Sahlen Field

"The House That Jimmy Built" | |

| |

A view of the field from lower-level seating, July 2021 | |

| |

| Former names | Pilot Field (1988–1995) Downtown Ballpark (1995) North AmeriCare Park (1995–1999) Dunn Tire Park (1999–2008) Coca-Cola Field (2009–2018) |

|---|---|

| Address | 1 James D. Griffin Plaza |

| Location | Buffalo, New York United States |

| Coordinates | 42°52′52.7″N 78°52′27.4″W / 42.881306°N 78.874278°WCoordinates: 42°52′52.7″N 78°52′27.4″W / 42.881306°N 78.874278°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | City of Buffalo[2] |

| Operator | Bison Baseball, Inc. |

| Executive suites | 26[5] |

| Capacity | 16,600 (2019–present)[6] 16,907 (2017–2018)[7] 17,600 (2015–2016)[8] 18,025 (2005–2014)[9] 21,050 (1990–2004)[9] 19,500 (1988–1989)[9] |

| Record attendance | Baseball: 21,050[10]

(June 3, 1990 / August 30, 2002) Concert: 27,000[11] (June 12, 2015) |

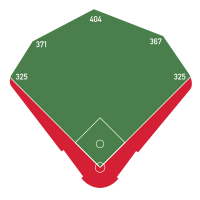

| Field size | Left field: 325 ft (99 m) Left-center field: 371 ft (113 m) Center field: 404 ft (123 m) Right-center field: 367 ft (112 m) Right field: 325 ft (99 m) Backstop: 55 ft (17 m)  |

| Surface | Kentucky Bluegrass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | July 10, 1986[1] |

| Opened | April 14, 1988 |

| Renovated | 2004, 2020, 2021 |

| Expanded | 1990 |

| Construction cost | US$42.4 million ($92.8 million in 2020 dollars[3]) |

| Architect | HOK Sport |

| Services engineer | Wendel Engineers PC[4] |

| General contractor | Cowper Construction Management |

| Tenants | |

| Buffalo Bisons (AA/IL/AAAE) 1988–present Buffalo Nighthawks (LPBL) 1998 Empire State Yankees (IL) 2012 Toronto Blue Jays (MLB) 2020, 2021 | |

Sahlen Field is a baseball park in Buffalo, New York. Originally known as Pilot Field, the venue has since been named Downtown Ballpark, North AmeriCare Park, Dunn Tire Park, and Coca-Cola Field. Home to the Buffalo Bisons of Triple-A East, it opened on April 14, 1988 and can seat up to 16,600 people, making it the highest-capacity Triple-A ballpark in the United States. It replaced the Bisons' former home, War Memorial Stadium, where the team played from 1979 to 1987.

The stadium was the first retro-classic ballpark built in the world, and was designed with plans for Major League Baseball (MLB) expansion. Buffalo had not had an MLB team since the Buffalo Blues played for the Federal League in 1915. However, Bisons owner Robert E. Rich Jr. was unsuccessful in his efforts to bring an MLB franchise to the stadium between 1988 and 1994. The stadium was a temporary home to the Toronto Blue Jays of MLB in 2020 and 2021 when they were displaced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sahlen Field was previously home to the Buffalo Nighthawks of the Ladies Professional Baseball League in 1998 and the Empire State Yankees of the International League in 2012. In addition to concerts and professional wrestling, the stadium has hosted major events including the National Old-Timers Baseball Classic (1988–1990), Triple-A All-Star Game (1988, 2012), StarGaze (1992–1993) and World University Games (1993).

History[]

Background[]

Buffalo began hosting professional baseball in 1877, when the Buffalo Bisons of the League Alliance began play at Riverside Park.[12] The Buffalo Bisons (IA) joined the International Association for Professional Base Ball Players in 1878, winning the league championship in their first season.

The Buffalo Bisons (NL) then defected to the National League of Major League Baseball in 1879. The Bisons moved to Olympic Park before the 1884 season, and left Major League Baseball following the 1885 season to join the Eastern League as the Buffalo Bisons.[12] The Eastern League was absorbed into the International League in 1887, but the league folded after a single season.

While the minor league Bisons continued play in the International Association for Professional Base Ball Players, an unaffiliated team also calling itself the Buffalo Bisons (PL) competed in the Players' League of Major League Baseball in 1890.[12] The minor league Bisons would rejoin the Eastern League in 1891, and later join the Western League in 1899. The Western League renamed itself the American League for the 1900 season, but the Bisons were replaced by the Boston Americans when the league joined Major League Baseball prior to the 1901 season.[13] The Bisons returned to the Eastern League, which was absorbed into the International League in 1912.

As the minor league Bisons continued play in the International League, an unaffiliated team called the Buffalo Blues competed in the Federal League of Major League Baseball in 1914 and 1915 at Federal League Park.[14] Bison Stadium was built for the Buffalo Bisons in 1924 at a cost of $265,000, and was later renamed Offermann Stadium following the death of team owner Frank J. Offermann in 1935.[15]

The Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League played at Offermann Stadium from 1951 to 1955. Hank Aaron was discovered while playing for the Clowns in 1952, and his contract was bought out by the Boston Braves for $10,000.[16] Toni Stone signed with the Clowns in 1953 for $12,000, becoming the first woman to sign a professional baseball contract.[17]

Buffalo was awarded an expansion franchise by the Continental League of Major League Baseball in January 1960, and made plans to play at War Memorial Stadium beginning with the 1961 season. However, the league folded before the season began.[18] The Bisons remained in the International League and began play at War Memorial Stadium in 1961, as Offermann Stadium had already been slated for demolition.

In April 1968, Robert O. Swados and his investment group, which included George Steinbrenner, presented their bid for a Buffalo expansion franchise to the National League Expansion Committee.[19][20] This bid included plans for a $50 million domed stadium that was designed by the architects of the Astrodome and had a capacity of 45,000.[21] Buffalo was one of five finalists for the 1969 Major League Baseball expansion, but franchises were awarded to the Montreal Expos and San Diego Padres in May 1968.[19]

Erie County went on to modify the planned domed stadium to accommodate the Buffalo Bills, approving its construction as a 60,000-seat football venue in Lancaster that could also host baseball.[22] However, bids for the stadium in 1970 came in over budget, and the project stalled. Bills owner Ralph Wilson threatened to move the Bills if action was not taken to replace the aging War Memorial Stadium, forcing Erie County to abandon the domed stadium in favor of building open-air Rich Stadium in Orchard Park.[23][24] The Buffalo Bisons moved mid-season in 1970 and became the Winnipeg Whips, leaving Buffalo without professional baseball.[25]

Planning and construction[]

Mayor James D. Griffin and an investment group purchased the Jersey City A's of the Double-A class Eastern League for $55,000 in 1978, and the team began play as the Buffalo Bisons at War Memorial Stadium in 1979.[26] This new franchise assumed the history of prior Buffalo Bisons teams that had played in the city from 1877 to 1970. Robert E. Rich Jr. purchased the Bisons for $100,000 in 1983, and upgraded the team to the Triple-A class American Association in 1985 after buying out the Wichita Aeros for $1 million.[27][28]

