Rothbury

| Rothbury | |

|---|---|

Rothbury town centre | |

Looking east along Town Foot | |

Rothbury Location within Northumberland | |

| Population | 2,107 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | NU056017 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MORPETH |

| Postcode district | NE65 |

| Dialling code | 01669 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Northumberland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament |

|

Rothbury is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, on the River Coquet, 13.5 miles (21.7 km) northwest of Morpeth and 26 miles (42 km) of Newcastle upon Tyne. At the 2001 Census, it had a population of 2,107.[1]

Rothbury emerged as an important town because of its situation at a crossroads over a ford on the River Coquet. Turnpike roads leading to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Alnwick, Hexham and Morpeth allowed for an influx of families and the enlargement of the settlement in the Middle Ages. Rothbury was chartered as a market town in 1291, and became a centre for dealing in cattle and wool for the surrounding villages in the Early Modern Period.

Today, the town is used as a staging point for recreational walking. Points of interest around Rothbury include the Victorian mansion Cragside, the Simonside Hills and Northumberland National Park.

History[]

Prehistory and Ancient (Pre 500)[]

The area around Rothbury was populated during the prehistoric period, as evidenced by finds dating from the Mesolithic period and later, although all the known finds are from beyond the outer edges of the modern town.[2] Sites include a cairnfield, standing stone and cup-marked rock on Debdon Moor to the north of the town, a well-preserved circular cairn some 26 feet (8 m) in diameter,[3] a late Neolithic or Bronze Age standing stone,[3] and an extensive hillfort, covering an area 165 by 125 metres (541 by 410 ft) and associated cairnfield to the west of the town.[4] No evidence of the Roman period has been found, probably because the town was a considerable distance north beyond Hadrian's Wall.[5]

Saxons (500 -1066)[]

Fragments from an Anglo-Saxon cross, possibly dating from the 9th century, are the only surviving relics pre-dating the Norman conquest. They were discovered in 1849, when part of the church was demolished, and in 1856. They are now in the town church and the University of Newcastle Museum.[2]

Medieval (1066–1465)[]

The first documentary mention of Rothbury, according to a local history,[6] was in around the year 1100, as Routhebiria, or "Routha's town" ("Hrotha", according to Beckensall).[7] The village was retained as a Crown possession after the conquest,[2] but in 1201 King John signed the Rothbury Town Charter and visited Rothbury four years later,[8] when the rights and privileges of the manor of Rothbury were given to Robert Fitz Roger, the baron of Warkworth.[2] Edward I visited the town in 1291, when Fitz Roger obtained a charter to authorise the holding of a market every Thursday, and a three-day annual fair near St Matthew's Day, celebrated on 21 September.[6]

Rothbury was not particularly significant at the time, with records from 1310 showing that it consisted of a house, a garden, a bakehouse and a watermill, all of which were leased to tenants. When the line of Fitz Roger died out, the village reverted to being a crown possession, but in 1334 Edward III gave it to Henry de Percy, who had been given the castle and baronry of Warkworth six years earlier. Despite the Scottish border wars, the village rose in prosperity during the 14th century, and had become the village with the highest parochial value in Northumberland by 1535. Feuds still dominated local affairs, resulting in some parishioners failing to attend church because of them in the 16th century, and at other times, gathering in armed groups in separate parts of the building.[2]

Rothbury became a relatively important village in Coquetdale, being a crossroads situated on a ford of the River Coquet, with turnpike roads leading to Newcastle upon Tyne, Alnwick, Hexham and Morpeth. After it was chartered as a market town in 1291, it became a centre for dealing in cattle and wool for the surrounding villages. A market cross was erected in 1722, but demolished in 1827. In the 1760s, according to Bishop Pococke, the village also had a small craft industry, including hatters. At that time, the village's vicarage and living was in the gift of the Bishop of Carlisle, and worth £500 per year.[8]

Tudors and Stuarts (1465–1714)[]

Bernard Gilpin and the Border Rievers[]

Rothbury has had a turbulent and bloody history. In the 15th and 16th centuries the Coquet valley was a pillaging ground for bands of Reivers who attacked and burned the town with terrifying frequency. Hill farming has been a mainstay of the local economy for many generations. Names such as Armstrong, Charleton and Robson remain well represented in the farming community. Their forebears, members of the reiver 'clans', were in constant conflict with their Scots counterpart. The many fortified farms, known as bastle houses, are reminders of troubled times which lasted until the unification of the kingdoms of England and Scotland in 1603.

