SMS Frauenlob

Frauenlob passing under the Levensau High Bridge in the Kiel Canal

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Frauenlob |

| Laid down | 1901 |

| Launched | 22 March 1902 |

| Commissioned | 17 February 1903 |

| Fate | Sunk during the Battle of Jutland, 31 May 1916 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Gazelle-class light cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 105 m (344.5 ft) loa |

| Beam | 12.4 m (40.7 ft) |

| Draft | 4.99 m (16.4 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph) |

| Range | 4,400 nmi (8,100 km; 5,100 mi) at 12 kn (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Frauenlob ("His Majesty's Ship Frauenlob")[a] was the eighth member of the ten-ship Gazelle class of light cruisers that were built for the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) in the late 1890s and early 1900s. The Gazelle class was the culmination of earlier unprotected cruiser and aviso designs, combining the best aspects of both types in what became the progenitor of all future light cruisers of the Imperial fleet. Built to be able to serve with the main German fleet and as a colonial cruiser, she was armed with a battery of ten 10.5 cm (4.1 in) guns and a top speed of 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph). Frauenlob was a modified version of the basic Gazelle design, with improved armor and additional coal storage for a longer cruising range.

Following her commissioning in early 1903, Frauenlob served in the reconnaissance force for the main German fleet. During this period, she took part in routine training exercises, visits to foreign ports, and training cruises, including a trip to Spain in 1903. Her crew won prizes for excellent shooting among the fleet's cruisers in 1906 and 1907, the former being the first year the prize was awarded to cruisers. In January 1908, the ship was decommissioned and placed in reserve for the next six years.

The ship was reactivated in August 1914 after the start of World War I, and she saw action at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August, where she and the cruiser Stettin badly damaged the British cruiser HMS Arethusa. She took part in fleet operations for the next two years, culminating in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916. There, she saw little action in the early stages of the battle, but in one of the chaotic night engagements as the Germans tried to disengage and return home, Frauenlob was hit by a torpedo launched by the cruiser HMS Southampton, which caused the ship to capsize and sink with the vast majority of her crew. The wreck was discovered in 2000, and is in remarkably good condition, sitting upright on the ocean floor.

Design[]

Following the construction of the unprotected cruisers of the Bussard class and the aviso Hela for the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy), the Construction Department of the Reichsmarineamt (Imperial Navy Office) prepared a design for a new small cruiser that combined the best attributes of both types of vessels. The designers had to design a small cruiser with armor protection that had an optimal combination of speed, armament, and stability necessary for fleet operations, along with the endurance to operate on foreign stations in the German colonial empire. The resulting Gazelle design provided the basis for all of the light cruisers built by the German fleet to the last official designs prepared in 1914.[1][2] After the first seven ships had been built or were under construction, the Construction Department improved the design slightly, strengthening the armor on the conning tower and increasing the beam, which allowed more space for coal storage, and thus a longer cruising radius. These changes were applied to the last three members of the class: Frauenlob, Arcona, and Undine.[3]

Frauenlob was 105 meters (344 ft 6 in) long overall and had a beam of 12.4 m (40 ft 8 in) and a draft of 4.99 m (16 ft 4 in) forward. She displaced 2,706 t (2,663 long tons) normally and up to 3,158 t (3,108 long tons) at full combat load. Her propulsion system consisted of two triple-expansion steam engines manufactured by AG Weser. They were designed to give 8,000 metric horsepower (7,900 ihp), for a top speed of 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph). The engines were powered by eight coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers. Frauenlob carried 700 t (690 long tons) of coal, which gave her a range of 4,400 nautical miles (8,100 km; 5,100 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). She had a crew of 14 officers and 256 enlisted men.[4]

The ship was armed with ten 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/40 guns in single mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, six were located amidships, three on either side, and two were placed side by side aft. The guns could engage targets out to 12,200 m (13,300 yd). They were supplied with 1,500 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun. She was also equipped with two 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes with five torpedoes. They were submerged in the hull on the broadside. The ship was protected by an armored deck that was 20 to 25 mm (0.79 to 0.98 in) thick. The conning tower had 80 mm (3.1 in) thick sides, and the guns were protected by 50 mm (2 in) thick gun shields.[4]

History[]

Early career[]