HOK Sport (now known as Populous) designed the downtown venue as the first retro-classic ballpark in the world.[29] The City of Buffalo originally hired HOK Sport to design a $90 million domed stadium with a capacity of 40,000 for the same parcel of land, but the project was scaled back after New York State only approved $22.5 million in funding instead of the $40 million requested.[30][31][32] The open-air venue was designed to fit within the neighborhood's existing architecture of the Ellicott Square Building, the Main-Seneca Building, Marine Midland Center and the Old Post Office. Located in close proximity to Buffalo Memorial Auditorium and along the newly built Buffalo Metro Rail, the venue would be an attractive and accessible destination for suburban residents.[33] The same design firm would later bring this concept to Major League Baseball with Oriole Park at Camden Yards.[34] The venue's exterior would be constructed from precast concrete, featuring arched window openings at the mezzanine level, rusticated joints, and inset marble panels. The baseball field itself would feature a Kentucky Bluegrass playing surface and have dimensions that were designed to mirror those of pitcher-friendly Royals Stadium.[35]

The $42.4 million venue was mainly paid for with public funding. $22.5 million came from New York State, $12.9 million came from the City of Buffalo, $4.2 million came from Erie County, and $2.8 million came from the Buffalo Bisons.[36] The New York State funding was contingent on the Bisons signing a 20-year lease with the City of Buffalo for use of the venue, which they did just prior to groundbreaking.[37] The City of Buffalo and Erie County paid an additional $14 million for the construction of parking garages to service the venue and other downtown businesses.[36]

St. John's Episcopal Church originally occupied what is now the venue's land at the corner of Swan Street and Washington Street, and Randall's Boarding House originally occupied the adjacent lot on Swan Street. Mark Twain famously was a resident of the boarding house while editor of the Buffalo Express.[38][39] Constructed between 1846 and 1848 on land donated by Joseph Ellicott,[40] the church remained in use until 1893 and was demolished in 1906.[41] The land then became the site of Ellsworth Statler's first hotel, Hotel Statler, in 1907.[41] It was later renamed Hotel Buffalo after Statler built a new hotel on Niagara Square in 1923 and sold his former location. Hotel Buffalo was demolished in 1968, and the land became a parking lot. The City of Buffalo would later acquire the land through eminent domain.[42]

The venue broke ground in July 1986 and was originally built with a seating capacity of 19,500,[9] which at the time made it the third-largest stadium in Minor League Baseball.[29] 38 luxury suites were constructed on the club level of the stadium.[43] The overall design allows for future expansion to accommodate a Major League Baseball team, as capacity could be increased to 41,530 by double-decking the existing mezzanine.[44][45]

Opening and reception[]

The venue opened in April 1988 and was lauded by mainstream media outlets, including feature stories by Newsday, New York Daily News, San Francisco Examiner, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times Magazine and Vancouver Sun.[46] Eric Brazil wrote that month in his San Francisco Examiner article that the venue, "just may be baseball's prototype for the 1990s and beyond".[47]

In their first year at the venue after moving from War Memorial Stadium, the Buffalo Bisons broke the all-time record for Minor League Baseball attendance by drawing 1,186,651 fans during the 1988 season.[48][49]

Pete McMartin wrote fondly of the venue in his June 1989 article for the Vancouver Sun, contrasting it with the recently opened SkyDome in Toronto:

I have seen the future of baseball and it looks a lot like the past. The best new ballpark in North America looks like the best old ballpark in North America. Forget SkyDome. Pilot Field, home to the Triple-A Buffalo Bisons baseball club, makes Toronto's newest toy look like a crass gimmick. It dares to offer the revolutionary concept of playing baseball on grass, open to the elements. And it does it in the prettiest playground in the game. Built last year for $42 million, (compared to SkyDome's half-billion), Pilot Field resembles a turn-of-the-century ballpark complete with soaring archways, exposed girders, palladian windows, and a copper-green metal roof above the stands topped with two cupolas. Its concrete facade has been "rusticated" to resemble the limestone walls of the heritage buildings in the downtown neighborhood that surround it. Pilot Field is so wildly popular with the citizens of Buffalo that it has helped rejuvenate Buffalo's once-decaying downtown. It was a matter of philosophy. Toronto built an edifice: Buffalo embraced an idea. Toronto elevated technology over the game: Buffalo honored the past. Buffalo ended up with the better ballpark. It may be the best ballpark built since the construction of the game's holy triumvirate - Wrigley, Fenway and Briggs.[50]

The inaugural Build New York Award was given to Cowper Construction Management in April 1990 by the General Building Contractors of New York State for their work on the venue.[51]

Alterations[]

Prior to the 1990 season, 1,400 bleacher seats and a standing-room only area within the third-base mezzanine were added at a cost of $1.34 million, increasing the stadium's capacity to 21,050.[52][53]

In September 1990, Robert E. Rich Jr. attempted to buy the Montreal Expos for $100 million and move the team to Buffalo, but owner Charles Bronfman declined his offer.[54] That same month, Rich Jr. and his investment group, which included Larry King, presented their bid for a Buffalo expansion franchise to the National League Expansion Committee.[55] However, by February 1991 the entry fee and startup capital needed for securing a Major League Baseball expansion franchise had skyrocketed to $140 million, and Rich Jr. declined the chance to secure additional investors.[56][57] Buffalo was one of six finalists for the 1993 Major League Baseball expansion, but franchises were awarded to the Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins in June 1991.[58]

In their fourth year at the stadium, the Bisons once again broke the all-time record for Minor League Baseball attendance by drawing 1,240,951 fans during the 1991 season.[59]

In June 1992, Rich Jr. attempted to buy the San Francisco Giants and move the team to Buffalo, but owner Bob Lurie declined his offer. The proposed name for the team would have been the New York Giants of Buffalo, as the franchise had previously played as the New York Giants from 1885 to 1957 in New York City.[54] That same month, the City of Buffalo chose to exercise an escape clause and buy back $24.2 million in federal bonds they had earmarked for expanding the venue to accommodate Major League Baseball.[60][61]

In July 1994, Rich Jr. notified the Major League Baseball Expansion Committee that he was interested in pursuing a Buffalo expansion franchise.[62] However, he would retract this notification the following month after the 1994–95 Major League Baseball strike commenced.[63] Buffalo was withdrawn as a candidate for the 1998 Major League Baseball expansion, and franchises were awarded to the Arizona Diamondbacks and Tampa Bay Devil Rays in March 1995.[64]

For the 1996 season, a new outfield fence was erected at the venue at a cost of $50,000 so the baseball field mirrored the dimensions of Jacobs Field. Left-center field was reduced from 384 feet to 371 feet, center field was reduced from 410 feet to 404 feet, right-center field was reduced from 384 feet to 367 feet, and the height of the center field fence was reduced from 15 feet to 8 feet. This change allowed the Cleveland Indians, Buffalo's major league affiliate, to better evaluate their prospects, while also making the park more hitter-friendly.[65]

In wake of the American Association disbanding following the 1997 season, the Bisons joined the International League in 1998. The addition of regional rivalries allowed for the creation of the Thruway Cup, an annual competition between the Buffalo Bisons, Rochester Red Wings and Syracuse SkyChiefs.[66]

The venue was home to the Buffalo Nighthawks of the Ladies Professional Baseball League before the league shut down mid-season in July 1998. The Nighthawks were in first place with an 11–5 record when the league folded, and were declared Eastern Division champions.[67]

The park's original four-color dot matrix scoreboard in center field was retrofitted with a 38-foot wide by 19-foot tall Daktronics LED video screen in 1999 at a cost of $1.2 million.[68][69]

