75%, Sardinian 74%, Catalan 73%, Portuguese and Rhaeto-Romance 72%, Spanish 71%.[88]

The Romanian vocabulary became predominantly influenced by French and, to a lesser extent, Italian in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[89]

Balkan language area[]

The Dacian language was an Indo-European language spoken by the ancient Dacians, mostly north of the Danube river but also in Moesia and other regions south of the Danube. It may have been the first language to influence the Latin spoken in Dacia, but little is known about it. Dacian is usually considered to have been a northern branch of the Thracian language, and, like Thracian, Dacian was a satem language.

About 300 words found only in Romanian or with a cognate in the Albanian language may be inherited from Dacian (for example: barză "stork", balaur "dragon", mal "shore", brânză "cheese").[citation needed] Some of these possibly Dacian words are related to pastoral life (for example, brânză "cheese"). Some linguists and historians have asserted that Albanians are Dacians who were not Romanized and migrated southward.[90]

A different view, which belongs to the "immigrationist theory", is that these non-Latin words with Albanian cognates are not necessarily Dacian, but rather were brought into the territory that is modern Romania by Romance-speaking Aromanian shepherds migrating north from Albania, Serbia, and northern Greece who became the Romanian people.[91]

While most of Romanian grammar and morphology are based on Latin, there are some features that are shared only with other languages of the Balkans and not found in other Romance languages. The shared features of Romanian and the other languages of the Balkan language area (Bulgarian, Macedonian, Albanian, Greek, and Serbo-Croatian) include a suffixed definite article, the syncretism of genitive and dative case and the formation of the future and the alternation of infinitive with subjunctive constructions.[92][93] According to a well-established scholarly theory, most Balkanisms could be traced back to the development of the Balkan Romance languages; these features were adopted by other languages due to language shift.[94]

Slavic influence[]

Slavic influence on Romanian is especially noticeable in its vocabulary, with words of Slavic origin constituting about 10–15% of modern Romanian lexicon,[95][96] and with further influences in its phonetics, morphology and syntax. The greater part of its Slavic vocabulary comes from Old Church Slavonic,[97][98] which was the official written language of Wallachia and Moldavia from the 14th to the 18th century (although not understood by most people), as well as the liturgical language of the Romanian Orthodox Church.[99][100] As a result, much Romanian vocabulary dealing with religion, ritual, and hierarchy is Slavic.[101][99] The number of high-frequency Slavic-derived words is also believed to indicate contact or cohabitation with South Slavic tribes from around the 6th century, though it is disputed where this took place (see Origin of the Romanians).[99] Words borrowed in this way tend to be more vernacular (compare sfârși, "to end", with săvârși, "to commit").[101] The extent of this borrowing is such that some scholars once mistakenly viewed Romanian as a Slavic language.[102][103][104] It has also been argued that Slavic borrowing was a key factor in the development of [ɨ] (î and â) as a separate phoneme.[105]

Other influences[]

Even before the 19th century, Romanian came in contact with several other languages. Some notable examples include:

- German: cartof < Kartoffel "potato", bere < Bier "beer", șurub < Schraube "screw", turn < Turm "tower", ramă < Rahmen "frame", muștiuc < Mundstück "mouth piece", bormașină < Bohrmaschine "drilling machine", cremșnit < Kremschnitte "cream slice", șvaițer < Schweizer "Swiss cheese", șlep < Schleppkahn "barge", șpriț < Spritzer "wine with soda water", abțibild < Abziehbild "decal picture", șnițel < (Wiener) Schnitzel "a battered cutlet", șmecher < Schmecker "taster (not interested in buying)",șuncă < dialectal Schunke (Schinken) "ham", punct < Punkt "point", maistru < Meister "master", rundă < Runde "round".

Furthermore, during the Habsburg and, later on, Austrian rule of Banat, Transylvania, and Bukovina, a large number of words were borrowed from Austrian High German, in particular in fields such as the military, administration, social welfare, economy, etc.[106] Subsequently, German terms have been taken out of science and technics, like: șină < Schiene "rail", știft < Stift "peg", liță < Litze "braid", șindrilă < Schindel "shingle", ștanță < Stanze "punch", șaibă < Scheibe "washer", ștangă < Stange "crossbar", țiglă < Ziegel "tile", șmirghel < Schmirgelpapier "emery paper";

- Greek: folos < ófelos "use", buzunar < buzunára "pocket", proaspăt < prósfatos "fresh", cutie < cution "box", portocale < portokalia "oranges". While Latin borrowed words of Greek origin, Romanian obtained Greek loanwords on its own. Greek entered Romanian through the apoikiai (colonies) and emporia (trade stations) founded in and around Dobruja, through the presence of Byzantine Empire in north of the Danube, through Bulgarian during Bulgarian Empires that converted Romanians to Orthodox Christianity, and after the Greek Civil War, when thousands of Greeks fled Greece.

- Hungarian: a cheltui < költeni "to spend", a făgădui < fogadni "to promise", a mântui < menteni "to save", oraș < város "city";

- Turkish: papuc < pabuç "slipper", ciorbă < çorba "wholemeal soup, sour soup", bacșiș < bahşiş "tip" (ultimately from Persian baksheesh);

- Additionally, the Romani language has provided a series of slang words to Romanian such as: mișto "good, beautiful, cool" < mišto,[107] gagică "girlie, girlfriend" < gadji, a hali "to devour" < halo, mandea "yours truly" < mande, a mangli "to pilfer" < manglo.