The theologian Bernard Gilpin, known as the 'Apostle of the North' for his work in northern England during this period, visited Rothbury. While he preached a sermon, two rival gangs were threatening each other; realising they might start fighting, Gilpin stood between them asking them to reconcile - they agreed as long as Gilpin stayed in their presence. On another occasion, Gilpin observed a glove hanging in the church and asked the sexton about it. He was told it was a challenge to anyone who removed it. Gilpin thus took the glove and put it in his pocket and carried on with his sermon, and no-one challenged him.[8][9][6] A painting of this incident by artist William Bell Scott is housed at Wallington Hall.

Georgians (1714–1837)[]

Near the town's All Saints' Parish Church stands the doorway and site of the 17th-century Three Half Moons Inn, where the Jacobite rebel James Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater stayed with his followers in 1715 prior to marching into a heavy defeat at the Battle of Preston in 1715.[8]

On 16 June 1782, Methodist theologian John Wesley preached in Rothbury.[8]

Victorians (1837–1901)[]

Cragside[]

Although Rothbury is of ancient origin, it mainly developed during the Victorian era. A factor in this development was industrialist Sir William Armstrong, later Lord Armstrong of Cragside, who built the country house, and "shooting box" (hunting lodge), of Cragside, between 1862 and 1865, then extended it as a "fairy palace" between 1869 and 1900. The house and its estate are now in the possession of the National Trust and are open to the public.

1884 royal visit[]

Another factor in Rothbury's Victorian development was the arrival of the railway. Rothbury Station opened in 1870, bringing tourists on walking holidays to the surrounding hill country. This railway was most notably used by the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) and Princess Alexandra and their children (Albert Victor, 10, George later George V, 9, Louise, 7, Victoria, 6, Maud, 4), They arrived in Rothbury on 19 August 1884 and left on 22 August in order to visit Cragside and Lord Armstrong. Firework displays were held by Pain's of London.[8]

David Dipper Dixon[]

David Dippie Dixon was a historian from Rothbury. He previously worked in his father's draper's shop, William Dixon and Sons, set up in Coquetdale House (now the Co-op). After William Dixon died, David Dippie Dixion and his brother John Turnbull Dixon renamed the shop Dixon Bros.[8]

21st century[]

2006 royal visit[]

On 9 November 2006, Rothbury was visited by another Prince of Wales, Edward VIII's 2nd Great Grandson, Prince Charles, visited with his wife Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall. Prince Charles visited to reopen the refurbished Rothbury village hall, Jubilee Hall, originally built in 1897 and named after the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, his 3rd Great Grandmother.[11][12][13] The royal couple also visited Rothbury Family Butchers, whose owner, Morris Adamson, said:

“I talked to them for about 20 minutes about the business. It was almost surreal, staggering. They were both very well informed about the trade, and the Duchess really impressed me with her knowledge and enthusiasm. I put together for them a gift of Northumbrian lamb and specialist sausages and two days later they sent me a thank you letter from Clarence House saying how much they had enjoyed the visit and the meat. The Duchess told me in the shop that her son (Tom) was a food critic and she said she would recommend he should come up to see us in Rothbury to sample our speciality sausages. And Prince Charles congratulated us on keeping alive the traditions of the trade and providing meat that was sourced locally. He urged us to keep up the good work. It was amazing, really.”

Governance[]

Politics[]

County Council[]

Rothbury is served by the Northumberland County Council and represented by Councillor Steven Bridgett, first elected in 2008 as a Liberal Democrat and re-elected in 2013 and 2017 as an Independent.[14]

Parliament[]

Rothbury is in the parliamentary constituency of Berwick-upon-Tweed. The current representative is Anne-Marie Trevelyan of the Conservatives, who has been the local MP since 2015.

From 1973 until 2015, Rothbury's MP was Alan Beith, a member of the Liberal Democrats since 1988 and the Liberal Party prior to its merger with the Social Democratic Party, he is currently a member of the House of Lords.

European Union[]

Prior to Britain's withdrawal from the European Union, Rothbury was in the European Parliament constituency of North East England, represented predominantly by the Labour party.