The 20-year lease between the Bisons and City of Buffalo for use of the venue was renegotiated in January 2003, with the addition of funding from Erie County.[70]

Prior to the 2004 season, $5 million in renovations to the venue were completed, including removal of the stadium's right field bleachers and construction of a four-tier Party Deck in its place.[71] The removal of the bleachers decreased the stadium capacity to 18,025.[72]

The 20-year lease between the Bisons and City of Buffalo for use of the venue expired following the 2008 season, and the city began offering year-to-year leases to the team thereafter.[73]

A conference suite was constructed on the first-base side of the stadium in 2010 at a cost of $250,000. The year-round suite can accommodate business gatherings of up to 40 people.[74]

For the 2011 season, the park's original scoreboard in center field was removed and replaced by an 80-foot wide by 33-foot tall Daktronics high-definition LED video screen at a cost $2.5 million.[75] That same year, a new $970,000 field drainage system and a new $750,000 field lighting system were added to the venue.[76][77]

The venue was home to the Empire State Yankees of the International League in 2012. The team was forced to play at alternate sites that season as PNC Field was undergoing renovations.[78] The Yankees finished the season with a 84–60 record and advanced to the International League playoffs.

For the 2014 season, $500,000 was spent in improvements to the venue, including a new sound system and the installation of new LED message boards down both baselines.[79]

A campaign to replace the park's original red seating with wider green seating began in 2014. The stadium's capacity was reduced from 18,025 to 17,600 when 3,700 seats were replaced prior to the 2015 season at a cost of $758,000.[80][81] 2,900 seats were replaced prior to the 2017 season, reducing capacity of the stadium from 17,600 to 16,907.[7] 2,000 seats were replaced prior to the 2019 season, further reducing capacity to 16,600.[6][82]

Following the 2019 season, protective crowd netting was installed throughout the venue at a cost of $475,000 to meet Major League Baseball safety standards.[83]

In June 2020, the Bisons cancelled their season at the venue due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[84] The Toronto Blue Jays, the Bisons' major league affiliate, announced the following month that they would play their 2020 season at the venue after the government of Canada denied them permission to play at Rogers Centre.[85][86] The Blue Jays finished the season with a 32–28 record, and advanced to the American League Wild Card Series.[87] A Blue Jays locker from the stadium was preserved as an artifact in the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.[88]

Major League Baseball and the Blue Jays organization jointly funded renovations of the venue prior to the 2020 season at a cost of $5 million.[89] Permanent upgrades included installation of LED field lighting, installation of instant replay technology, installation of Hawk-Eye for Statcast tracking, a resurfaced infield, and relocation of the home dugout to the third-base side of the stadium. Temporary facilities designed for the postponed MLB at Field of Dreams game were also utilized.[90][91]

In the wake of the International League disbanding, the Bisons joined the newly formed Triple-A East in 2021.[92]

The Blue Jays once again utilized the venue for their 2021 season due to the ongoing pandemic, after having started the season at TD Ballpark. The Bisons accommodated this residency by relocating to Trenton Thunder Ballpark in Trenton, New Jersey.[93] The Bisons and Blue Jays jointly funded additional renovations of the venue prior to the 2021 season. These permanent upgrades included the installation of new light standards, new batting cages, new foul poles, a resurfaced outfield, and the relocation of both bullpens from foul territory to right-center field.[94]

Naming rights[]

Pilot Air Freight of Philadelphia purchased the 20-year naming rights to the venue in 1986.[95] The stadium would be named Pilot Field in exchange for the company paying the City of Buffalo $51,000 on an annual basis.[96] Their name was stripped from the venue by the City of Buffalo in March 1995 after defaulting on payments.

The stadium was then known as Downtown Ballpark until July 1995, when local HMO North AmeriCare purchased the naming rights and the stadium became North AmeriCare Park.[96] North AmeriCare agreed to pay the City of Buffalo $3.3 million over the course of 13 years.[97] The Dunn Tire chain of tire outlets assumed North AmeriCare's remaining contract with the City of Buffalo in May 1999, and the venue became Dunn Tire Park.[97]

Coca-Cola Bottling Company of Buffalo purchased the 10-year naming rights to the stadium in December 2008, and it was renamed Coca-Cola Field for the 2009 season.[98] Local meat packing company Sahlen's purchased the 10-year naming rights to the stadium in October 2018, and it was renamed Sahlen Field for the 2019 season.[99]

Notable events[]

Baseball[]

Opening Day of the venue's inaugural season took place on April 14, 1988, and saw the Buffalo Bisons defeat the Denver Zephyrs 1–0.[100] Pam Postema, the first female umpire in the history of professional baseball, officiated the game.[101] Prior to the event, The Oak Ridge Boys performed "The Star-Spangled Banner" and both Mayor James D. Griffin and Governor Mario Cuomo threw ceremonial first pitches.[101][102]

The formal dedication of the venue took place on May 21, 1988 prior to the Bisons defeating the Syracuse Chiefs in an interleague Triple-A Alliance game by a score of 6–5. Larry King threw the ceremonial first pitch and sat in on commentary with WBEN broadcasters Pete Weber and John Murphy.[103]

The seventh-annual National Old-Timers Baseball Classic was held at the venue in June 1988. The event aired on ESPN and saw the National League defeat the American League 8–2.[104]

The venue was host to the inaugural Triple-A All-Star Game in July 1988. The event aired live on ESPN and saw a team of American League-affiliated players defeat a team of National League-affiliated players 2–1.[105] Celebrity appearances were made by Morganna, the Kissing Bandit and Spuds MacKenzie.[106][107]

The eighth-annual National Old-Timers Baseball Classic was held at the venue in June 1989. The event aired on ESPN and saw the National League defeat the American League 8–7.[108]

The June 3, 1990, game between the Buffalo Bisons and Oklahoma City 89ers with a post-game concert by The Beach Boys set the all-time single-game attendance record for baseball at the venue with 21,050 fans. The Bisons lost the game 7–6.[109]

The ninth-annual National Old-Timers Baseball Classic was held at the venue in June 1990, which saw the National League defeat the American League 3–0.[110]

An exhibition between the Bisons and their Major League Baseball affiliate Pittsburgh Pirates took place at the venue in May 1991, with the Bisons winning the game 4–2.[111] Barry Bonds became the first player in the venue's history to hit a home run to center field during a pregame home run derby.[112] A second exhibition between the Bisons and Pirates took place in May 1993, with the Bisons winning the game 3–2.[113]

The venue hosted an exhibition between Team USA and Korea at the venue in July 1992, with Korea winning the game 4–2.[114] The exhibition was part of Team USA's 30-game tour of Cuba and the United States to promote their appearance in the 1992 Summer Olympics.[115]

The baseball events of the World University Games were held at the venue in July 1993.[116] Cuba defeated South Korea in the Gold Medal game 7–1.[117]

A viral video of Rich Aude pimping his walk-off home run to end a May 1994 game at the venue between the Bisons and Louisville Redbirds was covered by media outlets including Deadspin and MLB.com.[118][119][120]

An exhibition between the Bisons and their Major League Baseball affiliate Cleveland Indians took place at the venue in April 1995, with the Indians winning the game 2–1.[121]

A May 1995 game between the Buffalo Bisons and Iowa Cubs was the first-ever Triple-A game broadcast live by ESPN2. The Bisons lost this morning game, their annual School Day promotion, by a score of 5–1.[122]

