STS-29

TDRS-D being deployed on Flight Day 1 of the mission. | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1989-021A |

| SATCAT no. | 19882 |

| Mission duration | 4 days, 23 hours, 38 minutes, 52 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 3,200,000 kilometers (2,000,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 80 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch mass | 116,281 kilograms (256,356 lb) |

| Landing mass | 88,353 kilograms (194,785 lb) |

| Payload mass | 17,280 kilograms (38,100 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 13 March 1989, 14:57:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 18 March 1989, 14:35:51 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 22 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 297 kilometres (185 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 308 kilometres (191 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.5 degrees |

| Period | 90.6 min |

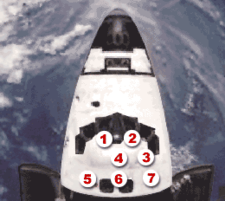

Back row, L-R: Bagian, Springer, Buchli. Front row, L-R: Blaha and Coats. | |

STS-29R was a NASA Space Shuttle mission, during which Space Shuttle Discovery inserted a Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) into Earth orbit.[1] It was the third shuttle mission following the Challenger disaster of 1986, and launched from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on 13 March 1989.[2] STS-29R was the eighth flight of Discovery and the 28th Space Shuttle mission overall; its planned predecessor, STS-28, was delayed until August 1989.

The mission was technically designated STS-29R as the original STS-29 designator belonged to STS-61A, the 22nd Space Shuttle mission. Official documentation and paperwork for that mission contained the designator STS-29 when it was allocated to Space Shuttle Columbia & later as STS-30 when allocated to Challenger. The 'R' stood for 'Recycled' or 'Re-manifested'. As STS-51L was designated STS-33, future flights with the STS-26 through STS-33 designators would require the 'R' in their documentation to avoid conflicts in tracking data from one mission to another.

Crew[]

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Michael L. Coats Second spaceflight | |

| Pilot | John E. Blaha First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Robert C. Springer First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | James F. Buchli Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | James P. Bagian First spaceflight | |

Crew seating arrangements[]

| Seat[3] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Coats | Coats | |

| S2 | Blaha | Blaha | |

| S3 | Springer | Bagian | |

| S4 | Buchli | Buchli | |

| S5 | Bagian | Springer |

Mission summary[]

Discovery lifted off from Pad B, Launch Complex 39, Kennedy Space Center, at 9:57 am EST on 13 March 1989.[4] The launch was originally scheduled for 18 February, but was postponed to allow for the replacement of faulty liquid oxygen turbopumps on the three main engines. The amended target date of 11 March was postponed by 1 day, because of the failure of a master event controller (MEC) #2 when it was powered up during prelaunch checkout,[5] as well as an additional day to replace a faulty fuel preburner oxidizer valve (FPOV).[5] On the rescheduled launch day of 13 March, the launch was delayed for nearly two hours because of ground fog and high upper winds.[5] A waiver was approved for the orbiter's wing loads.

The primary payload was the third and final component of the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS)[1] constellation in geosynchronous orbit. The three on-orbit satellites were stationed over the equator at about 22,300 miles above Earth; two of them were positioned 130 degrees apart, while the third was located between them as an on-orbit spare.

On Flight Day 1, one of three cryogenic hydrogen tanks which supplied shuttle's electricity-generating fuel cells exhibited erratic pressure fluctuations. It was deactivated while engineers studied the problem, and the crew was told to conserve electrical power. The tank was reactivated on Flight Day 3, 15 March, and operated successfully thereafter.[6]

Discovery landed on 18 March 1989, after orbit 80, one orbit earlier than planned, in order to avoid possible excessive wind buildup expected at the landing site. The shuttle touched down on Runway 22 at Edwards Air Force Base, California, at 9:35 am EST. The total mission duration was 4 days, 23 hours, and 39 minutes.[5]

Payload and experiments[]

The mission's primary payload was a Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-D),[5] which became TDRS-4 after deployment, and its attached Inertial Upper Stage (IUS). The satellite was deployed from the shuttle's payload bay less than six hours after launch, at 3:12 a.m. EST. The first-stage orbit burn of the IUS took place an hour later, and the second burn to circularize the orbit occurred 12 hours and 30 minutes into the mission. The satellite was stationed at 41.0° West longitude.