Public services[]

Police[]

Rothbury is served by Northumbria Police and has a single police station, housed, since May 2019, in a building owned by the Northumberland National Park.[15]

Fire[]

Rothbury has a fire station. The fire station is staffed by on-call firefighters; They do not work at the fire station full-time but are paid to spend time on call to respond to emergencies. The station has a four by four fire engine. The building and its facilities are shared with Sure Start.[16]

Healthcare[]

The village is served by a doctor's surgery[17] and a hospital, Rothbury Community Hospital. The original facility was built as a private home known as Coquet House in 1872.[18] It was converted into the Coquetdale Cottage Hospital in 1905.[18] A maternity ward was added, as a lasting memorial to soldiers who died in the Second World War, in 1946.[18] It joined the National Health Service in 1948[19] and the adjoining Hawthorn Cottage was acquired in 1956.[18] After Hawthorn Cottage had been converted into a physiotherapy department, it was officially re-opened by Jimmy Savile in 1990.[18] After the old hospital became dilapidated, modern facilities were built in Whitton Bank Road and opened in 2007.[18] The new hospital closed to inpatients in September 2016[20] and in June 2019 the trust advised that a group was working on proposals for the future of remaining services at the hospital.[21] The closure caused controversy [22] and a local protest was established called Save Rothbury Cottage Hospital.[23][24] Rothbury's (Conservative) MP, Anne-Marie Trevelyan discussed the closure in Parliament on 9 March 2017.[25][26]

Geography[]

Rothbury is located in Northumberland, England, on the River Coquet, it is 13.5 miles (21.7 km) northwest of Morpeth and 26 miles (42 km) of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is located on the edge of the Northumberland National Park.[27] Rothbury has two Zone 6 B roads going though it: West to East is the B6341, Rothbury's main street, Front Street, is part of this B road;[28] The second B road is the B6342, its starting point is in Rothbury, and is connected to the B6341, it is part of Rothbury's Bridge Street before going over the River Coquet on the Rothbury Bridge and going South for 23.4 miles (37.7 km) connecting to the A68 (Dere Street) at the hamlet of Colwell[29] Rothbury also has the B6344 on the eastern edge, it is connected to the B6341 and goes southeast for 5.6 miles (9.0 km) passing though the hamlet of Pauperhaugh and connecting to the A697 at the hamlet of Weldon Bridge.[30]

Demography[]

Ethnicity[]

| Ethnic Group | 2011 [31] | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | % | |

| White: Total | 2086 | 99.0 |

| White: English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 2068 | 98.1 |

| White: Irish | 4 | 0.2 |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | 1 | 0.0 |

| White: Other white | 13 | 0.6 |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 9 | 0.4 |

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 7 | 0.3 |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 1 | 0.0 |

| Asian or Asian British: Asian Other | 1 | 0.0 |

| Black or Black British | 3 | 0.1 |

| Other | 1 | 0.0 |

| Total | 2107 | 100.0 |

Note: An ethnic group that is not on the table means that no one from

that ethnic group was recored being present in Rothbury at the

time of the census.

Religion[]

| Religion | 2011 [31] | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | % | |

| All usual residents | 2,107 | 100.0 |

| Has religion | 1,480 | 70.2 |

| Christian | 1,466 | 69.6 |

| Buddhist | 2 | 0.1 |

| Muslim | 2 | 0.1 |

| Other religion | 10 | 0.5 |

| No religion | 477 | 22.6 |

| Religion not stated | 150 | 7.1 |

Note: A religion that is not on the table means

that no practitioner of that religion was recored

was present in Rothbury at the time of the census.

Landmarks[]

Rothbury's Anglican parish church building – All Saints' Church – dates from circa 1850, largely replacing but in parts incorporating the fabric of a former Saxon edifice, including the chancel, the east wall of the south transept and the chancel arch. The church has a font with a stem or pedestal using a section of the Anglo-Saxon cross shaft, showing what is reputed to be the earliest carved representation in Great Britain of the Ascension of Christ.[32]

The Anglo-Saxon cross is not to be confused with the market cross near the church, the current version of which was erected in 1902 and is known as "St Armstrong's Cross" as it was paid for by Lady Armstrong, widow of Lord Armstrong of Cragside.[33] Until 1965, Rothbury was the location of a racecourse, which had operated intermittently since April 1759, but seldom staged more than one meeting per year. The course was affected by flooding in the 1960s, and the last meeting was on 10 April 1965. The site is now used by Rothbury Golf Club.[34]

Half a mile to the south, Whitton Tower is an exceptionally well-preserved 14th-century pele tower.[35]

Lordenshaw Hill has the largest concentration of rock carvings in Northumberland. Over 100 panels have been recorded on the hill, the adjacent Whitton Burn and Garleigh Moor, in an area which covers less than 620 acres. The carved panels range from single cup-marked boulders to complex panels. There are many other interesting archaeological sites in this area, including a ditched Iron Age enclosure and an Early Bronze Age cairn.[36]

Transport[]

The town was the terminus of a branch line from Scotsgap railway station on the North British Railway line from Morpeth to Reedsmouth. The line opened on 1 November 1870, the last passenger trains ran on 15 September 1952 and the line closed completely on 9 November 1963.