Celebration of Baseball, an Old-Timers Game to benefit the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association was held at the venue in June 1995.[121][123]

The all-female Colorado Silver Bullets lost an exhibition to the all-male Queen City Rockers at the venue in July 1995 by a score of 2–1.[124][125]

An exhibition between the Bisons and their major league affiliate Cleveland Indians took place at the venue in June 1996, with the game ending in a 3–3 tie.[121]

Bartolo Colón of the Bisons threw a no-hitter at the venue in June 1997 against the New Orleans Zephyrs, sealing a 4–0 win.[121]

The venue was host to the Adam's Mark Celebrity Old-Timers Classic event in July 2000.[126]

An exhibition between the Bisons and Cleveland Indians took place in July 2002, with the Indians winning the game 4–3.[127][128]

An August 30, 2002, game between Buffalo and the Rochester Red Wings matched the all-time single-game attendance record for baseball at the venue with 21,050 fans. The Bisons won the game 5–0.[129]

In September 2004, the Bisons defeated the Richmond Braves at the venue in Game 4 of their championship series to win the Governors' Cup by a score of 6–1.[130]

A June 2010 game between the Bisons and Syracuse Chiefs was promoted as the final Triple-A appearance of Stephen Strasburg; he led the Chiefs to a 7–1 victory over the Bisons.[131][132]

The venue was host to the 25th-annual Triple-A All-Star Game in July 2012, which saw the Pacific Coast League defeat the International League 3–0.[133]

The venue's first Major League Baseball game took place on August 11, 2020, in which the Toronto Blue Jays defeated the Miami Marlins 5–4 in extra innings.[134]

Alek Manoah set a new Blue Jays franchise record for consecutive strikeouts with 7, sealing an 11–1 victory over the Tampa Bay Rays at the venue on July 2, 2021.[135]

Jonah Heim of the Texas Rangers became the first Buffalo native in 130 years to play a major league game in his hometown in their 10–2 loss to the Blue Jays at the venue on July 16, 2021. John Gillespie of the Buffalo Bisons was the last player from Buffalo to do so on October 1, 1890.[136]

Concerts[]

The Buffalo Bisons have presented a yearly post-game Summer Concert Series at the venue since 1988. The Summer Concert Series has included headlining performances by Aretha Franklin (1991),[137] Bill Cosby (1997),[138] Bo Diddley (1990),[139] Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra (1995–2019),[140] Chicago (1990, 1994),[139][141] Chubby Checker (1992),[142] Eddie Rabbitt (1988),[143] Foreigner (1994),[141] Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons (1990), Gloria Estefan (1988),[143] Huey Lewis and the News (1991),[137] Kansas (1996–1997),[144][145] KC and the Sunshine Band (1995),[146] Loverboy (1997),[145] Michael McDonald (1992),[142] Reba McEntire (1993),[147] Styx (1996),[144] The Beach Boys (1988–1995, 2000–2001),[148] The Doobie Brothers (1994),[141] The Monkees (2001),[149] The Temptations (1989),[150] The Turtles (1992),[142] Tommy James (1992),[142] Tony Bennett (1999),[151] Village People (1995)[146] and Willie Nelson (1989).[150]

The Budweiser Superfest music festival took place at the venue in July 1989 and included performances by Guy, Kool Moe Dee and New Edition.[152]

The Bluestime Jam music festival took place at the venue in August 1995 and included performances by B.B. King, Etta James and Jimmie Vaughan.[153]

The third-annual WEDG Edgefest music festival took place at the venue in June 1997 and included performances by Buck-O-Nine, David Usher, Goo Goo Dolls, Moist, Saturn Battery, Sloan, Tugboat Annie and Weezer.[154]

WKSE presented their annual Kiss the Summer Hello music festival at the venue from 2001 to 2002, and again from 2009 to 2013. Kiss the Summer Hello included headlining performances by 98 Degrees (2001),[155] Ashanti (2002),[156] Carly Rae Jepsen (2012),[157] Emblem3 (2013),[158] New Boyz (2010),[159] The Veronicas (2009)[160] and Travie McCoy (2011).[161]

WYRK has presented their annual Taste of Country music festival at the venue since 2001. The 2015 event headlined by Dierks Bentley set the all-time attendance record for concerts at the venue with 27,000 fans.[11]

WEDG staged their tenth-annual Edgefest music festival at the venue in May 2003, and it included performances by Cold, Finch, Hed PE, Klear, Powerman 5000, Seether, Smile Empty Soul, Staind, The Juliana Theory and Trapt.[162]

The second-annual Buffalo Niagara Guitar Festival took place at the venue in June 2003 and included performances by California Guitar Trio, Chris McHardy, Doug Yeaomans, Hubert Sumlin, Jim Weider, Johnny Hiland, Larry Coryell, Murali Coryell, Savoy Brown, Sid McGinnis and The Yardbirds.[162]

Counting Crows headlined a show at the venue in August 2007 as part of their Rock 'n' Roll Triple Play Ballpark Tour. They were supported by Collective Soul and Live.[163][164]

Professional wrestling[]

Ballpark Brawl was a series of post-game professional wrestling events produced by the Buffalo Bisons and promoted by Christopher Hill, their Director of Sales and Marketing between 2003 and 2007.[165] The promotion's Natural Heavyweight Championship paid homage to The Natural, which was filmed in Buffalo at War Memorial Stadium.

- Ballpark Brawl (August 2003) was headlined by Jeff Jarrett and Sabu defeating Disco Inferno and Raven.[166]

- Ballpark Brawl II: Field of Screams (July 2004) was headlined by Al Snow defeating Chris Candido.[167]

- Ballpark Brawl III: Canadian Carnage (August 2004) was headlined by AJ Styles defeating Sabu and Teddy Hart to become the inaugural Natural Heavyweight Champion.[168]

- Ballpark Brawl IV: fridaynightSMASH (July 2005) was headlined by Christopher Daniels defeating AJ Styles to become Natural Heavyweight Champion.[169]

- Ballpark Brawl V: Bang! Bang! Have a Nice Day! (August 2005) was headlined by The Sandman defeating Sabu, with Mick Foley as the guest referee.[170]

- Ballpark Brawl VI: Rochester Rumble (August 2005) took place at Frontier Field and was headlined by a 20-man battle royal.[171]

- Ballpark Brawl VII: Survival of the Fittest (August 2006) was headlined by Samoa Joe defeating Christopher Daniels, Homicide and Low Ki to become Natural Heavyweight Champion.[172]

- Ballpark Brawl VIII (August 2007) was headlined by Sterling James Keenan defeating Rikishi and Samoa Joe to become Natural Heavyweight Champion.[173]

TNA Wrestling held their unrelated BaseBrawl event at the venue in June 2011, headlined by Kurt Angle defeating Scott Steiner, and an appearance by Hulk Hogan.[174] TNA held another BaseBrawl event at the venue in June 2012, headlined by Bobby Roode defeating Jeff Hardy to retain the TNA World Heavyweight Championship.[175]

Other events[]

Reverend Billy Graham staged his Greater Buffalo-Niagara Crusade at the venue in August 1988.[176]

An ice skating rink was erected in the venue's outfield by the Greater Buffalo Chamber of Commerce for Winterfest III in January 1989.[177][178]

Goo Goo Dolls filmed the music video for their debut single "There You Are" at the venue in October 1990.[179]

