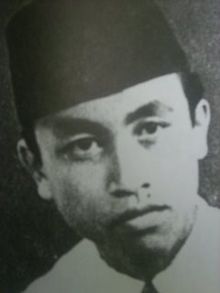

Rosli Dhobi

Rosli Dhobi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 March 1932 Kampung Pulo, Sibu, Sarawak |

| Died | 2 March 1950 (aged 17) |

| Burial place | Kuching Central Prison Cemetery, Kuching (1950-1996) Masjid An-Nur, Sibu (present location) |

Rosli Dhobi (18 March 1932 – 2 March 1950) was a Malay Sarawakian nationalist from Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia during the British crown colony era in that state.

He was a member leader of the Rukun 13, an active organisation in the Anti-cession movement of Sarawak, along with Morshidi Sidek, Awang Rambli Bin Deli and . It was a secret cell organisation, composed of nationalists, which carried out assassinations of officers of the British Colonial government in Sarawak. He was well known for his assassination of Duncan George Stewart, the second governor of colonial Sarawak, in 1949.

Early life[]

Rosli Dhobi was born on 18 March 1932 at No. 94, Kampung Pulo, Sibu, Sarawak as the second child in the washerman family.[1] His father, Dhobi bin Buang originated from Indonesia and was a descendant of Raden.[1] His mother, Habibah binti Haji Lamit came from a Sambas family and settled for a long time in Mukah.[1] Little is known about his earlier life although friends regard Rosli as an approachable person despite his quietness.[1] He had an elder sister and a younger brother: Fatimah (born 1928) and Ainie (born 1933).[1]

Rosli started his career as a teacher and quit his job in 1947 to teach in Sibu People's School. Before that, he worked at the Sarawak Public Works Department (PWD)[1] and for Utusan Sarawak. Rosli was known to be a nationalist and a poet. Using the nickname Lidros,[citation needed] Rosli penned down a nationalistic poem titled 'Panggilan Mu yang Suchi' (Malay: "Your Divine Call")[2] which was published in Utusan Sarawak on 28 February 1948. The usage of nicknames was prevalent at the time since the vigorously monitored any attempts to spread words against them. He joined the Sibu Malay Youth Movement (Malay: Pergerakan Pemuda Melayu Sibu) under the leadership of Sirat Haji Yaman.

Rosli joined Rukun 13 in August 1948. He was introduced to the organisation by an old friend, Awang Rambli.

Although one of the Rukun 13's aim was to establish a union of Sarawak with newly independent Indonesia,[3] Tahar Johnny, a cousin of Rosli, denied that Rosli was pro-Indonesia, despite the latter great likings of anything Indonesian and other members of Rukun 13 may have been pro-Indonesia.[4]

Assassination of Duncan George Stewart[]

Background[]

The end of the Second World War had brought an end to the Brooke Dynasty rule in Sarawak; believing it to be in the best interest of the people of Sarawak, Rajah Vyner Brooke ceded the state to the British Crown.[5] Sarawak became a Crown Colony, ruled from the Colonial Office in London, which in turn dispatched a Governor for Sarawak.

This move was opposed by Rajah Muda Anthony Brooke, who was supposed to become the next Rajah Brooke, as well as many native Sarawakians who were initially told that they would be allowed self-government. Anthony Brooke became the leader of the anti-cession movement.

Events[]

On 3 December 1949,[6] Duncan George Stewart, the aforementioned appointed governor of Sarawak, was murdered by the Rukun 13 members, Rosli Dhoby, Awang Ramli Amit Mohd Deli, and in Sibu.[4]

Rosli Dhoby and were among the crowd that welcomed the governor on his arrival to Sibu. After inspecting an honour guard the governor was meeting a group of local school children in near proximity of Rosli. Morshidi began to pretend to take pictures of the governor with a broken camera. The governor stopped to allow Morshidi to photograph him. At that moment, Rosli stabbed the governor.[3]

Rosli was arrested on the spot and sent to Kuching for trial and later into imprisonment. Despite suffering a deep stab wound Stewart is reported to have tried to carry on until blood began to seep through his white uniform.[3] The governor was flown back to Kuching for treatment and later to Singapore, where he died a week after the incident.[3]

Death[]

After a few months languishing in prison, Rosli Dhoby, Awang Ramli Amit Mohd Deli, Morshidi Sidek and Bujang Suntong were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death on 4 December 1949. This move was criticised by many, as Rosli Dhobi was a juvenile at the time of assassination.