French, Italian, and English loanwords[]

Since the 19th century, many literary or learned words were borrowed from the other Romance languages, especially from French and Italian (for example: birou "desk, office", avion "airplane", exploata "exploit"). It was estimated that about 38% of words in Romanian are of French and/or Italian origin (in many cases both languages); and adding this to Romanian's native stock, about 75%–85% of Romanian words can be traced to Latin. The use of these Romanianized French and Italian learned loans has tended to increase at the expense of Slavic loanwords, many of which have become rare or fallen out of use. As second or third languages, French and Italian themselves are better known in Romania than in Romania's neighbors. Along with the switch to the Latin alphabet in Moldova, the re-latinization of the vocabulary has tended to reinforce the Latin character of the language.

In the process of lexical modernization, much of the native Latin stock have acquired doublets from other Romance languages, thus forming a further and more modern and literary lexical layer. Typically, the native word is a noun and the learned loan is an adjective. Some examples of doublets:

| Latin | Native stock | Learned loan |

|---|---|---|

| agilis 'quick’ | ager 'astute’ | agil 'agile' (< French, Italian agile) |

| aqua | apă 'water’ | acvatic 'aquatic' (< Fr aquatique) |

| dens, dentem | dinte 'tooth’ | dentist 'dentist' (< Fr dentiste, It dentista) |

| directus | drept 'straight; right’ | direct 'direct' (< Fr direct) |

| frigidus 'cold' (adj.) | frig 'cold' (noun) | frigid 'frigid' (< Fr frigide) |

| rapidus | repede 'quick’ | rapid 'quick' (< Fr rapide, It rapido) |

In the 20th century, an increasing number of English words have been borrowed (such as: gem < jam; interviu < interview; meci < match; manager < manager; fotbal < football; sandviș < sandwich; bișniță < business; chec < cake; veceu < WC; tramvai < tramway). These words are assigned grammatical gender in Romanian and handled according to Romanian rules; thus "the manager" is managerul. Some borrowings, for example in the computer field, appear to have awkward (perhaps contrived and ludicrous) 'Romanisation,' such as cookie-uri which is the plural of the Internet term cookie.

Lexis[]

A statistical analysis sorting Romanian words by etymological source carried out by Macrea (1961)[97] based on the DLRM[108] (49,649 words) showed the following makeup:[98][unreliable source?]

- 43% recent Romance loans (mainly French: 38.42%, Latin: 2.39%, Italian: 1.72%)

- 20% inherited Latin

- 11.5% Slavic (Old Church Slavonic: 7.98%, Bulgarian: 1.78%, Bulgarian-Serbian: 1.51%)

- 8.31% Unknown/unclear origin

- 3.62% Turkish

- 2.40% Modern Greek

- 2.17% Hungarian

- 1.77% German (including Austrian High German)[106]

- 2.24% Onomatopoeic

If the analysis is restricted to a core vocabulary of 2,500 frequent, semantically rich and productive words, then the Latin inheritance comes first, followed by Romance and classical Latin neologisms, whereas the Slavic borrowings come third.

Romanian has a lexical similarity of 77% with Italian, 75% with French, 74% with Sardinian, 73% with Catalan, 72% with Portuguese and Rheto-Romance, 71% with Spanish.[109]

Although they are rarely used nowadays, the Romanian calendar used to have the traditional Romanian month names, unique to the language.[111]

The longest word in Romanian is pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcaniconioză, with 44 letters,[112] but the longest one admitted by the Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române ("Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language", DEX) is electroglotospectrografie, with 25 letters.[113][114]

Grammar[]

Romanian nouns are characterized by gender (feminine, masculine, and neuter), and declined by number (singular and plural) and case (nominative/accusative, dative/genitive and vocative). The articles, as well as most adjectives and pronouns, agree in gender, number and case with the noun they modify.

Romanian is the only Romance language where definite articles are enclitic: that is, attached to the end of the noun (as in Scandinavian, Bulgarian and Albanian), instead of in front (proclitic).[115] They were formed, as in other Romance languages, from the Latin demonstrative pronouns.

As in all Romance languages, Romanian verbs are highly inflected for person, number, tense, mood, and voice. The usual word order in sentences is subject–verb–object (SVO). Romanian has four verbal conjugations which further split into ten conjugation patterns. Verbs can be put in five moods that are inflected for the person (indicative, conditional/optative, imperative, subjunctive, and presumptive) and four impersonal moods (infinitive, gerund, supine, and participle).

Phonology[]

Romanian has seven vowels: /i/, /ɨ/, /u/, /e/, /ə/, /o/ and /a/. Additionally, /ø/ and /y/ may appear in some borrowed words. Arguably, the diphthongs /e̯a/ and /o̯a/ are also part of the phoneme set. There are twenty-two consonants. The two approximants /j/ and /w/ can appear before or after any vowel, creating a large number of glide-vowel sequences which are, strictly speaking, not diphthongs.

In final positions after consonants, a short /i/ can be deleted, surfacing only as the palatalization of the preceding consonant (e.g., [mʲ]). Similarly, a deleted /u/ may prompt labialization of a preceding consonant, though this has ceased to carry any morphological meaning.