Artist Jenny Holzer commandeered the venue's center field scoreboard in July 1991 to display her famed Truisms. She was in town to promote the opening of her Venice installation at the Albright–Knox Art Gallery.[180]

Jim Kelly held his inaugural StarGaze charity event at the venue in June 1992. The event drew a crowd of 14,500 and raised $150,000 for the Kelly for Kids Foundation.[181] The charity event returned in June 1993, drawing a crowd of 10,000 and raising $100,000 for the Kelly for Kids Foundation.[182]

A low-budget film called Angel Blues was shot at the venue in August 1993. It was directed by William Zabka and starred Michael Paloma, Loryn Locklin, Meredith Salenger, Richard Moll, David Johansen and Michael Horse.[183][184][185]

In July 1996, the Opening Ceremonies of the Empire State Games took place at the venue. Buffalo native Todd Marchant was the event's keynote speaker.[186]

The venue was home to the National Buffalo Wing Festival from 2002 to 2019.[187]

Reverend Franklin Graham staged his Evangelical outreach and music festival Rock the Lakes at the venue in September 2012.[188]

Nitro Circus brought their You Got This Tour, an extreme sports exhibition, to the venue in May 2019.[189]

Micah Hyde held his inaugural Charity Softball Game at the venue in June 2019. The event featured current and former members of the Buffalo Bills, and raised $40,000 for the Imagine for Youth Foundation.[190]

Special features[]

Dimensions[]

Crosby Spencer of RotoFanatic detailed the dimensions of Sahlen Field after the venue earned a hitter-friendly reputation during the 2020 Toronto Blue Jays season:

Sahlen Field’s center field sits facing South-Southeast with an 8 to 10 MPH breeze prevailing out from the right field foul pole to the left field foul pole all year long. Both the left field and right fields angle back from a 325 foot foul pole before squaring off at the power alleys (371 ft. LCF and 367 ft. RCF). The alleys then angle back inward forming a pointed A-Frame center field at 404 ft. Sahlen Field most resembles Nationals Park’s shape but it’s 12 feet shorter to left, 6 feet shorter to left-center, 2 feet deeper to center, 3 feet shorter to right-center and 10 feet shorter to right. Sahlen Field has definitely played as a very interesting park thus far. Despite the fact that left and left-center are the most offensively friendly fields it’s the left handed batters that have thrived the most. This does make some sense. The prevailing winds are out to left and opposite field balls are typically hit on a higher trajectory than pulled balls. This higher trajectory and steady winds gives the ball a chance to fly further than normal. Couple that with the friendly confines of 325 feet to left and 371 feet to the left-center alley and you have a recipe that serves up the number one ranked home run and RBIcon factors for left handed batters in all of baseball.[191]

Eateries[]

Consumer's Pub at the Park is a full service bar and restaurant located within the park's first-base mezzanine that features both indoor seating and outdoor patio seating with views of the field. It is open to the public year-round via an entrance on Washington Street, and exclusively to ticketholders on game days. The restaurant was formerly known as Pettibone's Grille from 1988 to 2016.[192]

Concessions around the venue's concourse feature selections from local eateries, including beef on weck from Charlie the Butcher, craft beer from Consumer's Beverage, hot dogs from Sahlen's, ice cream from Upstate Farms, pierogis from Ru's Pierogi, pizza from La Nova Pizzeria, and pizza logs from Original Pizza Logs.[193]

Union Pub is a full service bar and restaurant located directly across from the venue on Swan Street that has been in business since 1864.[194]

Tributes[]

The Buffalo Bisons have customarily marked the landing spot of every home run their players have hit into the right field parking lot since the venue's inaugural season in 1988.[195] This feat is rarely accomplished because the balls have had to clear either the right field bleachers or the Party Deck that replaced them in order to reach the parking lot. Russell Branyan holds the record for most parking lot home runs, with three.[196]

The original flag pole from center field at War Memorial Stadium was preserved and installed at the venue in July 1990. It can be found behind the Party Deck in right field, on land adjacent to the parking garage.[197]

Robert E. Rich Sr., the founder of Rich Products and father of Buffalo Bisons owner Robert E. Rich Jr., died in February 2006. His initials are inscribed on the press box, above the owner's suite, in tribute.[198]

Former Mayor of Buffalo James D. Griffin was posthumously honored by the Buffalo Common Council in July 2008 after they voted to change the venue's address to One James D. Griffin Plaza.[199] A bronze sculpture of Griffin titled The First Pitch, referencing his ceremonial first pitch at the venue's inaugural game, was unveiled outside the stadium in August 2012. The William Koch piece was commissioned by the Buffalo Bisons to honor Griffin's contributions in constructing the ballpark and bringing professional baseball back to Buffalo.[200]

Plaques honoring all members of the Buffalo Baseball Hall of Fame are on permanent display within the Hall of Fame and Heritage Room, which was built on the venue's third-base concourse in 2013.[201] The Heritage Room also contains rotating exhibits of memorabilia that honor Buffalo's baseball history.[202] It is open to ticketholders one hour prior to the first pitch on gamedays, and stays open through the third inning.[203]

The Bisons hang a Championship Corner banner in left field that commemorates the team's many league and division championships, along with the retired numbers of Ollie Carnegie (6), Luke Easter (25), Jeff Manto (30) and Jackie Robinson (42).[204]

Retired numbers of former Toronto Blue Jays players Roberto Alomar (12) and Roy Halladay (32), along with the retired number of Jackie Robinson (42), were inscribed above the venue's press box prior to the 2020 season. In addition, the number of former Toronto Blue Jays player Tony Fernández (1) was inscribed on the venue's outfield fence to honor his recent passing.[205]

Transportation access[]

Sahlen Field is located at the Elm Street exit (Exit 6) of Interstate 190, and within one mile of both the Oak Street exit of Route 33 and the Seneca Street exit of Route 5.[206]

An Allpro parking garage is located behind right field on Exchange Street, and a Buffalo Civic Auto Ramps parking garage is located within the Seneca One Tower complex. Both parking garages are connected by a pedestrian bridge over Washington Street. Multiple surface parking lots are also in the stadium's vicinity.

The venue is publicly served by Seneca Station of Buffalo Metro Rail. It is also served by Buffalo–Exchange Street station of Amtrak.

Vehicle for hire services including Uber and Lyft are available in the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Climate[]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[]

- Specific

- ^ "From the archives: Pilot Field". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "City of Buffalo and Bisons to Partner and Improve Experience at Coca-Cola Field". WGR. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ 1634 to 1699: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy ofthe United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700-1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How much is that in real money?: a historical price index for use as a deflator of money values in the economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ Maddore, James T. (April 19, 1991). "Wendel Engineers Plans New Building". The Buffalo News. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Renovation Project Yields Suite Results". MiLB.com. September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fink, James (March 23, 2019). "Buffalo Bisons freshen the ballpark lineup for 2019". Business First. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bisons unveil 2017 schedule & announce Phase 2 of ballpark seating project". Minor League Baseball. August 22, 2016. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Northrop, Milt (March 25, 2015). "Baseball Herd Changes Start with Seat Upgrade". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "2012 Buffalo Bisons Media Guide" (PDF). April 9, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 104.

- ^ Jump up to: a b O'Shei, Tim (June 13, 2015). "Taste of Country serves up a six-course delight". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "MLB returns to Buffalo for first time in 105 years: Exploring the city's rich baseball history". CBSSports.com.