Discovery also carried eight secondary payloads, including two Shuttle Student Involvement Program experiments. One student experiment, using four live rats with tiny pieces of bone removed from their bodies, was to test whether the environmental effects of space flight inhibit bone healing. The other student experiment was to fly 32 chicken eggs to determine the effects of space flight on fertilized chicken embryos.[7]

One experiment, mounted in the payload bay, was only termed "partially successful". The Space Station Heat Pipe Advanced Radiator Element (SHARE), a potential cooling system for the planned Space Station Freedom, operated continuously for less than 30 minutes under powered electrical loads. The failure was blamed on the faulty design of the equipment, especially the manifold section.[8]

All other experiments operated successfully. Crystals were obtained from all the proteins in the Protein Crystal Growth experiment. The Chromosomes and Plant Cell Division in Space (CHROMEX), a life sciences experiment, was designed to show the effects of microgravity on root development. An IMAX (70 mm) camera was used to film a variety of scenes for the 1990 IMAX film Blue Planet,[9] including the effects of floods, hurricanes, wildfires and volcanic eruptions on Earth. A ground-based US Air Force experiment used the orbiter as a calibration target for the Air Force Maui Optical Site (AMOS) in Hawaii.[10]

Wake-up calls[]

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, and first used music to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[11]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer |

|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "I Got You (I Feel Good)" | James Brown |

| Day 3 | "Marine Corps Hymn" | |

| Day 4 | "Theme from Star Trek: TOS" | Alexander Courage |

| Day 5 | "Heigh-Ho" | Song from the Walt Disney animated film Snow White |

| Day 6 | "What a Wonderful World" | Louis Armstrong |

Gallery[]

Liftoff of STS-29.

The External Tank after separation.

Closeup shot of the deployment of TDRS-D.

Lake Natron, Tanzania, imaged from orbit.

See also[]

References[]

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "STS-29 Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. March 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021.

- ^ Dye, Lee (14 March 1989). "Space Shuttle Launched, Puts Satellite in Orbit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021.

- ^ Becker, Joachim. "Spaceflight mission report: STS-29". SPACEFACTS. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Chen, Adam (2012). Celebrating 30 Years of the Space Shuttle (PDF). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-16-090202-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Legler, Robert D.; Floyd V., Bennett (September 2011). "Space Shuttle Missions Summary" (PDF). Scientific and Technical Information (STI) Program Office. NASA. pp. 2-30–2-31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2020.

- ^ Office of Safety, Reliability, Maintainability and Quality Assurance (8 May 1989). "Misson Safety Evaluation Report for STS-29 - Postflight Edition" (PDF). Washington, DC: NASA. p. A-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Brown, Robert W. (1990). "NASA's Educational Programs" (PDF). Government Information Quarterly. 7 (2): 185–195. doi:10.1016/0740-624X(90)90054-R. hdl:2060/19900019131. ISSN 0740-624X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021.

- ^ Venant, Elizabeth (18 March 1989). "Astronauts Play Film Makers for IMAX 'Blue Planet'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021.

- ^ Viereck, R. A.; Murad, E.; Pike, C. P.; Kofsky, I. L.; Trowbridge, C. A.; Rall, D. L. A.; Satayesh, A.; Berk, A.; Elgin, J. B. (1990). Photometric analysis of a space shuttle water venting (PDF). Fourth Annual Workshop on Space Operations Applications and Research (SOAR 90). Houston, Texas: NASA. pp. 676–680.

- ^ Fries, Colin (13 March 2015). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). History Division. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

External links[]

- Space Shuttle missions

- Edwards Air Force Base

- Spacecraft which reentered in 1989

- Spacecraft launched in 1989

- March 1989 events