Phonetic changes[]

Owing to its isolation from the other Romance languages, the phonetic evolution of Romanian was quite different, but the language does share a few changes with Italian, such as [kl] → [kj] (Lat. clarus → Rom. chiar, Ital. chiaro, Lat. clamare → Rom. chemare, Ital. chiamare) and [ɡl] → [ɡj] (Lat. *glacia (glacies) → Rom. gheață, Ital. ghiaccia, ghiaccio, Lat. *ungla (ungula) → Rom. unghie, Ital. unghia), although this did not go as far as it did in Italian with other similar clusters (Rom. place, Ital. piace); another similarity with Italian is the change from [ke] or [ki] to [tʃe] or [tʃi] (Lat. pax, pacem → Rom. and Ital. pace, Lat. dulcem → Rom. dulce, Ital. dolce, Lat. circus → Rom. cerc, Ital. circo) and [ɡe] or [ɡi] to [dʒe] or [dʒi] (Lat. gelu → Rom. ger, Ital. gelo, Lat. marginem → Rom. and Ital. margine, Lat. gemere → Rom. geme (gemere), Ital. gemere). There are also a few changes shared with Dalmatian, such as /ɡn/ (probably phonetically [ŋn]) → [mn] (Lat. cognatus → Rom. cumnat, Dalm. comnut) and /ks/ → [ps] in some situations (Lat. coxa → Rom. coapsă, Dalm. copsa).

Among the notable phonetic changes are:

- diphthongization of e and o → ea and oa, before ă (or e as well, in the case of o) in the next syllable:

- Lat. cera → Rom. ceară (wax)

- Lat. sole → Rom. soare (sun)

- iotation [e] → [ie] in the beginning of the word

- Lat. herba → Rom. iarbă (grass, herb)

- velar [k ɡ] → labial [p b m] before alveolar consonants and [w] (e.g. ngu → mb):

- Lat. octo → Rom. opt (eight)

- Lat. lingua → Rom. limbă (tongue, language)

- Lat. signum → Rom. semn (sign)

- Lat. coxa → Rom. coapsă (thigh)

- rhotacism [l] → [r] between vowels

- Lat. caelum → Rom. cer (sky)

- Alveolars [d t] assibilated to [(d)z] [ts] when before short [e] or long [iː]

- Lat. deus → Rom. zeu (god)

- Lat. tenem → Rom. ține (hold)

Romanian has entirely lost Latin /kw/ (qu), turning it either into /p/ (Lat. quattuor → Rom. patru, "four"; cf. It. quattro) or /k/ (Lat. quando → Rom. când, "when"; Lat. quale → Rom. care, "which"). In fact, in modern re-borrowings, while isolated cases of /kw/ exist, as in cuaternar "quaternary", it usually takes the German-like form /kv/, as in acvatic, "aquatic". Notably, it also failed to develop the palatalised sounds /ɲ/ and /ʎ/, which exist at least historically in all other major Romance languages, and even in neighbouring non-Romance languages such as Serbian and Hungarian. However, the other Eastern Romance languages kept these sounds, so it's likely old Romanian had them as well.

Writing system[]

The first written record about a Romance language spoken in the Middle Ages in the Balkans is from 587. A Vlach muleteer accompanying the Byzantine army noticed that the load was falling from one of the animals and shouted to a companion Torna, torna frate (meaning "Return, return brother!"), and, "sculca" (out of bed). Theophanes Confessor recorded it as part of a 6th-century military expedition by and Priscus against the Avars and Slovenes.[116]

The oldest surviving written text in Romanian is a letter from late June 1521,[117] in which Neacșu of Câmpulung wrote to the mayor of Brașov about an imminent attack of the Turks. It was written using the Cyrillic alphabet, like most early Romanian writings. The earliest surviving writing in Latin script was a late 16th-century Transylvanian text which was written with the Hungarian alphabet conventions.

In the 18th century, Transylvanian scholars noted the Latin origin of Romanian and adapted the Latin alphabet to the Romanian language, using some orthographic rules from Italian, recognized as Romanian's closest relative. The Cyrillic alphabet remained in (gradually decreasing) use until 1860, when Romanian writing was first officially regulated.

In the Soviet Republic of Moldova, the Russian-derived Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet was used until 1989, when the Romanian Latin alphabet was introduced; in the breakaway territory of Transnistria the Cyrillic alphabet remains in use.[118]

Romanian alphabet[]

The Romanian alphabet is as follows:

Capital letters A Ă Â B C D E F G H I Î J K L M N O P Q R S Ș T Ț U V W X Y Z Lower case letters a ă â b c d e f g h i î j k l m n o p q r s ș t ț u v w x y z Phonemes /a/ /ə/ /ɨ/ /b/ /k/,

/t͡ʃ//d/ /e/,

/e̯/,

/je//f/ /ɡ/,

/d͡ʒ//h/,

mute/i/,

/j/,

/ʲ//ɨ/ /ʒ/ /k/ /l/ /m/ /n/ /o/,

/o̯//p/ /k/ /r/ /s/ /ʃ/ /t/ /t͡s/ /u/,

/w//v/ /v/,

/w/,

/u//ks/,

/ɡz//j/,

/i//z/

K, Q, W and Y, not part of the native alphabet, were officially introduced in the Romanian alphabet in 1982 and are mostly used to write loanwords like kilogram, quasar, watt, and yoga.

The Romanian alphabet is based on the Latin script with five additional letters Ă, Â, Î, Ș, Ț. Formerly, there were as many as 12 additional letters, but some of them were abolished in subsequent reforms. Also, until the early 20th century, a breve marker was used, which survives only in ă.

Today the Romanian alphabet is largely phonemic. However, the letters â and î both represent the same close central unrounded vowel /ɨ/. Â is used only inside words; î is used at the beginning or the end of non-compound words and in the middle of compound words. Another exception from a completely phonetic writing system is the fact that vowels and their respective semivowels are not distinguished in writing. In dictionaries the distinction is marked by separating the entry word into syllables for words containing a hiatus.