- ^ "In Buffalo, the curse of Ban Johnson trumps even Cleveland's losing record".

- ^ Wawrow, John (July 25, 2020). "Buffalo to play home to Blue Jays considered a 'Natural'". The Washington Post. Associated Press.

- ^ "WATCH: Offermann Stadium Remembered | Buffalo Bisons News". Buffalo Bisons.

- ^ Graham, Tim (September 22, 2004). "Class Clowns The Indianapolis Clowns Have A Rich Place In Buffalo Baseball History; For Example, Hank Aaron Was "Discovered" At Offermann Stadium". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Richard, A.J. "Playing With The Boys: Gender, Race, and Baseball in Post-War America". SABR.org. Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ Bailey, Budd (January 29, 2011). "This Day in Buffalo Sports History: The majors in Buffalo?". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yates, Brock. "WARTS, LOVE AND DREAMS IN BUFFALO". Sports Illustrated Vault | SI.com.

- ^ https://buffalonews.com/news/local/history/buffalo-in-the-60s-george-steinbrenner--the-boss-loved-buffalo/article_8d6f712f-0901-52f4-bfd7-fc340416200d.html

- ^ "Buffalo New York Presentation to Major League Baseball".

- ^ "COUNTY PAYS $10 MILLION TO COTTRELL LONG FIGHT OVER DOME DRAWS TO A CONCLUSION".

- ^ "Herald-Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Erie County Loses Dome Suit". August 5, 1984 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "1970 Buffalo Bisons/Winnipeg Whips Roster". statscrew.com.

- ^ Moritz, Amy (July 14, 2017). "Buffalo's downtown ballpark: The house that Jimmy built". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "A Major League Effort for Buffalo". Los Angeles Times. September 6, 1988.

- ^ "The Daily Oklahoman from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma on September 8, 1984 · 72". Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kingston, Rachel (April 4, 2010). "Buffalo Among the "Top Ten Places for a Baseball Pilgrimage"". WBEN. Buffalo. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ "Buffalo is Building a Baseball Park". Los Angeles Times. May 31, 1987.

- ^ Roth, Stephen (April 12, 1999). "By design, they push limits of creativity". sportsbusinessdaily.com. Sports Business Journal.

- ^ "Buffalo's Efforts for Domed Stadium Are Dealt a New Blow". June 8, 1984 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Hamilton, Emily (July 29, 2020). "Want More Housing? Ending Single-Family Zoning Won't Do It". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

- ^ Kirst, Sean (April 12, 2018). "Sean Kirst: Buffalo's Pilot Field, an urban ballpark vision that swept nation". The Buffalo News.

- ^ https://buffalonews.com/news/buffalos-stadium-set-baseball-standard/article_839a90bb-cacf-5abb-aab0-0ed5aefc84a6.html

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rodgers, Kim (June 11, 1988). "Oh, how Buffalo loves its jewel". The Indianapolis News.

- ^ Fairbanks, Phil. "BISONS PLAYING HARDBALL BALLPARK LEASE COSTS TAXPAYERS AS TEAM PROSPERS". The Buffalo News.

- ^ https://buffalonews.com/news/new-study-indicates-twain-lived-on-the-line-in-pilot-field/article_a2c23518-2be0-5079-8cd9-a1d73dc1ab91.html

- ^ "THE CITY TWAIN KNEW FUND-RAISER CELEBRATES AUTHOR'S LIFE".

- ^ LaChiusa, Chuck (2002). "St. John's Grace Episcopal Church – History". Buffalo Architecture and History. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ellsworth Statler in Buffalo". Western New York Heritage Press, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ "Eminent domain played a roll in the development of two Buffalo sporting facilities - Buffalo Business First". webcache.googleusercontent.com.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (September 6, 1989). "AMERICAN JOURNAL". The Washington Post.

- ^ Collison, Kevin; Hammersley, Margaret (November 30, 1989). "Bisons Unveil Plans To Increase Pilot Field Capacity To 41,530 Upper Tier Would Be Added, Bleachers Converted". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Berkwitz, Steve (February 15, 1991). "Buffalo Reassesses Bid for Major League Team". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Warner, Gene (August 23, 1989). "National Media Anything But Cool To Buffalo Baseball's 'Hot' Status Swirl of Coverage Boosts Scouting Report, Big-League Hopes for City". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "And Here's The Pitch". The Buffalo News. August 11, 1989.

- ^ "Buffalo Bisons Set Minor League Attendance Mark". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. August 20, 1988. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Buffalo Bisons Franchise History (1878-2019)". statscrew.com.

- ^ McMartin, Pete (June 5, 1989). "Buffalo ball park shames Skydome". The Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "Ciminelli Cowper Co. Gets 'Build New York' Award". The Buffalo News. April 27, 1990.

- ^ Heaney, James; Turner, Douglas (January 17, 1990). "Pilot Field Expansion Clears Council Vote Also Backs Architectural Study of Facility Next To War Memorial Site". The Buffalo News.

- ^ https://milb.bamcontent.com/documents/1/4/2/308944142/2019_Buffalo_Bisons_Media_Guide.pdf

- ^ Jump up to: a b Felser, Larry (August 16, 1992). "Rich Says Battle to Obtain Big League Franchise Isn't Over". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Summer Ends at Pilot Field; Rich's Investor Group Buoys Big League Quest". The Buffalo News. September 6, 1990.

- ^ Zremski, Jerry (July 22, 1990). "Entry Fee May Be $168 Million For Big-League Team Cost of Expansion Franchise Could Shrink Contending Field". The Buffalo News.

- ^ O'Shei, Tim (May 26, 2017). "The Quiet Billionaire: Bob Rich is Still Buffalo's Ultimate Booster". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Chass, Murray (June 11, 1991). "Baseball Ready to Add Miami and Denver Teams". The New York Times.

- ^ Bailey, Budd (August 19, 2011). "This Day in Buffalo Sports History: Packing them in". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Pilot Field Funds Eyed for Arena Plan Would Finance Sabres' New Home with $24 Million Raised to Expand Stadium". The Buffalo News. February 22, 1992.

- ^ "Griffin Rejects Shift of Pilot Field Funds to New Sports Arena Decision Called 'Slight Setback'". The Buffalo News. May 2, 1992.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (July 16, 1994). "Despite Threat of Strike, Expansion Talk Surfacing". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Gaughan, Mark (August 12, 1994). "Rich Says No Thanks To Big Leagues Unrest, Economics Temper Present Interest of Herd Owner". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "MLB expands to Phoenix and Tampa". UPI.

- ^ "Fences Moving at North Americare Park This Summer". The Buffalo News. December 19, 1995.

- ^ "Triple-A still thriving after 1998 realignment". MiLB.com.

- ^ Starosielec, Mark (July 29, 1998). "Gates Close On Women's Baseball". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Buffalo Bisons to Install Largest LED Video Display in Minor League Baseball". daktronics.com. January 12, 2011.

- ^ https://buffalonews.com/news/herd-will-be-lighting-up-a-new-scoreboard-in-1999/article_2ebe3fce-e87f-572e-8e0e-12be47af379a.html

- ^ "Off-season Wrap-up". OurSports Central. February 20, 2003.

- ^ Pignataro, T.J. (April 17, 2004). "Party Deck Helps Revive Spirit at BallPark's Opener". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 137.