The railway station was located to the south of the River Coquet, and the site has been reused as an industrial estate, where the only obvious remains are one wall of the engine shed, which has become part of an engineering workshop.[37] The old Station Hotel still stands near the site, but is now known as The Coquetvale Hotel. It was built in the 1870s by William Armstrong, as a suitable place for visitors to his house at Cragside to be accommodated.[38]

The town is now served by an Arriva North East bus service which runs via Longframlington, Longhorsley, Morpeth and continues to Newcastle upon Tyne, the nearest city. PCL Travel, a local bus company, operates infrequent services to Alnwick. It also runs services roughly three times a day to Morpeth via Longframlington and Longhorsley.

Education[]

Rothbury has two schools:

- Rothbury First School - a community school for 3 to 9-year-olds of both genders (this type of school is state-funded, with the local education authority employing the staff, being responsible for the school's admissions and owning the school's estate). The school can accommodate 126 pupils and currently has 94.[39][40]

- Dr Thomlinson Church of England Middle School - founded in 1720, and for 9 to 13-year-olds of both genders, the school is run by the academy trust The Three Rivers Learning Trust.[41] The school can accommodate 258 pupils and currently has 232.[42][43]

Rothbury is in the catchment area for The King Edward VI School, Morpeth, also run by The Three Rivers Learning Trust.

Culture and community[]

Music[]

Rothbury Traditional Music Festival[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Rothbury holds the annual Rothbury Traditional Music Festival. It consists music concerts as well as competitions within the genre of folk music, mainly being that of traditional Northumberland folk music, .[44] In 2013, the festival was featured on Northumberland born TV Presenter and actor Robson Green's documentary series Tales from Northumberland with Robson Green (Season one, Episode five).[45] In 2019, TV presenter and singerAlexander Armstrong, who was born in Rothbury, was made patron of the festival,[46] in 2021 Armstrong announced the return of the Music Festival from an erupting Icelandic volcano in a video posted on on the Facebook page of the Festival after it was cancelled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[47] Notable music acts that have performed at the festival include:

2015:[48]

- Dan Walsh, banjoist

- Chris Parkinson, co-founder of the British folk band The House Band

- Jez Lowe, County Durham folk singer-songwriter

- Folkestra, The Sage Gateshead’s youth folk ensemble

2021:[51]

- Martin Carthy, influential folk singer and guitarist.

Rothbury Hills[]

Rothbury has a song about it called "Rothbury Hills," written by Jack Armstrong in 1944.[52] It has been sung by Kathryn Tickell on her 2009 album "Northumberland Collection",[53] and by Alexander Armstrong on his 2015 album "A Year of Songs".[54]

Rothbury Highland Pipe Band[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Rothbury has its own pipe band, called the Rothbury Highland Pipe Band. The band was established on the 1st June 1920 then being named the Rothbury Kilted Pipe Band. The tartan chosen for their kilts was taken from the army regiment the Seaforth Highlanders, as during World War One some of their soldiers were stationed in Coquetdale and developed friendships with the local people. They reformed in the 1950s, being renamed the Rothbury Highland Pipe Band. The band has appeared on the TV show The White Heather Club. [55][56][57]

Football[]

Rothbury has its own football club: Rothbury FC, the club is in Division One of the Northern Football Alliance, which is on level 11 of the National League System.[58][59]

| 29 August 2018 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Rothbury FC | 3–0 | Burradon FC | showRothbury |

| 25 August 2018 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Wideopen And District | 2–7 | Rothbury FC | showNewcastle upon Tyne |

| 22 August 2018 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Ellington FC | 0–2 | Rothbury FC | showAshington |

| 18 August 2018 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Rothbury FC | 4–1 | Coundon & Leeholme FC | showRothbury |

| 15 August 2018 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Rothbury FC | 2–1 | Spittal Rovers | showRothbury |

| 11 August 2018 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Blyth FC | 4–2 | Rothbury FC | showBlyth |

| 1 May 2019 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Rothbury FC | 2–2 | Coundon & Leeholme FC | showRothbury |

| 4 May 2019 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Rothbury FC | 1–2 | Whitburn & Cleadon FC | showRothbury |

| 8 May 2019 Team Valley Carpets 2nd Division | Rothbury FC | 3–0 | Stobswood Welfare | showRothbury |