Stressed vowels also are not marked in writing, except very rarely in cases where by misplacing the stress a word might change its meaning and if the meaning is not obvious from the context. For example, trei copíi means "three children" while trei cópii means "three copies".

Pronunciation[]

- h is not silent like in other Romance languages such as Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Catalan and French, but represents the phoneme /h/, except in the digraphs ch /k/ and gh /g/ (see below)

- j represents /ʒ/, as in French, Catalan or Portuguese (the sound spelled with s in the English words "vision, pleasure, treasure").

- There are two letters with a comma below, Ș and Ț, which represent the sounds /ʃ/ and /t͡s/. However, the allographs with a cedilla instead of a comma, Ş and Ţ, became widespread when pre-Unicode and early Unicode character sets did not include the standard form.

- A final orthographical i after a consonant often represents the palatalization of the consonant (e.g., lup /lup/ "wolf" vs. lupi /lupʲ/ "wolves") – it is not pronounced like Italian lupi (which also means "wolves"), and is an example of the Slavic influence on Romanian.

- ă represents the schwa, /ə/.

- î and â both represent the sound /ɨ/. In rapid speech (for example in the name of the country) the â sound may sound similar to a casual listener to the short schwa sound ă (in fact, Aromanian does merge the two, writing them ã) but careful speakers will distinguish the sound. The nearest equivalent is the vowel in the last syllable of the word roses for some English speakers. It is also roughly equivalent to European Portuguese /ɨ/, the Polish y or the Russian ы.

- The letter e generally represents the mid front unrounded vowel [e], somewhat like in the English word set. However, the letter e is pronounced as [je] ([j] sounds like 'y' in 'you') when it is the first letter of any form of the verb a fi "to be", or of a personal pronoun, for instance este /jeste/ "is" and el /jel/ "he".[119][120] This addition of the semivowel /j/ does not occur in more recent loans and their derivatives, such as eră "era", electric "electric" etc. Some words (such as iepure "hare", formerly spelled epure) are now written with the initial i to indicate the semivowel.

- x represents either the phoneme sequence /ks/ as in expresie = expression, or /ɡz/ as in exemplu = example, as in English.

- As in Italian, the letters c and g represent the affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ before i and e, and /k/ and /ɡ/ elsewhere. When /k/ and /ɡ/ are followed by vowels /e/ and /i/ (or their corresponding semivowels or the final /ʲ/) the digraphs ch and gh are used instead of c and g, as shown in the table below. Unlike Italian, however, Romanian uses ce- and ge- to write /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ before a central vowel instead of ci- and gi-.

| Group | Phoneme | Pronunciation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ce, ci | /tʃ/ | ch in chest, cheek | cerc (circle), ceașcă (cup), cercel (earring), cină (dinner), ciocan (hammer) |

| che, chi | /k/ | k in kettle, kiss | cheie (key), chelner (waiter), chioșc (kiosk), chitară (guitar), ureche (ear) |

| ge, gi | /dʒ/ | j in jelly, jigsaw | ger (frost), gimnast (gymnast), gem (jam), girafă (giraffe), geantă (bag) |

| ghe, ghi | /ɡ/ | g in get, give | ghețar (glacier), ghid (guide), ghindă (acorn), ghidon (handle bar), stingher (lonely) |

Punctuation and capitalization[]

Uses of punctuation peculiar to Romanian are:

- The quotation marks use the Polish format in the format „quote «inside» quote”, that is, „. . .” for a normal quotation, and double angle symbols for a quotation inside a quotation.

- Proper quotations which span multiple paragraphs do not start each paragraph with the quotation marks; one single pair of quotation marks is always used, regardless of how many paragraphs are quoted.

- Dialogues are identified with quotation dashes.

- The Oxford comma before "and" is considered incorrect ("red, yellow and blue" is the proper format).

- Punctuation signs which follow a text in parentheses always follow the final bracket.

- In titles, only the first letter of the first word is capitalized, the rest of the title using sentence capitalization (with all its rules: proper names are capitalized as usual, etc.).

- Names of months and days are not capitalized (ianuarie "January", joi "Thursday").

- Adjectives derived from proper names are not capitalized (Germania "Germany", but german "German").

Academy spelling recommendations[]

In 1993, new spelling rules were proposed by the Romanian Academy. In 2000, the Moldovan Academy recommended adopting the same spelling rules,[121] and in 2010 the Academy launched a schedule for the transition to the new rules that was intended to be completed by publications in 2011.[122]

On 17 October 2016, Minister of Education Corina Fusu signed Order No. 872, adopting the revised spelling rules as recommended by the Moldovan Academy of Sciences, coming into force on the day of signing (due to be completed within two school years). From this day, the spelling as used by institutions subordinated to the ministry of education is in line with the Romanian Academy's 1993 recommendation. This order, however, has no application to other government institutions and neither has Law 3462 of 1989 (which provided for the means of transliterating of Cyrillic to Latin) been amended to reflect these changes; thus, these institutions, along with most Moldovans, prefer to use the spelling adopted in 1989 (when the language with Latin script became official).

Examples of Romanian text[]

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

- (Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

The sentence in contemporary Romanian. Words inherited directly from Latin are highlighted:

- Toate ființele umane se nasc libere și egale în demnitate și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu rațiune și conștiință și trebuie să se comporte unele față de altele în spiritul fraternității.