- ^ https://buffalonews.com/sports/baseball/professional/city-bisons-agree-to-3-year-lease-extension/article_a16dc2ba-3d31-553b-b154-9db7cfa2f46e.html

- ^ https://www.bizjournals.com/buffalo/stories/2010/05/31/story9.html

- ^ Arrington, Blake (March 30, 2011). "HD Scoreboard Highlights What's New". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Bisons to install new $2.5M videoboard - Buffalo Business First". webcache.googleusercontent.com.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (January 13, 2011). "Bisons getting HD scoreboard, new lights". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Empire State Yankees". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (February 24, 2014). "Bisons to Unveil New Message Boards, Sound System on Opening Day at Coca-Cola Field". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Bisons, City of Buffalo Announce Installation of New Seats in Special Reserved Sections". Minor League Baseball. August 22, 2014. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 22, 2014). "Updated: Bisons to Replace 3,700 Seats As Phase I to 'overhaul' of Coca-Cola Field". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ https://buffalonews.com/sports/baseball/professional/plenty-of-new-amenities-around-sahlen-field-international-league/article_7937eccb-f8e7-5bde-87ac-abf0055dd243.html

- ^ "Mayor Brown announces completion of nearly $759,000 in scheduled upgrades to Sahlen Field". The Buffalo Chronicle. August 13, 2020.

- ^ "Bisons will not play in 2020 as Minor League Baseball seasons are canceled". milb.com. June 30, 2020.

- ^ Vera, Amir; Ly, Laura; De La Fuente, Homero (July 18, 2020). "Canada denies Toronto Blue Jays' request to play home games due to pandemic". CNN.

- ^ Davidi, Shi (July 24, 2020). "Blue Jays to play majority of home games at Buffalo's Sahlen Field". Sportsnet.ca.

- ^ https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/TOR/index.shtml

- ^ @CDNBaseballHOF (December 10, 2020). "Newest artifact into our collection..." (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ https://www.bizjournals.com/buffalo/news/2020/09/22/sahlen-field-blue-jays.html

- ^ Harrington, Mike (July 24, 2020). "What has to be done to get Sahlen Field ready for MLB, Blue Jays". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "How Blue Jays transformed Sahlen Field into their temporary home - Sportsnet.ca". www.sportsnet.ca.

- ^ https://www.sportsnet.ca/mlb/article/buffalo-bisons-join-triple-east-remaining-top-toronto-blue-jays-affiliate/

- ^ https://www.milb.com/news/bisons-temporary-home-relocation-trenton

- ^ https://buffalonews.com/sports/baseball/whats-new-at-sahlen-field-for-the-blue-jays/article_692f998e-c302-11eb-a4f7-e795adc6b415.html

- ^ "Pilot Air's revenues are flying high". The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 29, 1987.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bailey, Budd (March 2, 2011). "This Day in Buffalo Sports History, March 2, 1995: Pilot Field's name changed". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fairbanks, Phil (May 4, 1999). "Dunn Tire is Looking to Pay Ballpark Figure of 2.5 Million". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (December 17, 2008). "Goodbye, Dunn Tire Park. Hello, Coca-Cola Field!". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ "Sahlen Field – the new home of the Herd". Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (March 31, 1997). "There's No Place Like Home, Baseball in Buffalo Celebrates 10 Years at its Downtown Location". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mario Cuomo – Society for American Baseball Research".

- ^ Campbell, Jon. "Gov. Andrew Cuomo, defying history, hasn't thrown a first pitch. Is this the year?". Democrat and Chronicle.

- ^ "Bisons mourn passing of Larry King, who was set to join their MLB ownership group". The Buffalo News. January 23, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "NL Old Timers Win". Hutchinson News. Associated Press. June 21, 1988.

- ^ "Triple-A All-Star Game Results (1988-1992)". tripleabaseball.com.

- ^ Harrington, Mike. "Buffalo born Triple-A game returns to city all grown up". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on April 13, 1988 · Page 44". Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harrington, Mike; Summers, Robert J. (June 18, 1989). "Old-Timers Game Represents Classic Case of Nostalgia". The Buffalo News.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (June 3, 1990). "Sloppiness Foils Herd in 7-6 Loss". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike; Summers, Robert J. (June 25, 1990). "Baseball's Greats Set For Third -- Perhaps Last -- Hurrah At Pilot". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 134.

- ^ Bailey, Budd. "This Day in Buffalo Sports History: Bonds, Barry Bonds". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Gaughan, Mark (May 7, 1993). "Pirates, Bisons Put Pitchers on Exhibit Struggling Hurlers Make Impressive Showings in 3-2 Win". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "USA Slump Continues Against Korea Americans Manage Just Five Hits in Loss at Pilot Field".

- ^ http://mlb.mlb.com/usa_baseball/downloads/y2007/1992_Media_Guide.pdf

- ^ "WORLD UNIVERSITY GAMES; Cuban Player Takes Intentional Walk". The New York Times. July 11, 1993.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (July 17, 1993). "Unmatched Cuba Runs, Hits, Fields Its Way To Gold Medal In Baseball". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Nobody Has Ever Pimped A Home Run As Hard As This Guy Did". Deadspin.

- ^ "Throwback Thursday: One of the Most Dramatic Bat Flips in History". MLB.com.

- ^ "AUDE LIFTS BISONS WITH HOMER, FROSTS REDBIRDS WITH TROT - Sports - The Buffalo News". October 19, 2015. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (May 4, 1995). "Cubs Complete Three-Game Sweep of Bisons". The Buffalo News.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (June 17, 1995). "Swoboda Returns with Other Stars for Celebration Former Mets Hero Joins 16 Other Baseball Greats Today". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Northrop, Milt (July 6, 1995). "Silver Bullets Firing First Shots Toward A Larger Goal". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Northrop, Milt (July 8, 1995). "Silver Bullets Impressive, But Women's Team Falls, 2-1 Outcome Disappoints Turnout of 2,500". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (July 16, 2000). "Fans Let Rose Know Where He Belongs". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 136.

- ^ "IL News & Notes". oursportscentral.com. International League. July 4, 2002.

- ^ Moritz, Amy (August 31, 2002). "Herd's Goelz Shines In Packed House". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Bisons Win 2004 Governors' Cup". oursportscentral.com. September 17, 2004.

- ^ "Bisons/Chiefs Game on Thursday to Air Nationally". oursportscentral.com. International League. June 2, 2010.

- ^ Kramer, Lindsay (June 3, 2010). "Strasburg goes out strong: five scoreless innings in Syracuse Chiefs' 7-1 win over Buffalo". Syracuse.com.

- ^ "Triple-A All-Star Game Results (2008-2012)". tripleabaseball.com.

- ^ Davidi, Shi (August 11, 2020). "Blue Jays christen Buffalo home with walk-off win over Marlins". Sportsnet.ca.

- ^ "Alek Manoah dominates Rays in return". MLB.com. July 3, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Bronstein, Jonah (July 17, 2021). "Rangers catcher Jonah Heim receives warm welcome from hometown crowd in Buffalo". Dallas News. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Beach Boys, Huey Lewis Top Bison Concert Series". The Buffalo News. April 29, 1991.

- ^ Violanti, Anthony (July 23, 1997). "In the Midst of a Rough Year, Bill Cosby Heads To Buffalo". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pop Music Notes". The Buffalo News. April 30, 1990.