| 19 December 2020 Northern Football Alliance | Rothbury FC | 1–0 | Wallsend Boys Club | showRothbury |

| TBD Northern Football Alliance | Rothbury FC | v | Red Row Welfare F.C. | showTBD |

| TBD Northern Football Alliance | Rothbury FC | v | Whitley Bay Sporting Club | showTBD |

| TBD Northern Football Alliance | Rothbury FC | v | Bedlington FC | showTBD |

| TBD Northern Football Alliance | Rothbury FC | v | Prudhoe Youth Club FC | showTBD |

| TBD Northern Football Alliance | Rothbury FC | v | Felling Magpies | showTBD |

| TBD Northern Football Alliance | Rothbury FC | v | Cramlington United F.C. | showTBD |

Folklore[]

In Rothbury folklore Simonside Hills overlooking Rothbury has a mythical creature called a deaugar or duergar (Norse for 'dwarf'). It is said that the creature lures people at night by its lantern light towards bogs or cliffs in order to kill them.[60] The deaugar has entered into Rothbury's popular culture: in 2021 local musician and poet James Tait wrote a debut children's book called The World of Lightness: A Story of the Duergar of Simonside;[61][62] an annual 10-mile winter nighttime trail run in the Simonside Hills is called the Duergar Nightcrawler;[63] and a Rothbury art gallery is named Red Deaugar Art Gallery, run by local artist Margaret Bodley Edwards, a descendant of Gothic Revival architect George Frederick Bodley (1827–1907), and of diplomat and founder of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, Sir Thomas Bodley (1545–1613).[64]

Bedlington Terrier[]

The Bedlington Terrier was originally named after Rothbury and known as the Rothbury or Rodbury Terrier however the name changed due to popularity of the breed by miners in the Northumberland pit village of Bedlington[65]

Crime[]

1919 armed robbery of Rothbury Brewery[]

On the night of the 28 February 1919 two Russian sailors, Peter Klighe and Karl Strautin, broke into the Rothbury Brewery. At around 9:00 pm, patrol officer PC Francis Sinton was walked past the Brewery, he approached it after hearing noises of the men inside. As he did so he told a passer-by named James Curry to fetch the manager, Mr Farndale. As PC Sinton approached the brewery one of the two men appeared from it and shot at Sinton, missing him only slightly, and the two began to tussle as the second man appeared from the brewery and smashed Sinton's head with an iron bar, allowing the two robbers to escape. Curry and Farndale arrived finding PC Sinton laying on the ground and the assailants missing. After an extensive police search around Northumberland, the two perpetrators Klighe and Strautin were found in Walbottle Dene. Despite being armed with a pistol they gave themselves up. Klighe and Strautin were found wearing clothes stolen from the Ashington Co-Op, where they also broke into the safe. They were suspected of breaking into a number of safes across the region. They were charged with attempted murder and sentenced to penal servitude for 13 years. PC Sinton was awarded the King's Police Medal. A newspaper dubbed the crime a "Wild West Drama".[66]

1993 armed robbery of post office[]

Overnight on 23 and 24 August 1993, an organised crime gang robbed the Rothbury post office of £15,000 (≈ £30,000 in 2020)[67] in cash, stamps and pension books. Armed with iron crowbars and dressed in camouflage and ski masks they cut the telephone wires, blocked the main road with a stolen council van, and threatened local residents.

The then MP for Rothbury, Liberal Democrat Alan Beith said the event showed rural villages like Rothbury needed extra police cover to fight organised crime. Detective Inspector John Hope, who lead the investigation, stated that too much of focus on cities lead to organized crime moving to rural villages. He also said that improving roads to give better police access to rural villages would help decrease crime, and that the criminal justice system was failing to convict people, with criminals knowing they could escape punishment.[8][68]

2010 Northumbria Police manhunt[]

In July 2010, Rothbury was the site of a major police manhunt. Raoul Moat was released from HM Prison Durham on 1 July, after an 18-week sentence for assaulting a nine-year old relative. During his prison sentence, his girlfriend had a relationship with a police officer that she kept secret from Moat; his business also collapsed while he was in prison, which he blamed the police for. After his release, he discovered his girlfriend's relationship; he shot and killed her new boyfriend, 29-year-old karate instructor Chris Brown, and attempted to kill her. Then, while driving on the A1, he attacked police officer David Rathband, stationed in a patrol car on the roundabout of the A1 and A69 roads near East Denton, permanently blinding him (Rathband would hang himself at home in Blyth 18 months later). Moat then went on the run for five days (3-8 July), hiding in and around Rothbury. Police then cornered him by the river on the night of 8 July. After a six-hour stand-off, with Moat holding a gun to his head the entire time, Moat committed suicide by shooting himself early on the morning of 9 July.