Rosli Dhoby was sent to the gallows on the morning of 2 March 1950. Fearing the resentment of the local population, the British government did not allow Rosli Dhoby's body to leave the Kuching Central Prison. Instead, his body was interred in an unmarked tomb within the prison compound.[7]

After Sarawak gained independence on 22 July 1963 from Britain and later through the formation of the Federation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963, a tombstone was put in place at his tomb. The tombstone is now on display at the outer compound of Sarawak Islamic Museum in Kuching after the reinterment of his remains in 1996.[7]

Aftermath[]

Sarawak was sent into tumultuous years, and the anti-Cessionists rebellion were crushed as the support by the locals dwindled due to the "aggressive" tactic used by Rosli Dhoby, alongside the oppositions from some of the Malay leaders who were pro-British. Most of the anti-Cessionists were arrested and later sent into prison, and some of them were even imprisoned in Changi Prison in Singapore.

However, things later returned to normal and peace was restored during the era of 3rd Governor of Sarawak, Sir Anthony Foster Abell. Even those who were imprisoned at Changi were allowed to return to Sarawak, to continue their sentence at Kuching Central Prison.

After 46 years resting in prison compound, the remains of Rosli Dhoby were moved out of the Kuching Central Prison to be buried in the Sarawak's Heroes Mausoleum near An Nur Mosque at his home town of Sibu on 2 March 1996. He was given a state funeral by the Sarawak government.[6]

In 1975, Dr Mahathir Mohamad, minister of education at that time, changed the name of SMK Bandar Sibu into SMK Rosli Dhoby to commemorate the sacrifices of Rosli Dhoby.[8]

In 2009, a miniseries spanning the period from him joining the Rukun 13 up to his death sentence was produced by Malaysian production studio KL Motion Picture Co. titled Warkah Terakhir ("The Final Letter"), with actor Beto Kusyairy portraying Rosli.[citation needed] However, Rosli Dhoby heir Lucas Johnny claimed that the series contained several factual errors. For example, the miniseries portrayed Rosli Dhoby as trying to run away after stabbing the governor. In reality, Rosli was trying to stab the governor the second time but was stopped by the governor's bodyguards.[9]

In 2013, Jeniri Amir, a professor from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS) specialised in political communication, wrote a book about Rosli Dhoby which included much new information.[10] However, according to a book review written by Nordi Achie, another professor from Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) Jeniri's book contained errors with only superficial analysis of newly found information regarding Rosli Dhoby.[11]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Amir, Jeniri. "Rosli Dhoby: Merdeka dengan darah (Rosli Dhoby: Independence through blood)". Sarawak Voice. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Abg Mohd Nizam, Abg Nasser (15 July 2016). "Pemberontakan Rosli Dhoby Terhadap Penjajah Inggeris di Sibu Sarawak (Rebellion of Rosli Dhoby against English Colonisers in Sibu Sarawak)". Faculty of Culture and Humanity - Sunan Ampel State Islamic University Surabaya. Retrieved 5 July 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d Thomson, Mike (14 March 2012). "The stabbed governor of Sarawak". BBC news. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Winston, Way (16 September 2013). "'They lied, Rosli Dhoby not pro-Indonesia'". Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Reece, RHW; Reece, Bob (1982). The Name of Brooke: The End of White Rajah Rule in Sarawak. University of Michigan: Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780195804744. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ian, Stewart (4 March 1996). "Sarawak honours governor's killers". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amir, Jeniri (2 March 2021). "The execution of Rosli Dhoby retold". New Sarawak Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Adawiyah, Rabi Atul (11 September 2014). "Jiwai semangat Rosli Dhoby (Emulate the spirit of Rosli Dhoby)". Harian Metro. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Waris kecewa drama Rosli Dhoby salah fakta (Heir was disappointed because Rosli drama is factually inaccurate)". Malaysiakini. 10 September 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Jeniri, Amir (2013). Rosli Dhoby: merdeka dengan darah (Rosli Dhoby: Independence through blood). Sarawak, Malaysia: Jenza Enterprise. p. 272. ISBN 9789834337568. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Nordie, Achie (2013). "Analisis Kritis dalam pensejarahan ilmiah - satu penyelitian terhadap "Rosli Dhoby - Merdeka dengan darah" (Critical analysis in scientific historiography - research on "Rosli Dhoby - Independence through blood"" (PDF). Retrieved 8 April 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Sources[]

- Adapted from Sabah dan Sarawak Menjadi Tanah Jajahan British, Sejarah Tingkatan 3 textbook

- Adapted from Pembinaan Negara Dan Bangsa Malaysia, Sejarah Tingkatan 5 textbook ISBN 978-983-62-7883-8

See also[]

- Anti-cession movement of Sarawak

- Rentap, an Iban warrior who fought against Brooke

- James W.W. Birch, first Perak resident who was killed by Dato Maharajalela Lela

- 1932 births

- 1950 deaths

- People from Sarawak

- History of Sarawak

- Melanau people

- Malaysian rebels

- Executed Malaysian people

- People executed by British Sarawak by hanging

- Malaysian people convicted of murder

- Malaysian assassins

- 20th-century executions by the United Kingdom

- Executed assassins

- Assassins of heads of government

- People of British Borneo