- ^ "The great WNY summer tradition returns on a Friday!". milb.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Northrop, Milt (April 13, 1994). "Pilt Isn't A Stadium Stuck In 'Park' From Menu To Mascot's Pal, Bisons' Home Will Have Different Look". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Page 62". Democrat and Chronicle. July 9, 1992.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson, Dale (January 1, 1989). "Pop Music". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Over The Weekend". The Buffalo News. June 17, 1996.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Violanti, Anthony (May 30, 1997). "The Fest Lane Summer's Music Festivals Are Coming Fast and Furious". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sabres Talk". The Buffalo News. April 23, 1995.

- ^ "Entertainment/Music, Theater, Snow White". The Buffalo News. April 9, 1993.

- ^ "Stands of Times Through All The Changes, The Beach Boys Remain A Sign of Summer". The Buffalo News. August 24, 2001.

- ^ "Concert Calendar". Star-Gazette. July 5, 2001.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Beach Boys Come Bouncing Back". The Buffalo News. May 3, 1989.

- ^ "Bennett Pleasing In His Predictability". The Buffalo News. August 8, 1999.

- ^ Anderson, Dale (December 24, 1989). "1989: A Final Word From Our Critics". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Santella, Jim (August 30, 1995). "It's Hard To Be Blue When B.B. King and Friends Come to Town". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Over The Weekend". The Buffalo News. June 30, 1997.

- ^ "IL News and Notes". oursportscentral.com. International League. April 26, 2001.

- ^ Miers, Jeff (May 24, 2002). "Summer Smooch". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Gallivan, Seamus (June 3, 2012). "Kiss show is high-energy, sugary sweet". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Gallivan, Seamus (June 30, 2013). "Teens and tweens kiss the summer hello". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Sweeney, Joe (June 6, 2010). "This summer's officially Kissed". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Sweeney, Joe (June 4, 2009). "Pop music fans enjoy first kiss of summer". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Sweeney, Joe (June 5, 2011). "Time to say 'Hello' to summer music season". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Summer Concerts 2003". The Buffalo News. May 23, 2003.

- ^ "Counting Crows to play Dunn Tire Park". MiLB.com. May 18, 2007.

- ^ Schobert, Christopher (August 2, 2007). "A comfortable lineup of 90s nostalgia". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl VII with Sergeant Slaughter on August 27". MiLB.com. August 24, 2006.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl I". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl II - Field Of Screams". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl III - Canadian Carnage". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl IV - fridaynightSMASH". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ "V - Bang! Bang! Have a nice Day!". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl VI - Rochester Rumble". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl VII - Survival Of The Fittest". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl VIII". wrestlingdata.com.

- ^ Adler, Jim (June 19, 2011). "TNA Wrestling BaseBrawl House Show Results: Buffalo, New York (6/18/11)". wrestleheat.com.

- ^ Daly, Wayne (June 23, 2012). "TNA Results: Basebrawl Event – Buffalo, NY (6/22)". wrestling-news.net.

- ^ Chismar, Janet (July 17, 2012). "Buffalo Ready for Rock the Lakes". Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

- ^ Warner, Gene (November 30, 1988). "WINTERFEST TO RUN JAN. 26-FEB. 12 WITH THIS FOND WISH: LET IT SNOW". The Buffalo News. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ "WINTERFEST III". The Buffalo News. February 6, 1989. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ Nason, Geoff (May 4, 2016). "Goo Goo Dolls' Rzeznik Recalls Pilot Field During Interview On MLB Network". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "You Call This Art? Artist Jenny Holzer Wants To Talk To Real People About Important Things In A Direct Way". The Buffalo News. July 14, 1991.

- ^ Northrop, Milt (June 8, 1992). "Unlikely Stars Steal The Limelight In Shootout Bills Linebacker, Backup QBs Upstage NFL's Finest At Kelly Charity Carnival". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Liguori, Aaron J.; Habuda, Janice L. (June 14, 1993). "Kids Come Up Winners as Celebrities Pitch In And Make Stargaze '93 A Day To Remember". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 28, 1993). "A Special Night At Pilot Just Could Be A 'Natural'". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Archerd, Amy (August 24, 1994). "Chanel gets endorsement from Monroe". Variety.

- ^ Germain, David (August 28, 1993). "Buffalo honors The Natural". Montreal Gazette.

- ^ Cardinale, Anthony; Herbeck, Dan (July 25, 1996). "Curtain Rises On Empire State Games". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Reyes, Anthony (July 8, 2020). "National Buffalo Wing Festival pivots, becomes 'America's Greatest Chicken Wing Party' for 2020". wkbw.com. WKBW Buffalo.

- ^ Tokasz, Jay (September 21, 2012). "Franklin Graham follows father's footsteps to Buffalo event". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Nitro Circus You Got This Tour Buffalo". MiLB.com.

- ^ "Bills chemistry on display at Micah Hyde's Charity Softball Game". www.buffalobills.com.

- ^ Spencer, Crosby (September 9, 2020). "2020 Park Factors for the Seven New MLB Parks". RotoFanatic.

- ^ Galarneau, Andrew Z. (July 6, 2017). "Consumer's Pub at the Park replaces Pettibones at the stadium". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Farrell, Michael. "Eat and drink your way through nine innings like a Buffalonian". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "About Us | Union Pub in Buffalo, NY". unionpubbuffalo.

- ^ Reporter, Lance Lysowski News Sports. "Blue Jays briefs: Rowdy Tellez, 'homeless' Jays power past Rays". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Reporter, Mike Harrington News Sports. "Early returns make Sahlen Field a big-league bandbox for home runs". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "War Memorial Stadium Memorial at Coca-Cola Field -- Buffalo, NY, August 23, 2014". August 23, 2014.

- ^ Thompson, Carolyn (February 18, 2006). "Robert E. Rich Sr., at 92; invented nondairy topping". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Zremski, Jerry; Meyer, Brian (July 16, 2008). "Russert, Griffin names headed for public spaces Bills' stadium road; baseball park plaza". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Fetouh, Omar (August 17, 2012). "Jimmy Griffin statue unveiled at Coca Coca Field". news.wbfo.org. WBFO NPR.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Fetouh, Omar (March 21, 2013). "Bisons show off 'what's new' for 2013 season". WBFO.

- ^ Boutet, John (July 24, 2021). "'Baseball from the Beginning' Exhibit". MiLB.com. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Bisons to Retire Manto's no. 30 in August Ceremony". The Buffalo News. May 18, 2001.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 11, 2020). "Play ball: Buffalo is back in the majors as Blue Jays open series". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Directions -".

- ^ "Climate Charts: Buffalo, New York". climate-charts.com.

- General

- "2019 Buffalo Bisons Media Guide" (PDF). Buffalo Bisons. Minor League Baseball. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sahlen Field. |

- Official website

- Sahlen Field at Digital Ballparks

- Sahlen Field Ground Rules at MLB.com

| showEvents and tenants |

|---|

- Triple-A East ballparks

- 1988 establishments in New York (state)

- Baseball venues in New York (state)

- Buffalo Bisons (minor league)

- Buildings and structures in Buffalo, New York

- Defunct Major League Baseball venues

- Minor league baseball venues

- Music venues in New York (state)

- Populous (company) buildings

- Sports venues completed in 1988

- Sports venues in Buffalo, New York

- Sports venues in Erie County, New York

- Sports venues in New York (state)

- Toronto Blue Jays stadiums

- Tourist attractions in Buffalo, New York