2021 Pub Robberies and Cannabis Farm Discovery[]

In May 2021 burglars broke into two pubs, the Newcastle House in Rothbury, stealing £4,000 and The Three Wheats in Thropton stealing £150. The landlord of The Three Wheats, Gail Hooper, called the burglars "scumbags".[69]

In June 2021 police discovered a cannabis farm at the closed-down pub The Railway Hotel in Rothbury, the police said that "At about 2.20pm on Monday we received a report from an electric company that a cannabis farm had been found inside the Railway Hotel pub in Rothbury. Officers attended the scene and about 100 plants were removed and destroyed. A 25-year-old man was arrested and has since been charged with producing a Class B drug".[70]

Notable people[]

- Alexander Armstrong (born 1970), actor, comedian, and co-presenter of Pointless, was born in Rothbury

- Imogen Stubbs (born 1961), actress, was born in Rothbury

Places named after Rothbury[]

Rothbury, New South Wales

Rothbury, New South Wales North Rothbury, New South Wales (named after the larger town of Rothbury to the south that ultimately is named after Rothbury, Northumberland)

North Rothbury, New South Wales (named after the larger town of Rothbury to the south that ultimately is named after Rothbury, Northumberland) Rothbury, Michigan

Rothbury, Michigan

In popular culture[]

Film[]

- Moonlight Sonata (1937) is a film shot at Cragside. It was directed by Lothar Mendes, written by Edward Knoblock and E. M. Delafield, and starred the former Prime Minister of Poland, Ignacy Jan Paderewski.[8][71]

- The Boy and the Bus (2014), a short film (23 minutes long) directed by Simon Pitts, written by Rod Arthur, and featuring actors Ali Cook and Tracey Wilkinson, was filmed in Rothbury.[72]

TV[]

Documentary[]

- The Restoration Man (2010–present), is a home improvement show presented by architect George Clarke, the renovation of Thrum Mill by locals Dave and Margaret Heldey into a home was featured on the show in Series 3: Episode 4 (2014) and Clarke's revisiting of the mill a year later in Series 4: Episode Eight (2015).

External video  The Restoration Man: Renovation of Thrum Mill (46:58). DIY Daily - Home & Garden. (YouTube)

The Restoration Man: Renovation of Thrum Mill (46:58). DIY Daily - Home & Garden. (YouTube) - Car SOS (2013–present), is show which restores classic cars in disrepair without the owner knowing, the owner being nominated for the show by a relative or friend, the owner is then surprised with their finished car in a staged event. The renovation of localman Tom Mason's 1934 Morgan F4 three-wheeler was featured in Series 3: Episode 4 (2015).

Drama[]

Vera (2011–present, a ITV crime drama had scenes from two episodes filmed in Rothbury:[73][74]

- Silent Voices (Season 2 Episode 2) at Thrum Mill,[75] and

- Darkwater (Season 8 Episode 4) at Simonside Hills[76]

Line producer Margaret Mitchell commented on filming at Rothbury for Darkwater:[77]

“We arrived very early in the morning, on an October day when it was very misty. The sun was rising and shone through the water – that was particularly beautiful. It's a great place for walking. When you're here, you're completely struck by the expansive land, the light and the skies. You can see the vast panorama of countryside, the light just fills your eyes. It's incredible.”

Rothbury was also mentioned by DS Joe Ashworth (David Leon) in the episode 'Poster Girl', Series 3: Episode 2.

Gallery[]

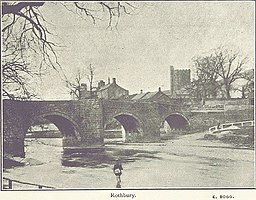

Rothbury looking over the River Coquet on the north bank to the Bridge and All Saint's Church (1898)

View of the village from Whitton Bank, on the northside of the River Coquet, to the southside, where the majoirty of the village stands.

Bridge over the Coquet at Rothbury. This pedestrian bridge links the car park (right) with the town (left).

Looking west along Front Street (B6341), in the foreground, and High Street, in the background, running parallel to Front Street.

Looking to the junction of Front Street (B6341), in the foreground running left ro right, and Church Street, this street leads from Town Foot to All Saints church.

Newcastle Hotel, on the junction of Front Street (B6341), foreground, and Church Street, right.