Frauenlob was ordered under the contract name "G" and was laid down at the AG Weser shipyard in Bremen in mid-1901. She was launched of 22 March 1902; owing to space limitations, she was launched sideways, rather than stern-first. Vizeadmiral (Vice Admiral) gave a speech at the launching ceremony, and the new ship was christened by Anna Reuss, Princess of Stolberg-Wernigerode. She was named for the schooner Frauenlob, launched in 1853, that had been paid for in part by the donations of women from the German lands; the name means "praise women." The cruiser was commissioned for sea trials on 17 February 1903 under the command of Korvettenkapitän (KK—Corvette Captain) . After a three-day endurance test passing through the Skagerrak, Kattegat, and the Danish straits, Frauenlob arrived in Kiel, where she was assigned to the reconnaissance force for I Squadron. She continued initial testing through 23 April, and on 7 May joined the fleet for a cruise to Spain that lasted until 10 June. A training cruise to Norwegian waters followed in July, and in September, the ship was drydocked in Wilhelmshaven for repairs and maintenance. She joined the fleet's battleships for their winter training cruise in November and December in the North and Baltic Seas.[5][6]

In January 1904, Frauenlob took part in another winter training cruise in the Skagerrak, and in March, the fleet's reconnaissance cruisers conducted a training cruise in the North Sea. The fleet held training exercises in May and June in the North and Baltic Seas, which concluded with a naval review held in honor of the visit of King Edward VII of Great Britain. The German fleet made a visit to Britain, the Netherlands, and Norway in July and August. After their return to Germany in August, the ships conducted fleet maneuvers. Another winter cruise followed in November and December, this time in the Baltic. The year 1905 followed a similar pattern to the previous year with regard to training exercises and cruises abroad. On 2 May, she ran aground while departing Bremerhaven, damaging her rudder. From 26 to 28 August, she took part in a cruise in the Baltic with the British Channel Fleet on its way to visit Swinemünde. After the annual fleet maneuvers, she was drydocked in Wilhelmshaven for an overhaul, and in October, KK took command of the ship. She was docked again in December to have her hull thoroughly inspected for damage that might have been incurred during the grounding.[7]

The year 1906 passed largely uneventfully for Frauenlob. She took part in a large naval review held in September after the end of the autumn fleet maneuvers; the review was held for Grossadmiral (Grand Admiral) Hans von Koester, who was retiring at the end of the year. Frauenlob won Kaiser Wilhelm II's Schiesspreis (Shooting Prize) for excellent gunnery during that year's maneuvers; up to this time, he had previously only awarded one to each of the fleet's battleship squadrons. During torpedo practice, she accidentally torpedoed and sank her own steam pinnace. In addition to the year's training activities, Frauenlob conducted a training cruise to familiarize navigation officers with the narrow waterways of the Danish straits in 1907. She also won the Schiesspreis for cruisers again that year. In October, KK Friedrich Boedicker replaced Mischke as the ship's captain. By 1908, she was the only member of her class still in active service, and on 19 January she, too, was decommissioned in Wilhelsmhaven. She spent the next six years in reserve, though beginning in mid-1912, she was thoroughly overhauled and four of her 10.4 cm guns were removed to install ten 3.7 cm (1.5 in) guns for training purposes, though she was not activated for this role.[7]

World War I[]

Battle of Heligoland Bight[]

Frauenlob was recommissioned into the fleet on 2 August 1914 as a result of the outbreak of World War I. She was initially assigned to before being transferred to the newly-created on 25 August. When the British raided the German defensive patrols in the Helgoland Bight on 28 August, resulting in the Battle of Heligoland Bight, Frauenlob was anchored off Helgoland as distant support of the patrol line. The British raiders—the Harwich Force—consisted of two light cruisers and thirty-three destroyers under Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt. Frauenlob received reports of the attack at 08:00 from returning picket boats.[8][9][10] At about 09:00, Frauenlob and the light cruiser Stettin were sent out to reinforce the beleaguered German patrols.[11]

Frauenlob and Stettin shortly thereafter encountered the British cruiser HMS Arethusa and about six destroyers and they opened fire at 09:09. The ships quickly found the range and hit the British ship an estimated 25–35 times, disabling all but one of her guns and inflicting serious damage. One shell detonated a cordite charge and set Arethusa on fire. The ship's engine room flooded and her speed fell to 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph). She turned away to starboard in order to escape from the punishing fire, but Frauenlob kept up with the badly damaged British cruiser until she disappeared in the fog. In return, Frauenlob was hit ten times, but was not seriously damaged; in all, five men were killed and another thirty-two were wounded. After the engagement ended, Frauenlob and the torpedo boat V3 took the badly damaged minesweeper under tow and returned her to Heligoland, before proceeding to Wilhelmshaven.[9][12]

