STS-51-L

Challenger launches at the start of STS-51L | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| Mission duration |

|

| Distance travelled | 29 km (18 miles) |

| Orbits completed | Failed to achieve orbit (96 planned) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Challenger |

| Launch mass | 1,217,990 kilograms (2,685,210 lb) |

| Landing mass | 90,584 kilograms (199,704 lb) (planned) |

| Payload mass | 21,937 kilograms (48,363 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 7 |

| Members |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | January 28, 1986, 16:38:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy Space Center, LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Destroyed | January 28, 1986, 16:39:13 UTC[a] |

| Landing site | KSC, SLF Runway 33 (planned)[1] |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 285.0 km |

| Apogee altitude | 295.0 km |

| Inclination | 28.45° |

| Period | 90.40 minutes |

| Epoch | Planned |

Back row (L–R): Ellison Onizuka, Christa McAuliffe, Gregory Jarvis, Judith Resnik. Front row (L–R): Michael J. Smith, Francis "Dick" Scobee, Ronald McNair. | |

STS-51-L (formerly STS-33) was the 25th mission of the United States Space Shuttle program, the program to carry out routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo; as well as the final flight of Space Shuttle Challenger.

Planned as the first Teacher in Space Project in addition to observing Halley's Comet for six days, the mission never achieved orbit; a structural failure during its ascent phase 73 seconds after launch from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39B on January 28, 1986, killed all seven crew members – Commander Dick Scobee, Pilot Michael J. Smith, Mission Specialists Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnik and Ronald E. McNair, and Payload Specialists Gregory Jarvis and Christa McAuliffe – and destroyed the orbiter.

Immediately after the disaster, President Ronald Reagan convened the Rogers Commission to determine the cause of the explosion. The failure of an O-ring seal on the starboard Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) was determined to have caused the shuttle to break-up in flight. Space Shuttle flights were suspended while the hazards with the vehicle were addressed. Shuttle missions resumed in September 1988 with STS-26, launched 32 months after the accident.

Planned mission[]

The tenth mission for Challenger, STS-51-L was scheduled to deploy the second in a series of Tracking and Data Relay Satellites, carry out the first flight of the "Shuttle Pointed Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy" (SPARTAN-203) / Halley's Comet Experiment Deployable in order to observe Halley's Comet, and carry out several lessons from space as part of the Teacher in Space Project and Shuttle Student Involvement Program (SSIP). The flight marked the first American orbital mission to involve in-flight fatalities. It was also the first American human spaceflight mission to launch and fail to reach space; the first such mission in the world had been the Soviet Soyuz 18a mission, in which the two crew members had survived. Gregory Jarvis was originally scheduled to fly on the previous shuttle flight (STS-61-C), but he was reassigned to this flight and replaced by Congressman Bill Nelson.[2]

Crew[]

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Francis R. Scobee Would have been second spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Michael J. Smith Would have been first spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Ellison S. Onizuka Would have been second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Judith A. Resnik Would have been second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Ronald E. McNair Would have been second spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 1 | Gregory B. Jarvis Would have been first spaceflight Hughes Space and Communications | |

| Payload Specialist 2 | S. Christa McAuliffe Would have been first spaceflight Teacher in Space | |

Backup crew[]

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Payload Specialist 1 | L. William Butterworth Would have been first spaceflight Hughes Space and Communications | |

| Payload Specialist 2[3] | Barbara R. Morgan Would have been first spaceflight Teacher in Space | |

| Morgan would be selected as a NASA astronaut in 1998 and flew on STS-118 in 2007 as a mission specialist. | ||

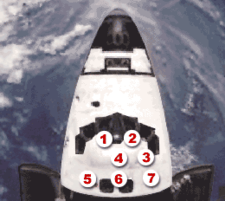

Crew seating arrangement[]

| Seat[4] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Scobee | Scobee | |

| S2 | Smith | Smith | |

| S3 | Onizuka | McNair | |

| S4 | Resnik | Resnik | |

| S5 | McNair | Onizuka | |

| S6 | Jarvis | Jarvis | |

| S7 | McAuliffe | McAuliffe |

Although the crew died in the Challenger disaster, their seating assignment chart depicts what would have happened if the mission had been performed as planned.

Ascent failure and disaster[]

During the ascent phase, 73 seconds after liftoff, the vehicle experienced a catastrophic structural failure resulting in the loss of crew and vehicle. The Rogers Commission later determined the cause of the accident to have been the failure of the primary and secondary (backup) O-ring seals on Challenger's right Solid Rocket Booster. The failure of these seals allowed a flamethrower-like flare to impinge upon one of two aft SRB attach struts, which eventually failed, freeing the booster to pivot about its remaining attachment points. The forward part of the booster cylinder struck the external tank inter-tank area, leading to a structural failure of the ET – the core structural component of the entire stack. A rapid burning of liberated propellants ensued. With the structural "backbone" of the stack compromised and breaking up, the SRBs flew off on their own, as did the orbiter, which rapidly disintegrated due to overwhelming aerodynamic forces. The launch had been approved despite a predicted ambient temperature of −3 °C (27 °F), well below the qualification limit of major components such as the SRBs, which had been certified for use only at temperatures above 4 °C (39 °F).[5] Evidence found in the remnants of the crew cabin showed that several of the emergency air supplies (PEAPs) carried by the astronauts had been manually activated, suggesting that forces experienced inside the cabin during breakup of the orbiter were not inherently fatal, and that at least three crew members were alive and capable of conscious action for a period following vehicle breakup.[6] "Tracking reported that the vehicle had exploded and impacted the water in an area approximately located at 28.64° north, 80.28° west".[7]