Church Street with the Newcastle Hotel to its left, connecting to Front Street (B6341), in the foreground running left to right.

Barclays Bank, the building stands at the junction of Bridge Street and Town Foot (B6341).

Looking northeast along Bridge Street, in the background Town Foot (B6341) can be seen connecting to it.

Bibliography[]

- Beckensall, Stan (2001). Northumberland The Power of Place. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-1907-7.

- Finlayson, Rhona; Hardie, Caroline; et al. (2009). "Rothbury Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey" (PDF). Northumberland County Council.

- Graham, Frank (1975). Rothbury and Coquetdale. Northern History Booklet No. 65. ISBN 978-0-85983-092-8.

References[]

- ^ "Parish population 2011". Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Finlayson., Rhona; Hardie, Caroline (2009). "Rothbury Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey" (PDF). Northumberland County Council: 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scott, Andrew (2012). "The early railways of North East England and their heritage today". The International Conference on Business & Technology Transfer. 2012 (6): 141. doi:10.1299/jsmeicbtt.2012.6.0_141. ISSN 2433-295X.

- ^ Hazell, Zoë; Crosby, Vicky; Oakey, Matthew; Marshall, Peter (November 2017). "Archaeological investigation and charcoal analysis of charcoal burning platforms, Barbon, Cumbria, UK". Quaternary International. 458: 178–199. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2017.05.025. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ "Newcastle, Northumberland County, New Brunswick". 1959: 8. doi:10.4095/110227. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c Graham, Frank (1975). Rothbury and Coquetdale (Northern History Booklet No. 65). ISBN 978-0-85983-092-8.

- ^ Beckensall, (2001), Stan (2001). Northumberland The Power of Place. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-1907-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Chronology | Rothbury". rothbury.co.uk. 1993. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ [1].

- ^ Girouard 1979, p. 307.

- ^ "Rothbury Jubilee Institute Hall: About the hall". www.rothburyjubileehall.org.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Rothbury Jubilee Institute Hall: History". www.rothburyjubileehall.org.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Past Engagements | Prince of Wales". www.princeofwales.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Councillor details - Councillor Steven Christopher Bridgett". northumberland.moderngov.co.uk. 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Northumbria Police set to move to new base secured for officers in Rothbury". beta.northumbria.police.uk. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Local fire stations - Our fire stations - Rothbury". Northumberland County Council.

- ^ "The Rothbury Practice". Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Cottage Hospital". Rothbury.co.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Coquetdale Cottage Hospital". National Archives. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Ray of light for Rothbury community over closed inpatient beds". Northumberland Gazette. 14 November 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Future of Rothbury hospital to be decided in the autumn following closure of beds two years ago". The Chronicle. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Ray of light for Rothbury community over closed inpatient beds". www.northumberlandgazette.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Save Rothbury Cottage Hospital". Facebook. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Graham, Hannah (28 August 2019). "Victory in sight in three-year battle to save rural hospital beds". ChronicleLive. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Rothbury Community Hospital - Thursday 9 March 2017 - Hansard - UK Parliament". hansard.parliament.uk. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Parliamentlive.tv". parliamentlive.tv. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Rothbury • Northumberland National Park". Northumberland National Park. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "B6341 - Roader's Digest: The SABRE Wiki". www.sabre-roads.org.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "B6342 - Roader's Digest: The SABRE Wiki". www.sabre-roads.org.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "B6344 - Roader's Digest: The SABRE Wiki". www.sabre-roads.org.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Custom report - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics". www.nomisweb.co.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "All Saints Rothbury". Parish of Upper Coquetdale. Retrieved 29 October 2018.; see also Hawkes, Jane (1996). "The Rothbury Cross: An Iconographic Bricolage". Gesta. 35 (1): 77–94. doi:10.2307/767228. JSTOR 767228. S2CID 193289467.

- ^ Watson, June. "Rothbury, Northumberland". Durham & Northumberland Ancestry Research. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010.

- ^ "Rothbury Racecourse". Greyhound Derby. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ "Whitton Tower". Pastscape. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "Walking With Rock Art – 7. Lordenshaw". rockart.ncl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012.