The same sentence, with French and Italian loanwords highlighted instead:

- Toate ființele umane se nasc libere și egale în demnitate și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu rațiune și conștiință și trebuie să se comporte unele față de altele în spiritul fraternității.

The sentence rewritten to exclude French and Italian loanwords. Slavic loanwords are highlighted:

- Toate ființele omenești se nasc slobode și deopotrivă în destoinicie și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu înțelegere și cuget și trebuie să se poarte unele față de altele în duh de frățietate.

The sentence rewritten to exclude all loanwords. The meaning is somewhat compromised due to the paucity of native vocabulary:

- Toate ființele omenești se nasc nesupuse și asemenea în prețuire și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu înțelegere și cuget și se cuvine să se poarte unele față de altele după firea frăției.

See also[]

- Albanian–Romanian linguistic relationship

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- Romanian lexis

- Romanianization

- Moldovan language

- BABEL Speech Corpus

- Moldova–Romania relations

Notes[]

- ^ The constitution of the Republic of Moldova refers to the country's language as Moldovan, whilst the 1991 Declaration of Independence names the official language Romanian. In December 2013 a decision of the Constitutional Court of Moldova ruled that the Declaration of Independence takes precedence over the Constitution and that the state language is therefore Romanian, not "Moldovan". "Moldovan court rules official language is 'Romanian,' replacing Soviet-flavored 'Moldovan'"

References[]

- ^ Romanian at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ^ "Româna" [Romania]. Union Latine (in Romanian).

- ^ "Romanian Language". Effective Language Learning.

- ^ "Romanian". MustGo.com.

- ^ The Latin Union reports 28 million speakers for Romanian, out of whom 24 million are native speakers of the language: Latin Union – The odyssey of languages: ro, es, fr, it, pt; see also Ethnologue report for Romanian

- ^ Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People. Microsoft Encarta 2006. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ^ Petit Futé: Roumanie. Editions/Ausgabe 2004–2005, ISBN 2-7469-1132-9, S. 37.

- ^ "Istoria limbii române" ("History of the Romanian Language"), II, Academia Română, Bucharest, 1969

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Petrucci 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Andreose & Renzi 2013, pp. 285–287.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Andreose & Renzi 2013, p. 287.

- ^ Ștefan Pascu, Documente străine despre români, ed. Arhivelor statului, București 1992, ISBN 973-95711-2-3

- ^ Gerhard Ernst; Martin-Dietrich Gleßgen; Christian Schmitt; Wolfgang Schweickard (2008). Romanische Sprachgeschichte / Histoire linguistique de la Romania. 1. Teilband. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 738–. ISBN 978-3-11-019412-8.

- ^ Mircea Tomescu (1968). Istoria cărții românești de la începuturi până la 1918. Editura Științifică București. p. 40.

- ^ Tranquillo Andronico în Endre Veress, Fontes rerum transylvanicarum: Erdélyi történelmi források, Történettudományi Intézet, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, Budapest, 1914, S. 204

- ^ "...si dimandano in lingua loro Romei...se alcuno dimanda se sano parlare in la lingua valacca, dicono a questo in questo modo: Sti Rominest ? Che vol dire: Sai tu Romano ?..." în: Claudiu Isopescu, Notizie intorno ai romeni nella letteratura geografica italiana del Cinquecento, în Bulletin de la Section Historique, XVI, 1929, p. 1- 90

- ^ "Ex Vlachi Valachi, Romanenses Italiani,/Quorum reliquae Romanensi lingua utuntur.../Solo Romanos nomine, sine re, repraesentantes./Ideirco vulgariter Romuini sunt appelanti", Ioannes Lebelius, De opido Thalmus, Carmen Istoricum, Cibinii, 1779, p. 11 – 12

- ^ "qui eorum lingua Romini ab Romanis, nostra Walachi, ab Italis appellantur" St. Orichovius, Annales polonici ab excessu Sigismundi, in I. Dlugossus, Historiae polonicae libri XII, col 1555

- ^ "...Valacchi, qui se Romanos nominant..." "Gens quae ear terras (Transsylvaniam, Moldaviam et Transalpinam) nostra aetate incolit, Valacchi sunt, eaque a Romania ducit originem, tametsi nomine longe alieno..." De situ Transsylvaniae, Moldaviae et Transaplinae, in Monumenta Hungariae Historica, Scriptores; II, Pesta, 1857, p. 120

- ^ "Tout ce pays: la Wallachie, la Moldavie et la plus part de la Transylvanie, a esté peuplé des colonies romaines du temps de Trajan l'empereur… Ceux du pays se disent vrais successeurs des Romains et nomment leur parler romanechte, c'est-à-dire romain ... " în Voyage fait par moy, Pierre Lescalopier l’an 1574 de Venise a Constantinople, în: Paul Cernovodeanu, Studii și materiale de istorie medievală, IV, 1960, p. 444

- ^ "Anzi essi si chiamano romanesci, e vogliono molti che erano mandati quì quei che erano dannati a cavar metalli..." în: Maria Holban, Călători străini despre Țările Române, București, Editura Stiințifică, 1970, vol. II, pp. 158–161

- ^ Palia de la Orăștie (1581–1582), Bucuresti, 1968

- ^ Grigore Ureche, Letopisețul Țării Moldovei, pp. 133–134

- ^ Constantiniu, Florin, O istorie sinceră a poporului român (An honest history of the Romanian people), Univers Enciclopedic, București, 1997, ISBN 97-3924-307-X, p. 175

- ^ "Valachos...dicunt enim communi modo loquendi: Sie noi sentem Rumeni: etiam nos sumus Romani. Item: Noi sentem di sange Rumena: Nos sumus de sanguine Romano" Martinus Szent-Ivany, Dissertatio Paralimpomenica rerum memorabilium Hungariae, Tyrnaviae, 1699, p. 39

- ^ From Descriptio Moldaviae: "Valachiae et Transylvaniae incolis eadem est cum Moldavis lingua, pronunciatio tamen rudior, ut dziur, Vlachus proferet zur, jur, per z polonicum sive j gallicum; Dumnedzeu, Deus, val. Dumnezeu: akmu, nunc, val. akuma, aczela hic, val: ahela."