Crew fate[]

Divers from the USS Preserver located what they believed to be the crew cabin on the ocean floor on March 7. A dive the following day confirmed that it was the cabin and that the remains of the crew were inside.[8] No official investigation into the Challenger disaster has concluded for certain the cause of death of the astronauts; it is almost certain that the disintegration itself did not kill the entire crew as 3 of the 4 Personal Egress Air Packs (PEAPs) that were recovered had been manually activated. This would only be done during an emergency or loss of cabin pressure. PEAPs do not provide a pressurized air flow and would still have resulted in the astronauts losing consciousness within several seconds.[9] There were media reports alleging that NASA had a tape recording of the crew panicking and on-board conversation following the disintegration during the 2 minute 45 second free fall before hitting the sea east of Florida. This was likely fabricated and no recording exists, as the crew may have been unconscious from loss of cabin pressure and the astronauts did not wear individual voice recorders.[10] The impact of the shuttle with the sea would have killed any still surviving astronauts on board, though they may have died before the impact of other causes.

Mission objectives[]

- Deployment of Tracking Data Relay Satellite-B (TDRS-B) with an Inertial Upper Stage booster

- Flight of "Shuttle Pointed Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy" (SPARTAN-203)/Halley's Comet Experiment Deployable

- Fluid Dynamics Experiment (FDE)

- Comet Halley Active Monitoring Program (CHAMP)

- Phase Partitioning Experiment (PPE)

- Three Shuttle Student Involvement Program (SSIP) experiments

- Two lessons for the Teacher in Space Project (TISP)

- (unofficial) Ronald McNair was planning to play the saxophone in space for a track on Jean-Michel Jarre's album "Rendez-Vous".

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 Jan 1986, 3:43:00 pm | Rescheduled | — | Delays in STS-61-C[11] | |||

| 2 | 23 Jan 1986, 3:43:00 pm | Rescheduled | 1 day, 0 hours, 0 minutes | Delays in STS-61-C[11] | |||

| 3 | 24 Jan 1986, 3:43:00 pm | Scrubbed | 1 day, 0 hours, 0 minutes | Weather at transatlantic abort site[11] | |||

| 4 | 25 Jan 1986, 9:37:00 am | Scrubbed | 0 days, 17 hours, 54 minutes | Launch preparation delays[11] | |||

| 5 | 27 Jan 1986, 9:37:00 am | Scrubbed | 2 days, 0 hours, 0 minutes | Equipment failures in orbiter closeout, cross winds at shuttle landing site.[11] | |||

| 6 | 28 Jan 1986, 9:37:00 am | Delayed | 1 day, 0 hours, 0 minutes | Technical issues with fire detection system.[11] | |||

| 7 | 28 Jan 1986, 11:38:00 am | Loss of vehicle and crew | 0 days, 2 hours, 1 minute | [11] |

Mission insignia[]

Dick Scobee asked Kennedy Space Center engineer Ernie Reyes to design the mission patch seen above to represent the mission of 51-L. In it, Challenger is depicted launching from Florida and soaring into space to carry out a variety of goals. Among the prescribed duties of the five astronauts and two payload specialists (represented by the seven stars of the U.S. flag) was observation and photography of Halley's Comet, backdropped against the U.S. flag in the insignia. Surnames of the crew members encircle the scene, with the payload specialists being recognized below. The surname of the first teacher in space, Christa McAuliffe, is followed by a symbolic apple.[12]

See also[]

- Apollo 1

- STS-51-L Mission timeline

- Space Shuttle Columbia disaster

- Space Shuttle program

- Challenger Center

Notes[]

- ^ Planned landing was to be scheduled on February 3, 1986, 17:12:00 UTC

References[]

- ^ a b "Mission Archives – STS-51L". NASA. January 19, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Mullane, Mike (2006). Riding Rockets. Simon and Schuster. pp. 204–205. ISBN 9780743276825.

- ^ "S. Christa Corrigan McAuliffe". Biographical Data. NASA. April 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "STS-51L". . Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Rogers Commission, Vol4 Part7

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Joseph P. Kerwin's letter to Admiral Truly nasa.gov

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Shuttle explodes; crew lost". Daily Leader, Frederick, Oklahoma, January 28, 1986.

- ^ Isikoff, Michael (March 10, 1986). "Remains of Crew of Shuttle Found". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ Harwood, William. "The Fate of Challenger's Crew". Space-Shuttle.com. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (November 2, 2006). "Challenger Deaths". Snopes.com. Urban Legends Reference Pages. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g "STS-51L Mission Archives". NASA. January 19, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Thomas, James A. (Gene) (2006). Some Trust in Chariots: The Space Shuttle Challenger Experience. Xulon Press. p. 197. ISBN 1-60034-096-2.

External links[]

- 1986 in spaceflight

- Space accidents and incidents in the United States

- Space Shuttle missions

- Space program fatalities

- Space Shuttle Challenger disaster

- Spacecraft launched in 1986

- 1986 in Florida

- January 1986 events

- Rocket launches in 1986