- ^ "Rothbury site record". Disused Stations. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ "Coquetvale Hotel". coquetvale.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to Rothbury First School". www.rothburyfirst.northumberland.sch.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Rothbury First School - GOV.UK". www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "THE THREE RIVERS LEARNING TRUST - GOV.UK". www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Dr Thomlinson C of E Middle School | Where every child matters, Every child succeeds". drthomlinson.the3rivers.net. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Dr Thomlinson Church of England Middle School - GOV.UK". www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Rothbury Traditional Music Festival – a weekend of traditional music, dance and events". Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ "RECAP: Further Tales from Northumberland '" Episode Five". www.northumberlandgazette.co.uk. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Alexander Armstrong announced as patron of Rothbury traditional music festival". North East Times. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Our ace Patron, TV's Alexander Armstong announces the festival from an Erupting /Icelandic Volcano! Festival is ON! Saturday 10th July with outdoor stage from 12.30pm-5pm". Facebook. 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Programme 2015". Rothbury Traditional Music Festival. 2015.

- ^ "2019 FESTIVAL DATES ARE 19TH – 21ST JULY: 2019 ARTISTS ANNOUNCED!". Rothbury Traditional Music Festival. 2019.

- ^ Rothbury Traditional Music Festival 2019 Programme. https://www.dropbox.com/s/m03jz0dcqdffihp/Programme%20v9%20no%20bleed.pdf?dl=0. 2019. pp. 3–4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ "Performers 2021". Rothbury Traditional Music Festival.

- ^ "Rothbury Hills". Traditional Tune Archive. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Northumberland Collection, retrieved 23 March 2021

- ^ A Year of Songs, retrieved 23 March 2021

- ^ Dawson, Peter; Murray, Billy. "Rothbury Highland Pipe Band". www.rothburypipeband.co.uk.

- ^ Scott, Katie (16 July 2020). "History of the Rothbury Highland Pipe Band as it celebrates its centenary". Northumberland Gazette.

- ^ Scott, Katie (30 July 2020). "Rothbury Highland Pipe Band's 'World Tours' inspired by comedian Billy Connolly". Northumberland Gazette.

- ^ "Rothbury Football Club". www.rothburyfc.com.

- ^ "Viewing Club: Rothbury FC". Northern Football Alliance.

- ^ [Green, Malcolm (2014). Northumberland Folk Tales. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-0-7524-8998-8.]

- ^ "The World of Lightness". www.jamestait.co.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Tait, James (2021). The World of Lightness: A Story of the Duergar of Simonside. Wanney Books. ISBN 9781999790585.

- ^ Duergar Run website. Accessed: 23 March 2021

- ^ "Margaret Bodley Edwards – a talented and remarkable woman who cares about giving artistic opportunities to all". www.northumberlandgazette.co.uk. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Folklore has it that the Bedlington Terriers were used by Romani people of the Rothbury Forest to hunt silently for small game and the livestock of the landowners: Kerry V. Kern, "The Terrier Handbook"; Barron's Edu. Ser., 2005 New York.

- ^ Green, Nigel. Tough Times and Gristly Crimes: A History of Crime in Northumberland. Wallsend, Tyne and Wear: Stonebrook Print and Designs. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-9551635-0-0.

- ^ "Inflation calculator". www.bankofengland.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Crime gangs 'targeting rural areas': Audacious raid on village and". The Independent. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Larkin, Paul (8 May 2021). "Burglars target two Northumberland pubs in one night". Northumberland Gazette.

- ^ Smith, Ian (9 June 2021). "Man charged after cannabis farm discovered at Northumberland pub". Northumberland Gazette.

- ^ Fendley, Alan (2014). The Jubilee Hall (PDF). D.W.Elson. p. 10.

- ^ Pitts, Simon (4 April 2014), The Boy and the Bus (Short, Drama, Family), Ali Cook, Gregory Floy, Angela Gillbanks, Philip Harrison, retrieved 12 January 2021

- ^ Hodgson, Barbara (16 January 2020). "Where is Vera's filmed? Check out locations used in the ITV drama". ChronicleLive. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ "Where is 'Vera' filmed? Here are major shooting locations of the British show". Republic World. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ "Vera" Silent Voices (TV Episode 2012) – IMDb, retrieved 12 January 2021

- ^ Jones, Lee Haven (28 January 2018), Darkwater (Crime, Drama, Mystery), Brenda Blethyn, Kenny Doughty, Jon Morrison, Kingsley Ben-Adir, ITV Studios, retrieved 13 January 2021

- ^ "Discover the setting of ITV's detective drama Vera". Radio Times. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rothbury. |

- Rothbury: The Village

- Rothbury Photos

- GENUKI (Accessed: 7 November 2008)

- Northumberland Communities (Accessed: 7 November 2008)

- Rothbury

- Towns in Northumberland

- Civil parishes in Northumberland

- History of Northumberland