Saddle-backed Rodrigues giant tortoise

| Saddle-backed Rodrigues giant tortoise | |

|---|---|

| |

| Engraving of the only taxidermy specimen | |

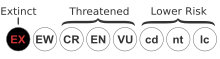

Conservation status

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | †Cylindraspis |

| Species: | †C. vosmaeri

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Cylindraspis vosmaeri Suckow, 1798

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The saddle-backed Rodrigues giant tortoise (Cylindraspis vosmaeri) is an extinct species of giant tortoise in the family Testudinidae. The species was endemic to Rodrigues. Human exploitation caused the extinction of this species around 1800.[3]

Etymology[]

The specific name, vosmaeri, is in honor of Dutch naturalist Arnout Vosmaer (1720–1799).[4]

Taxonomy[]

Both Cylindraspis vosmaeri and its smaller domed relative, Cylindraspis peltastes, were descended from an ancestral species on Mauritius (an ancestor of Cylindraspis inepta), which colonised Rodrigues by sea many millions of years ago, and then gradually differentiated into the two Rodrigues species.

Description[]

The saddle-backed Rodrigues giant tortoise was an exceptionally tall species of giant tortoise, with a long, raised neck and an upturned carapace, which gave it a giraffe-like body shape almost similar to that of a sauropod dinosaur.

It lived by browsing the taller vegetation, while its much smaller relative, the domed Rodrigues giant tortoise, grazed on low vegetation such as fallen leaves and grasses.

The saddle-backed Rodrigues giant tortoise was described by early colonists as a docile, gentle browser, with a tendency to gather in large herds, especially in the evening. An early Huguenot settler, in 1707, described the unusual group behaviour of these animals:

"There's one thing very odd among them; they always place sentinels, at some distance from the troop at the four corners of the camp, to which the sentinels turn their backs, and look with their eyes, as if they were on watch. This we have always observed of them; and this mystery seems the more difficult to be comprehended, for that these creatures are incapable to defend themselves..." (Leguat, 1707)[5]

Behaviour and ecology[]

It has subsequently been discovered that the browsing herds of giant tortoises filled an essential role in the ecosystem of Rodrigues and the regeneration of its forests. Among other roles, the giant tortoises ensured the dispersal and germination of tree seeds, as well as "terraforming" the island by maintaining forest clearings and pools.

In recognition of this fact, measures have been undertaken to introduce replacement species, in the form of similar giant tortoises from other parts of the world, to assist in the rebuilding of Rodrigues' devastated environment. The replacement species for the saddle-backed Rodrigues giant tortoise was chosen to be the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea) of the Seychelles, which is roughly similar in size, though very different in body form.[6]

Extinction[]

At the time of the arrival of human settlers, dense giant tortoise herds of many thousands were reported on Rodrigues. Typically for isolated island species, they were reported to have been friendly, curious, and unafraid of humans.

However, in the ensuing years, massive harvesting and exporting for food and the introduction of invasive species rapidly exterminated the giant tortoises. Tentative conservation efforts began in the 18th century, with the French Governor Mahé de Labourdonnais attempting to legislate against the "tortoise plundering" of Rodrigues. However, the wholesale slaughter continued. Hundreds of thousands were loaded into ships' holds for food, or to be transported to Mauritius where they were burnt for fat and oil. Due to their unusually thin shells, many died from crushing as they were densely stacked in the holds of ships.

In the final years, only smaller specimens were found, lingering in isolated mountainous refuges inland. A surviving giant tortoise was reported on the island in 1795, found at the bottom of a ravine. As late as 1802, there is a mention of survivors reportedly being killed in the large fires used to clear the island's vegetation for agriculture, but it is not clear which one of the two Rodrigues species these were, and which one survived the longest.[7]

References[]

- ^ World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Cylindraspis vosmaeri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T6065A12391587. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T6065A12391587.en. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 278–279. ISSN 1864-5755. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-17. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236899392_Using_a_surviving_lineage_of_Madagascar%27s_vanished_megafauna_for_ecological_restoration

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Cylindraspis vosmaeri, p. 276).

- ^ Leguat de la Fougère, François (1707-8). Voyage et avantures de François Leguat & de ses compagnons en deux îles déserte des Indes Orientales. Amsterdam: J.J. de Lorme. 2 vols. (in French).

- ^ Cheke A, Hume J (2008). Lost Land of the Dodo: An Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues. London: T & AD Poyser.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-12-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cylindraspis vosmaeri. |

Further reading[]

- Suckow, A. (1798). Anfangsgründe der theoretischen und angewandten Naturgeschichte der Thiere. Dritter Theil. Von den Amphibien. Leipzig: Weidmannischen Buchhandlung. 298 pp. (Testudo indica vosmaeri, new subspecies, p. 57). (in German).

- IUCN Red List extinct species

- Cylindraspis

- Reptile extinctions since 1500

- Extinct turtles

- Fauna of Rodrigues

- Reptiles described in 1798

- Species endangered by invasive species