- ^ Eugen Munteanu. Dinamica istorică a cultivării instituţionalizate a limbii române, în "Revista română", Iași, anul IV, nr. 4 (34), decembrie 2003, p. 6 (I), nr. 1 (35), martie 2004, p. 7 (II); nr. 2, iunie 2004, p. 6 (III); nr. 3, octombrie 2004, p. 6 (IV); nr. 4 (38), decembrie 2004, p. 6 (V). Retrieved 11 May 2016 from https://www.academia.edu/12163793/Dinamica_istoric%C4%83_a_cultiv%C4%83rii_institu%C5%A3ionalizate_a_limbii_rom%C3%A2ne_%C3%AEn_Revista_rom%C3%A2n%C4%83_Ia%C5%9Fi_anul_IV_nr._4_34_decembrie_2003_p._6_I_nr._1_35_martie_2004_p._7_II_nr._2_iunie_2004_p._6_III_nr._3_octombrie_2004_p._6_IV_nr._4_38_decembrie_2004_p._6_V_ .

- ^ Jump up to: a b Micu, Samuil; Șincai, Gheorghe (1780). Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae (in Latin). Vienna.

- ^ (in Russian)Charter for the organization of the Bessarabian Oblast, 29 April 1818, in "Печатается по изданию: Полное собрание законов Российской империи. Собрание первое.", Vol 35. 1818, Sankt Petersburg, 1830, pg. 222–227. Available online at hrono.info

- ^ King, Charles (2000). The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 08-1799-792-X.

- ^ D’hulst, Yves; Coene, Martine; Avram, Larisa (2004). "Syncretic and Analytic Tenses in Romanian: The Balkan Setting of Romance". In Mišeska Tomić, Olga (ed.). Balkan Syntax and Semantics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 366. doi:10.1075/la.67.18dhu. ISBN 978-90-272-2790-4.

In its evolution, Romanian simplified the original Latin tense system in extreme ways.

- ^ D’hulst, Yves; Coene, Martine; Avram, Larisa (2004). "Syncretic and Analytic Tenses in Romanian: The Balkan Setting of Romance". In Mišeska Tomić, Olga (ed.). Balkan Syntax and Semantics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 355. doi:10.1075/la.67.18dhu. ISBN 978-90-272-2790-4.

general absence of consecutio temporum.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Hungarian Census 2011" (PDF).

- ^ Ethnologue.com

- ^ "Bilancio demografico nazionale". www.istat.it. 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Ausländische Bevölkerung - Statistisches Bundesamt" (in German). destatis.de. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, comunidades, Sexo y Año. Datos provisionales 2020". INE.

- ^ "Table 1.3: Overseas-born population in the United Kingdom, excluding some residents in communal establishments, by sex, by country of birth, January 2019 to December 2019". Office for National Statistics. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020. Figure given is the central estimate. See the source for 95% confidence intervals.

- ^ "Franta" [France]. Departamentul pentru Romanii de Pretutindeni (in Romanian). 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012.

- ^ non-profit Data [2].

- ^ "Austria". Departamentul pentru Romanii de Pretutindeni (in Romanian). 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012.

- ^ General Secretariat of National Statistical Service of Greece [3].

- ^ Portugal foreigners. [4].

- ^ Cyprus 2011 census [5].

- ^ Irish 2011 census [6].

- ^ "TĂRILE NORDICE « DRP – Departamentul pentru Romanii de Pretutindeni". Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ 2010 Russia Census Archived 4 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Perepis 2010

- ^ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. "Redirect to Census data page". www.abs.gov.au.

- ^ RDSCJ.ro Archived 22 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Latin Union – Languages and cultures online 2005". Dtil.unilat.org. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

- ^ According to the 1993 Statistical Abstract of Israel there were 250,000 Romanian speakers in Israel, of a population of 5,548,523 in 1995 (census).

- ^ "Reports of about 300,000 Jews that left the country after WW2". Eurojewcong.org. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Evenimentul Zilei". Evz.ro. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Constitution of Romania". Cdep.ro. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Legea "Pruteanu": 500/2004 – Law on the Protection of the Romanian Language

- ^ Art. 27 (3), Legea nr. 26/1990 privind Registrul Comerțului

- ^ "Ministry of Education of Romania". Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2006.

- ^ "31 august - Ziua Limbii Române". Agerpres (in Romanian). 31 August 2020.

- ^ "De ce este sărbătorită Ziua Limbii Române la 31 august". Historia (in Romanian). 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Declarația de independența a Republicii Moldova, Moldova Suverană" (in Romanian). Moldova-suverana.md. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "A Field Guide to the Main Languages of Europe – Spot that language and how to tell them apart" (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Moldovan Court Rules Official Language is 'Romanian,' Replacing Soviet-Flavored 'Moldovan'". Fox News. Associated Press. 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Marian Lupu: Româna și moldoveneasca sunt aceeași limbă". Realitatea .NET. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of Languages. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 518. ISBN 07-4753-117-X.