After completing repairs, Frauenlob joined the High Seas Fleet when it sailed in support of the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group during the raid on Yarmouth on 3–4 November. A similar operation followed on 15–16 December, resulting in the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby. She also took part in fleet sorties in March, April, May, September, and October 1915; none of these resulted in contact with British warships. During the operation on 17–18 May, she steamed in front of the fleet to detonate any naval mines that might have been laid by British minelayers. In late October, she was drydocked for an overhaul, during which time her crew was sent to operate the cruiser Danzig. Frauenlob returned to service in time for another fleet operation on 23 March 1916 that resulted in no contact with enemy forces.[9]

- Frauenlob at the Battle of Heligoland Bight

Light cruiser Arethusa, the main opponent of Frauenlob at Helgoland

Actions of Mineseeker-Division III with aiding maneuvers of Frauenlob

Actions of Frauenlob in the Battle of Heligoland Bight

Frauenlob steaming at speed

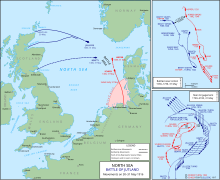

Battle of Jutland[]

In late May, the German fleet commander, VAdm Reinhard Scheer, planned to conducted another fleet operation. The plan called for the battlecruiser squadron to steam north to the Skagerrak, with the intention of luring out a portion of the British fleet so it could be destroyed by Scheer's waiting battleships. The Germans had at their disposal sixteen dreadnought battleships, six pre-dreadnoughts, and five battlecruisers, along with numerous cruisers and torpedo boats. In the early hours of 30 May, the German fleet got underway Frauenlob remained with IV Scouting Group for the operation, which was at that time under the command of Kommodore (Commodore) Ludwig von Reuter and was tasked with screening the High Seas Fleet. Unknown to the Germans, the Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. The Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[13]

The initial action was fought primarily by the British and German battlecruiser formations in the afternoon, but by 18:00, the Grand Fleet approached the scene and the two main battle fleets engaged.[14] Frauenlob was not actively engaged in the battle until later on the evening of 31 May; at around 21:15, IV Scouting Group encountered the British 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron and briefly engaged them, but due to the poor visibility, only Stettin and München fired for long, and to no effect.[15]

Later, during the chaotic night fighting, the battlecruisers Seydlitz and Moltke passed too closely in front of Stettin, which forced all of the ships of IV Scouting Group to fall out of line, inadvertently bringing them into contact with the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron. A ferocious firefight ensued, at a range of only 730 meters (2,400 ft). Frauenlob opened fire on HMS Southampton and HMS Dublin, as did the rest of IV Scouting Group. In return, Southampton launched a torpedo that struck Frauenlob at around 22:35, which cut her power and caused serious flooding. British 6-inch (152 mm) shellfire set the deck alight, and the stricken cruiser quickly capsized and sank with heavy loss of life. John Campbell reports that twelve officers and 308 men were killed in the sinking,[16][17] while Hans Hildebrand, Albert Röhr, and Hans-Otto Steinmetz state that 324 died when Frauenlob sank. Both agree that only 9 men from her crew survived, having been picked up after the battle by a Dutch steamer and interned in the Netherlands for the rest of the war.[9][18]

Wreck[]

In 2000, the wreck was located by Danish divers. The British marine archaeologist Innes McCartney led a subsequent dive and confirmed that the wreck sits upright on the sea floor and is largely intact. Skeletal remains from the ship's crew are scattered around the sunken cruiser. The wreck was positively identified when McCartney's team recovered the ship's bell in 2001, which they donated to the Laboe Naval Memorial near Kiel, where the bell is currently on display.[19]

Notes[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

Citations[]

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Nottelmann, pp. 103–110.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 94.

- ^ a b Gröner, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 99–102.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 90, 93–94.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Staff, pp. 4, 8.

- ^ a b c d Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 95.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Scheer, p. 43.

- ^ Staff, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 61–64.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 37, 121.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 191–193.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 213–214.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Campbell, p. 281.

- ^ McCartney, Innes (1 March 2002). "In search of Jutland's wrecks". . Retrieved 27 October 2012.

References[]

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1991). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1557503527.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien: ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart (Band 3) [The German Warships: Biographies: A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present (Vol. 3)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0211-4.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). "The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 2765294.

- Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84884-182-6.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

- Gazelle-class cruisers

- Ships built in Bremen (state)

- 1902 ships

- World War I cruisers of Germany

- Maritime incidents in 1916

- Ships sunk at the Battle of Jutland