- ^ Legea cu privire la functionarea limbilor vorbite pe teritoriul RSS Moldovenesti Nr.3465-XI din 01.09.89 Vestile nr.9/217, 1989 Archived 19 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine (Law regarding the usage of languages spoken on the territory of the Republic of Moldova): "Moldavian RSS supports the desire of the Moldavian that live across the borders of the Republic, and – considering the existing Moldo-Romanian linguistic identity – of the Romanians that live on the territory of the USSR, of doing their studies and satisfying their cultural needs in their maternal language."

- ^ National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova: Census 2014

- ^ Biroul Național de Statistică, acuzat că a falsificat rezultatele recensământului, Independent, 29 March 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Official Gazette of Republic of Serbia, No.1/90

- ^ Article 24, The Statute Of The Autonomous Province Of Vojvodina, published in the Official Gazette of AP Vojvodina No.20/2014

- ^ "Official use of languages and scripts in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina" published by the Provincial Secretariat for Regulations, Administration and National Minorities

- ^ Provincial Secretariat for Regulations, Administration and National Minorities: "Official use of the Romanian language in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (APV)"

- ^ Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Internetový časopis človek a spoločnosť". www.clovekaspolocnost.sk. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009.

- ^ Kramar Andriy. "University of Chernivtsi". Chnu.cv.ua. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Cursuri de perfecționare" Archived 25 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Ziua, 19 August 2005

- ^ "Data concerning the teaching of the Romanian language abroad" Archived 7 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Romanian Language Institute.

- ^ "Romanian language", in Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Delyusto, Maryna (2016). "Mul'tilingval'nyy atlas mezhdurech'ya Dnestra i Dunaya: Istochniki i priyemy sozdaniya" Мультилингвальный атлас междуречья Днестра и Дуная:источники и приемы создания [Multi-Lingual Atlas of Dialects Spread Between the Danube and the Dniester Rivers: Sources and Tools of Creation]. Journal of Danubian Studies and Research (in Russian). 6 (1): 362–369.

- ^ Arjocu, Florin (29 June 2020). "Satul din România unde se vorbește o limbă secretă. Tălăuzeşti gumuțeasca?". Știri România (in Romanian).

- ^ Florea, Sorin (1 June 2020). "Care este satul din România unde se vorbește o limbă secretă?". Shtiu (in Romanian).

- ^ "În localitatea Totoi, județul Alba, se vorbește o limbă specifică locului". Realitatea TV (in Romanian). 19 January 2009.

- ^ Arsenie, Dan (9 December 2011). "Totoiana – messengerul de pe uliță. Povestea unei limbi inventate de români". GreatNews.ro (in Romanian).

- ^ ""Limba intoarsă" vorbită în Totoi". Ziare.com (in Romanian). 2 November 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. p. 50.

- ^ Pei, Mario (1949). Story of Language. ISBN 03-9700-400-1.

- ^ Ethnologue, Romanian

- ^ Sandiuc, Corina (1 November 2014). "Languages and cultures in contact: The French language and the maritime terminology". Diversitate Si Identitate Culturala in Europa. 11 (2). ISSN 2067-0931.

- ^ Vladimir Georgiev (Gheorghiev), (in Romanian) Raporturile dintre limbile dacă, tracă și frigiană, "Studii Clasice" Journal, II, 1960, 39–58

- ^ Schramm, Gottfried (1997). Ein Damn bricht. Die römische Donaugrenze und die Invasionen des 5–7. Jahrhunderts in Lichte der Namen und Wörter.

- ^ Mišeska Tomić, Olga (2006). Balkan Sprachbund Morpho-Syntactic Features. Springer. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4020-4487-8.

- ^ Schulte, Kim (2009). "Loanwords in Romanian". In Haspelmath, Martin; Tadmor, Uri (eds.). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 230–259. ISBN 978-3-11-021843-5.

- ^ Lindstedt, J. (2000). "Linguistic Balkanization: Contact-induced change by mutual reinforcement". In D. G. Gilbers; et al. (eds.). Languages in Contact. Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics, 28. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA: Rodopi. p. 235. ISBN 90-4201-322-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marius Sala (coord), Mihaela Bîrlădeanu, Maria Iliescu, Liliana Macarie, Ioana Nichita, Mariana Ploae-Hanganu, Maria Theban, Ioana Vintilă-Rădulescu, Vocabularul reprezentativ al limbilor romanice (VRLR) (Bucharest: Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică, 1988).

- ^ Schulte, Kim. "Loanwords in Romanian". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)[dead link], published in Martin Haspelmath; Uri Tadmor (22 December 2009). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. p. 243. ISBN 978-3-11-021844-2. - ^ Jump up to: a b Macrea, Dimitrie (1961). "Originea și structura limbii româneb (7–45)". Probleme de lingvistică română (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Științifică. p. 32.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela, ed. (2013). The Grammar of Romanian (First ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780199644926.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Keith Hitchins (20 February 2014). A Concise History of Romania. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-87238-6.

- ^ Virginia Hill; Gabriela Alboiu (2016). Verb Movement and Clause Structure in Old Romanian. Oxford University Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-19-873650-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bernard Comrie (13 January 2009). The World's Major Languages. Routledge. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-134-26156-7.

- ^ Millar, Robert McColl; Trask, Larry (2015). Trask's Historical Linguistics. Routledge. p. 292. ISBN 9781317541776.

The Romance language Romanian has borrowed so many Slavonic words that scholars for a while believed it was a Slavonic language."

- ^ Boia, Lucian (2001). Romania: Borderland of Europe. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781861891037.

- ^ Еmil Fischer (1904). Die Herkunft Der Rumanen: Eine Historisch-Linguistisch-Etnographische Studie. Handels-Druckerei. p. 132–3.

- ^ Margaret E. L. Renwick (2014). The Phonetics and Phonology of Contrast: The Case of the Romanian Vowel System. De Gruyter. pp. 44–5. ISBN 978-3-11-036277-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hans Dama, "Lexikale Einflüsse im Rumänischen aus dem österreichischen Deutsch" ("Lexical influences of 'Austrian'-German on the Romanian Language") Archived 18 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ Zafiu, Rodica (2009). "Mișto și legenda bastonului". România literară. No. 6. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

There is no doubt among linguists about the Romany etymology of the Romanian word mișto, but a fairly widespread folk etymology and urban legend maintains that the German phrase mit Stock 'with stick' would be its true origin.

- ^ Macrea, Dimitrie, ed. (1958). Dictionarul limbii române moderne (in Romanian). Bucharest: Academia Română. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Romanian". Ethnologue.

- ^ Vocabularul reprezentativ diferă de vocabularul fundamental (VF) și de fondul principal lexical (FP). Cf. SCL (Studii și cercetări lingvistice), an XXVII (1976), nr. 1, p. 61-66 și SCL (1974) nr. 3, p. 247. Cf. Theodor Hristea, "Structura generală a lexicului românesc", Sinteze de limba română, eds., Theodor Hristea (coord.), Mioara Avram, Grigore Brâncuș, Gheorghe Bulgăr, Georgeta Ciompec, Ion Diaconescu, Rodica Bogza-Irimie & Flora Șuteu (Bucharest: 1984), 13.

- ^ *Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române, Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică "Iorgu Iordan", Editura Univers Enciclopedic, 1998

- ^ Bălhuc, Paul (15 January 2017). "Câte litere are cel mai lung cuvânt din limba română și care este singurul termen ce conține toate vocalele". Adevărul (in Romanian).

- ^ "Electroglotospectrografie". Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române (in Romanian). Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Curiozități lingvistice: cele mai lungi cuvinte din limba română". Dicție.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Săvescu, Oana (2012). "When Syncretism Meets Word Order. On Clitic Order in Romanian". Probus. 24 (2): 233–256. doi:10.1515/probus-2012-0010.

- ^ Baynes, Thomas Spencer, ed. (1898). Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature. XXIV (9th ed.). Edinburgh: A. and C. Black. p. 269 https://books.google.com/books?id=Zt5TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA269. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Sarlin, Mika (2014). Romanian Grammar (2nd ed.). Helsinki: Books on Demand. p. 15. ISBN 9789522868985.

- ^ Dyer, Donald L. (1999). "Some Influences of Russian on the Romanian of Moldova during the Soviet Period". The Slavic and East European Journal. 43 (1): 85–98. doi:10.2307/309907. JSTOR 309907.

- ^ (in Romanian) Several Romanian dictionaries specify the pronunciation [je] for word-initial letter e in some personal pronouns: el, ei, etc. and in some forms of the verb a fi (to be): este, eram, etc.

- ^ (in Romanian) Mioara Avram, Ortografie pentru toți, Editura Litera, Chișinău, 1997, p. 29

- ^ The new edition of "Dicționarul ortografic al limbii române (ortoepic, morfologic, cu norme de punctuație)" – introduced by the Academy of Sciences of Moldova and recommended for publishing following a conference on 15 November 2000 – applies the decision of the General Meeting of the Romanian Academy from 17 February 1993, regarding the reintroduction to "â" and "sunt" in the orthography of the Romanian language. (Introduction, Institute of Linguistics of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova)

- ^ "Gheorghe Duca: Trebuie schimbată atitudinea de sorginte proletară față de savanți și în genere față de intelectuali" (in Romanian). Allmoldova. 4 June 2010. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

Bibliography[]

- Andreose, Alvise; Renzi, Lorenzo (2013). "Geography and distribution of the Romance languages in Europe". In Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages, Volume II: Contexts. Cambridge University Press. pp. 283–334. ISBN 978-0-521-80073-0.

- Giurescu, Constantin, The Making of the Romanian People and Language, Bucharest, 1972.

- Kahl, Thede (ed.), Das Rumänische und seine Nachbarn, Berlin, 2009.

- Paliga, Sorin, The Earliest Slavic Borrowings in Romanian, Romanoslavica vol. XLVI, nr. 4, Editura Universității din București, Bucharest, 2010.

- Petrucci, Peter R. (1999). Slavic Features in the History of Rumanian. LINCOM Europa. ISBN 38-9586-599-0.

- Rosetti, Alexandru, Istoria limbii române, 2 vols., Bucharest, 1965–1969.

- Uwe, Hinrichs (ed.), Handbuch der Südosteuropa-Linguistik, Wiesbaden, 1999.

Further reading[]

- Paliga, Sorin (2010). "When Could Be Dated the 'Earliest Slavic Borrowings in Romanian'?" (PDF). Romanoslavica. 46 (4): 101–119.

External links[]

| Romanian edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Romanian language

- Languages of Austria

- Languages of Hungary

- Languages of Kazakhstan

- Languages of Moldova

- Languages of Romania

- Languages of Russia

- Languages of Serbia

- Languages of Transnistria

- Languages of Ukraine

- Languages of Vojvodina